Perhaps the tragedy of Osamede is that it understands the importance of its story but not the grammar of its telling.

By Joseph Jonathan

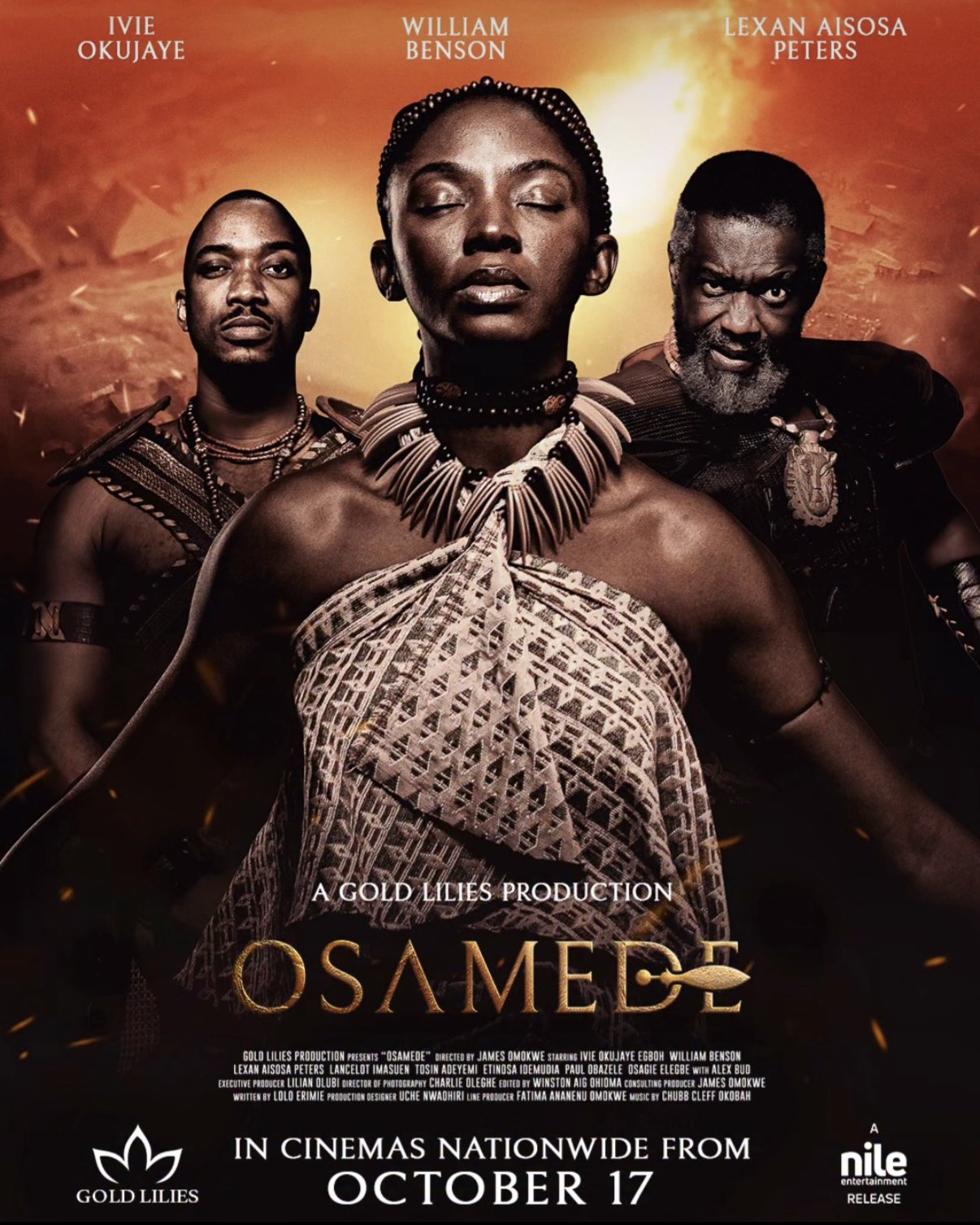

Nollywood has always flirted with myth. From the forest spirits of Igodo: The Land of the Living Dead (1999) to the ancestral reckoning of Aníkúlápó (2022), Nigerian cinema often dreams in the language of gods. Osamede, the historical epic from director, James Omokwe and executive producer, Lilian Olubi, extends that tradition; a film that seeks to retell the story of the 1897 Benin invasion through the lens of spirituality and feminine heroism. But while it aims for transcendence, it ultimately collapses under the weight of its own ambition, caught in the uneasy space between stage and screen, myth and memory, idea and execution.

Adapted from a 2021 stage play by Olubi, Paul Ugbede, and Tosin Otudeko, and adapted for screen by Lolo Eremie, Osamede promises a sweeping reimagination of a painful chapter in Nigeria’s colonial history—one that still echoes in conversations about restitution and identity. Yet, what unfolds is a film that mistakes mythic posture for cinematic power, leaning heavily on language and lore while failing to forge a visual or emotional core strong enough to sustain its promise.

The story begins during the British Punitive Expedition of 1897, which saw the Benin Kingdom burned, looted, and stripped of its sacred artefacts. Amid this turmoil, Iyase (William Benson), the Oba’s ambitious general, seeks to harness the supernatural power of the Aruosa stone — a divine relic said to channel the strength of Osanobua, the Supreme Deity — to repel the invaders and, secretly, usurp the throne. The priestess, Adaze (Tosin Adeyemi), refuses to surrender the stone and, in desperation, performs a forbidden ritual that transfers its power into her unborn child. That child is Osamede.

Two decades later, Benin is under British rule. The people toil in colonial mines, their dignity buried beneath layers of humiliation and fear. Osamede (Ivie Okujaye), raised by a humble blacksmith, Agbokhai (Paul Obazele), is restless and defiant. She confronts injustice wherever she sees it — defending women from domestic abuse, intervening when miners are whipped — long before she understands the divine energy that burns inside her. One violent encounter with a British officer, who attempts to assault her, awakens that buried power. Flames consume her attacker, and for the first time, Osamede sees herself not as a victim of empire, but as a vessel of retribution.

From here, the story should ascend into myth. Iyase, freed from captivity, rallies his loyalists to reclaim the stone’s power. Osamede flees with Nosa (Lexan Aisosa Peters), a translator torn between service to his British masters and loyalty to his people. Together, they seek refuge in Iyamu, a mystical sanctuary where Osamede must learn the meaning of her power, and her destiny. On paper, this is potent material: the child of resistance confronting the sins of her ancestors while an empire rots from within.

But the cinematic treatment rarely honours that promise. What should feel like an odyssey of self-discovery often unfolds as a sequence of loosely connected vignettes. The film retells key events through flashbacks and narration, sometimes redundantly, as if unsure that its audience will keep up. And while the Bini dialogue gives it cultural authenticity, the storytelling falters under the weight of exposition. Scenes that should move us: Adaze’s sacrifice, Osamede’s flight, and Iyase’s betrayal arrive without rhythm or urgency.

To its credit, Osamede makes one bold, admirable choice: it tells its story almost entirely in Bini. This decision, in a landscape where indigenous languages are too often traded for English gloss, is revolutionary. It asserts that historical cinema in Nigeria doesn’t need translation to have reach — that our tongues can carry grandeur. The film’s linguistic texture becomes a defiant act of preservation; it reclaims the soundscape of precolonial Benin with quiet pride.

Yet language alone cannot save a film that lacks a visual imagination. Omokwe’s direction often feels like an extension of stagecraft, where emotion is conveyed through dialogue rather than through image. Scenes unfold in static, wide compositions; the camera observes but never interprets. The few moments of fluidity — such as a crane shot gliding over the miners during a tense confrontation — hint at a more dynamic aesthetic that the film never fully embraces.

Then there’s the baffling use of AI-generated imagery during Aigbangbe’s narration. Meant to visualise the ancient myth of the Aruosa stone’s creation, these sequences resemble a slideshow of distorted faces and digital fire, an aesthetic choice so anachronistic it rips the viewer out of the film’s world entirely.

One might defend it as a budget-conscious experiment, but the result is closer to distraction than innovation. Stylised 2D animation or shadow puppetry would have better honoured the story’s mythic tone. The gods of Benin deserve more than what looks like an algorithmic hallucination.

If Osamede endures at all, it is because of Ivie Okujaye. Her portrayal of the titular heroine is layered, fierce, and deeply empathetic — the kind of performance that anchors even the most uneven storytelling. She carries Osamede’s burden of destiny with both fragility and fire. When she screams against oppression, or sits in silence after discovering her power, we glimpse the film that Osamede could have been: intimate, haunted, alive.

But the surrounding performances rarely match her intensity. Benson’s Iyase is compelling in outline but not execution; his menace fades beneath flat dialogue and perfunctory staging. Lexan Peters’ Nosa, written as Osamede’s moral and somewhat “romantic” counterpart, never rises beyond bland civility. Their supposed chemistry is reduced to hand touches and exchanged glances that evoke neither longing nor tension. And the British soldiers — stiff, miscast, and painfully awkward — collapse under the burden of their accents, a reminder that Nollywood still struggles with casting foreign roles convincingly.

Thematically, the film gestures toward rich moral terrain — destiny versus choice, resistance versus complicity, power versus justice — but it never digs deep enough. Osamede’s awakening through sexual violence could have been a profound moment of gendered defiance, a subversion of the colonial gaze that has long fetishised the African female body. Instead, the scene is treated as a plot device, not a point of reckoning. The film rushes past trauma, preferring divine empowerment to human recovery. That elision is not only dramatically weak; it’s morally timid.

What Osamede attempts, conceptually, is admirable. To blend real history with speculative spirituality is to acknowledge that our myths were once our politics. The Aruosa stone becomes a metaphor for cultural restitution — for everything the British stole that can never be returned. When Osamede says, “I only fight for others”, her mother replies, “It is a special thing to fight for others”. That exchange captures the moral heart of the film: a people’s salvation lies not in power, but in selflessness.

And yet, Osamede undermines itself by failing to create a believable world. The costumes are muted when they should blaze with ritual vibrancy; the sets feel sparse and temporary; the extras move with the self-consciousness of rehearsal. The film wants to be epic but feels miniature — not because of its budget, but because of its indecision. Minimalism could have been its saving grace; a deliberate, meditative austerity like in Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu (2014). Instead, Osamede oscillates between grandeur and flatness, never quite choosing a cinematic identity.

The pacing further saps its energy. The early acts, built around Osamede’s defiance and the miners’ revolt, pulse with promise. But once she begins her journey to Iyamu, the narrative drifts, the editing loses rhythm, and what should be an ascension becomes an endurance test. The film’s final act, meant to climax in spiritual revelation, arrives hurried and underwhelming. Even the action sequences — precious few of them — lack the tactile energy of struggle; they are choreographed gestures rather than visceral confrontations.

Despite its many flaws, Osamede is not without importance. It represents a growing movement within Nollywood to reclaim language, history, and myth as tools of cinematic identity. Hearing Bini spoken with pride on screen is itself a quiet revolution. For a moment, one can imagine an industry where every culture within Nigeria has the chance to mythologise itself in its own voice.

But cinema, unlike oral storytelling, demands precision — not just sincerity. Osamede mistakes intention for achievement. Its heart beats loudly, but its form betrays it. Every grand idea — colonial critique, feminist awakening, spiritual inheritance — is there, buried beneath uneven craft and timid imagination. The film wants to soar, but its wings are made of stage curtains.

Perhaps the tragedy of Osamede is that it understands the importance of its story but not the grammar of its telling. It speaks with the conviction of a sermon but moves with the hesitance of a rehearsal. In trying to honour its gods, it forgets to trust its cinema.

In the end, Osamede is a parable of its own making; a story about potential that never quite manifests. It reminds us that cultural ambition must be met with cinematic discipline, and that the divine deserves better lighting.

Rating: 2.5/5

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big.