Casablanca – Dakar asks what happens when borders close suddenly; Seed is Life reminds us that for many Africans, they never truly opened in the first place.

By Joseph Jonathan

The pandemic did not invent immobility; it merely exposed how unevenly the world distributes the right to move, to stay, to belong. In March 2020, as borders snapped shut and nations retreated into themselves, freedom of movement became a privilege abruptly revoked, revealing the fragile scaffolding beneath modern life. At the TSWA Film Festival 2025, two films—wildly different in form, tone, and urgency—circle this question from opposite ends of the continent.

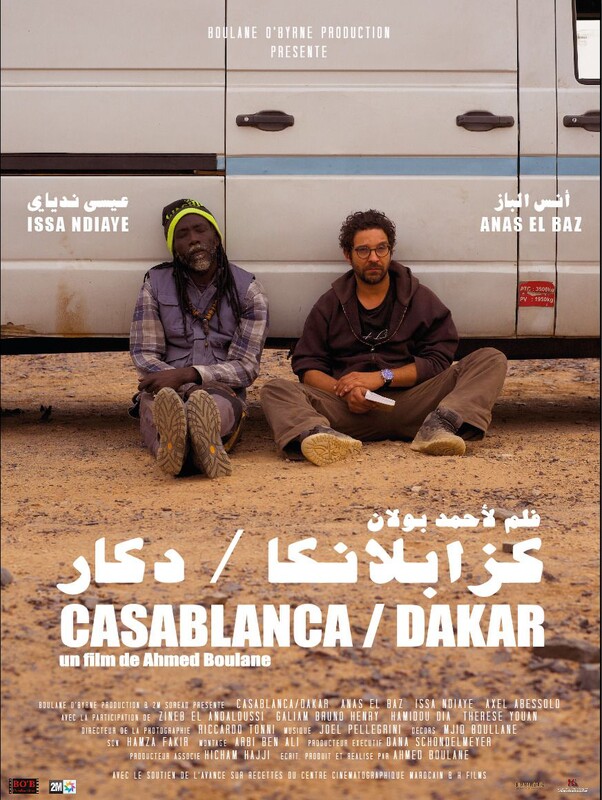

Ahmed Boulane’s Casablanca – Dakar turns restriction into a tragicomic odyssey, while Deidre May’s Seed is Life treats immobility as a political condition imposed on land, labour, and knowledge itself. Seen back-to-back, they offer a sobering meditation on what it means to be stranded; by borders, by policy, by systems that decide whose movement matters and whose does not.

In Casablanca – Dakar, movement is both desire and impossibility. Ali, a young Moroccan architect working in Dakar, is meant to be in Casablanca for the birth of his child. Instead, the sudden closure of borders leaves him suspended in a liminal space: physically outside his country, emotionally tethered to a life he can no longer reach.

What begins as a recognisably pandemic-era predicament slowly mutates into something older and more elemental: the road movie as existential trial. Boulane stages Ali’s predicament against the world’s largest desert, a vast, hostile expanse that strips the journey of romance and replaces it with dread, humour, and moral compromise.

The film’s tragicomic register works precisely because it refuses to sentimentalise Ali’s desperation. Around him are migrants imagining elsewhere as salvation, each drawn by the same mirage of escape. To resolve their collective impasse, they all turn toward illegality, choosing to cross the desert at a moment when the world itself has turned inward.

The irony is sharp: in an era defined by globalisation, connection collapses at the first sign of crisis, leaving individuals to negotiate survival alone. Boulane’s Western-inflected visual language—wide shots that dwarf human bodies, extreme close-ups that trap Ali inside his own thoughts—emphasises how small personal desire becomes when confronted by geopolitical indifference.

Yet, Casablanca – Dakar is not merely a pandemic parable. Its deeper concern is the arbitrariness of borders and the moral violence they enact. Ali is not fleeing poverty or war; he is trying to go home. That distinction matters. By placing him alongside undocumented migrants, the film destabilises easy hierarchies of deservingness. Freedom of movement, it suggests, is never guaranteed; it is granted, withdrawn, and negotiated.

The African musical score that gradually swells into symphonic drama underscores this tension, transforming individual crisis into something almost mythic. The desert becomes both obstacle and mirror, reflecting a world that has grown comfortable deciding who may pass and who must wait.

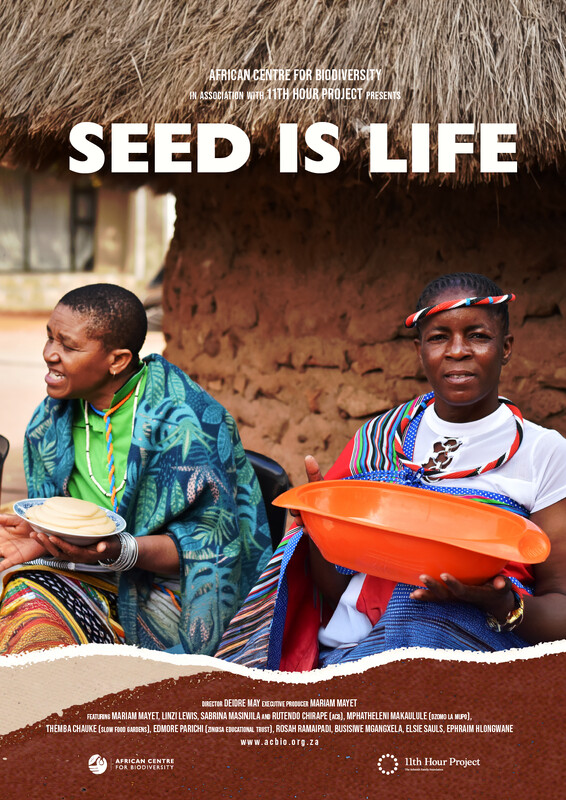

If Casablanca – Dakar stages mobility as crisis, Seed is Life interrogates immobility as policy. Deidre May’s documentary shifts the terrain from roads and borders to farms and courtrooms, revealing how smallholder farmers across Africa have long been immobilised by laws designed to serve corporate power. Where Boulane’s film follows one man stranded by a closed border, Seed is Life documents entire communities constrained by intellectual property regimes that criminalise ancient practices: saving, reusing, and sharing seed.

The documentary is at its strongest when it foregrounds women—four activists affiliated with the African Centre for Biodiversity—who narrate decades of encroachment on farmer seed systems. Their testimonies are not abstract critiques but lived histories of resistance.

Through South Africa and Zimbabwe, the film maps how indigenous seed systems have survived despite industrial agriculture’s attempt to render them obsolete. The stakes could not be clearer: between 80 and 90 percent of Africa’s food is produced by smallholder farmers, many of whom rely on farm-saved seed. To threaten these systems is to threaten food sovereignty itself.

What gives Seed is Life its urgency is its refusal to frame the seed as a mere resource. Seed is memory, inheritance, autonomy. The film patiently explains how even the corporate seed industry depends on the genetic diversity maintained by smallholder farmers, exposing the hypocrisy at the heart of agribusiness logic.

This tension reaches a legal crescendo in the documentary’s account of the landmark court cases opposing Bayer/Monsanto’s drought-tolerant GM maize in South Africa. The Constitutional Court’s 2025 dismissal of the government’s appeal is presented not as a triumphant endpoint but as a fragile opening, proof that resistance can succeed, but only through sustained struggle.

May’s direction is restrained, allowing farmers’ voices and legal histories to carry the film’s weight. Where Casablanca – Dakar relies on metaphor and landscape, Seed is Life insists on specificity: policies, court rulings, timelines. Yet the film never loses sight of its broader vision. It imagines a future rooted in agroecology, collective knowledge, and dignity: a future where farmers are not rendered immobile by law but supported by it. In this sense, the documentary is quietly radical, arguing that the right to move, to grow, to sustain life should not belong exclusively to corporations or states.

Together, these films reveal different faces of the same condition. One man stranded in a desert, entire communities bound to land they are told they no longer own; both are casualties of systems that regulate movement in the name of order, safety, or profit. The TSWA Film Festival 2025 could not have paired them more tellingly. Casablanca – Dakar asks what happens when borders close suddenly; Seed is Life reminds us that for many Africans, they never truly opened in the first place.

*Casablanca – Dakar and Seed is Life both screened at the TSWA Film Festival 2025 held in Abuja, Nigeria.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big.