Freedom Way uses its characters and its Lagos setting as a microcosm of Nigeria and its people, who somehow continue to survive incredible devastations and fatalities.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

In early 2020, a few days after Lagos State first banned commercial motorcycles, or okadas as we call them, in parts of Lagos, I got admitted into the Nigerian Law School. In typical Nigerian fashion, the notice was incredibly short, so even though I’d had the fees ready for months, I had a couple of days to make payment and travel from Lagos, where I live, to Enugu, where the campus I was posted to is located.

Arriving late to a campus with limited infrastructure would have dire consequences. So, I found myself running from bank to bank, with each bank unable to process payment, citing network issues with the government’s sole payment service provider. I needed to get around quickly.

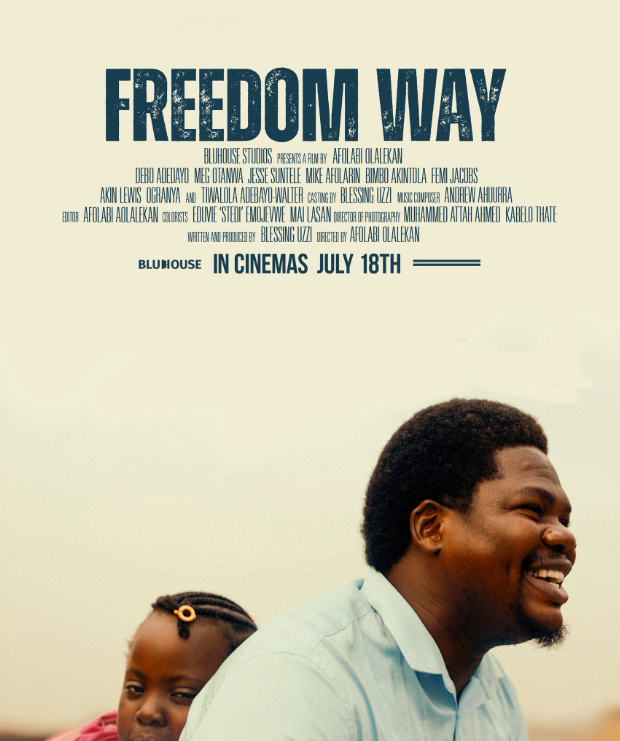

But Lagos had just banned okadas, including the tech-assisted ones with mobile apps. Motorcyclists were being violently rounded up by law enforcement. Buses were scarce. And I was frustrated. Yet, I had it good. The stakes were much higher for some, like the characters Blessing Uzzi creates in the Africa Magic Viewers’ Choice Awards 2025 Best Movie and BluHouse Studios’ cinema debut, Freedom Way (2024), directed by Afolabi Olalekan in his directorial debut.

While films that explore the casual ridiculousness of the Nigerian condition are not in short supply, the ones that approach the subject in truly remarkable ways are few and far between. The easiest film to reference here is Eyimofe (This Is My Desire) (2020), the critically acclaimed, Africa Movie Academy Award-winning drama written and directed by Arie and Chuko Esiri.

Freedom Way is the latest in the class (possibly to be followed by Ema Edosio’s When Nigeria Happens (2025), which is currently on the festival circuit, though the jury is still out on that one). But where the Esiri Brothers are subtle and prioritise the little things over big events, Uzzi and Olalekan prioritise the big events and put the country’s systemic dysfunction on loud display. And where Eyimofe’s subjects are individuals on the lower rungs of society, Freedom Way is more conscious of the country’s situational, philosophical, and class diversity.

The film’s title itself is derived from a major road in Lekki. But Freedom Way could not be more different than the flashy, reality-detached films we’ve come to identify with the location. In fact, that Freedom Way situates some of its defining moments in a high-brow part of Lagos is an intentional reminder that Nigeria can happen to anybody. And it sure does touch everybody in Afolabi Olalekan’s fierce film.

Produced and written by Uzzi, Freedom Way follows nine individuals whose lives intertwine over a few chaotic days in Nigeria’s commercial capital. The state government has just banned commercial motorcycles, a policy that sets off a domino effect for the film’s ensemble, most of whom are fighting to survive the fallout. But as it is said in these parts, you can’t outhustle Nigeria. The more they try, the more they run into systemic roadblocks that no sane person should be able to anticipate.

Practically every moment of Freedom Way highlights Nigeria’s dysfunction, how it wrecks and ruins, and how easy it can be to lean into that dysfunction when it just happens to work in your favour. But it also captures the resilience of the average Nigerian, with the film’s characters ceaselessly striving to rise above their situations, no matter how bleak. That Freedom Way connects and revolves around nine lives (ten, if you count children) is symbolic in itself. After all, to have nine lives is to have an extraordinary ability to survive life’s most damaging curveballs.

And so, Freedom Way uses its characters and its Lagos setting—a function of the cinematography, editing, and the story itself, Lagos is more a character in this film than in any of the recent films that have had Lagos in their title—as a microcosm of Nigeria and its people, who somehow continue to survive incredible devastations and fatalities.

The dramatic chain of events begins with two well-to-do tech bros, Tayo (Ogranya Jable Osai) and Themba (Jesse Suntele), who have just obtained government approvals for their new commercial motorcycle hailing app when the policy strikes. Their friend, Edidiong (Mike Afolarin), is a lawyer who has secured his japa route and already has a one-way ticket out of the country.

Edidiong is so completely disillusioned with his country to the point that he thinks about the safety of his passport before the safety of his mother and has accepted abuse of power by the police as a necessary evil. But Themba, a South African unable to fathom the extent of his host country’s insanity, thinks Nigeria can change, and his Nigerian friend, Tayo, is caught somewhere between hyperawareness of the country’s failed system and an idealistic approach to dealing with said system.

There’s the lower-class family man, Abiola (Debo “Mr. Macaroni” Adedayo, expertly riding through varied emotions), a commercial motorcyclist, and his seamstress wife, Funke (the dependable Meg Otanwa), neither of whom has the privilege of dwelling on the subject of dysfunction. Abiola and Funke just want to make enough money to pay their brilliant daughter’s (Tiwalola Adebola-Walter) school fees before graduation day. And if it’ll take becoming the oppressor to provide for and protect his family, Abiola may not even think twice.

There’s also Dr. Cheta (Taye Arimoro), a medical doctor whose partner comes from wealth, and who’s frustrated by the ridiculous ways the system trivialises life, but who ultimately gives in to the system in an act of self-preservation—at great cost to him, ironically. There’s a wealthy businessman (Akin Lewis) whose automobile business interests are being served by the motorcycle ban, and his daughter (Teniola Aladese), whose NGO for underprivileged children is funded by her father’s business, which itself helps keep underprivileged children underprivileged.

And then, there’s the corrupt police officer who is a literal enforcer, ensuring that the vicious cycle continues to turn. Officer Ajayi (played by Femi Jacobs, enjoying his performance so much that we have to enjoy it, too) is as callous and reckless as they come, relaxed in his knowledge that there are no consequences for bad behaviour, even after his superior officer (Bimbo Akintola) has issued him a final warning.

Officer Ajayi has positioned himself to milk the circumstances for all they’re worth, but he would not be at checkpoints every night trying to make a few extra notes by extorting drivers and passengers if he himself were not a victim of the system. It’s his recklessness that kicks down the penultimate and fatal domino, but he is as much an effect as he is a cause.

If you haven’t experienced Nigeria, you might accuse Freedom Way of laying the dysfunction on thick. Or you might find some of its plot points or character actions implausible, just like Themba, the optimistic South African character whom the filmmakers employ as a lens to remind us, Nigerians, that nothing about the Nigerian condition makes sense. And this is what makes films like Freedom Way important: that much needed reminder that our norms are in fact not normal.

To be fair, the events of Freedom Way are sometimes too convenient. The interconnectedness, in particular, is extreme. That unrelated characters have some sort of connection that ties their distinct stories together into one bigger picture is a feature that Freedom Way shares with Eyimofe. But unlike Eyimofe where it was simply a shared neighbourhood and a landlord, there’s an over-weaved web of connections between the characters of Freedom Way, so much so that you may find yourself distractedly playing “guess the relationship”.

Regardless, Freedom Way’s strongest merit is its writing, which earned it the AMVCA for Best Writing. Uzzi deftly knits so many characters into a coherent story, with a steady and pretty straightforward narrative flow, all situated within a neatly set out three act structure. Even the over-connectedness is, at least, well sewn and serves to heighten the stakes.

Freedom Way is fast-paced, and it can feel like too much is happening, especially considering that the events of the film span across a few days. But the overwhelming feel works for the concept and for what it represents—a city that does not rest, and a reality where every individual is just one government policy, one technology disruption, one medical emergency away from implausible chaos.

Rating: 4.1/5

*Freedom Way premiered at the 2024 Toronto International Film Festival on 7th September 2024 and opened in Nigerian cinemas on 18th June, 2025.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time watching, reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv