Poetry clarifies and enriches our lives because it can make us stop and look closely at a thing.

By Ernest Jésùyẹmí

Poetry is limited. It cannot change the world, and it can’t stop a war. It may laugh sardonically under iron boots, but it cannot topple stinky riggers from thrones; and sharing or writing poems against such horrors only points to something in human nature: we have great, if at times absurd, faith. We are like children who raise broken flutes into the eye of a tsunami, hoping that it would choose kindness. This act of silly defiance says nothing at all about the flutes.

But poetry has its uses. And one of these is its ability to console (“to comfort in mental distress or depression; to alleviate the sorrow of (a person),” says the OED). One of the poems I turn to in times of need is “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry, but many are not as direct in their consolation. In “Storm Fear” by Robert Frost (another poem I turn to), “even the comforting barn grows far away.” I think all good poems have the ability to momentarily stay us against confusion, as Frost also said. But the stay they provide must be got with great difficulty, because it tends to be ambiguous. (Teju Cole once described this as “consolation in complexity.”)

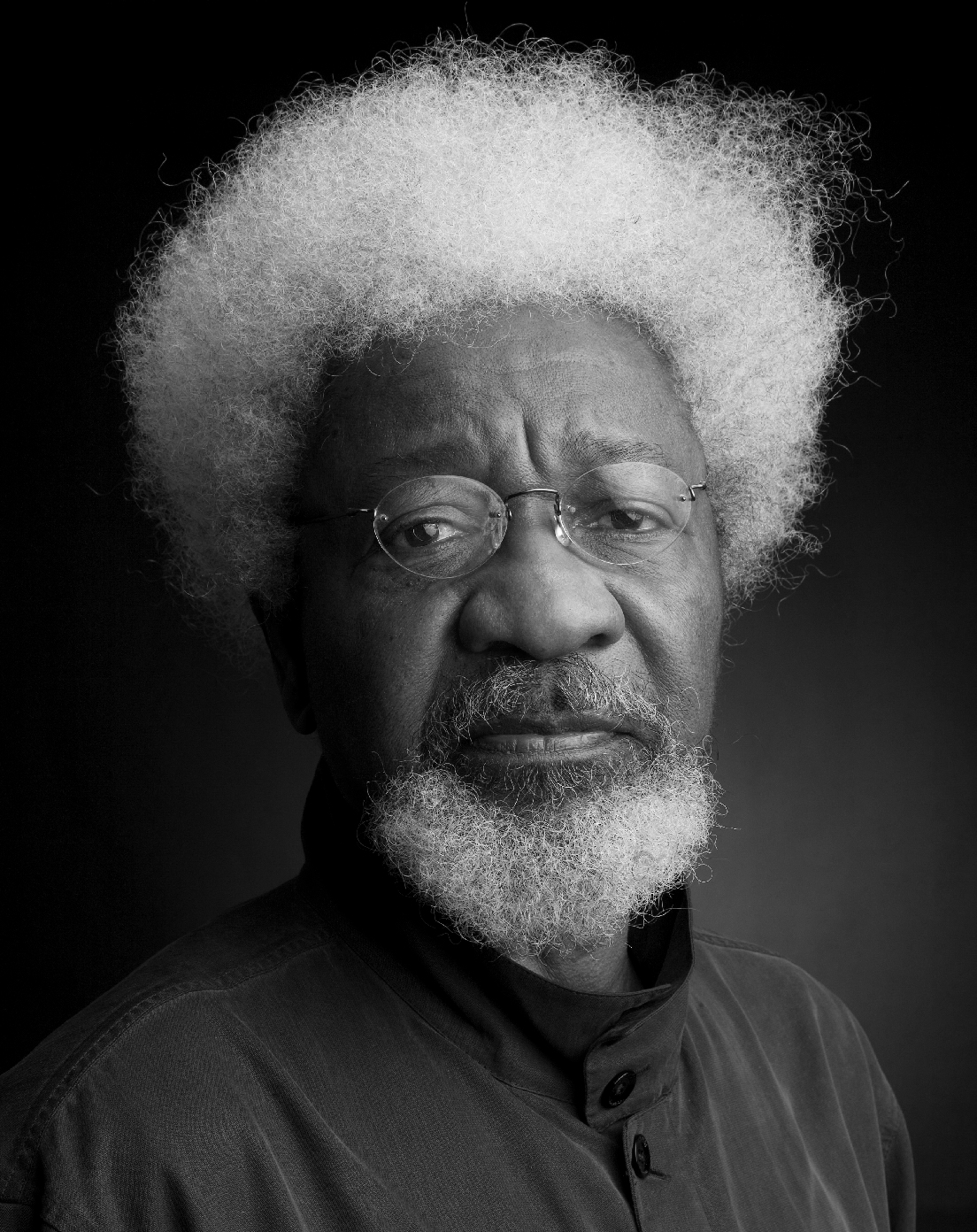

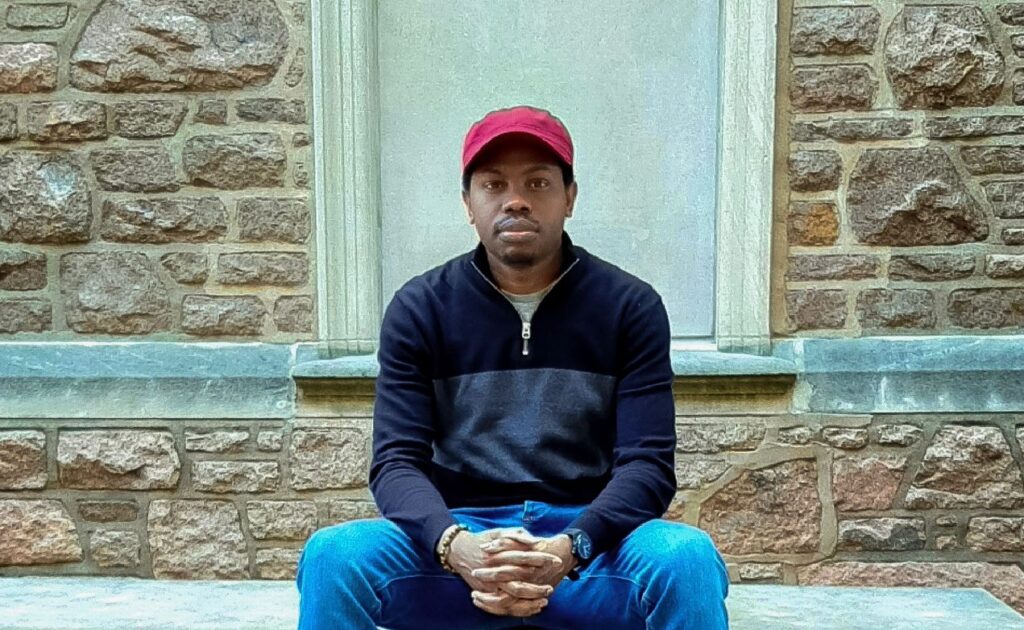

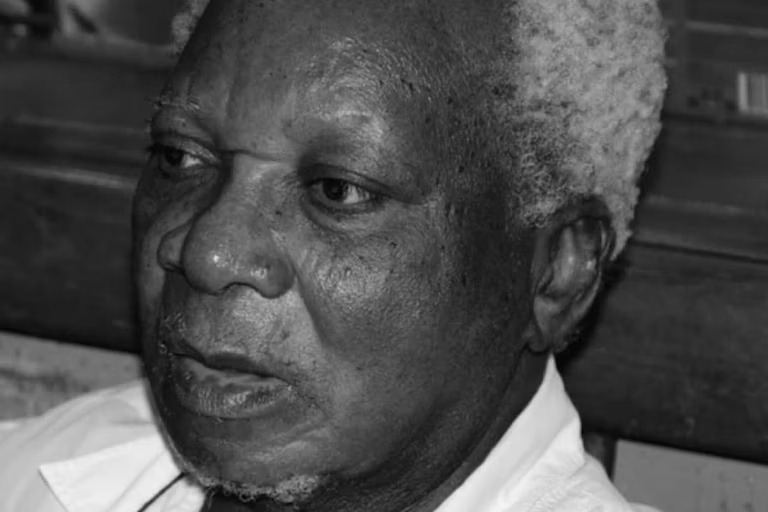

In this piece, I look at three poems—by Wole Soyinka, ‘Gbenga Adeoba, and J. P. Clark-Bekederemo. I think each of the poems in its way help us to bear our fine share of suffering.

I

“Koko Oloro” is brief and makes itself available on first reading. It does not pose the syntactical challenge familiar to those who have engaged with other poems by Wole Soyinka. Culled from “a children’s propitiation chant”, the season of childhood can be gleaned from the lyric, from its tone. Here is the poem in full:

Dolorous kno[t]

Plead for me

Farm or hill

Plead for me

Stream and wind

Take my voice

Home or road

Plead for me

On this shoot, I

Bind your leaves

Stalk and bud

Berries three

On the threshold

Cast my voice

Knot of bitters

Plead for me.

There is, in the voice (if you can hear it), a budding anxiety, a sadness that has not ripened, and a dread that is yet in its infancy. And there is innocence. The anxiety, the sadness, the dread are waiting to break out of the innocence, but they haven’t yet. However, the child is becoming aware, though he may not be able to speak of it as “an awareness,” he is starting to sense that something is not right with the world. He is “on the threshold” of this realisation.

Childhood is a partial experience; we are shielded by the hands of love from the wrecking truths. But here, in this poem, that shield is about to be taken off. The young man is about to begin his journey—alone against the diabolic forces that are at work in time.

Something is now on its way to him (he is beginning to suspect), and there is nothing to protect him from it—whatever it is—when it comes. The anxiety grows inside him; and as his consciousness of the possibility (and the inevitability) of disaster becomes sharper, his anxiety becomes dread. But all of this is not yet come; and, innocent, the child sings as he has been taught to do.

There is something tragic about this, and I think it relates to the futility of propitiation—the fact that we are given tools to live with and truths to live by (by our parents and elders) that they know cannot really protect us. But they give them to us anyway, because what else is there for them to do? (“Go to school. Study hard”. That kind of thing. “Be good. Be good.”) It is better to go out into the wild, armed with a verse that your elders assure you will keep you from being torn by wild beasts—“It will give you strength to fight”—than to go having nothing, certain that you are going to fail, like it or not.

To “propitiate” (according to the OED) is “[t]o make well-disposed or favourably inclined; to win or regain the favour of; to appease, conciliate.” What the child is to conciliate is that which wants to do him harm. The title of the poem means “knot of bitters” or “dolorous knot”, as Soyinka renders it. But more precisely, “koko oloro” could be translated as “knot that causes pain.” This knot is probably a real plant. Here, it functions doubly as a metaphor.

A metaphor for life.

But how come this “dolorous knot”—this wicked thing—can “plead for me”? What makes the child believe that it can plead? Wherever I may go or be in this world (farm, hill, home, road), please plead for me—you, Knot of Bitters. Life, plead my cause.

But life is pitiless. It can’t plead. Life, not love, is blind. But, also, this life, as Paul Celan said they call it, is still “our only refuge”. The poem refuses a pessimistic, cynical view of life.

Many of us reading this, and the man who wrote the poem, are past that threshold. (The poem is the first in a section in Idanre and Other Poems (1967) called “of birth and death”; the section ends with “Post Mortem”, “let us love all things of grey.”) The shield was taken off a long time ago. What if we now went back to that threshold, the one where we had our first dread of life? What would it tell us? All that dread you carried, all that worry. How far? Did the stream not take your voice? Has the wind not? And the life they said would cause you pain, has it not caused you joy? Have you not loved in spite of poverty? Have you not laughed hard after a hard night of weeping? Has it not been worthwhile—your life?

The tragedy of it all is redeemed by the fact that we have survived what its little voice is burdened by. Cast your voice again. Survive the next threshold.

II

Eleven years after his passing,

I stand at the threshold

of that balcony where he would sit;

the music of his lore, riffling the air

like the lifting of birds;

his voice, in trickles,

undoing the knots of silence.

(This poem, “Thresholds” by ‘Gbenga Adeoba, comes with a note: “In which I visited my grandfather’s house for the first time after his death.”)

The American writer, Lydia Davis, has a story called “Grammar Questions”, about how we talk of the dead, how slippery and inadequate grammar tends to be when we talk about them. “When he is dead”, the narrator says of her father, who is sick and dying, “everything to do with him will be in the past tense. Or rather, the sentence ‘He is dead’ will be in the present tense. . .”

Like Davis, Adeoba, in “Thresholds”, is interested in grammar as it relates to the dead. He is interested in exploiting grammar to circumvent the fact of death. Or rather, he writes to free something of the dead from the conclusive burden that is the past tense, as a way to heal something of grief and momentarily satisfy a longing.

Three of the four “ing” words in the poem (two gerunds, two verbs) are very significant. The first (“passing”) is a noun. It is descriptive of an immutable fact—the grandpa has ceased to exist. But, while Adeoba says “his death” (in his note), it is interesting that in the poem he speaks of “his passing.” The gerund gives a pretence of activity, of movement—as if the old man one morning, eleven years ago, wandered away from his house and is out somewhere in the world, still moving.

Adeoba, standing on two thresholds—the literal physical threshold of his grandfather’s house (of line 2) and the emotional landscape of memory (introduced by the “s” in the title)—scans the balcony where the old man “would sit.” I may be stretching it when I say that, although “would” here is fixed (being the past tense of will), there is also a longing, a desiring, a sense of possibility in that “would.” If the old man could come back from his pilgrimage, if he could turn right at this moment, wherever he may be now in his passing, this balcony “would” be there for him to return to and “sit”.

I have not stretched a thing. Refusing to accept finality, Adeoba holds back the full stop for seven lines. And, to show that he is desirous of the old man’s return, he introduces, after line three, after the past tense—of all punctuation marks—the semicolon.

If the first semicolon—at the edge of line 3 (the second semicolon is properly but not effectively used)—had been a colon, it might be possible to say for a fact that the next four lines are describing a past event. As it stands, we cannot, because the semicolon is a time-, a sense-bending punctuation. It adjusts perception, shifts weight, and puts what comes after and before it in a delicate relationship with each other.

Here, the bigenerous creature (the semicolon) is assent. In using it, Adeoba gives himself license to shade out the lines dividing past from present, so that both are made one. I have suggested that an aspiration is present in “would sit”—the semicolon is his permission to realize, by grammatical means, that aspiration.

The verbs “riffling” and “undoing” are present participles. As has been said, the semicolon was a shift, a slight but seismic shift preparing us for a reclamation of the father from death, a taking-him-from-the-threshold-of-memory, where he lives, and a returning-him- (for the poet) to-the-balcony-to-sit. It is in the two verbs (“riffling,” “undoing”) that the reclamation—the disruption—is done.

Reading the poem’s last four lines, we feel, and are made to feel, that the fact of absence has been suspended, that the activity described is taking place as the poet stands in that moment. We feel that “the air” is the air around the house on the day that Adeoba returns “eleven years after”, not before; that the “knots of silence” being undone are emotional knots.

One thing, though: it is the old man’s voice, and not the old man, that has been freed. Adeoba does not say that the man or (even his stories, “lore”) is what “riffles the air.” Instead, it is “the music of his lore,” and in the next line “his voice,” that acts upon things. In other words, while the old man may be dead, his voice is not. It lives in his grandson’s memory; but also through and in his grandson’s voice. Both voices live now, and will continue to, through the lyric voice of “Thresholds.” The lyric voice being the true metaphor for the human voice, the poem testifies to the triumph of the human voice, over death and time (as several Shakespeare sonnets do). Death cannot touch this voice. It will go on disturbing the air and clarifying difficult silences.

That is the poem’s consolation. And if the fire of our voices will not go out, if it will persevere, endure, and flourish, we have the courage to go on making music. This, poetry, beauty—this is not pointless.

III

“Song”

I can look the sun in the face

But the friends that I have lost

I dare not look at any. Yet I have held

Them all in my arms, shared with them

The same bath and bed, often

Devouring the same dish, drunk as soon

On tea as one wind, at that time

When but to think of an ill, made

By God or man, was to find

The cure prophet and physician

Did not have. Yet to look

At them now I dare not,

Though I can look the sun in the face.

“Neither the sun nor death can be looked at steadily,” wrote La Rochefoucauld in his Maxims (1665). Clark-Bekederemo picked the refrain for this poem from the French writer.

Of his generation of writers, J. P. Clark-Bekederemo was the most notorious. He was considered by many at University College, Ibadan (now University of Ibadan) to be a daredevil, always fomenting trouble. A teacher, M. M. Mahood, said of Wole Soyinka that, on his return from Leeds, he came carrying a basket with a live chicken in it on his head, as a gift for the teacher who had lent him some money when he was broke in Paris. No one could say that of Clark-Bekederemo.

And then came the Civil War, and all the deaths. And all that gusto—that ability to stare down the sun—became useless to him in handling the peculiar challenges of the times. Chief of which was “the friends that I have lost”. But Clark-Bekederemo means something else by “loss”, something different from La Rochefoucauld’s literal “death”. He impregnates the Rochefoucauld with the resonance of W. H. Auden’s death: “We must love one another or die” (“September 1939”). The friends Clark-Bekederemo calls “lost” here had fallen out of love with him—they were dead to him in a spiritual sense. And, in the same sense, he was considered dead to them.

The war made love impossible. Like a kick, it dislocated the intimate circle in which Clark-Bekederemo moved. The poet makes this clear when he speaks of “an ill”, it is bad blood that has infected the fellowship. The force of “I dare not” also makes it obvious that the friends are still there to be looked at. The trouble is that to look at them will break him, because where once the returning look was reassuring, now it would be hostile.

Clark-Bekederemo was a unionist. To somebody like Chinua Achebe and others who stood with the Biafran cause, that was an intolerable position. For his stance, he found himself psychologically naked, bereaved of the people who clothed him, coming close to the verge of total despair. (He writes in thanks to his wife and her parents at the start of Casualties (1970): “for giving me sanity and security.”)

To think about the amount of intensity packed into this short poem, some questions arise: How are we able to handle it? How is it that we can look this little sun in the face?

In an interview with Jim Stahl in 1984, the American poet, A. R. Ammons, put poets in two camps. In one camp, the poets like to manufacture a great amount of turbulence in their lives to make their art intense. (He places Robert Lowell and John Berryman in this camp.) Poets in camp two, on the other hand, already feel a huge amount of turbulence in their own lives. They write poems to manage the whirl they carry on the inside. As he says, “[T]he poet [in camp two] is himself in such an anxious state that he turns to the poem not to create an even more intense verbal environment, but to do just the contrary; to ease that pressure. . . But, he must in the very dissolution or effort to ease that pressure, he must not lose it; the reader must know that it’s there, that that pressure is there”.

Clark-Bekederemo is to be placed in camp two. In “Song”, he eases the pressure of an isolated moment without losing it. The pressure is there. Look at the abruptness of the line-breaks, of the anxiety in “often / Devouring,” “time / When,” “made / By,” “find / The,” “physician / Did.” But then the penultimate line is end-stopped (the only end-stopped line in the poem); we feel a subsiding, and the last line makes peace.

“We have Art”, says the German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, “that we may not perish from Truth”. Clark-Bekederemo kept that in mind. “Song” is a poem in which the heat, though felt, is held under. It is art that keeps us from being smitten by the sun. We can look at it because the poet’s voice does not cave, it is brave in its vulnerability. It consoles in that way. The poem bears its pressure without breaking under it.

Last Notes

In summary, I’d like to sketch some thoughts. Firstly, as I said in the introduction, the poems that console us, like the poems I engaged here, are not always poems that set out to give comfort. They rarely even sound like it. They are not afraid of, and do not dumb down, reality. Think of the “knot of bitters” in “Koko Oloro”, the pressure in “Song”, and the grief in “Thresholds”. Secondly, the consolation of poetry is in the structure of the poem—can it bear suffering and dream? Can it do both at once? The stamina in the structure, its ability to carry terror, ache, and distress without breaking, is what affords us the grace to hoist our own burdens (to paraphrase Ammons). Also, it is a momentary help and is never a substitute for life. As in Adeoba, the full stop may be delayed, but the suspension ends.

Finally, it consoles best because it can stall us. Poetry clarifies and enriches our lives because it can make us stop and look closely at a thing. In reading these poems, in trying to detect their peace, whatever pressures we felt in the self or in the self’s relation with the world before we approached these structures of language that are distillations of spirit, those grinding wheels come to a standstill. And, in a time like this, when the noise is deafening, when the self clamours over the soul, any stillness, however small, is a blessing.

Ernest Jésùyẹmí is the author of A Pocket of Genesis (Variant Lit, 2023). His work has appeared in AGNI, The Sun, Poetry London, The Republic, and Mooncalves: An Anthology of Weird Fiction. He holds a BA in History and International Studies from Lagos State University, Nigeria, and is the poetry editor of EfikoMag.