What ultimately undermines much of 3 Cold Dishes’ emotional promise is the patchwork of acting performances that never quite find the same register.

By Joseph Jonathan

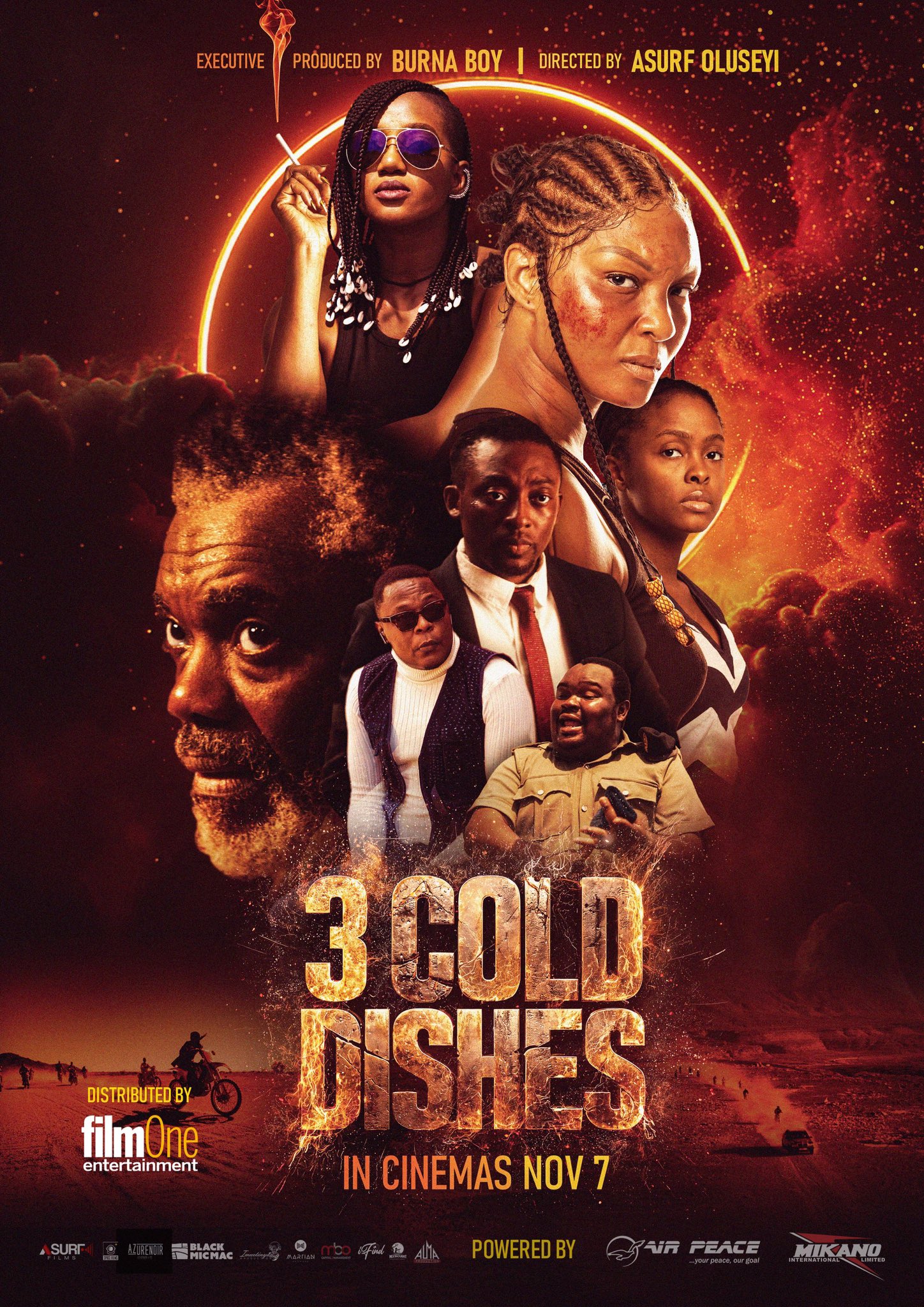

3 Cold Dishes, directed by Asurf Oluseyi and executive produced by music superstar, Burna Boy, promises a revenge fantasy dressed in pan-African swagger. The premise itself is irresistible: three women, once trafficked as teenagers in 2002, reappear sixteen years later as hardened outlaws determined to serve justice themselves since the state never bothered to try.

But from its first breath, the film reveals a restlessness—a desire to be many things at once: a crime thriller, a spiritual fable, a pan-African action romp, a feminist lament, an exposé of human trafficking, a Kill Bill-esque spectacle. In reaching for all of these identities, it loses the one thing that matters most: a centre.

The story unfolds through Mama Janice (Amelie Mbaye), the streetwise madam-turned-historian, whose narration is meant to bind the timelines together. Her voice is enthusiastic, spiky, and colourful, yet the device becomes a chokehold, interrupting scenes just as they gather force. It is not her fault; she is merely a symptom of a film unsure of how to trust silence, how to trust emotion, or how to trust the women whose pain it claims to honour. Every time Mama Janice pivots from anecdote to major plot reveal with the abruptness of a Lagos radio ad, the emotional membrane of the film tears a little. This is a story begging to be felt, but instead it is constantly being reported.

The trio at the film’s heart—Fatouma (Fat Toure), Esosa (Osas Ighodaro), and Giselle (Maud Guerard)—carry the raw material of a powerful tragedy. Their individual backstories drip with the quiet cruelty that is a hallmark of our region’s trafficking crisis.

Fatouma, a young Ivorian girl, is deceived by her pastor, who dangles the promise of a football contract in Paris before handing her over to traffickers. Esosa from Nigeria suffers a similar fate when her Uncle Bankole (Wale Ojo), tricks her into travelling with him, only to deliver her into the same network in Abidjan. Giselle, already vulnerable and isolated, is sold by her grandmother to a local chief whose abuse becomes the beginning of her nightmare.

On paper, these origin stories are devastating. On screen, they flicker by like broken signals. 3 Cold Dishes treats the girls’ most formative traumas like calendar reminders—events to check off, not experiences to embody. It is perhaps the greatest betrayal of the film’s premise: the refusal to sit with pain long enough for it to become meaningful.

Where the film does find occasional grace is in its textured understanding that liberation is never a straight line. Even after escaping their traffickers, the women are folded into new systems of male power—a General, a politician, petty criminals—circles within circles of exploitation masquerading as opportunity.

3 Cold Dishes’ strongest thematic gesture is its refusal to pretend that abuse ends when the first villain dies. Instead, it shows how the girls become women without ever becoming free, how trauma calcifies into purpose, how revenge becomes the only language left when hope has expired.

But the execution never matches the weight of its ideas. The supernatural thread woven through Giselle’s story feels like an import from a different movie entirely, an over-seasoned ingredient that spoils the broth rather than enriching it. Her spirit “possession” functions neither as metaphor nor mystery; it simply hangs, under-explored, like a prop waiting for instruction. In a film already struggling to anchor itself, this mystical detour deepens the confusion.

Cinematography, however, emerges as the one department unbothered by the script’s indecision. The camera moves across borders with a confidence the narrative lacks, gliding through Lagos’ neon grit, pausing in the sun-washed quiet of Benin’s outskirts, tracing the sandy stillness of Ivorian border towns. The landscapes tell the story the script does not: of a region stitched together by shared danger and shared dreams, of young women who could have belonged anywhere but instead belonged to no one.

What ultimately undermines much of 3 Cold Dishes’ emotional promise is the patchwork of acting performances that never quite find the same register. The film’s most affecting work comes from its younger cast: Ruby Akubueze as the teenage Esosa trembles with a rawness that feels peeled straight from a documentary, and the early ensemble scenes crackle with the sincerity of girls who have not yet learned to hide their terror. But once the narrative leaps forward in time, a kind of dramatic dissonance settles in.

Osas Ighodaro, as the older Esosa, often feels like she is reaching for an emotional centre the script does not provide; Fat Touré often leans into rage with a single-note intensity that flattens her character’s complexity; and Maud Guerard is left stranded by a role so thinned out by shaky supernatural writing that her performance becomes less a portrayal than a survival act.

Among the men, Wale Ojo is the one performer who seems to understand the film’s moral terrain: his Uncle Bankole is rendered with a chilling calm, a reminder of how evil in West African society rarely announces itself with theatrics but with quiet entitlement. It is this inconsistency—between those who fully inhabit the film’s world and those merely passing through—that prevents the story from achieving the emotional cohesion it so urgently demands.

What 3 Cold Dishes ultimately reveals, perhaps unintentionally, is something deeply African: our collective discomfort with interiority. We recount trauma, but rarely explore it. We dramatise violence, but rarely interrogate the psyche it corrodes. The film mirrors this cultural habit. It shows the wounds, but not the healing—or the failure to heal. It names the monsters, but not the long shadow they cast inside the women who survived them.

In the end, 3 Cold Dishes is a film caught between ambition and clarity. It wants to indict human trafficking, celebrate female vengeance, traverse borders, critique institutions, and nod to pop-culture bloodlust, yet it forgets to build the emotional bridge required for us to walk with these women. The revenge, promised cold, arrives lukewarm. The trauma is introduced hot, but cools too quickly. The film’s reach exceeds its grasp, and in that gap lies a beautiful frustration: a work that could have been great but settles for surface-level.

Still, there is value here. In its multilingual swagger. In its cross-continental gaze. In its attempt—flawed but earnest—to confront a deeply African crisis with the scale it deserves.

3 Cold Dishes is a reminder that telling stories about our broken systems is not enough. We must also tell stories that understand the broken people inside them. And until Nollywood learns how to do that with depth rather than speed, our revenge sagas will remain stylish, ambitious, and ultimately incomplete.

Rating: 2.3/5

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big.