Adunni: Ogidan Binrin is a reminder that even the most righteous revolutions can falter when the narrative weapons they wield are blunt.

By Joseph Jonathan

In 1929, thousands of Igbo and Ibibio women rose up against colonial tax impositions in what history remembers as the Aba Women’s War — one of the earliest recorded anti-colonial revolts in Africa led entirely by women. Their courage not only defied the British administration but also challenged the patriarchal systems that had long silenced them.

Almost a century later, Adunni: Ogidan Binrin revisits that same spirit of resistance — though in a fictional Yoruba town — where women once again rise to confront the intertwined powers of patriarchy and colonial exploitation.

In Adunni: Ogidan Binrin, director, Yemi Amodu, takes on a familiar but potent narrative canvas: the struggle of women against tyranny, and the eternal tension between tradition, colonial complicity, and the quest for justice.

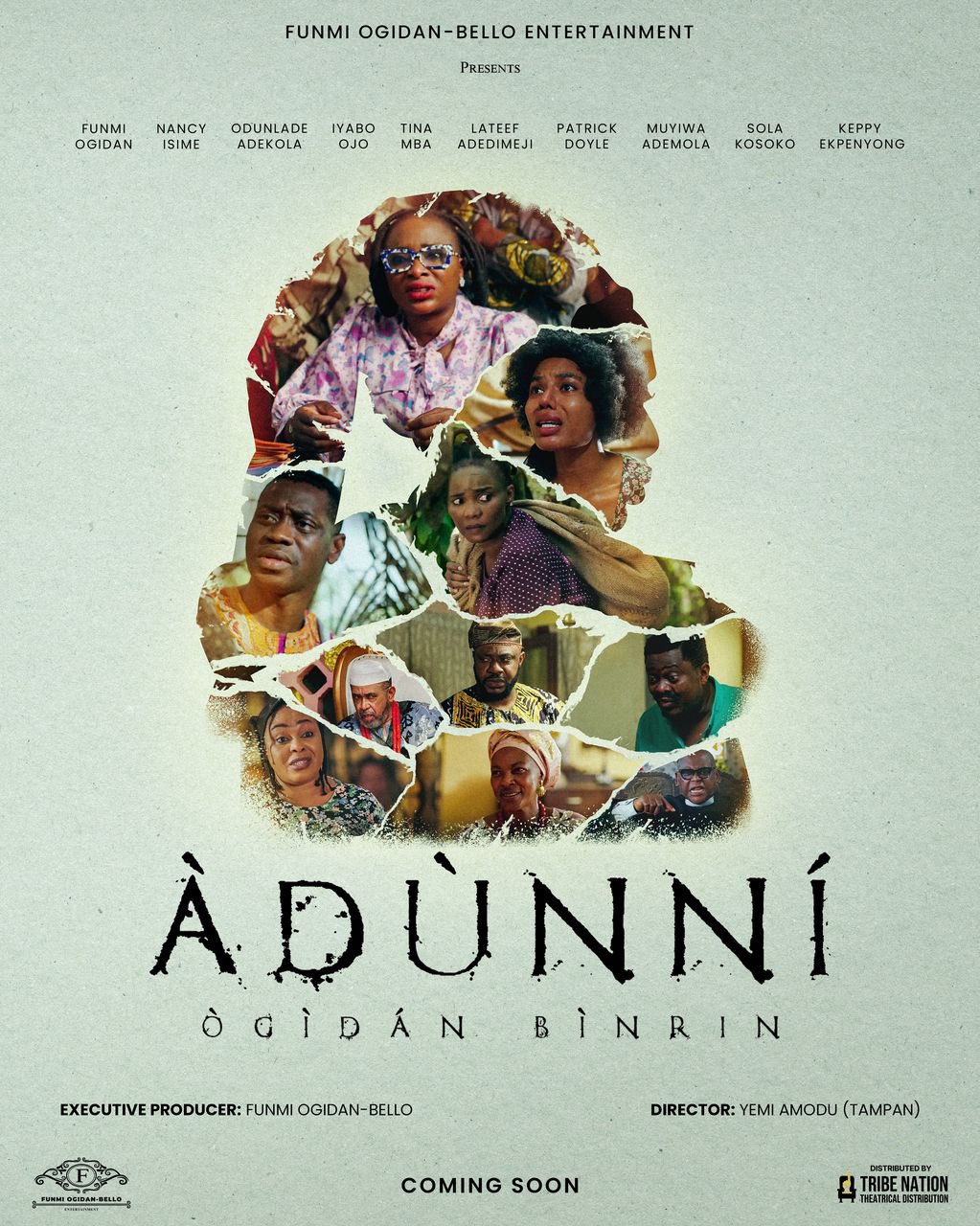

Set in a pre-independence Yoruba town, the film follows Adunni (Funmi Ogidan Bello), a fearless barrister whose defiance places her in direct opposition to a despotic monarch, Oba Adedamola (Patrick Doyle). With his power fortified by the District Officer—a symbol of colonial machinery—the Oba plunders his people’s wealth, exploiting their labour and trust. When Adunni, alongside Romoke (Nancy Isime) and Abegbe (Shola Kosoko), leads the women of the community in revolt, the film positions itself as a story of awakening, courage, and moral clarity.

It is an ambitious premise, one that promises to weave gender politics, colonial critique, and moral reckoning into a tapestry of pre-independence Nigeria. Yet, somewhere between its intentions and its execution, Adunni: Ogidan Binrin loses its footing. The result is a film whose thematic richness is undermined by clumsy storytelling, uneven performances, and a tone that wavers between earnest drama and unintentional parody.

The central story of Adunni: Ogidan Binrin hinges on confrontation: between the governed and the governing, between women’s voices and patriarchal silencing, between justice and fear. However, the film’s storytelling too often feels mechanical, as though events unfold not from organic motivation but from narrative convenience.

When the women’s revolt hinges on obtaining incriminating evidence against the Oba and the District Officer, the plot conveniently supplies it through one of the Oba’s chiefs—a man who, for no discernible reason, betrays the ruler he has loyally served. What drives his sudden moral epiphany? Was it disillusionment, guilt, or a personal vendetta? The film never tells us. Instead, it moves briskly past the question, content to let convenience masquerade as character development.

This lack of narrative logic becomes a recurring flaw. Characters appear and disappear without consequence. Conflicts are introduced with great fanfare only to be resolved hastily or forgotten altogether. The result is a film that feels like it knows what it wants to say but not how to say it in a way that feels earned or emotionally resonant.

With a cast boasting industry heavyweights—Patrick Doyle, Nancy Isime, Shola Kosoko, Lateef Adedimeji, Odunlade Adekola, Keppy Ekpenyong, Iyabo Ojo, Tina Mba, Muyiwa Ademola, Jide Kosoko, Afeez Oyetoro, and Funmi Ogidan Bello, Adunni: Ogidan Binrin should have been a showcase of compelling performances. Instead, the ensemble delivers work that ranges from flat to overwrought.

Patrick Doyle’s Oba Adedamola has the gravitas of a tyrant but not the menace; his authority feels declamatory rather than lived-in. Funmi Ogidan Bello, as Adunni, embodies the spirit of defiance but struggles against dialogue that often reduces her to slogans rather than flesh-and-blood conviction. Nancy Isime and Shola Kosoko provide flashes of presence, but even their performances are weighed down by melodrama that replaces subtlety with noise.

In fairness, much of this is not the actors’ fault. The writing gives them little to inhabit beyond archetypes. Adunni is “the brave one”. The Oba is “the corrupt ruler”. The District Officer is “the colonial puppet”. These archetypes could have worked had they been infused with texture, contradiction, or surprise. Instead, they remain one-dimensional, denying the audience the complexity that stories about resistance and power so urgently require.

And then there’s the matter of the District Officer’s accent—perhaps one of the worst colonial affectations in recent Nollywood memory. It distracts from every scene he’s in, flattening the tension that should have underscored his exchanges with the Oba.

There is no mistaking what Adunni: Ogidan Binrin wants to say. It taps into universal themes of resistance and resilience, echoing the spirit of women-led revolutions across history—from the Aba Women’s War of 1929 to the countless, often unsung, acts of defiance that shaped postcolonial consciousness. Adunni’s rebellion becomes a symbol for every struggle against systemic injustice, every demand for dignity in a world determined to withhold it.

Yet, even though the film sometimes leans into being overly didactic in passing its message—choosing exposition over subtext, speech over silence—it still manages to remind us that defiance comes at a cost. What it lacks in narrative finesse, it makes up for, at moments, with sincerity. But sincerity alone does not sustain a film. Without cinematic discipline—without the emotional logic and structural precision that turns the theme into art—Adunni: Ogidan Binrin remains a noble attempt trapped in its own ambition.

Visually, the film attempts to recreate pre-independence Yoruba society with commendable production design—costumes, set pieces, and scenes that evoke a sense of time and place. Yet, the cinematography feels inconsistent, and the editing lacks rhythm, often breaking the film’s emotional continuity. The pacing suffers as a result, with scenes dragging longer than necessary and transitions feeling abrupt.

There’s also a missed opportunity in how the film engages Yoruba cosmology and oral tradition. For a story set within such a rich cultural context, Adunni: Ogidan Binrin could have drawn from the poetry, folklore, and idiomatic texture of Yoruba storytelling to deepen its themes. Instead, it occasionally feels detached from the cultural soil it claims to till.

Adunni: Ogidan Binrin is a film that wants to roar but only manages a murmur. Its themes of courage and collective resistance are timely and timeless, but its execution dulls the power of its message. What should have been a stirring exploration of women’s agency in a corrupt patriarchal system becomes a case study in how weak storytelling can betray strong intentions.

Still, the film’s heart is in the right place. There is passion in its making and purpose in its message. But passion without precision is seldom enough. Adunni: Ogidan Binrin is a reminder that even the most righteous revolutions can falter when the narrative weapons they wield are blunt.

Rating: 2/5

*Adunni: Ogidan Binrin was released in Nigerian cinemas in July 2025 and screened at the Abuja International Film Festival (AIFF) 2025.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big.