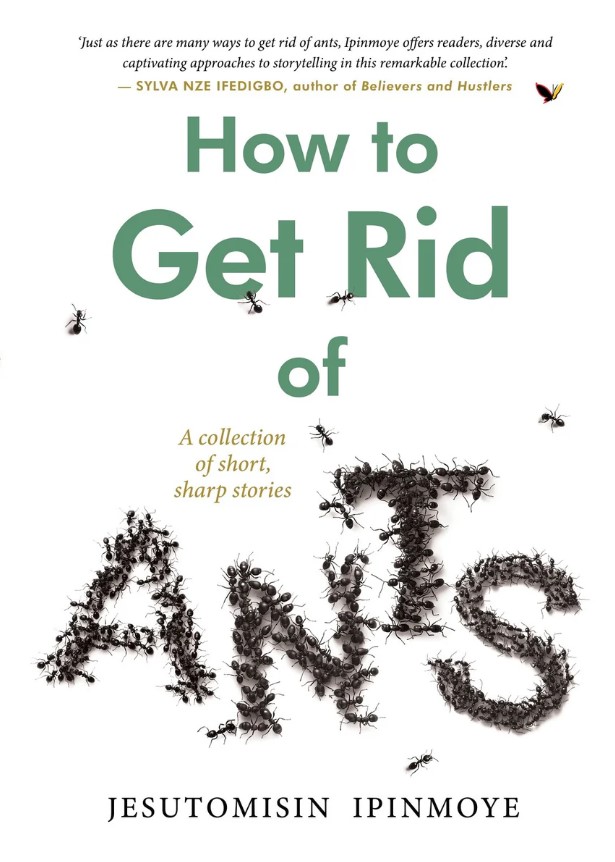

How to Get Rid of Ants is the makings of a master of the form. Like a diamond glinting from all angles, Jesutomisin Ipinmoye is a talent to watch.

By Azubuike Obi

Every so often, we encounter books that shift something in us; some for the honest interrogation of their subjects, others for the manner in which they challenge the status-quo. I remember reading Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater (2018), and being stunned by the sheer audacity of the mind that put down such hallucinatory work; a novel that refused to be contained in the boundaries of genre or voice. Jesutomisin Ipinmoye’s debut collection, How to Get Rid of Ants, is one of such works: it pushes the boundaries of what is familiar, while staying rooted in a firm sense of place.

Released by Parrésia Publishers in March 2025, How to Get Rid of Ants is a collection of fifteen stories – stories that pulsate with life, that test and try to attest to a true humanity. Stories familiar, yet rendered bizarre in their presentation.

How to Get Rid of Ants opens with “this space should have been left blank”. A proud man and God wrestle in this brilliant note on revenge, reincarnation and the enormous power of will. Pa Gbenga is a man “with planted feet, a loose thread at the end of your trousers that you’re scared to pull lest you weaken the entire garment”. Fully fed, he challenges his God to a tryst. The story follows not just Pa Gbenga, but Dimeji, too — the body he has reincarnated in.

“all too pleasant” is about a father’s strained relationship with his son. Jesutomisin Ipinmoye examines generational trauma and masculinity. He presents, with keen attention, men’s grapple with grief and how unchecked emotional imbalances can create a chasm between progenitor and offspring.

There is an ongoing preoccupation with blood: Kelly in “all too pleasant” graduates from “nibbling the inside corner of his lips relentlessly” to stilling a racing mind “with a blade”. Dimeji, too, in “this space should have been left blank” picks up a blade “and lets it sing across his skin”. And in “belle full” blood ‘calls out’ to Seyi. Redolent of the atmosphere in Pemi Aguda’s Writivism -winning “Caterer, Caterer”, “belle full”, a story about a young man who treads peculiar paths to sate overbearing hunger, takes a chilling and surprising turn.

EXPERIMENTALIST LITERATURE AND ITS MANY WONDERS

In How to Get Rid of Ants, Ipinmoye twists and turns, bending syntax and genre as he pleases. It is a pleasure to read. This is evident in“application”, where a story is told entirely through an online curse form. The story is one not alien to us — that of a cheating husband and his begrudged wife. However, its power lies in its form; in the way Ipinmoye brings a familiar tale to life in a lens that is thrilling, if not bewildering. He doesn’t stop there with his experimentation: “gallant guys of great gusto” is a mixture of play and prose, and it tells the story of Tito, who is caught up in events larger than him, in the underbelly of an organ-trafficking industry.

Perhaps, the most wide-ranging in scope is “synecdoche, lagos!” Its structure is that of a newspaper editorial accompanied by diary notes and interview sessions. It is a story-within-a-story about a now-dead critic on the chase for a review of a ‘bizarre’ new play from an acclaimed playwright.

THE MAKING OF THE ABSURD

In his “The Theatre of the Absurd”, Martin Esslin explains that the Theatre of the Absurd shows the world as an incomprehensible place. The spectators see the happenings on the stage entirely from the outside, without ever understanding the full meaning of these strange patterns of events, as newly arrived visitors might watch life in a country of which they have not yet mastered the language.’

How to Get Rid of Ants shares many a characteristic with the Theatre of the Absurd. In fact, a play demonstrated in one of the stories — “synecdoche, lagos!” — is in that tradition. The collection brims with stories familiar but now imagined in a new lens, absurd lens. Stories that are a cocktail of the melancholy of Samuel Beckett, the socio-political undertones of Arthur Adamov, and Eugène Ionesco’s tragic flavour.

Ipinmoye showcases an acute understanding of the human condition, particularly as it concerns Gen-Z. This is visible in how he does not shy away from the often revolting subject matter of mental illness and its accompanying messiness. It is also seen in the demonstration of stereotypes and police brutality that calls to mind the motivations of the EndSars Protest in the titular story.

The past and the present collapse into one in “solitude!”. An outcast woman is compelled to ‘do a hard thing’ in service to her Ori and Orun. In “husband material”, Bisola, who is deeply dissatisfied with her life, visits a Babalawo in a bid to secure a husband who might, at least, ‘stop the questions’. More than a quest for partnership and the remarkable skill Ipinmoye deploys in its execution — specifically as it concerns characterisation — it is an enquiry into the self: the burdens and ‘expectations’ of being human and the heights a determined woman would go to achieve freedom; not from living but from existing in her form and body.

If you hold on to something tightly enough, it transcends. ‘It becomes larger than life. A small god.’ Ipinmoye presents Morolayo and her children in “spicy!”. They hold on to familial ties and habits amidst Morolayo’s dwindling health. The reader is enamoured with the depiction of the power routines held in shaping the ties that bind men. In the eponymous story, the sighting of “a line of ants marching above the bathroom door frame”, the crushing weight of black tax and ugly harassment collide into an existential outcry.

In “how to tell a story you have not lived”, an aspiring writer moves to Surulere for an inspiration break in order to write about the lived realities of child street hawkers. The story is in itself a commentary on sensationalism and exploitation, particularly that which has come to be known as poverty porn. The narrator asks: “If other writers could turn tales of suffering and pain into widely celebrated literature, then why couldn’t he?”

“lalubu street, oke ilewo” follows a DHL Attendant on an unremarkable day at work, a day rendered rather mysterious by a box from a never-to-be-seen-again customer. This, like most of the stories in How to Get Rid of Ants, is populated with Nigerianisms that are warm, occasionally funny, and do no small job in rooting the collection in a wholesome sense of place.

MASCULINITY AND THE MANY DIMENSIONS OF LOVE

There is an intimate exploration of fraught father-son relationships in How to Get Rid of Ants. The fathers are absent and disappointing: men who rule their home like dictators, as in “we don’t speak of that”; men who seek perfectionists out of their children in order to cover their own failings, as in “all too pleasant!”; men who mete out abuse with smarting cruelty, as in “good sh!t”.

“good sh!t” brings to the fore a story of four boys, failed by their country and ‘the people who brought them here’, and so, they must now resolve to thieving in order to ‘eat from both hands’.

Ipinmoye interrogates collective trauma and negotiation of identity in “we don’t speak of that”. Arguably the most accomplished in How to Get Rid of Ants, the story follows an unnamed narrator as he longs for a time when his existence was ‘craved and not just tolerable.’ Set in the heat of preparations for his sister’s wedding we learn of their coming-of-age in a stifling home, and the push-and-pull to tuck their trauma into neat little boxes.

LIVING IN LOWERCASE

“Lowercase writing is a way to reject the authority and rigidity associated with traditional grammar”, says Caitlin Jardine, a social media manager at The Guardian. “It fosters an atmosphere of inclusivity and emotional connection”. This is true in the way Ipinmoye ditches the uppercase in his titling, and especially true of the emotionally charged “a little misunderstanding with ice”. Written with urgency and a diary-like intimacy, “a little misunderstanding with ice” examines depression and the complicated feelings accompanying self-harm.

Though riddled with editorial oversights one too many, How to Get Rid of Ants is the makings of a master of the form. Like a diamond glinting from all angles, Jesutomisin Ipinmoye is a talent to watch.

Azubuike Obi is an Igbo storyteller who believes in the transformative power of language. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared online and in print in The Republic, Efiko Magazine, Naira Stories, and elsewhere. He was nominated for Chika Unigwe’s Awele Creative Trust Award and H.G Wells Short Story Competition in 2024, and is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in English Language and Literature.