Concentration happens on different levels. The human brain is on a diverse spectrum, and people understand things in different ways. The diversity of the ways in which humans comprehend symbols and phenomena is precisely the reason why some people are more aurally or visually attuned.

By Chimezie Chika

A Pleasure Principle

Between primary school and university, I was asked many times why I read books that weren’t part of my school work, to which I replied that I simply enjoyed those books and that there was surely a lot more to learn outside my school work—a response which my interrogators scoffed at.

As far as they were concerned, reading had to be a means to an end, and that end must be of some economic significance, however immediate or long-term. And for them, reading for pleasure or enjoyment didn’t qualify. It seems to me that there has always been an erroneous notion — from particularly that uppity generation we call baby boomers to the evidently less-intellectually attuned sections of recent generations — that pleasure and intellect cannot be merged and that both are necessarily divorced.

Sad as it is that this overly utilitarian state of mind is the dominant attitude towards reading in Nigeria; it has been proven that enjoying what one is reading is an immensely better way to approach reading. It has a number of enduring benefits, chief of which is improved cognitive abilities. The decline of reading in this country is directly traceable to the perception of reading as a complicated, elaborate, static process—a chore, more or less—connected to the end product of a rigid, preset curriculum.

The dominant attitude towards reading here is that reading is simply something you do to get ahead, not something you enjoy. It is why a vast majority of people in this country only associate reading with exams or as an effort towards some form of career advancement, after which the exertion of reading is promptly abandoned for more pleasurable pursuits (whatever those are).

In all honesty, the prevailing pleasures of today’s non-reading public likely have something or other to do with the internet and social media, where a deluge of visual information is ever in competition for our malleable attention, the repetition of which will subsequently proceed to numb and fry the brains. If we agree that such people, with their misinformed biases around recreational reading, must be convinced that reading can be treated the same way they treat their favourite content creators, comedy reels, and podcasts (which can be quite stimulating), what do we suppose is the best way to do that?

The literary community in Nigeria and all over the world has repeatedly complained about the decline of reading (and it’s important to note that they do not mean the obligatory reading associated with school work), and the diagnoses habitually point to the rise of the internet, which, as I always maintain, is not entirely bad in itself.

We cannot reverse the internet; in short, it has become integral to the locomotion of our world. We know that the internet has exerted the biggest tangible change on how we have lived these past three decades; it has introduced new words, adjusted the definition of things, and permanently altered the way in which things—from business to journalism—were previously done.

These should not surprise us, even if we double down to maintain the status quo in certain areas for moral reasons, knowing that the most prominent attribute of technology is its ability to enact almost immediate change, whether for good or bad.

Considering how much the intellectual world has taken to the internet, the one way we can continue to deal with information technology is to recreate it in our own image, to harness it in whatever way possible (which is already being done with online magazines, substacks, intellectual podcasts, the endless knowledge banks of YouTube, etc).

In an age of unstable attention, it shouldn’t be news that the best way to keep the wheel of literature running at this time is to continue to find ways to adjust literature to the most utilitarian technologies available, especially since literature itself should first yield pleasure and entertainment. The main question we should ask today should be how best to turn some of that perennial social media feed addiction into one sustained enough to finish a 200-page book.

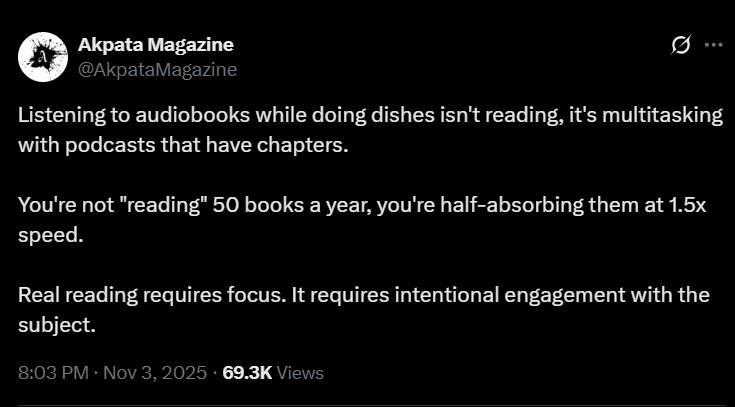

How surprising it is then, that Akpata Magazine, a young literary journal, would make a tweet on X disparaging readers of audiobooks. The exact tweet goes:

In simple terms, the tweet claims people who multitask with audiobooks are neither reading nor entirely digesting whatever they are listening to. The poster described the activity as listening to “podcasts that have chapters”. In truth, the very idea of audiobooks as “not reading”—yes, the grammar shows you are listening to it, not necessarily reading it—is rational at first glance, as is the idea that multitasking with it probably impedes full engagement with the book.

But herein lies the fault of such an argument: the same things can be said for hard copies, too. You can lose concentration if you multitask; your comprehension of the text may not be optimal, even if you stare down every word on the page.

Concentration happens on different levels. The human brain is on a diverse spectrum, and people understand things in different ways. The diversity of how humans comprehend symbols and phenomena is precisely the reason why some people are more aurally or visually attuned. A synaesthetic brain, for instance, will get to the objective understanding of a thing differently compared to a non-autistic brain. In a world with a better understanding of the phenomenon of neurodivergence, Akpata Magazine’s tweet is unnuanced.

Yet, the basic considerations are here: is listening to audiobooks reading? Does reading mean anything other than conventionally staring at or reading from the page while the brain interprets? If we can understand the semantics of reading, both beyond and within this age, then we might come to an illumination.

What Is Reading?

The term reading came with the development of writing. In evolutionary terms, reading was one of the latter skills that our species developed. Before that, the visual and auditory senses were primal in how humans told, understood stories, and interacted with the phenomena of knowledge in their environment. The Oxford Dictionary conventionally defines reading as “the activity or skill of looking at and comprehending the meaning of written or printed matter by interpreting the characters or symbols of which it is composed”. The definition from the Cambridge Dictionary—“the skill or activity of getting information from books”—is more encompassing.

Both lexicons agree that reading is a cognitive process: that is, it involves the spontaneous or conscious interpretation of word or morphemic meaning. To do this, all the human senses must come into play.

Conventional reading is still majorly a combination of visual, oral, and auditory exercises heavily subsidised by the human brain. This composite cognitive process will affect reading if one or the other is not there, granted that audio reading is a double-layered process. Active reading is not exclusive to hard copies alone; no matter how you are reading, you are also seeing, hearing, and feeling. This is why we reread—which can even be an unconscious activity: we have a natural propensity to go over words, sentences, passages more than once—to achieve better cognition.

Is reading a hard copy or listening to audiobooks mutually exclusive? How would we comprehend a book that we both read in its hard copy and listened to its audiobook? I would hazard that the understanding would only be about the process—especially in terms of the languages—of getting to that understanding rather than the understanding itself, since the text is still the same, whether we are looking at the written words or interpreting them from hearing.

Nothing new here, really, if we get down to it. Akpata Magazine’s charge, when all is said and done, is the same reflexes that typify human responses to newness. There is often a kickback when a new order—whether niche or mainstream—enters the fray; the human tendency to erect guardrails for kicks in.

What Is an Ideal Medium to Consume Literature?

There are two questions here: what is the right way to read, and what is the right medium for reading? On the first question, we cannot talk about the right way to read—if there is indeed a right way—if we do not first consider the oldest way in which storytelling happens. Since literature is, at its core, about storytelling or communication of ideas, how best can a story be told, or how best can an idea be communicated?

Oral storytelling is humanity’s oldest way of communicating ideas. In that process, an individual tells a story to a group while the group listens. This verbal-to-aural communication would prevail until the invention of writing, a form that had greater reach, though not necessarily better than orality in cognitive quality. This was a departure from the old order and involved direct visual-brain communication. Even while reading, some people still prefer the old way of reading aloud, though this slightly alters the process into a visual-verbal-aural one.

The last process is why audiobooks make sense, because it follows the same pattern to comprehension: the cognitive process of reading is achieved by hearing someone else read a book aloud. This makes the audiobook a direct descendant of oral storytelling; it is, therefore, in that sense, the oldest form of storytelling. The link between auditory ability and comprehension/retention is evidenced not only in age-old oral traditions passed down for millennia, but has also been studied in clinical psychology.

The one great attribute of the invention of the hard copy book was that it made the dissemination of information easier, and it can be imbibed over a length of time, as opposed to the spontaneous, location-limited immediacy of oral storytelling. It does seem that the audiobook was invented to combine the best aspects of writing and orality (the main reason, when it gained ascendancy in the 1930s, was to allow the visually impaired and disabled WWI veterans to read—and this alone justifies the multiple accusation of the Akpata Magazine tweet as ableist, though they said, in an essay defending their stance, that the tweet does not constitute an attack the disabled: “We suggested that different modes of engagement produce different kinds of understanding”; the evidence of the tweet itself says otherwise). Audiobooks’ earliest iterations, such as phonographic recordings of stories, show that humanity would always carry its appetite for orally told narratives into any new technology. Social media itself is an example of the visual-oral-auditory paradigm.

Towards Pointlessness

One of the long-running risks of the human tendency for innovations is that innovations can often quickly become the dominant mode of expression or way of doing things, due perhaps to increased convenience (which is what innovation does). While the degree of the general acceptance of new technologies may vary according to utility, it is notable that such technologies are not islands in themselves (indeed, capitalist consumerism promotes variety and technological duplicities).

Audiobooks are only one way to read, and so are hard copies, digital books, etc. Whichever one chooses, according to one’s strength and capacities at any given time, the reading experience is not diminished by the choice of media. In each one, one could seek to be faster or slower, sporadic or consistent, invested or detached, according to one’s needs. This cognitive motility is why literature is better served by innovation, for it adapts itself to suit all kinds of needs.

The reading debate started by Akpata Magazine is one of those conversations over which one is tempted to ask: to what end? What does it contribute towards a better understanding of literature? We consume literature for enjoyment and edification, with all the sensory and mental responses that make it possible.

For this reason, literature is an experience. The channels through which we experience literature are ever-evolving because humanity wants to make reading even more of an experience. We should allow readers the opportunity to experience literature—even as something that helps you relax while doing the dishes. (In that Akpata Magazine’s tweet, if we replace ‘audiobook’ with ‘music’, no one would have complained. Why then should literature be less of an experience than music?)

The novelist, Chika Unigwe, captures it well in her response to Akpata Magazine’s tweet: Medium doesn’t matter, as long as the thing is done. What matters is that one has absorbed, comprehended, and engaged with literature; the means by which that end is achieved does not matter.

It is pointless to argue about the reading media or the ways people read (hell, some of us juggle through more than one book at the same time); such an argument does not add anything to the fount of human knowledge. If reading is about absorption, who said that there is only one way to thoroughly absorb literature?

Chimezie Chika is a staff writer at Afrocritik. His short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Weganda Review, The Republic, The Iowa Review, Terrain.org, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Fahmidan Journal, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, and Channel Magazine. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture, history, to art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on X @chimeziechika1