If Finding Nina were simply the romance drama that it is so focused on being, it would still be a bad romance drama, but at least it would not need to pretend to be the cinematic saviour of Northern Nigeria.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

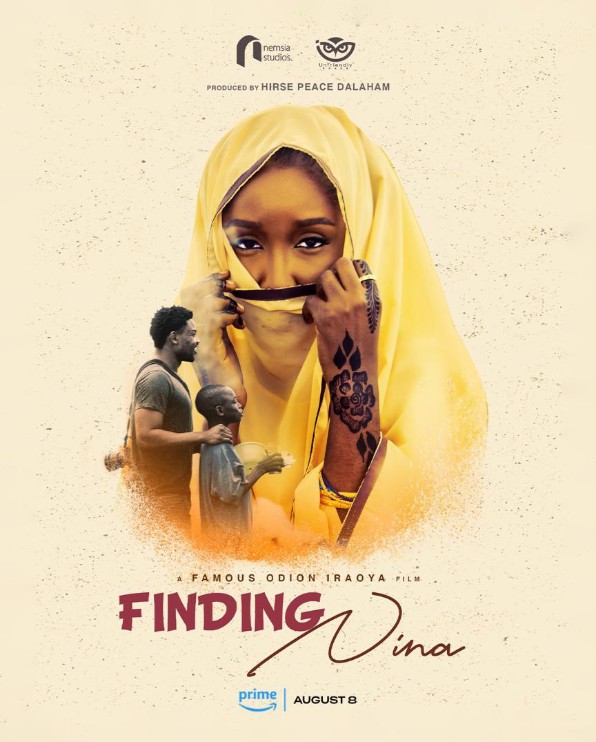

It is a grand cause to attempt to employ cinema as a means towards reframing prevailing narratives about a place or people, especially places and people who tend to be perceived in a negative light. Nemsia Studios’ latest direct-to-Prime release, Finding Nina (2025), takes on this challenge on behalf of Northern Nigeria. But with no passion, no fidelity, and a flavourless story anchoring the vision, if there can be said to be one, the result is an uninspiring, incoherent mess of an attempt.

And it is surprising because there is hardly a better way to pull off such a project than through the lens of a photographer with a connection to the focus community, which is what Finding Nina, directed by Famous Odion Iraoya, adopts.

We’ll get around to the titular character, but the lead role in Finding Nina is that of a professional photographer who spent a good part of his childhood in the Northern village where he was born. Ibrahim Jammal plays Jabir, JB to his friends, a photographer who now lives and works in Lagos.

The synopsis on Prime Video refers to him as a renowned photographer, but in the film’s reality, he’s just a too-big-for-his-britches freelancer who hangs his photographs in a gallery owned by his friend, Raiya (Tomi Ojo), who happens to be romantically invested in him.

Anyway, when Raiya writes a favourable review for a stereotypical portrait from another photographer titled “Window to the North”, JB has a lot to say about the need to change the perspectives that people have about the North. So, Raiya commissions him to put his talent where his mouth is. And even though he’s been rejecting calls from his uncle (Paul Sambo) inviting him to visit home, JB sets out to his hometown to capture the goodness and allure of the North.

Or something like that. JB barely takes one memorable picture before he re-encounters Nina (Ijapari Ben-Hirki), a childhood friend he once took a portrait of with his father’s (Rikadawa Rabiu Mohammed) camera. From thereon, the mission gets derailed, both his and the film’s. With the help of Abdul (Ahmad Isah), a young, street-wise Almajiri boy, he goes in search of Nina, a remarkably brief search that raises unanswered questions. Like, why is Finding Nina the title of this film? And who, even, is Nina?

For someone whose existence is supposedly fundamental to the film, we have no idea who Nina is beyond just a subject of one of JB’s earliest pictures. When we first meet Nina, she is still a child, and even though it’s the scene where a pre-teen JB takes that all-important portrait, she is introduced with near disinterest. When she unexpectedly reappears as an adult woman, it’s also with disinterest. JB’s camera apparently captures her, but the film’s cameras do not. In fact, the first time we hear her name in the film is when JB starts to look for her.

Who is Nina as a character in her own right? We will never know. Why does she matter so much that everything else in JB’s life takes a backseat because he thinks he might have seen her? Why does she suddenly live in his dreams? JB has an answer: They have “a special connection”. When those words roll off his tongue in the film’s second act, it is a laughable moment because it means nothing. And neither the circumstance nor the character (not even the actor, himself) is the least bit convincing.

Quite frankly, too much in Finding Nina is unconvincing. When JB invites Nina back to Lagos with him, you wonder where that came from. When he tells an elderly man that he is not ready and he is not certain, you cannot be sure what he is supposed to be ready for or certain about. And when he goes on a rant to Abdul about Raiya, it is a mind-boggling outburst that is inconsistent with everything that has happened up until that moment.

Even worse, he throws in a bit of sexism. “Women are evil… Forget women, they have no use”, says the man who has been clearly uninterested in Raiya and is now upset that she may be moving on, even though he has just asked another woman to return to Lagos with him. Then, he follows up with a “big reveal” about his parents’ past that is meant to serve as a backstory that explains his attitude, but is grossly underexplored, has no direct link with the conflict that triggers its revelation, and has no real impact on the story.

There is a more sensible aspect of JB’s backstory that Finding Nina could and should have relied heavily on, which, interestingly, would have worked for Nina’s character as well. Over and over again, the film mentions a riot that occurred when JB and Nina were children, hinting at the loss and pain that trailed the riots. Despite the apparent effects on the film’s characters, Finding Nina sidesteps the riots. We are provided with no details, as if we’re supposed to come into the film fully apprised of the facts of the riots.

So, where do we find these facts? Perhaps, we are expected to look beyond the film. The opening sequence in Finding Nina, where we meet young JB, is set in May 1999. We assume that the riots took place not very long after. In real-life Nigerian history, Nigeria ushered in her fourth republic in May 1999, and inter-ethnic riots broke out in Kano State around July 1999.

Presumably, either or both of these events may be related to the events in Finding Nina. But this is another thing we will never know for sure. And the silence on the subject is a missed opportunity that could have lent Finding Nina valuable political or historical relevance.

Yet, the biggest sin of Finding Nina is that it fails woefully in the actual mission that it seemingly set out to accomplish. If Finding Nina were simply the romance drama that it is so focused on being, it would still be a bad romance drama populated with poor performances and severely lacking in chemistry, but at least it would not need to pretend to be the cinematic saviour of Northern Nigeria.

Finding Nina is not the first film with the vision to combat negative portrayals of Nigeria’s northern regions. Take, for instance, Up North (2018). Regardless of what one may feel about the Tope Oshin-directed film, the case that it makes for its focus region is undeniable. That film is practically a feature-length commercial for Northern Nigeria. Even Desmond Ovbiagele’s The Milkmaid (2020), a film about terrorism and violent conflict in the North, understands the value of presenting an alternative narrative to counter a less favourable one. And so, The Milkmaid presents a stunning, cinematic picture of the North, with a passionate tale of resilience and agency.

Finding Nina, on the other hand, offers no narrative. What exactly is the story that the film’s apparently talented photographer intends to tell with his photographs? What is the film itself trying to say about Northern Nigeria? What does it want to show you to challenge whatever preconceptions you might have? Finding Nina does not provide tangible answers, so you come out of the film seeing nothing different and learning nothing new about the North.

Even in terms of just capturing locations and landscapes, Finding Nina does nothing to stand out. “I and Abdul have been to all the exotic places,” JB tells Nina, and you wonder if you missed the scenes where all those exotic places featured.

Besides, whatever little publicity Finding Nina does for Northern Nigeria, the film throws it away with a severely unnecessary third act scene that might have been intended to provide a balance in the story but ends up reinforcing negative stereotypes around insecurity in the North.

Like its lead character, Finding Nina is itself confused and manifestly uncertain about what it wants to achieve. It does have several operable ideas. Promotional material for Northern Nigeria. A journey of self-discovery. A love triangle romance. A second-chance romance. A friends-to-lovers romance. Even a mentor-mentee bromance. But it develops none of these properly, neither does it have the sleekness to mine them in any interesting way. Ultimately, it all feels aimless and drab—a real snoozefest.

It’s truly fascinating that a film about photography, tourism, and reconnection, with four screenwriters credited, can end up being so soulless and lacking in discoveries. Well, at least, I learned a Hausa proverb from this film, and I might as well put it to good use. “A chicken ignorantly sleeps hungry while lying on a bag of food”. Finding Nina died of hunger, and its deathbed was none other than a bag of food.

Rating: 1.3/5

*Finding Nina is streaming on Prime Video.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time watching, reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv