It has been five years since Made in Lagos first graced our ears, yet it continues to sound startlingly fresh, as though time has not dared to leave its fingerprints on it.

By Abioye Damilare Samson

When historians and archivists reflect on the defining moments of 2020 in Nigeria, two tectonic events will always stand out: the devastating COVID-19 pandemic that kept the world confined indoors, and the #EndSARS protests that shook Nigeria to its core.

For music historians and cultural critics, these events formed part of the year’s backdrop, but the year carried a weight of a different order within the musical landscape. It was a year when Nigerian music expanded its reach and influence once again.

Albums returned to the centre of cultural conversation, with projects from heavyweight Afro-Pop acts like Burna Boy, Olamide, Fireboy, Davido, Tiwa Savage, Adekunle Gold, and more vying for space. Nigerian music and culture critic, Dami Ajayi, captured it best when he wrote, “The year 2020 will be remembered as the year that brought albums back into fashion, the first wave of its kind in about a decade since the zeitgeist shifted in favour of singles. The album, which had all but become an archival vestige, returned to the front burner in either the long play (LP) or extended play (EP) format.”

That was the exact current that framed the year. The world was slowed down, people were stuck at home, and for once, they had the time to sit and immerse themselves in full-length albums.

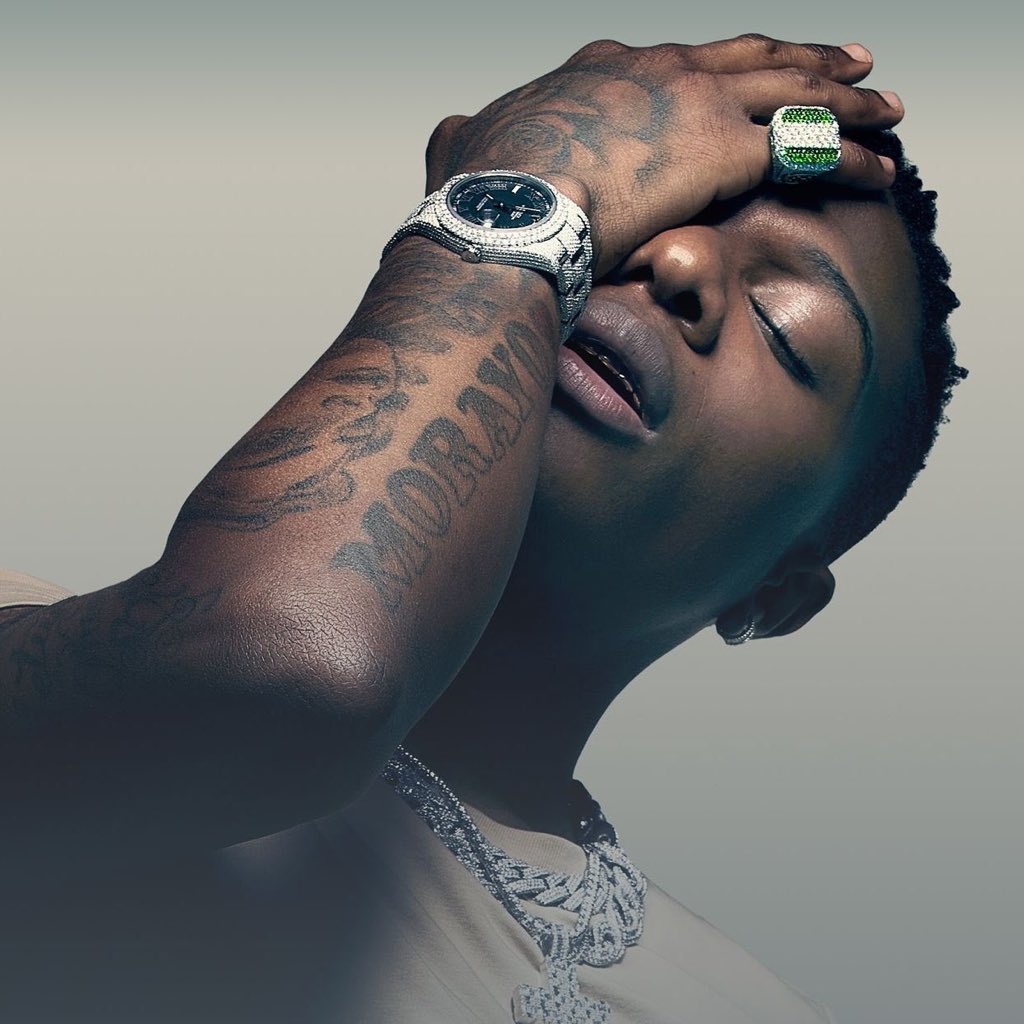

At the same time, the tension of the #EndSARS protest made people hungry for music that could either voice their rage or offer them escape. And it was in the middle of all that noise and silence that Wizkid stepped forward with the release of his fourth studio album, Made in Lagos. Before the album’s release, Wizkid had already spent years at the pinnacle of Afro-Pop, shaping the sound of a generation and amassing numerous awards and recognitions both at home and abroad.

His arrival at the peak of Afro-Pop with Made In Lagos was the culmination of a decade-long journey that began with Superstar—the dazzling debut that introduced him as the wonder kid of Nigerian pop, brimming with youthful melodies and citywide anthems.

Even prior to Superstar’s release, in June 2011, he had already made a significant statement with “Holla At Your Boy”, released on January 2, 2010. The smash hit single, which interpolates SE7EN’s 2009 “Girls” featuring Lil Kim, was an instant sensation, earning the then young, fast-rising Wizkid a nomination for ‘Best Pop Single’ at The Headies in 2011 (though he lost to Dr Sid’s ‘Pop Something’). Still, he walked away with the coveted Next Rated award that same year.

In those early years under Empire Mates Entertainment (EME) — the record label founded by the suave R&B singer Banky W, often credited with grooming some of Afro-Pop’s brightest stars — Wizkid was already cultivating a loyal following that would later grow into Wizkid FC, one of the most passionate fan bases in the world who have positioned themselves at the forefront of global stan culture — as the Swifties are to Taylor Swift, the ARMY to BTS, and the Beyhive to Beyoncé — fiercely protective, endlessly vocal, and deeply invested in every move their star makes.

His smooth delivery, effortless swagger, casual poise, and fashion elements—skinny jeans, colourful Supra sneakers, bold-print tees, and snapbacks—already shaped how young Nigerians wanted to sing, dress, and carry themselves. It was all there in the music, too.

In his irresistibly charming debut single, “Holla At Your Boy,” he boasted with a lightness that didn’t feel forced: “When you see me come around, I got you looking at me/ I don’t need to spend my cash, ‘cos my swag’s not hard to see”. The line was a statement of self-awareness from the young Ayodeji Ibrahim Balogun, who already knew he carried a kind of effortless aura.

But ultimately, he was a lover boy who prioritised his hedonistic desires more than anything else. The music video, directed by Patrick Elis, captured that magnetism perfectly by telling a simple, relatable story of young love. Every glance, playful gesture, and graceful move showcased his poise, making the story instantly familiar to anyone who has ever been in love in high school.

Still, Superstar was more than just a debut; it was the statement that crowned his ascendancy, a coronation of sorts, when a teenager dared to carve his name into the firmament of Nigerian pop, and announced, without reservation, the arrival of a future star. The choice of title still lingers with an almost mythic boldness. How does a 19-year-old decide to name his first album Superstar? Was it youthful audacity, or a prescient glimpse into the inevitability of his path?

In hindsight, the question borders on the surreal. For anyone else, it might have sounded like arrogance, even hubris—a reach too far without the artistry or ability to justify it. But for Wizkid, the talent was unmistakable and the confidence was impossible to ignore. Among the shining stars of Banky W’s EME roster—which included Skales, Niyola, and Shaydee—Wizkid stood out as a blazing talent, with magnetic vocals, effortless dexterity in delivery, and the “cool kid” image that hinted at the greatness to come.

If Superstar announced Wizkid’s arrival, then “Ojuelegba”, tucked into his sophomore album, Ayo, in 2014, completely changed the game for him and, by extension, for Nigerian music. Rooted in the grit and dreams of Lagos and brought to life by Legendury Beatz’s textured, pristine production, the track made him a household name across Africa and launched him into global consciousness.

Its remix with Skepta and Drake marked a decisive turning point as the first real footstep of Wizkid into international waters. Suddenly, he wasn’t just Nigeria’s boy wonder anymore; he had become a true global star, capable of commanding the ears of Lagos, London, and Toronto all at once. It was the very life he captured on the groovy, sax-laden opener “Jaiye Jaiye” with Femi Kuti: “Lagos today, London tomorrow, Oluwa lo se o, Omo jaiye jaiye.”

That moment inspired what came next. In 2017, Wizkid released his stateside debut project, Sounds From the Other Side, after signing a new record deal with RCA Records. It was his first deliberate attempt at a global crossover. The title said it all: music drawn from ‘the other side’, and specially designed to cross borders.

Sonically, the album leaned heavily on Western Pop, R&B, and Caribbean rhythms—particularly Dancehall—featuring collaborations with heavyweight international stars like Drake, Chris Brown, Trey Songz, Ty Dolla $ign, and Major Lazer. For Wizkid, the album was an avenue to expand his global reach, a fulfillment of the youthful ambition he declared on “No Lele” when he sang, “My music travels no visa”.

Beyond his personal ambitions, I consider the release of the album as the moment when Afro-Pop truly began to stretch its wings confidently on the global stage, and also when it began to redefine what international collaboration meant for Nigerian artistes in the modern pop landscape.

Here’s why: before then, Nigerians on the internet would go into a frenzy whenever a picture surfaced of a local artiste standing beside an international star. By hanging out with some of the biggest international stars, making music with them, and performing alongside them, Wizkid normalised these interactions and shifted the narrative from “Oh, a Nigerian artiste got featured!” to “A Nigerian artiste is collaborating at the highest level as a peer”.

Of course, this is not to say that Nigerian Pop artistes hadn’t collaborated with international acts before. Tuface—now known as 2Baba—had worked with artistes like Akon and T-Pain, D’banj had teamed up with Snoop Dogg and Kanye West, and Sound Sultan had featured Wyclef Jean. But I digressed. Even with all of these collaborations, such moments still felt extraordinary and almost unattainable for Nigerian artistes until Wizkid’s numerous collaborations with global stars made them feel more accessible.

Long before Made in Lagos finally dropped, the album had already taken on a life of its own. For nearly three years, it lingered in anticipation, promised but never delivered. Wizkid first teased it as far back as February 2018 with the hashtag #MadeInLagos, initially as an in-house EP for his independent label, Starboy Entertainment, and in the years that followed, he released a string of singles and hits, including “Manya”, “Nowo”, “Fever”, and “Joro”, among others.

Yet, the full project remained just out of reach until October 29, 2020. In the buildup to it all, 2019 saw the arrival of a surprise EP, Soundman Vol. 1—a project I consider, very importantly, as Wizkid’s foretaste to the local industry. Stylistically and sonically, Soundman Vol. 1 was, more than anything, a precursor to the palette and direction he would later refine to perfection on Made in Lagos.

By 2020, though, the air around Wizkid felt restless, expectant, almost as if people were waiting to see what version of him would emerge next. This was primarily because of the shifting dynamics among the “big three” of Nigerian Pop: Burna Boy had staked his claim with the career-defining African Giant, the project that helped him earn Grammy attention, while Davido was doubling down on his hit-making formula by riding the reigning Pon Pon sound wave that defined much of the scene.

On the other hand, Wizkid’s last major outing had left some wondering if he had tilted too far toward global compromise, with conversations even emerging about whether he had reached a plateau in his artistry or if his music had begun to lack substance during that period.

Amidst all the speculation, scrutiny, and the rise of a new generation of artistes—including Fireboy DML, Rema, and Omah Lay—who were beginning to be compared to him, Wizkid was never in danger of fading; yet the question that lingered was: what direction would he take next?

The repeated postponements of Made in Lagos only heightened the conversation. At first, he shared July 16 as the release date, even teasing on Instagram that it was the best album he had ever made. However, the album didn’t drop at that time. He later announced October 15 as the official release date, only to push it back again, this time in solidarity with the nationwide demonstrations against police brutality.

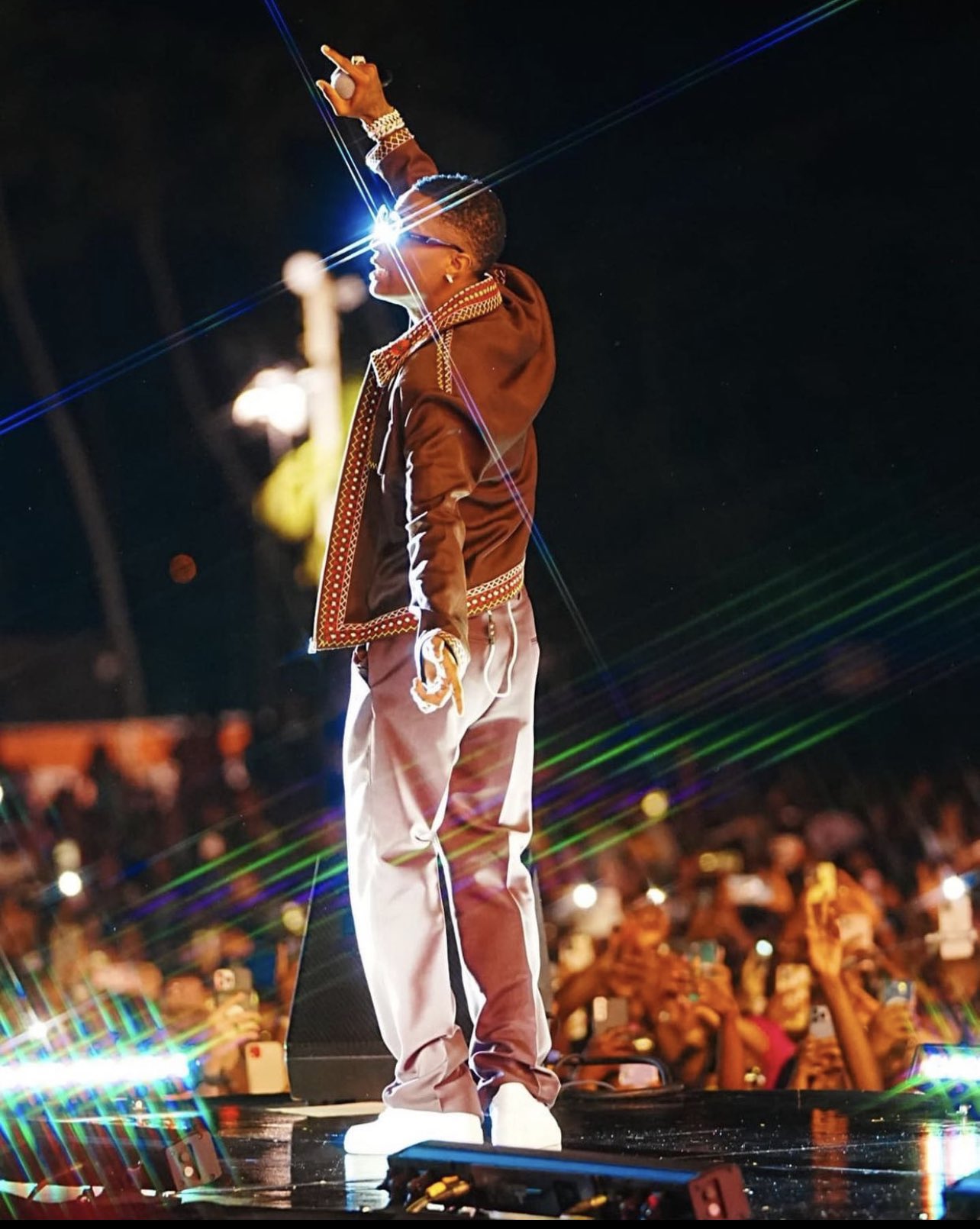

In the thick of these delays, Nigeria was shaken by the October 20 massacre of EndSARS protesters at the Lekki Toll Gate. The country’s mood was raw, grief-stricken, and weighed down by a sense of disillusionment. It was against this backdrop that, on October 29, Made in Lagos finally arrived.

It feels deliberate that Wizkid begins Made in Lagos with “Reckless”. Almost as if he had been listening to the chatter about a plateau in his artistry, And so, after the gentle crawl of keys and the roll of hi-hats and bass drum kicks, he sings with utmost composure: “Dem inna, inna, inna, inna, inna (No lie)/ I know say dem go pray on my downfall / I’m still a winner, winner, winner, winner, winner (Spiritual)”.

The statement is clear: the crown is not up for contest. But Wizkid has never been one to dwell in combat; even here, the rebuttal quickly dissolves into melody to remind that his allure and influence remain intact in the first verse, “Melody sweet but you know sey man so G’d up, yeah/ That’s why the girls dem follow the leader,” he croons.

The bounce on “Ginger” with Burna Boy immediately locks in the groove, with the two Afro-Pop giants delivering flawless chemistry. Yet, the real allure of the song comes toward the end, where Burna Boy’s modulation heightens the track’s intensity. Perhaps, the most striking quality of Made in Lagos is that debauchery and sensualism are on full display, balanced with musicality and melody.

The results are just as compelling when Wizkid pairs with other kindred spirits: the mid-tempo collaboration with Skepta on “Longtime”—which recalls the energy of their earlier hit “Energy (Star Far Away)”—the mellow R&B “Piece of Me” with Ella Mai; the Reggae-infused “Smile” with H.E.R., the hypnotic “Essence” with Tems, and even on “True Love” featuring Tay Iwar and Projexx, Wizkid finds the perfect intersection of poignant melody, sensuality, and flowery songwriting.

On “True Love”, for instance, the title suggests a pure, innocent romance, but the lyrics tell a different story. Wizkid croons, “Inside, she control me/ She dey tell me, ‘Baby, buss it, don’t you fool me’/ Hot fuck every day, she dey consume it”, a line that captures the fluid blend of desire, intimacy, and musical sophistication that runs through the album.

Even when he sings alone on tracks like “Mighty Wine”, “No Stress”, “Sweet One”, and “Gyrate”, the current that runs through it all suggests that hedonism is the most dominant theme of the album.

While much of the album revels in pleasure, it also pauses to honour reflection and celebration, notably on “Grace” and the Damian Marley collaboration “Blessed”, where both artistes channel the Rasta ethos of appreciating the simple joys of life. It’s evident in Marley’s lyrics when he sings: “Let’s celebrate life/ Kick back and take five/ And give thanks to the source that create life/ To see a sun set or see a sun rise/ And see my son born with these same eyes/ To see my son smile, brighten every grey sky”. Wizkid demonstrates a similar philosophy, embracing the art of living in the moment. On the third verse of “Blessed,” he sings: “See, I don’t wanna talk about the things wey go really really make me down tonight”.

Yet, what makes “Blessed” one of the album’s most significant tracks is its opening, a sound collage of market chatter and a woman screaming, “Cold mineral, Cold Pure Water”, which captures a brief but vivid snapshot of everyday Lagos life that anyone who has walked through the city’s markets and traffic will immediately recognise.

To be ‘Made in Lagos’ is, in part, to immerse oneself in these everyday sounds and textures of the city, and this intro distils something fundamental about Lagos street culture in a striking, immediate way.

But here lies the album’s central paradox: despite its symbolic, homage-driven title, Made in Lagos was created far from Lagos itself. Recorded largely outside Nigeria, with predominantly behind-the-scenes collaborators — including UK-based lead producer, P2J, and Los Angeles–based audio engineer, Leandro Hidalgo — the album’s sonic palette leans more toward Caribbean R&B than traditional Afrobeats and contains almost no direct commentary on Lagos’s actual daily struggles: the grinding traffic, the power cuts, and the economic inequality that shapes life in the city nor does it explicitly chronicle Wizkid’s journey from Ojuelegba to global superstardom.

Even so, this isn’t necessarily a flaw—Wizkid has earned the right to his own mythology—but the title does complicate how we think about the album as a Lagos story.

Ojuelegba, in Surulere, where Wizkid—then known as Lil Prinz and starting out as a rapper—grew up, is a bustling creative hub on the Lagos mainland where he had to hustle to make it out and navigate the city’s challenges while shaping his artistry. That backdrop is essential to understanding his relationship with Lagos and, by extension, the album’s meaning, which is not a documentary of the city’s present-day realities, but rather an expression of how deeply Lagos has shaped him, even as he has moved beyond its physical borders.

Critics often argue that Made in Lagos was crafted solely for Western ears rather than for Lagos (read: Nigerian) listeners, due to its mid-tempo grooves, R&B sheen, and its prioritisation of mood over the high-energy percussion that dominates Nigerian clubs.

However, for all its polished production and global ambitions, the album subtly keeps Lagos at its centre, embedding its homage in linguistic choices, sonic gestures, and cultural references rather than explicit social commentary or direct depictions of Lagos street life.

This approach shows up most clearly in the album’s choice of artistes and linguistic references. Wizkid balances local and international voices—Tems, Burna Boy, and Terri alongside Ella Mai, Skepta, Tay Iwar, and H.E.R.—in a way that anchors Made in Lagos in a global conversation while retaining its distinctly Lagos heartbeat.

Even in tracks that explore love, desire, or celebration, there’s a vivid sense of place and lived experience: the cultural references and the everyday interactions that together create a portrait of the city filtered through the vision of one of its most prominent musical voices. On “Ginger” with Burna Boy, for instance, slang does much of the heavy lifting. To “ginger” someone in Lagos parlance is to stir them up, to energise or excite. Lines like “Ma ko o je bi jollof” casually nod to the city’s culinary pride—Nigerian jollof rice—while playful slang such as “kponono” grounds the song in the earthy, unfiltered language of Lagos streets. These linguistic textures root the music—and by extension, the album itself—in the pulse of everyday Lagos life, even as its sound moves fluidly onto the global stage.

Alongside the well-curated collaborations, the album shines in its futuristic production, thanks in large part to P2J, whose lush arrangements and masterful layering of sounds give the tracks a signature depth that elevates the listening experience. The luxurious textures of sound and rich instrumentation—especially the saxophone, which appears throughout the album—add warmth and richness to the tracks. It’s no wonder listeners were eager for more, which helped prompt the release of the deluxe edition the following year.

Rightfully so, Made in Lagos has been widely described as one of the most impactful Afro-Pop albums of all time, securing its place in the canon of contemporary Afro-Pop classics and shaping the framework for what a conceptual album could look like within the genre.

Beyond its artistic achievements, its commercial and cultural afterlife has been equally remarkable, as it continues to garner certifications, streams, and acclaim year after year. Notably, the album also garnered global recognition, earning Grammy nominations for “Essence” featuring Tems in the Best Global Music Performance category in 2022, as well as for Made in Lagos: Deluxe Edition in the Best Global Music Album category.

It has been five years since Made in Lagos first graced our ears, yet it continues to sound startlingly fresh, as though time has not dared to leave its fingerprints on it. As Pablo Picasso put it, “The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls”.

With Made in Lagos, Wizkid did precisely that by ascending into a god-mode tier of artistry to conjure a sonic refuge that invites listeners to slip into the soothing cadence of its sensual, melodically rich songs and find rhythm, escape, and light amid one of the darkest moments in Nigeria’s recent history, as well as the global unrest that marked the period of its release.

Abioye Damilare Samson is a music journalist and culture writer focused on the African entertainment industry. His works have appeared in Afrocritik, Republic NG, NATIVE Mag, Culture Custodian, 49th Street, and more. Connect with him on Twitter and IG: @Dreyschronicle