Nigeria has a serious class problem. As with all such societies, the controlling oligarchy is only actively involved in pursuing self-centred policies.

By Chimezie Chika

I

Let us begin with a familiar story. Nnamdi grew up in a big house in Ikoyi, Lagos, owned by his dad, who is the CEO/MD of a 55-year-old family-owned company. His mum is a member of the House of Representatives, in her second tenure. Between June and August every year, and sometimes in December, the family goes on vacation to Europe or America, or any other place around the world that welcomes bankable tourists.

Nnamdi’s parents established an investment account for him as soon as he was born, which is expected to grow to millions of dollars by the time he clocks eighteen. Nnamdi started driving at puberty. He takes whatever car he likes from the luxury fleet in his parents’ garage. In his earlier years, he attended a British school.

Within Nigeria, his visits outside Lagos are either to Abuja or to his village in Anambra, where his father has another big 30-room mansion. Nnamdi has never seen a bad road in his life except on the internet or in the news (at least not in the sense in which most of his fellow Nigerians do). Nnamdi has never known power cuts in his life, except on the internet or the news. Nnamdi’s circle is close.

His friends are the sons and daughters of an industrialist, a real estate mogul, high-ranking politicians, and businessmen with hefty investment portfolios; his uncles and aunts are either wealthy gentrified immigrants in Western countries or the selfsame fathers and mothers of his friends.

After secondary school, Nnamdi insists he wants to further his education at an Ivy League university, and his parents agree too, since that has been their plan all along. He finds the Ivy League school he chose fascinating because of what his cousin Aderonke, who is studying there on scholarship, tells him.

But Nnamdi is an average student and therefore cannot get a scholarship like his brilliant cousin, Aderonke, who herself has a Dad that owns a private university in Nigeria. Nnamdi’s dad subsequently makes a handsome donation to the Ivy League school in millions of dollars, to be used for research purposes and, soon, Nnamdi gains admission into the school to study Business Administration and Management, a course his dad considers fitting for his future role.

Nnamdi takes all these for granted. Nnamdi thinks most people either live like he does or are not that far off. “It can’t be all that bad for Nigerians, is it? Not sure why they always complain”. Nnamdi consequently attends the school, goes through his undergraduate studies as softly as he considers appropriate to his classy tastes.

Upon his return to Lagos, Nnamdi marries Stella, the daughter of his father’s industrialist friend, who had had a gentleman’s agreement with his father that their children would marry each other. Later on, he takes over the family company, struggles sometimes with government policies that affect business; these prove to be scalable hurdles with the right connections and pecuniary support for incumbent politicians in the ruling party, especially during elections.

In his later years, flush with achievement and about to hand over management to his own children, Nnamdi writes a book titled, My Struggle for Success (actually ghostwritten for him). And so and so forth; you get the drift.

II

The hypothetical story above illustrates the reality of a different world, which many Nigerians will only ever be acquainted with through the internet, some society weddings, or through the conduit of glamorous plots in Nollywood movies.

Rarely does an average Nigerian come into direct contact with members of these exotic individuals, who make up one percent of the population or less. This is because their lives have been conditioned in such a way as to insulate them entirely from the rest of the country.

And when such contact happens, the one percent individual is sometimes incredibly confused, unable to understand the motivations and aspirations of his less-privileged countryman.

The fawning and attention which aspirational Nigerians unwittingly accord to the wealthy is worthy of painstaking psychological study. Such attention is not given to any significant virtue other than the reality of their being extremely privileged in a society where most of the rest are severely handicapped economically. But this condition allows for two things to fester: admiration, on the one hand, and hatred, on the other.

The former elicits ambition, which can sometimes throw the moral groundings behind the inordinate pursuit of wealth into stark relief; the latter creates revolutionary anger or exposes the wealth inequalities that have been perpetuated for long in this country, from the inception of the colonial divide-and-rule system to sycophant reward systems that subsequently emerged out of it. But also, in circumspect, both can also be the impulse for crime.

It is all too familiar, as far as this country goes…

III

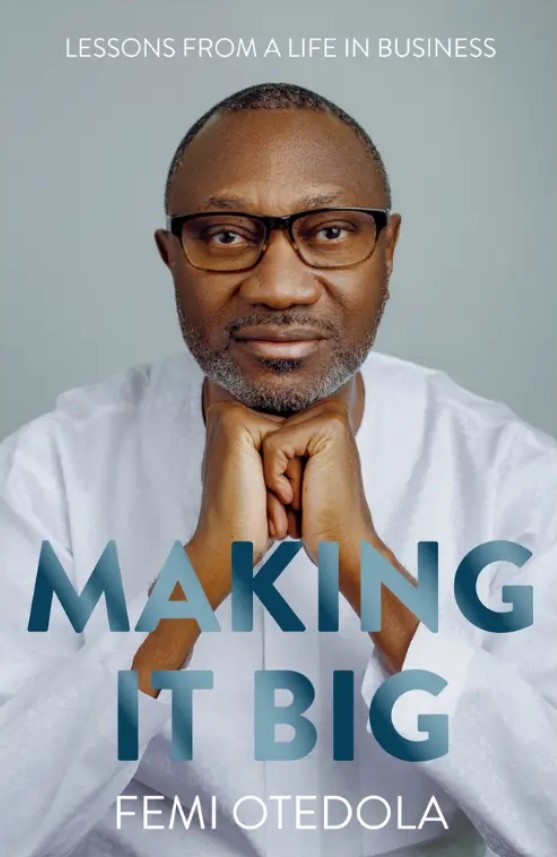

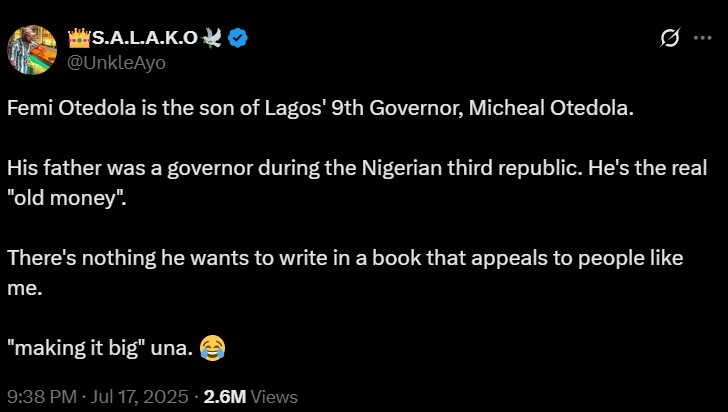

A week ago on X, the seeds of this reflection were sown when a user, who goes by the name of Uncle Ayo, made a series of posts highlighting the problem of a man like Femi Otedola announcing the forthcoming publication of his memoir titled, Making it Big: Lessons from a Life in Business.

In those posts, Uncle Ayo makes a compelling argument that Otedola and the likes of him achieved success, not through hard work alone, but through privilege, access, and leveraging family wealth and connections.

The telling examples he gives trace the deep-seated connections and generational wealth that run through the families of people who occupy strategic positions of influence in all spheres of this country. In light of this, Uncle Ayo accuses the upper class of romanticizing struggle for the benefit of their self-image and their desire to be seen as a generational inspiration to all and sundry.

“No let anybody write book for you oo”, Uncle Ayo writes in pidgin, noting the foolhardiness of a less-privileged Nigerian trying to draw inspiration from people who had never had to struggle for anything most of their lives, people who, by virtue of their birth alone, was always going to be “3000 steps” ahead in the race toward success.

It is easy to understand the motivations behind the added glamour of laundering one’s success story as that of scaling over high walls, defeating insurmountable obstacles, and achieving goals via a road filled with struggles.

For one, it makes for a more riveting tale (there is certainly nothing more boring than a story that is devoid of struggle or any form of pain); and it enhances the image of an individual to that of a heroic persona. This is nothing more than the classic noblesse oblige. In Nigeria or elsewhere, class problems have always resulted from coded class attitudes—that of the rich always paying calculated lip-service to the poor.

The fallout from Uncle Ayo’s indictments seems to have established a remarkable cultural moment in which already existing metaphors are further entrenched into the fabric of social relations to describe the different economic and social states, worlds, and conditions in which Nigerians exist.

The group, labelled “Nepo babies” (after the word Nepotism), are the extremely privileged, trust-fund backed individuals who constitute less than 1% of the Nigerian population and occupy a soft bubble of plenty and ease where the daily struggles of the majority of their countrymen are a far distant tinkling bell; the other group, labelled “Lapo babies” (after the notorious loan sharks, LAPO) conjures up images of unending debt, want, extreme deprivation, illiteracy, and perpetual struggle to make ends meet.

IV

What I would refer to as the Nigerian Social Other is one of the worst states to exist in. In its barest offerings, there is nothing to gain; there is no sign of respite, no comfort, no peace, no way to meet even the most basic needs to sustain life (one wonders whether our governments and their anchors under the acronym HDI).

It is often easy, when one lives a kind of life in which feeding is taken for granted, to forget that there are dozens of millions in this country for whom to do that just once a day is a mammoth struggle. It might sound outlandish even, but this reality stares at us every day in this country outside the insular environments of gated communities.

Wealth disparity in Nigeria is not a matter of frivolity. It is fomented by a negligent government that insidiously apportions rewards through an established nepotistic system. This is why a historical analysis of some of the most important positions in the land in the last 60 to 70 years would show that they mostly rotate among the same closed circle of people, their children, their grandchildren, and their lineages.

The reality of this is that Nigeria has a serious class problem. As with all such societies, the controlling oligarchy is only actively involved in pursuing self-centred policies. The good news is that oligarchies are not completely sustainable in developing societies with geometrically expanding populations unless they find insidious ways to acquire mutative abilities (which many have done successfully, by the way).

Class blindness in Nigeria immensely affects government policies. Instead of investing in education, health, and other indices of human development, what we often see are unattainable white elephants posed strategically to enhance reputations just so far enough as to influence the tribal and religious prejudices that seem to win elections in Nigeria.

The solution to class-motivated wealth disparities is usually social welfare policies. The socialist democracies of Europe diagnosed and understood this problem in the post-WWII years and now enjoy the dividends of the policies that were formulated at that time.

Several tools such as taxation, universal health and educational reliefs, and social security, often help to alleviate these social extremes, for no society will get anywhere with such stark disparity in the comparative comfort of the majority of its citizens and therefore of the country itself, since a country’s being and image is nothing without its people.

V

A few Nepo babies did come at Uncle Ayo for his posts, arguing that some of the wealthy work harder than many of the poor who accuse them of privilege. This is true, in a sense, but it is also true that the hard work of the connected is crowned with access and wealth, so that it becomes easy to achieve goals.

For individuals within the Nigerian Social Other, hard work is not at all a guarantee of success. As many have argued, millions have broken their back with the most grueling hard work and still died without experiencing even the simplest comforts. There is nothing more insensitive, more affirming of privilege than calling the Other lazy.

It highlights the nuances that exist in any straightforward argument regarding the injustice of a system that encourages the ever-widening gap between the rich and the poor. The system conditions the former to achieve with maximum or minimal effort; for the latter, there are no guarantees that any kind of effort—maximal or otherwise—would lead to any kind of success.

The psychological effects of a long-entrenched situation in the province of lack and deprivation are damaging. Studies have shown that the long stay of poverty in the life of an individual leads to anxiety, all kinds of depression, mental illness, emotional instability, violence, and even brain regression.

This is part of the reason why some of the sanest, mentally stable, and sensible people out there are still people from wealthy, or at least comfortable, backgrounds (Why? For the simple fact of the opportunity scale. They are so far high up on the opportunity ladder that their interests are not the mentally draining squabbles of necessity but the bliss of health, well-being, and innovation).

In other words, these kinds of over-wide income disparity we see in Nigeria are too costly in human terms to be allowed. And as I have noted previously, many countries in the West and East have understood this and have moved regulations and policies in the right direction to varying degrees of success.

It is in this sense that the inordinate craze for wealth in Nigeria—especially among the Other in a more overt way, but also for the upper echelon, in a more covert, state-sanctioned way—is detrimental to the country’s moral and social well-being. People want to achieve wealth—not even comfort—by all means.

We have seen its fallout in spikes in ritual killings, greed, and corruption in high and low places, in the Yahoo culture, in the inability of successive governments in this country to achieve meaningful development over long periods.

A society where criminals with questionable sources of income are eulogised and admired for their wealth is headed towards a bleak horizon. A society in which wealth, regardless of moral standing, has more purchase than notions of right and wrong, will have its systems of accountability—if any exist at all—completely eroded.

It is what we have seen with the Nigerian judiciary and other institutions that were mandated with upholding this country’s ethical foundations. Where there are no funerals, vultures become revered citizens.

Chimezie Chika is a staff writer at Afrocritik. His short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Weganda Review, The Republic, Terrain.org, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Fahmidan Journal, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, and Channel Magazine. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture, history, to art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on X @chimeziechika1