Mothers of Chibok is a revelation that filmmakers at their best might not fix history, but may prevent it from being buried.

By Frank Njugi

Sequels are essential renderings in art. A story carried forward is a story pressed against time, context, and consequence. Its relevance widens by accumulation, by what history insists on adding. This is rarer still if a sequel is a documentary, a form that, in much of previous Africa, was treated as peripheral. Now it has gained ground, as a genre of reckoning, as African filmmakers turn deliberately toward the gravity of our own lived realities.

Joel ‘Kachi Benson, the Nigerian documentary filmmaker and virtual reality creator, who in 2025 carved his name into history as the first Nigerian to win an Emmy Award in the Outstanding Arts and Culture Documentary category, has in his work consistently asked what it means to look closely and to keep looking further.

In 2019, his short film, Daughters of Chibok, used virtual reality to collapse distance, placing the viewer inside the aftermath of the Chibok schoolgirls’ kidnapping. As Creative Director of VR360 Stories in Lagos, Benson remained invested in immersive forms as a way of insisting on presence.

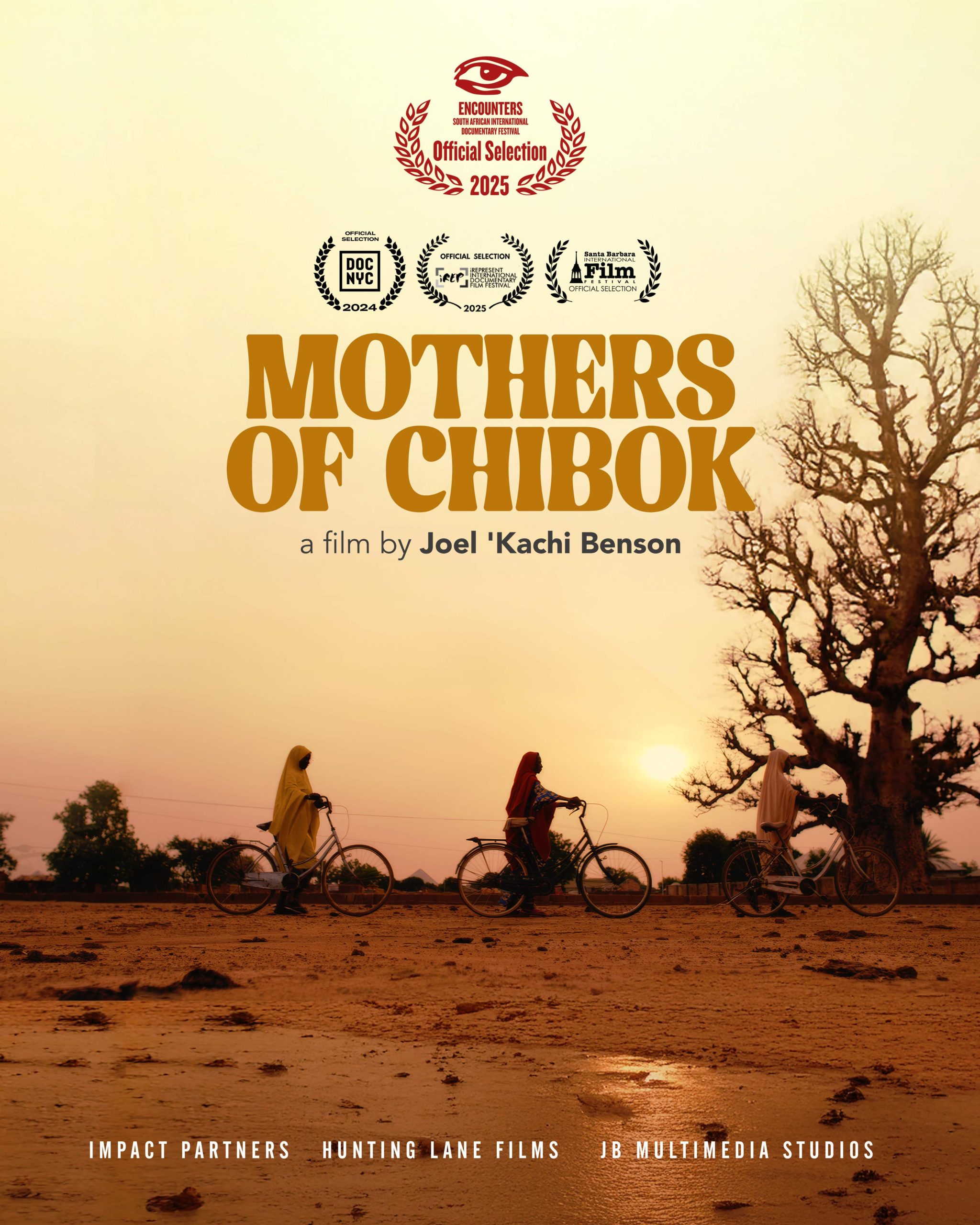

More recently, he returned with a sequel, this time titled Mothersof Chibok, a documentary that premiered at the 2024 DOC NYC. In the documentary, ten years after the kidnappings, Benson goes back to Chibok, this time focusing on the women who remained, those who carried the grief daily.

Benson structures Mothers of Chibok around work, real daily work, the kind that stains the hands and orders the day. His camera moves with the women through planting seasons and prayer cycles, through conversations, and through silences thick enough to feel meteorological. The threat is always overhead, like the rain they await in Chibok that may or may not fall.

What’s remarkable is how Mothers of Chibok refuses to casually frame these casual routines. Farming, feeding, tending to their children, register as small rebellions against erasure that the kidnappings threatened. Even grief, when it pauses, has a texture because when the women speak of the girls who were taken, the film settles into that space within which only hope is portrayed as surviving because there is no alternative.

If cinema is often praised as a machine for memory, the documentary is always where that machinery shows its gears. Benson understands this, but doesn’t overstate it. He lets testimony do the heavy lifting, constructing an archive of pain. Narrative cinema can mythologise, but documentary bears witness without embalming. Here, it seems memory is collective not because we are told it is such, but because it is built from voices that repeat the same ache.

Out of the chorus, individual lives emerge with clarity. A woman named Lydia still waits for her sister Aisha, hope intact. Yana holds tight to the memory of her daughter Rifkatu. And then there is Mariam, a returned captive, raising a son whose existence carries both love and social stigma.

Her desire to continue her education while being separated from her child exposes the film’s cruellest paradox, which is that survival demands forward motion, but the trauma pulls backwards. Lesser films might frame the child as a symbol of violence. But Benson’s doesn’t. His camera, like Mariam herself, recognises the boy as a blessing. Complicated, yes. In this recognition, the film finds a radical gesture, which is the refusal to let suffering have the final word.

In 2014, when Boko Haram abducted 276 schoolgirls from Chibok, the world convulsed in a familiar rhythm of shock and outrage. For a brief moment, the world leaned in. And then, as it so often does, attention drifted. By the following year, the tragedy had slipped into the background noise of national trauma. Life resumed its imitation of normalcy. But Mothers of Chibok puncture the illusion.

The film insists, relentlessly, that for the families left behind, time did not heal but stalled. The film understands limbo as a condition, as days are structured around waiting, seasons measured by harvests that may or may not come, and hope is sustained not because it is rewarded but because abandoning it would be a second loss.

What Benson captures so acutely is the cruelty of that waiting. The film lingers in moments most cinema would cut away from. Maybe to show the ‘suspension’ of a community as the women live inside an extended present, with routine becoming a coping mechanism rather than a comfort. Yes, by refusing narrative payoff, the documentary mirrors the emotional reality of its subjects. Nothing arrives. Nothing concludes.

In a world obsessed with saviours and solutions, Mothers of Chibok makes a case for a different kind of heroism. There are no rescues here, no triumphant arcs. Instead, there is the filmmaker as a witness and as a custodian of memory. Benson seems to be a storyteller who understands that remembrance itself is a form of resistance.

Mothers of Chibok is a revelation that filmmakers, at their best, might not fix history but may prevent it from being buried. In the absence of miracles, they offer attention. And sometimes, as this film proves, attention is the most radical act available.

Frank Njugi, an award-winning Kenyan Writer, Culture journalist, and Critic, has written on the East African and African culture scene for platforms such as Debunk Media, Republic Journal, Sinema Focus, Culture Africa, Drummr Africa, The Elephant, Wakilisha Africa, The Moveee, Africa in Dialogue, Afrocritik, and others.