“With Carissa’s foundation, we aim to continue to make films with themes of freedom, indigenous identity, ancestry, female resistance, land, memory and legacy.” — Deidré Jantjies.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

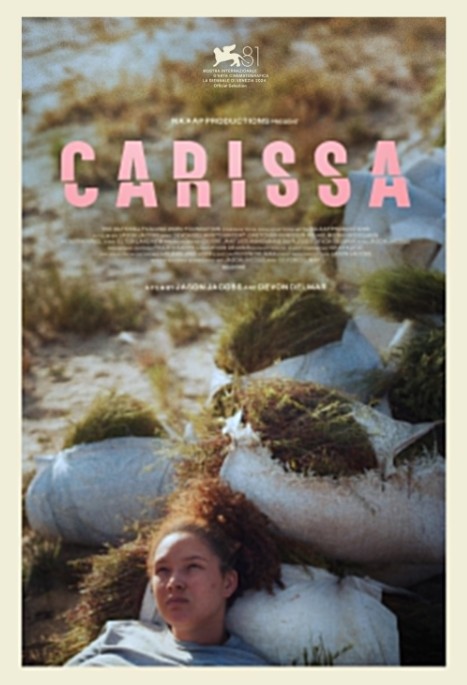

Debut features that are coming-of-age films tend to be deeply personal stories. Carissa (2024), the picturesque and relaxing debut feature from South African writing-directing duo Devon Delmar and Jason Jacobs, co-produced by Deidré Jantjies and Annemarie du Plessis, is no different. Indeed, it is a more personal and communal experience than most, blurring the line between fiction and the lived reality of its cast and crew.

Shot and set in Wupperthal, a small town in South Africa’s Cederberg mountains, where rooibos tea is the most valuable cash crop, the Afrikaans-language film follows the titular character on a journey of self-discovery as she finds value in nature and her place in community. Delmar and Jacobs draw from their individual stories and rely on the members of the Wupperthal community in crafting an immersive meditation on indigenous identity, responsibility, community, and the conflict between tradition and modernity.

Played by Gretchen Ramsden, Carissa spends her day scrolling through her phone or hanging out with her friend (Gladwin van Niekerk), mostly in a tavern where they play games and get drunk. Under scrutiny from her grandmother (Wilhelmiena Hesselman), who finds her to be rebellious and wants her to apply for a training opportunity with a company that is developing parts of the town into a golf estate, she dreams of an escape, but not quite to a place as ambitious as the big city.

When Carissa gets into trouble and has to leave home, she joins her estranged grandfather (Hendrik Kriel) on his fields, where he plants and harvests rooibos tea. It takes some adjusting, but as Carissa settles into life on the farms, she grows to become more attuned with nature and more conscious of her environment, her family, and her own self. But with the tea farms turning into a golf estate, Carissa is set to lose parts of herself and her heritage that she has only just discovered.

Carissa has made its mark both home and abroad, making its world premiere at the Orizzonti section of the Venice International Film Festival in September 2024 and opening in South African theatres one year later.

In an interview with Afrocritik on the sidelines of the 2025 African Diaspora International Film Festival (ADIFF), directors Devon Delmar and Jason Jacobs, and co-producer Deidré Jantjies reflect on Carissa, the communal approach to the filmmaking process, and the thematic concerns at its core, from intergenerational care to gentrification.

* This interview has been edited for clarity.

What inspired the story, and in what ways was it shaped by your background or experiences?

Jacobs: Thank you for the question. Carissa was developed over a beautifully long period, with the story being shaped through early workshops together as a duo and with and alongside the community of Wupperthal. Our personal experiences inspired the world of the story at the time of writing it.

Carissa, the character, was inspired by our intention to write about or give space for other ways of telling the coming-of-age story. Something a little like Rosetta and a bit like Lady Bird or Olive in Little Miss Sunshine. Characters who are seen as flawed by society’s standards, and introducing a world of stories that we need to know about today. Sharing experiences, particularly focusing on the perspectives of those who remain unheard. We were also quite interested in the question of parenthood, especially fatherhood and what makes up the nuclear family in modern times.

Delmar: As writers and storymakers, over [the] time of developing, especially the script, we grew more curious about the more-than-human world. Carissa’s introduction was a natural fit, given that she is always on her phone screen when we meet her, and changes as a direct result of her journey.

As we developed the story, we were fortunate enough to be invited to the Wupperthal community (where the film is based) many times over the years, where we spent special time with the friends we made, but especially the mountainous landscapes, where one is invited to engage with natural and magical elements. The wind has remained a constant influence in our work, which is what ultimately influenced how we wanted the viewer to experience Carissa’s journey; a journey of listening to nature and realising there is a different world that exists outside of our human-centric selves.

Jacobs: Carissa’s story echoes many parts of our own lives. Like Carissa, I am a carer for my grandmother in the later stages of her life, who also lives in a small community similar to Wupperthal, which is Kharkams. Having worked in Wupperthal, we have been motivated to make films centred on community building and narrative approaches that prioritise this focus.

We have both felt the push and pull of our families’ and communities’ expectations on us, the need for us to go out into the world and ‘make something’ of ourselves, to be a ‘success’; all of this within and around our own processes of making sense of the world, and ultimately of unlearning many things we’ve been taught.

Carissa reflects the experiences of many young people who distance themselves from family or community expectations as they search for escape, identity, and self-definition. What were you aiming to explore through her character, and how did you direct Gretchen Ramsden to achieve that?

Jacobs: Very glad that you brought this up. We agree that Carissa distances herself from her family, but she already, from the start, challenges what is expected of her. Even today, we see how many of our young people feel lost and almost directionless, especially those who are at the brunt of unemployment at such an early age and the mounting pressures of needing to assist at home or sometimes fully provide for the family.

In small communities, from what we have seen, government work opportunities are very popular amongst young people, single parents or unemployed youth. However, there are the Carissas in the world who wish to make their own choices despite being in conditions where it is difficult to do so.

Delmar: Gretchen brought her own understanding of this internal tussle to the character, and she knew who Carissa was. Directing Gretchen is a form of play; we listen and respond, and she does the same. She went through her own process of immersion in Wupperthal, with deep listening and attention, and all we had to do was stay on track with Carissa’s arc and act as guides.

The film pays notable attention to Carissa’s hair and how she has to wear it for certain occasions. In one scene, her grandmother straightens her hair with a pressing iron for church. In another, she curls it back. What role did her hair play in expressing her personality vis-à-vis social expectations?

Jacobs: Such great questions! Our hair significantly shapes our sense of self. Hair presentation is deeply rooted in and inherited from previous generations and cultural practices. Within the indigenous and Coloured communities, in particular, hair and its styling are significant factors in both personal presentation and broader representation.

In smaller communities, hair has been tied with the social expectation of needing to straighten your hair for church or special gatherings like matric balls or even weddings. Of course, many people have embraced their natural looks, inspired by the movement to fully champion their indigenous identities, as exemplified by [our] producer Deidré Jantjies.

Due to the history of trying to keep the hair straight and neat, it did take the Coloured community a long time to understand their natural roots. Carissa is not necessarily against any form of how indigenous people wish to represent themselves today. Before Carissa gets a chance to leave the village and be in the sacred landscapes of her forebearers; she most likely never engaged in conversation about how she is ‘seen’ in the world.

While Carissa is the central character, the film leans on parental figures, particularly her grandparents, to paint a picture of her relationship with both her family and their community. What guided your decision to foreground these dynamics?

Jacobs: The decision was based on our approach to make everything as authentic as possible. The relationship between Carissa and her parental figures is in no way unique in the families we come from. The relationship itself, however, takes on multitudinous identities; an identity of care from the elders to the young, for example. There are many places in the film whereby we make this explicit; for example, the scene where the father and daughter are washing dishes together in the last act of the film. It is an act of care, of rebuilding trust.

Delmar: This is an instance where we question the conventional roles of a father in a house, but stay authentic to our daily experiences. In the bigger picture, one can think of all the guardians of Carissa as a singular unit, encompassing both grandparents and parents. This unit is one that has survived uncountable hardships in life and comes with a desire to make things easier for the next generation, so that they can have the kind of future that they hadn’t had themselves. It is this understanding that their care stems.

It is interesting that Carissa’s grandparents and some other characters are named after their actors, who are not actually professional actors. How much of the film emerged from the real-life community and from immersing yourself in the people and environment you were filming?

Jacobs: We spent a large amount of time with the community, where their real-life stories inspired how we approached the film. We learned there is power in the pride of representing a version of yourself in a fictionalised story, meaning you too are acting. There is really no separation between the ‘actor’ or community member because each brings with them a wealth of wisdom on how to embody the story presented for them to be a part of.

Delmar: There was a point where our imaginations tipped over into the metaphysical, and we started thinking about how we are all, in some ways, ‘play-acting’ our individual selves, all the world is a stage, we are refractions of the light of the one self, etc. We won’t delve too far into that here, but that foundation was nevertheless useful to approaching the idea of people playing themselves on screen.

And again, it comes with a certain amount of play and looseness. There’s a chance for actors like Wilhelmiena (Hesselman), Hendrik (Kriel), Edgar (Valentyn) and others, all playing characters with their own names, own clothes, own houses, own manner of speaking, to recreate something out of the old and new, with the fictional and the real. A common question that we ask [as] directors would be, ‘how would you react if such and such were to happen?’

And again, as the writers of the story and following through with our vision over numerous iterations over the years, we know the vision and are there to keep the guardrails on the story we’re telling. But letting the environments and the actors do their thing, as it were. Our early casting and location scouting had to be on point, crucially, to allow for that freedom on set. The job of the director is to assemble the right ingredients; if you do it right, the pot then stirs itself.

Jantjies: As a producer, my journey started with a focus on activism to ensure that Southern African indigenous stories are told with heart and honesty. In my view, this involves incorporating a structure that diverges from Western storytelling conventions. Instead, I embraced an indigenous methodology that actively involves community members in the storytelling process. This approach respects and integrates the voices and perspectives of the people connected to these stories, ensuring authenticity and cultural integrity.

Building on this foundation, while producing Carissa, I did my best to think outside the box and find ways to bring inclusivity into the workplace. This initiative led to the creation of a professional space for the community of Wupperthal, where we filmed, empowering them both financially and creatively.

A pivotal plot element is the planned construction of a golf estate, which is an opportunity for development but also a catalyst for gentrification that threatens the community’s tea fields. What perspective were you hoping to offer about gentrification through this storyline?

Jacobs: We are witnesses to many injustices in the world related to the destructive nature of gentrification and how it has robbed marginalised communities of their identity, erasing ancestral spaces for the good of capitalism. It is usually a process whereby we observe the trade of ancestral heritage for poorly defined definitions of modernity in a capitalist society. The act of theft not only has a direct impact on the structures which had existed, but also directly impacts the livelihood of ancestral practices altogether. The erasure of such spaces leads to the demolition of culture, language, and identity.

In the film, this demolition is also literal. It leaves future generations oblivious to the power of the soil, their place of birth; isolated with a severed connection to their true self and often lost as a familiar place such as home ceases to exist. The overall effect is an ungrounded community with lost and often misunderstood individuals longing for a place in which their ancestors cultivated peace, which, with gentrification, becomes permanently inaccessible. Like with all of our themes, the threat gentrification poses to the community in the film is one that is not overly emphasised.

Delmar: We also acknowledge what development at this scale can provide for communities where unemployment is rife. We have to raise that counter-argument. However, it is very important to raise awareness on destructive takeovers on indigenous land and, as a result, the erasure of indigenous practices and the sacred. It is our way of reminding the world that these things exist and that the invasion on sacred land and ways of being has and continues to have a great impact on the lives of those mostly affected today.

When Carissa asks where the farmers will plant tea after the golf estate is built, the film offers no answer. Why was it important to leave that concern open-ended?

Jacobs: We think the audience will harvest their own final response to this moment. It is a question answered with a shrug. What do you do when your land is taken from you, when all you know are the mountains, and the growth and harvesting of rooibos is all you have?

Delmar: As Hendrik says later, when asked if he couldn’t move in with her, he doesn’t belong in the village.

Jacobs: For Carissa, it is centred on her choice whether to stay and ‘takeover’ the land. She is most definitely innocent and is, in a way, pushed into a corner, as any inheritance comes with a lot of responsibilities. It is a very romantic idea to believe that Carissa will eventually be able to survive in the land should she decide to take over from her grandfather. She remains naive in this way because she has so much to learn.

What were some of your favourite moments that captured Carissa’s essence or the heart of the story?

Delmar: The film’s most resonant elements, in our view, are about nature as a focus and characters, which weaves with Carissa’s story. While her journey involves personal change, there is a shift away from her phone as the film goes on. And an awakening to her environment. This transformation is linked to the visuals of nature and its symbolic role within the narrative.

The story of the donkeys, as an example, and their own story in the film, is particularly impactful. We love that shot of the donkey in the lounge. It is the final moment where the dam wall has burst, so to speak. That moment that the donkey stands in Ouma Wilhelmiena’s house comes at the end of a lifelong struggle to reject the indigeneity of her ancestry and identity, and the multifaceted things that that represents.

With her predilection for a certain kind of Englishness, through her love of Princess Diana, her obsessive cleanliness, her rose garden, and her attempts to get Carissa to ‘elevate’ herself, there’s this idea that she aspires to a kind of Westernness. She’s trying to grow delicate red roses in the Cederberg veld, and yet these ‘ugly’ cactuses and botterbome keep on impinging on this imaginary fence between her world and the backwards veld, the untamed world that Hendrik represents.

The goat leans over the fence to eat her trees, she chases the geese away, she waters her roses, she straightens Carissa’s hair with an iron, and yet little things keep impinging, even a fish from the river slips inside her bottle. And at the end, when she’s at her weakest, there the donkey is inside. And it represents for us the final crack in her armour. Carissa grows her hair long now, and now that Ouma’s defences have crumbled, she can finally start to be who she wants to be.

Jacobs: Similarly, the wind acts as a powerful, non-human character, embodying the emotional challenges and growth of Carissa as a character. Everything happening in her surroundings serves as an invitation to develop a perspective that moves beyond her initial, human-centred view. A view we hope others can also experience by watching the film.

After an eventful year for Carissa, what direction do you see your filmmaking taking next? Are there particular stories or themes you’re eager to explore?

Jantjies: With Carissa’s foundation, we aim to continue to make films with themes of freedom, indigenous identity, ancestry, female resistance, land, memory and legacy.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time watching, reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv