“We see ourselves as participants in a rich and evolving history set on continuing to firmly articulate Ghana and Africa to the world. We are our stories, in the same way that if you don’t see where you’ve come from, you have no context for where you can go.” — Nana Adwoa Frimpong

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

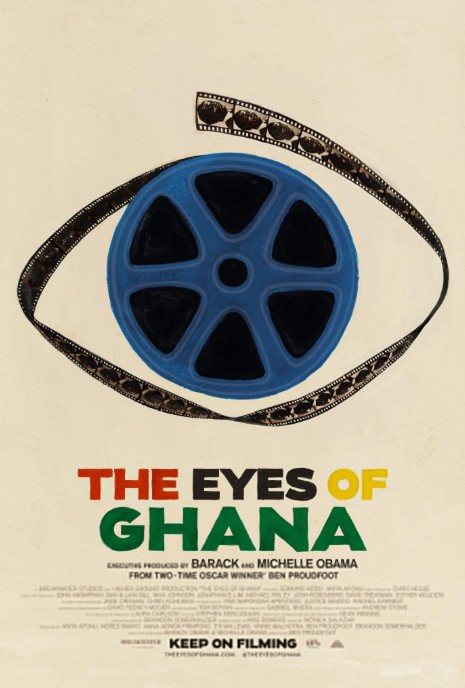

For such a storied continent, far too much African history has been lost, sometimes through deliberate political erasure, sometimes through a weak culture of archiving and preservation. The story of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first prime minister and president, who led his country to become the first Sub-Saharan country to gain independence from European colonisation, has suffered some erasure on both counts. After the nationalist leader was deposed in a 1966 military coup, many of the materials relating to him were destroyed, lost or seized. The Eyes of Ghana (2025), a documentary directed by two-time Oscar winner, Ben Proudfoot, seeks to help correct that.

The Eyes of Ghana follows 90-year-old Chris Hesse, a Ghanaian filmmaker, who was once Kwame Nkrumah’s personal cameraman. Hesse has been working to restore and digitise over one thousand reels of historical film footage that were thought to have been destroyed, but which he had safely stored away in London. The documentary records these efforts while also exploring Nkrumah’s legacy and Ghana’s political and cinematic history.

Nana Adwoa Frimpong, a Ghanaian-Canadian filmmaker, Vice President (Partnerships & Impact) of Proudfoot’s Breakwater Studios, and a producer on The Eyes of Ghana, grew up hearing about Nkrumah from her family, but not in school. So, it is no surprise that very few people are familiar with this crucial chapter of African history.

“There is a similar reaction we get every time we pitch this film to people, and it’s one of shock, awe, and a feeling of ‘How do I not know this history?’” she tells Afrocritik. “Our film is not the seminal Nkrumah legacy piece—although that film should very much be made—but it is a rewriting of a wrong by way of reintroduction through storytelling. Nkrumah knew that film had the power to change perception, signify meaning, and tell an African story that was celebratory and vast.”

In this interview with Afrocritik during the 2025 African Diaspora International Film Festival (ADIFF), Nana Adwoa Frimpong talks about the responsibility of cinema as a tool for historical preservation, the decision to centre Chris Hesse in the documentary’s narrative, and the broader impact ambitions of The Eyes of Ghana.

As festival season draws to a close, how does it feel to have Eyes of Ghana enjoy such a successful run on the festival circuit?

It is an incredible feeling. We are extremely grateful to the various programmers and audience members who have seen the film and told other people to watch it.

Documentary filmmaking often pulls filmmakers towards stories outside their immediate orbit. How did your team come across Chris Hesse, and what drew you to his story?

A few years back, Ben was in Ghana making another film called If You Have for UNICEF’s 75th anniversary. One day, while on production, the crew drove past the Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum. For those who have not seen it, it’s quite unique in that it’s made of stone and slopes downwards. If you have no context for it, it’s something you’d take note of. It was upon inquiring as to who Nkrumah was that Ben learned of his power and legacy.

It just so happened that our co-producer, Justice Baidoo, was in the car, and knows Chris Hesse, who in his youth had served as Nkrumah’s personal cinematographer. We were drawn to the story because in the west, Kwame Nkrumah’s legacy is largely unknown, and Chris Hesse’s legacy, once known, is one of profound importance, too. We knew that we cared about the story, and so hoped that once heard, others would too.

Did your perspective on cinema’s responsibility in reviving and preserving history and truth change or expand while making The Eyes of Ghana?

Expanded. Most definitely. Before studying film in earnest, I had no language for its power. From an early age, I knew that I loved watching film and television, but my vocabulary mostly began and ended at “that was good” or “that wasn’t very good at all.” I intuitively knew when I would bump up against something in the storytelling, or felt like another element of the production did not fit my taste, but I did not spend much time dwelling on much beyond that.

When I took my first film class at the University of Toronto, my whole world opened up because it was the first time I realised that film was more than just a medium for entertainment, but a pathway to understanding and a means for truth-telling and excavation. When done right, we see ourselves in the storytellers that occupy our screen, and we are grateful for the slices of humanity they leave with us.

In the case of this film, a new sliver of cruciality made itself present, and that was one of preservation and history keeping. That is to say, cinema’s responsibility to a country and a people, particularly a people that have not had their histories preserved and disseminated on a global scale.

Many have come before for us in terms of articulating the importance of Ghana to the world, but it’s not enough to stop here. We see ourselves as participants in a rich and evolving history set on continuing to firmly articulate Ghana and Africa to the world. We are our stories, in the same way that if you don’t see where you’ve come from, you have no context for where you can go.

Your key subjects have deep ties to cinema, and that connection shapes the documentary into a kind of homage to cinema. Was this always your intention, or was there a turning point in the process where you realised that would be the most resonant angle?

We knew that cinema’s role in this story was important and that it would be the foundation for all things. We weren’t always clear on how much of Nkrumah’s legacy to include, though. We knew that for many of our audience, this would be the first time they’d even heard his name and that in order to do a good enough job of drawing people in, we had to explain enough of his legacy so that you felt like an active participant in Chris Hesse’s fight.

Chris Hesse was also our North Star. We leaned on his narrative to tell the story and believed that sticking to his perspective would be our ultimate guide to understanding what story we were really telling. The entire process took a lot of time, and the patience and skill of our editor, Mónica Salazar, made it so that we were able to strike the right balance between legacy, cultural relevance, and Chris’ love of cinema.

How did having filmmakers as your subjects influence your process and, ultimately, the goals you set for the documentary?

On the storytelling side, we wanted to honour Chris Hesse’s story. We wanted to make sure he recognised his life in the film, and that the parts that were included gave the proper context for the story he wanted to tell. On the technical side, it meant having a dedicated team that was committed to the same level of excellence.

We wanted to elevate the film in every way possible. For the ending sequence, for example, we shot that on 65 mm celluloid using an IMAX camera. Fellow producer and director of photography, Brandon Somerhalder, was incredibly focused on making this a reality, and I think the end product is a cinematic revelation that honours our storytellers.

We also had the pleasure of working with Kris Bowers and his team at Et. Al Studios, Max, Sahil, and Peter—who were vision-forward in their approach. Kris was deliberate with the instrumentation that he used, infusing culturally specific elements like the atenteben, a Ghanaian flute, to evoke the mood and a true sense of story. We also scored the film at Abbey Road Studios with the Chineke! Orchestra, a historically Black and ethnically diverse group based in the UK, again, all with the intention of working with the best in the world to honour Chris.

The Eyes of Ghana revisits Kwame Nkrumah’s image as a revolutionary but doesn’t shy away from the harsher realities of his leadership, particularly his authoritarianism in his later years. Why was it important for you to feature that in the documentary rather than lean solely into the hero narrative?

As documentary filmmakers, the truth is what you have. In order to tell a fully dimensional story, we needed to tell the good and “bad”, even if that meant highlighting a facet of Nkrumah that makes people uncomfortable. We never saw it as our responsibility to tell the audience what they should believe about Kwame Nkrumah. As Chris Hesse says in the film, he filmed it all so that we can be the judge.

I think we can only ever truly get to the heart of any matter if we’re willing to pose the uncomfortable questions that simultaneously cut through our most precious, perhaps even sacred truths. You can believe that Kwame Nkrumah is the greatest leader of all time and still have qualms about how he used Ghana’s resources. Both can exist and seemingly contradict each other, too.

I think that kind of question asking is fair and that interrogation of self is necessary. The Eyes of Ghana is not the seminal Kwame Nkrumah film that explores and dissects the breadth of his legacy, but I think that story should be told. Hopefully, our film is a primer for what new questions we can begin to ask.

Beyond the screen and the critical reception, what impact do you hope The Eyes of Ghana will make, especially in relation to Chris Hesse’s mission and the broader revival of cinema culture in Ghana?

For the last 60 years, Chris Hesse’s mission has been to digitise the remaining archive for all of the world to see and for that footage to be repatriated back to Ghana. We stand by him in that goal.

We’re equally excited to support the ongoing work of getting Rex Cinema, an open-air cinema featured prominently in the film, back and running so that filmmakers can enjoy watching their films and screening others. There’s more work to be done, but we’re excited by the visibility that this film brings to Chris Hesse, Anita, Mr. Addo, Ghana, and a more robust storytelling future for the continent at large.

* The Eyes of Ghana premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival 2025 (TIFF) and has screened at several film festivals, from the BFI London Film Festival to the Africa International Film Festival (AFRIFF), and now, the African Diaspora International Film Festival (ADIFF).

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time watching, reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv