In I Cry At The Feet of My Other Body, Enesi demonstrates not only an awareness of women’s struggles but also an attentiveness to the language necessary to render those grim realities on the page.

By Evidence Egwuono Adjarho

Agency and femininity are often framed as mutually exclusive, and this is hardly a novel argument. For centuries, societies have imposed restrictive codes of conduct on women, shaping their lives according to an unwritten handbook of expectations. To be considered morally upright, a woman must adhere to these rules with near-religious devotion.

Among the most enduring of these is the denial of agency, especially over her body. Within this patriarchal framework, a woman exists primarily as a vessel for procreation. Her body belongs not to her but to the community. Failure to fulfill this “role” invites condemnation, while any attempt to reclaim bodily autonomy often provokes slut-shaming and verbal assault.

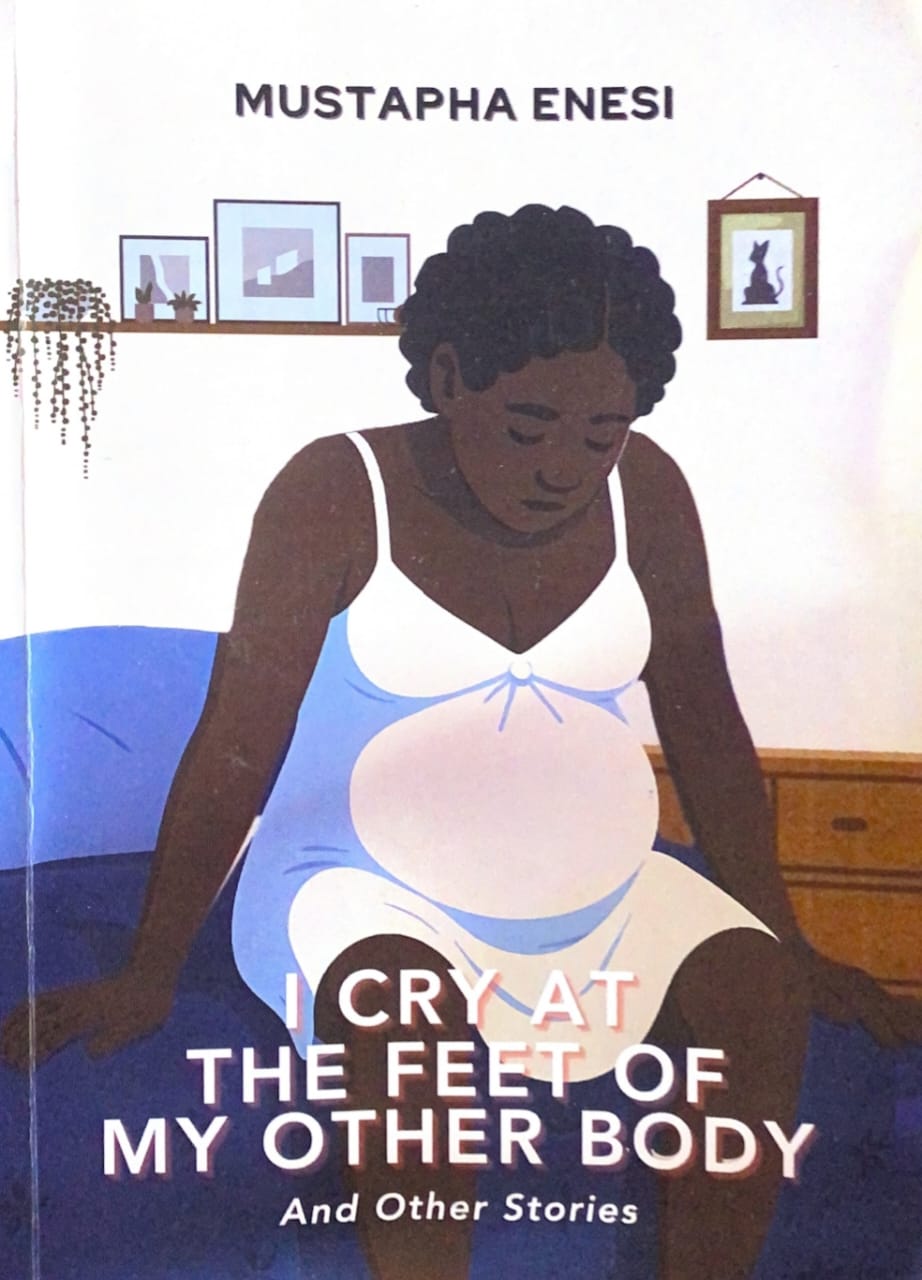

Mustapha Enesi’s I Cry At The Feet of My Other Body brings this tension to the forefront. Across its thirteen short stories, the collection repeatedly centres the woman, foregrounding questions of agency and femininity such as these: What does it mean to exist as a woman in a society that objectifies before it recognises individuality? Where do personal desires intersect—or clash—with communal expectations? What happens when a woman asserts herself? And can autonomy ever exist without backlash? Enesi does not answer these questions in abstraction. Rather, he dramatises them through the lived realities of his female characters as each grapples with a hostile environment.

I Cry At The Feet of My Other Body reveals itself to readers as a non-linear, occasionally esoteric collection. Yet beneath this surface lies a clear-eyed engagement with pressing social issues. The opening story, “Shoes” (the shortest piece in the collection) sets the tone. Told in a detached second-person voice, the story centres on a mother chastising her rebellious daughter, forbidding her from wearing her beloved blue shoes to Okey’s shop.

The syntax is complex, fraught with long sentences made of unending commas and semi-colons, but the meaning emerges as the story progresses. Perhaps, the blue shoes exacerbate her visibility; it then becomes a metaphor: women must deny themselves the things they love, suppress their individuality, and live in perpetual self-censorship in order to survive society’s predatory gaze, which is represented in the story as ‘Yaba boys’.

This forced denial of choice recurs throughout I Cry At The Feet of My Other Body. In “Safety Pins Are Good Omen”, Nene is tormented by her mother-in-law for her inability to bear children, as if repeated miscarriages were her deliberate failings. Through Nene, the story asks important questions on the emotional cost of the woman’s reduction to reproductive function: “What emotional turmoil have women endured must to become mothers, to bear a child, to make their bodies do the one thing it was designed to do?”

Nene internalises this scrutiny as “five rules to help me bring my baby safely into the world”. Even during pregnancy, she is subjected to cruel expectations: cooking tirelessly through pain and performing sexually for her husband to remain desirable despite exhaustion.

Harassment, in its different forms, is a persistent thread linking many short stories in I Cry At The Feet of My Other Body. In “Kesandu”, the titular character is introduced in a most unsettling way: “black and yellow teeth flashing…stabbing her bouncy breasts into the faces of people…clapping her hands at invisible flies”. Yet flashbacks reveal her traumatic past: Kesandu was sexually abused by her father and blamed by her mother for “flaunting yourself all over the house”.

Unable to live with the child born of incest, she flees home and later loses her will to live. In “Doctors from Lagos,” Simbi is verbally harassed simply “because of her effortless poise, elegant voice, and attitude”. Similarly, “Naked” speaks to the hostile treatment another woman, Amina, experiences when she decides to stand for herself. Enesi paints, through these stories, a grim portrait of how harassment infiltrates every sphere of a woman’s existence, shaping how she moves, dresses, and even thinks.

While I Cry At The Feet of My Other Body chronicles these unpleasant but realistic experiences, scattered throughout are also moments of reclamation of agency. Nene’s decision to remove her womb after repeated miscarriages in “Safety Pins Are Good Omen” is a refusal to let her body continue to follow the dictates of societal scripts. Kesandu’s choice to flee home while abandoning her child is also a refusal to continue in a cycle of abuse. In another story, namely “One Good Thing”, Mrs. Silifa permits herself to “experience the beauty of orgasms” decades after her unfaithful husband’s death, reclaiming sexual pleasure long denied to her.

Beyond gender, I Cry At The Feet of My Other Body also gestures toward broader systemic failures in Nigeria. “Doctors from Lagos” critiques the collapse of healthcare, recounting the painful experience of Simbi, who watches helplessly as Ojo, an orphan boy she hoped to save, dies from a lack of access to healthcare. “Hanging Prayers” offers a biting look at the bureaucratic absurdities of visa applications in Nigeria.

A noteworthy stylistic choice in I Cry At The Feet of My Other Body is Enesi’s use of recurring names. Many female characters share names—Nene, Oyiza, Obiageli. This may be an onomastic strategy to signal the universality of women’s experiences. The repetition suggests that the plight of one woman closely mirrors that of another. Yet, this device is questionable. Because short stories afford less space for character development, repeating names can blur distinctions between stories, thereby making it difficult for readers to track individual stories as well as their characters.

Yet, importantly, it must be said that Mustapha Enesi is a writer who understands words and how to manoeuvre them into sentences to achieve the hallmark of creativity. Sometimes, the sentences are short, but they deliver with impact nonetheless.

Consider, for instance, the scene in “One Good Thing” when Mrs. Silifa discovers her boyfriend’s infidelity: “Ben stands up and walks to the kitchen to excuse himself. He brushes his shoulders against Eniola. And he shifts. And she shifts. And Mrs. Silifa gasps”. The brevity of the sentences mirrors the shock of revelation and captures betrayal more through rhythm and syntactic choice than explanation. It is in such moments that Enesi’s craftsmanship is undeniable.

In I Cry At The Feet of My Other Body, Enesi demonstrates not only an awareness of women’s struggles but also an attentiveness to the language necessary to render those grim realities on the page.

Evidence Egwuono Adjarho is a dynamic and evolving creative with a flair for literature and the arts. She finds joy in reading and writing, and often spends her free time observing the world around her. Her interests span a wide range of artistic expressions, with a particular focus on storytelling in its many forms including photography.