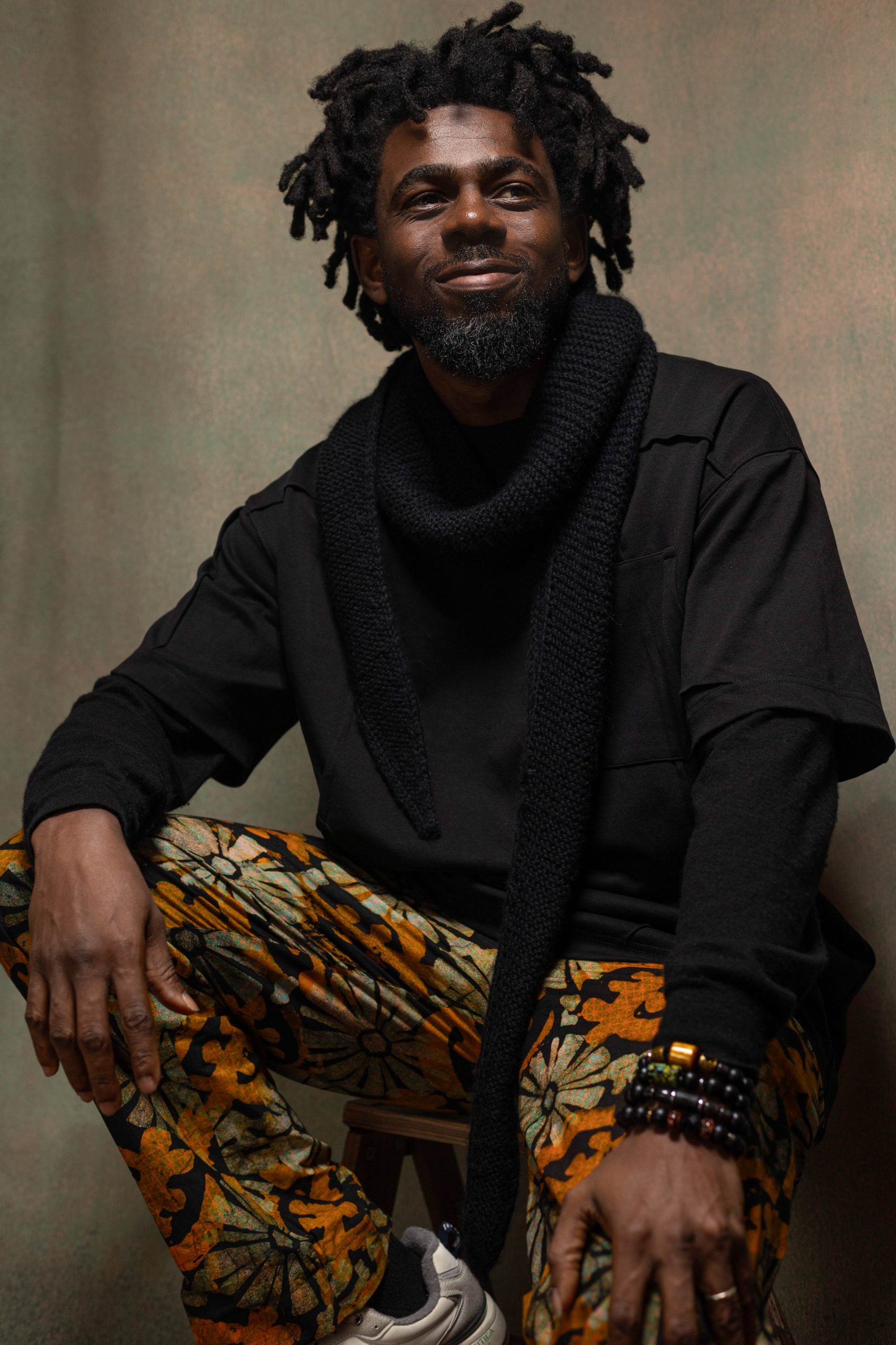

“I want my next film to be the best film, and after that, the next one will be the best”. – Joel Kachi Benson

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

I

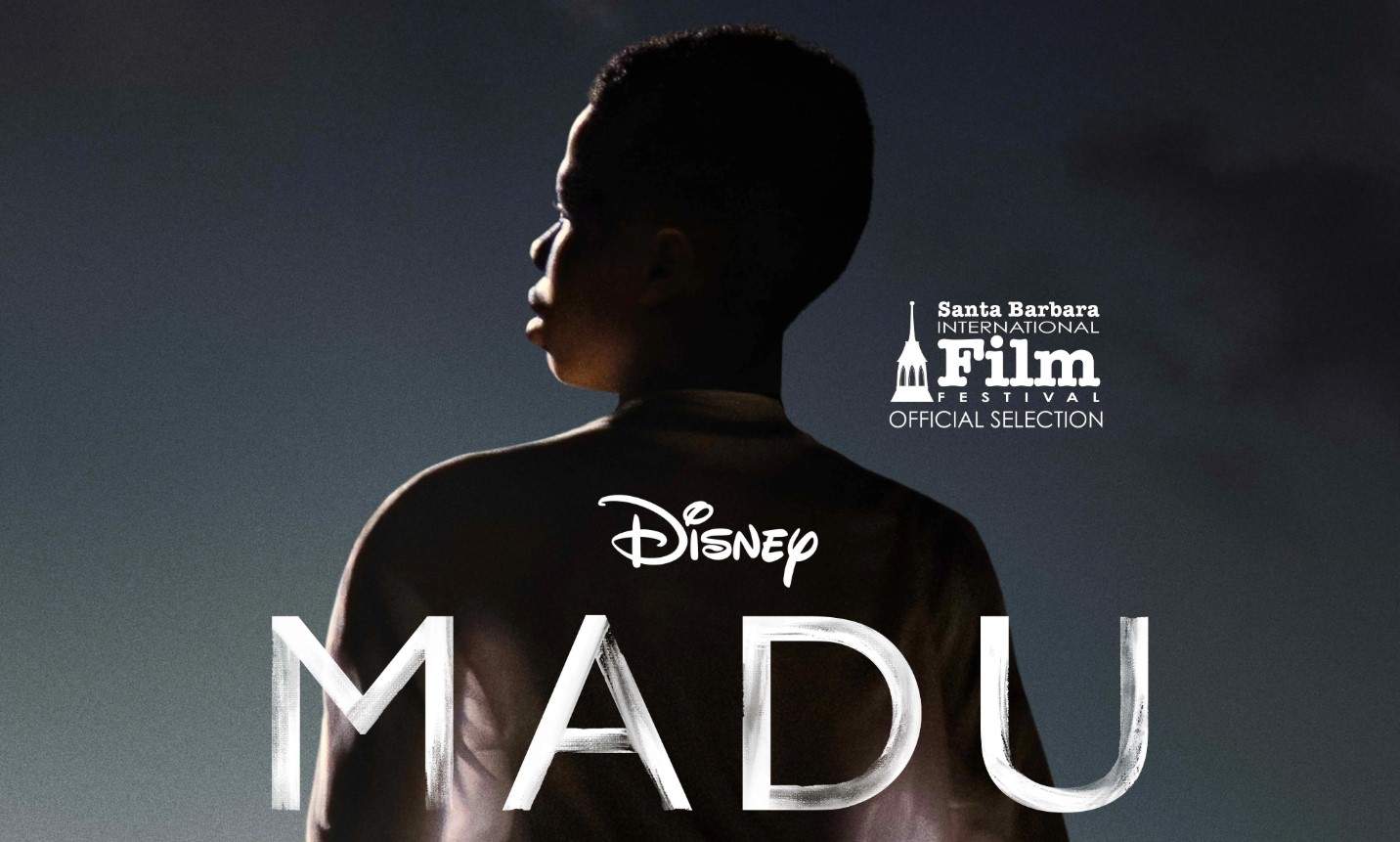

It’s the year 2020. The middle of a global pandemic. Joel Kachi Benson, a young Nigerian documentary filmmaker, is sitting at home when he gets an email. A production company in Los Angeles wants to speak with him about a project; would he be interested in getting on a call? When Benson gets on the call, he’s told a story. There’s a boy in Nigeria who has just gone viral on the internet for dancing ballet in the rain. His name is Anthony Madu, and the Los Angeles company wants to make a film about him.

So, Benson sets out to visit the ballet dancer to get a sense of the story. He meets with Madu and his mother before returning to the Los Angeles company, Hunting Lane Films, simply happy to be part of the child’s story in whatever capacity. He does not expect them to ask him to co-direct the film, but that is exactly what they do.

He soon finds himself working with Matthew Ogens, an Oscar-nominated and Emmy-winning filmmaker, to tell the story of this gifted boy, Anthony Madu, in Madu (2024), a Disney Original Documentary that has now earned two nominations at the 46th Annual News & Documentary Emmy Awards, in the “Outstanding Arts and Culture Documentary” and “Outstanding Direction – Documentary” categories.

This Emmy nomination for direction in a documentary is a first for a Nigerian filmmaker. But Joel Kachi Benson is not new to the art of breaking Nigerian filmmaking records. He’s not just a documentary filmmaker; he is a virtual reality documentary filmmaker, a rarity in these parts.

His very first virtual reality documentary film, In Bakassi (2018), about an orphaned boy living with PTSD in one of the largest camps for internally displaced persons in North-Eastern Nigeria, is widely credited as the first virtual reality documentary by a Nigerian filmmaker. The documentary went on to screen at the 2019 Berlin International Film Festival, marking the first VR documentary by a Nigerian filmmaker at the Berlinale.

His second virtual reality documentary, Daughters of Chibok (2019), about the abduction of the Chibok girls, featured on the Forbes List of Top 50 VR Experiences of 2019 and became the first African film to win “Best VR Immersive Story for Linear Content” at the Venice International Film Festival.

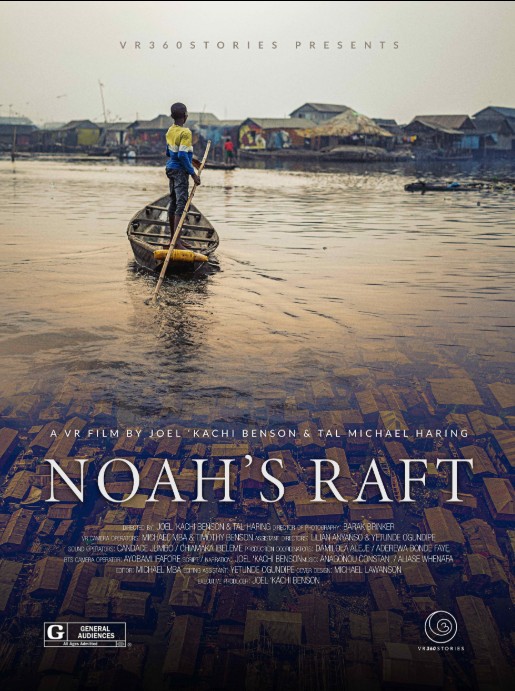

His third VR doc, titled Noah’s Raft (2021), which he co-directed with Tal Michael Haring, is set in Africa’s largest water slum and won the Saint Lucia Award for Best VR Short Film in the Virtual Reality Competition at the 2021 Bogota Short Film Festival.

A Berlinale screening, a Venice win, and Emmy nominations—yet Joel Kachi Benson just wants to make an impact. When I ask him if such huge feats ever get old, he makes it clear that the real win, for him, is the impact these films have.

“I tend to move on from these things very quickly”, he tells me. “I guess it’s usually a case of why did I make the film in the first instance. So, once I understand and figure out why am I making this film, and I achieve that, then every other thing is more like an add-on. When I made In Bakassi, I really just wanted to test out this technology and see how powerful it can be as a tool for storytelling.

“When I tested it out and it worked, and I got the feedback from people that ‘Oh, it felt like I was in an IDP camp; it felt so real for me’, my objective had been accomplished. And then, we were able to also do the social impact side of it which was to help this kid go back to school. So, going to Berlinale and every other place was like, ‘Okay, that’s cool, that’s fine.’

“When we did Daughters of Chibok, I was actually compelled by a friend to send it to Venice, but for me, what was more important was being able to tell the story of these women. Again, using this technology, I wanted to bring people to Chibok. And so, when we applied to Venice and we got the invitation, it was surprising for me, I wasn’t expecting it. Again, being able to play the film on such a huge platform, for me, was ‘Fantastic! We’re able to bring the story back to the global stage.’ I wasn’t expecting to win anything. If there’s anything that has taken me by surprise in recent times, it would be that one.”

Joel Kachi Benson is very grateful, though. After all, these achievements are still very much a form of validation, and they are speaking for him in rooms he might not even be aware of. “It’s humbling, when you think about it”, he says, “because I remember many years ago when I told my friends I wanted to be a documentary filmmaker and everyone thought I was crazy.

“The question was: ‘What’s the model here? How do you make money from it? How do you survive on it?’ And I was like, ‘I don’t know. We’ll figure it out as we go along.’ And here we are, years later, still doing it, happy doing it, doing it the way we want to do it. It’s humbling, and I’m thankful”.

Still, the awards and validation are really not the priority for Joel Kachi Benson. This is not a case of wanting to sound humble or altruistic. It definitely strikes me as the real deal. When he talks, he’s visibly far more excited about being able to remind the world of the Chibok story than he is about winning an award at almighty Venice. He is clearly more interested in what these opportunities can do for the people whose stories he tells than in what they can do for him and his career. And it’s because he understands, from personal experience, which benefits last longer.

“I’ve seen people rise and fall. It’s part of my story. I mean, growing up, things were easy, and then, towards the latter part, it just became really, really tough,” he reflects. “So, in spite of whatever success that I attain, I try as much as possible to stay grounded because these things are very transient. I don’t let myself get carried away with stuff.

“Yeah, you may be the rave of the moment now; it’s probably not going to stay that way for a long time, so just get over it quickly and just move on to the next thing. If you focus on a life of impact and making a difference in people’s lives, I think that’s more lasting, that’s more valuable.”

II

Joel Kachi Benson feels like his life is divided into two parts: before and after he turned eighteen. He discovered filmmaking around the time he turned eighteen, but his life before then was also chequered.

Benson hails from Aba, Abia State, but he was born in Lagos State, where he spent most of his formative years. He attended Pampers Private School, a reputable primary school in Lagos, which he describes as “a very strong foundation”, before moving to the East for secondary school at College of the Immaculate Conception in Enugu State and Umuagbai Secondary School in Abia State.

Of those days, Benson notes: “I was pretty much on the streets, especially in Aba. That gave me some street knowledge. I guess I arrived like a ‘butter’, but by the time the streets were done with me, I had learned a few things. Coming back to Lagos, and then growing up in Ijesha, was also another life of hard knocks. But all of that shapes your perspective.”

After secondary school, while applying to universities, Benson lost his mother. Not only did he have to deal with such a monumental loss at a young age, but he also had to face the harsh reality that he could no longer afford to pay for university.

A kind woman from his church sponsored him to attend computer school, where he learned skills that would later prove helpful in his filmmaking journey. But before he would discover that, he spent a couple of years trying to find his path.

Then, one day, a friend took him—only about eighteen years old at the time—to a film set, where he was immediately fascinated by the director, who was just a few years older than he was.

Joel Kachi Benson began to spend time on sets. He got his hands on a camera and started shooting. A friend acquired an editing computer, and he began editing as well. Unable to afford film school, he taught himself using YouTube and by hanging out with filmmakers. He’d be the first to admit that he stressed them out with his constant questions, and they were probably tired of him. But Benson was hungry for knowledge. “I felt like this is one thing that I’ve picked up,” he says. “This is one thing that I love, and it’s sink or swim.”

In his early days, Benson shot everything, from music videos to weddings and funerals. Gradually, he started to gravitate more towards actual stories. “I found them very inspiring. I think at that time, considering everything I was going through, I needed inspiration, I needed something to motivate me, I needed something to live for.”

On one occasion, he was commissioned by an organisation to produce a series of short films about successful Nigerians. Listening to the stories of these individuals inspired him and made him wonder about others who might need to be inspired, just like he had. “It was just that, I guess, that desire to be inspired, and then now inspire other people.”

When he made his first documentary, it was the story of a woman who ran one of the first private orphanages in Nigeria. The documentary, titled Cry for Mercy, screened at the 2009 BFM International Film Festival in London and led to a scholarship for a fellowship in the United States. And so, it began.

From documentaries about inspirational Nigerians, such as Olu Amoda: A Metallic Journey (2013) and JD Okhai Ojeikere: Master Photographer (2014), to his more popular social impact stories about vulnerable children and women victimised by war and terrorism, Joel Kachi Benson has now made several well-received documentaries that have screened at multiple film festivals, including Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Film Festival, the largest documentary film festival; Cannes XR, which is part of the Cannes Film Market; and, of course, the Berlin and Venice International Film Festivals.

He was listed among the Top 100 Most Influential Africans by New African Magazine in 2019, and among the Most Influential Persons of African Descent by MIPAD in 2021. He also owns a film production and production services company in Lagos, JB Multimedia Studios, where he serves as the Creative Director.

Joel Kachi Benson has acquired several certificates and diplomas, including a diploma in software engineering and a certificate in Information Systems Management from Aptech, India, as well as a certificate in filmmaking from Central Film School, London.

Interestingly, he has also lectured at universities, from the University of Lagos, the Pan Atlantic University in Lagos, and the American University of Nigeria in Adamawa State, to Morgan State University’s School of Global Journalism and Communication in the US, and Biennale College Cinema’s Virtual Reality Program in Venice, Italy. “At the end of the day,” he tells me, “it’s about ‘what knowledge do you have, how well do you have it, how can you share it, how well can you share it?’”

This hunger to continue learning and making an impact is what fuels Joel Kachi Benson and motivates him day to day. “I’m always eager to try new things, learn new things. How do I tell stories differently? How can I make this story more impactful?”

So, when Benson, encouraged by a client and supporter of his work who wanted him on her VR project, discovered virtual reality as a filmmaking tool, he cleared out his accounts, boarded a plane, and went to the United States to train.

For a long time before that trip, he had struggled with how to bring viewers into the world of his documentary subjects, beyond just showing them. During the peak of the Boko Haram crisis, he would travel to Northern Nigeria to make short documentaries commissioned by organisations like the United Nations or the Red Cross, and he was shocked by the sheer level of suffering he saw, especially among the women and children, the biggest victims.

When he returned to Lagos, he found it difficult to describe what he had witnessed. “Yeah, you’ve captured it on video,” he says, “but you’re like, ‘I wish I could take these people there [to] see what I’m talking about.”

So, when he wore a VR headset for the first time during his training in the US, it quite literally changed his game, just as his client had promised him. “Believe me, Vivian, I forgot about this woman’s project,’ he tells me. I laugh, but he’s being very serious. ‘I kid you not. I came back to Nigeria, I started making In Bakassi before I remembered why I even went to America to get the training.”

Of course, making In Bakassi was not easy. Being a pioneer is hard, especially without a framework or a point of reference. But when I ask him how he was able to pull it off, Benson does not dwell on the difficulty. His answer is simple: “I just go and I do it.”

He does acknowledge that it became easier with subsequent films, having created the framework for himself and trained his own team in VR technology. Shooting in volatile areas, like Chibok, became the hard part, but even that would not stop him from doing what needed to be done to make the impact that he wants his films to have. “My work is at the intersection of storytelling and social impact,” he explains. “In making these stories, I wanted to go beyond empathy. I wanted to move people from empathy to action.”

And he’s doing just that. He’s had people reaching out after watching his films, eager to help. Through In Bakassi, Benson’s team was able to help the young boy who was the subject of the documentary go to school. Through Daughters of Chibok, they were able to get support for some of the Chibok mothers to aid their farm work and their children’s education, in addition to a client and viewer facilitating the provision of solar home systems for about 120 Chibok mothers so that their children could extend their reading hours after dark.

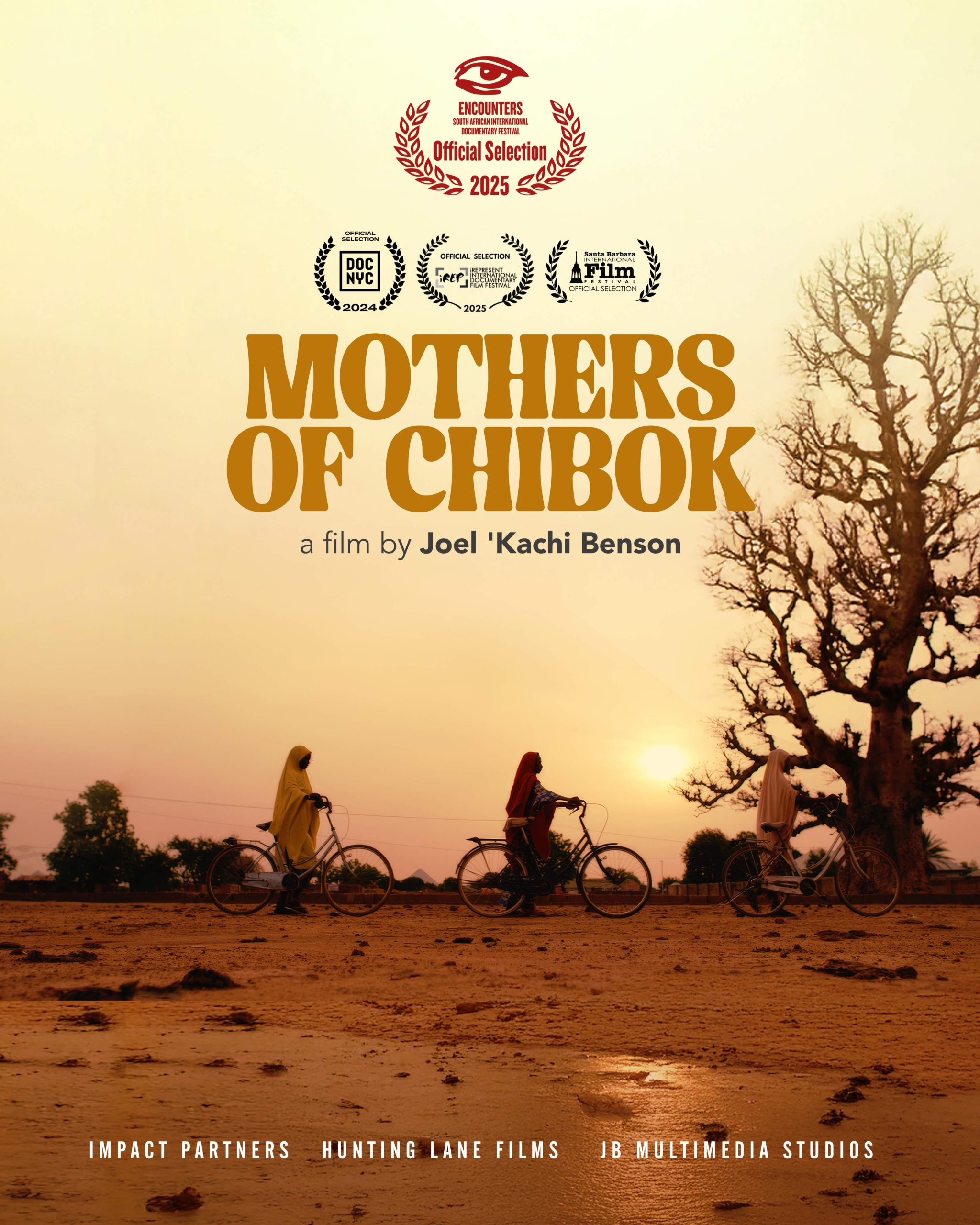

With Mothers of Chibok, his latest film and a sequel to Daughters of Chibok, Benson’s team plans to organise training on agricultural practices to help the women improve and increase their yield, as well as process their products and sell them at a fair market price so that they can afford to put their children through school with minimal stress.

“These are the reasons why we do this thing,” he emphasises. “You put a smile on someone’s face, you do what you can to make a difference in a community. That’s the gratification. That’s the reward. Everything else is peripheral, really. It’s just icing on the cake”.

III

Madu is closer to Joel Kachi Benson’s earlier documentaries in that, first of all, it’s not a virtual reality documentary, and also in the sense that its subject is an inspirational person who is specially gifted. But it’s also very different from any of his documentaries. It is a Disney Original Documentary, and it was his first time co-directing.

“When you’re working with a big studio like Disney, and you’re telling this kind of story, there’s layers and layers of approvals and conversations that need to be had as you’re shaping the story,” he explains. “A lot of the time, I was doing a lot of listening. All those conversations; it was very interesting for me. It was like going to school. My co-director would be talking, obviously he had a lot more experience than myself, and I’d do a lot of listening, just soaking in and sponging in”.

A man who loves to learn as much as he loves to make documentaries, Benson took the opportunity to learn, fully aware that “there are not very many documentary filmmakers in Nigeria that are doing things at that level.”

“I very quickly got myself out of the euphoria of ‘I’m directing a Disney doc, and really got into learning how things work at that stage, and it was really eye-opening for me,” he says. “Everything that I learned was very instrumental to my next film, which is Mothers of Chibok. But I’m very grateful to the team. The entire Disney team, the producers, Hunting Lane, they were very gracious, very supportive. My co-director, it was my first time co-directing, it was his first time co-directing. So, it was also a learning curve for us. I think that if I could point to a turning point in my career, it would be making the Disney doc.”

I ask him what his biggest takeaway from making Madu was, and he struggles a bit. There were a lot of lessons, from collaboration to how to make a film at that Disney kind of level. But in the end, he decides that the biggest takeaway was how to tell local stories with a global perspective.

“How do you tell a story that captivates someone in Malaysia, or in India, or in Australia? What are the elements of your local story that you could weave to now give it a global perspective and a global appeal?”

That is undoubtedly an invaluable lesson, especially for him as a filmmaker who cares so deeply about Nigerian stories. “I’m a Nigerian documentary filmmaker. I live and I work in Nigeria. I’ve chosen to be in Nigeria because I feel like that is where my stories are, that is where I can make the most impact and difference with my work as a social impact storyteller”.

But it is also an important lesson for him as a filmmaker who gets more institutional support from outside his country. “The biggest challenge that we have as documentary filmmakers in Nigeria, or even filmmakers, period, is just that institutional support. My funding comes from outside of Nigeria. And I think that it could be better. It would be better if I got support from Nigeria. I’m fortunate to be able to have those opportunities outside of the country, but what about those who don’t?”

It is particularly concerning that despite being the first Nigerian to make a VR film and the first African to win an award at the Venice International Film Festival for virtual reality storytelling, Joel Kachi Benson has not received any institutional support to continue making VR films in Nigeria. He doesn’t dwell on it, though. “This is not one of those interviews where I want to just rant, but I think that we can do better for ourselves. I think we must do better,” he says, and he leaves it at that.

I take the opportunity to bring up the challenge of distribution. Disney+ is available in only a handful of African countries, mostly North African countries but also South Africa. It is not available in Nigeria, home country to Joel Kachi Benson and Anthony Madu. Benson is aware of this and commits to having a conversation with the powers that be.“There is the economic dynamics”, he reminds me. “When the country is not in the right shape, it affects everything. But that doesn’t mean that if you tell a Nigerian story, Nigerians in Nigeria shouldn’t be able to have access to it. So there has to be a middle point”.

IV

Other than impact, does Joel Kachi Benson have any particular goal that he would like to achieve in his career as a documentary filmmaker? “I want my next film to be the best film,” he answers. “The next film will be the best, and after that, the next one will be the best.”

He’s speaking to me from Oxford, England, where Daughters of Chibok and Mothers of Chibok have just screened at Rhodes House at the University of Oxford. His next film, about a team of female footballers whom he followed for a season, is already being edited. “It’s an amazing story. It’s going to be very different”, he guarantees.

And there is no reason to doubt him. Versatile and impact-driven, with a proven record, it is clear that Joel Kachi Benson will always make films that stand out.

*Mothers of Chibok is scheduled for screenings at Encounters South African International Documentary Film Festival in Cape Town on 21st June, 2025 and in Johannesburg on 28th June, 20255.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on Twitter @Nneka_Viv