The success of Sinners can serve as an opportunity to think and take lessons from a decidedly successful film that appeals to its local audience in a very specific way, but also to the global audience, including the Nigerian audience.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

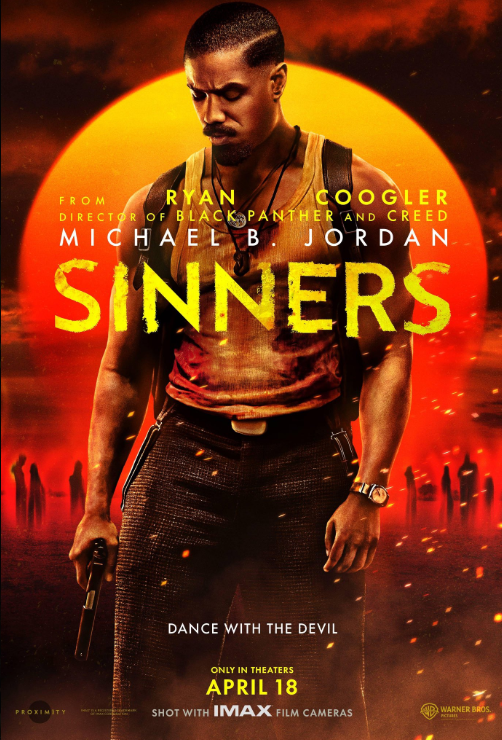

Ryan Coogler’s Sinners (2025) has emerged not only as a major American box office hit but also as an impressive success in the Nigerian cinema space. Of course, Coogler’s ability to sell tickets in Nigeria is no surprise, considering that he gained popularity among Nigerian filmgoers with both Creed (2015) and Marvel’s Black Panther films.

But for a non-IP Hollywood film, it is a huge feat to achieve a 43% increase in sales in its second week at the Nigerian box office while every Nigerian film released on the same date records at least 35% decrease.

Set in 1930s Mississippi in the US, Sinners follows two brothers, identical twins played by Michael B. Jordan, as they return to their hometown in a bid to leave their troubled lives behind only to discover that an even greater evil awaits them there. The film has captivated audiences with its unique blend of genres, compelling storytelling, and universal themes, all while remaining grounded in Black American experiences.

The impressive performance of Sinners offers valuable insights for filmmakers in general. But for Nigeria’s film industry, in particular, which has often struggled to achieve both commercial success and filmmaking excellence simultaneously, events like this serve as a reminder of what is possible and what we hope to one day accomplish.

Now, this is not in any way a Hollywood-Nollywood comparison neither am I positioning Sinners as a blueprint; its scale and resources far surpass what any Nollywood project can access. But the success of Sinners can serve as an opportunity to think and take lessons from a decidedly successful film that appeals to its local audience in a very specific way but also to the global audience, including the Nigerian audience.

In this piece, we explore five lessons that Nollywood can learn from Sinners’ box office success in its valiant efforts to export Nollywood to the world.

Lesson One: Strong Storytelling Still Wins

Let’s start from the basics. Strong storytelling is extremely important. Notice how that didn’t say “strong story” or “strong premise”? Nollywood has a well of good stories. Nigeria is such a diverse country with a chequered history and literally the most incredible plot twists. We could stick to one tiny subset of Nigerian life and still come up with countless good stories.

So over and over again, we go into a film excited about the premise and we come out repeating that overused expression: “Oh, I could see the intention, but the execution was bad”. By execution, we generally mean the storytelling, how the premise is developed into a story and how the film conveys that story, from the writing to the visual and auditory presentation.

It’s a tale as old as time that if you give the same story to different storytellers, you will get different results. That is, after all, how the Bible ended up with four different books about the same man and largely the same events. Even Nollywood has tested this theory, albeit in a characteristically scandalous manner.

Early this year, a Nollywood screenwriter sold the same script to three different filmmakers all of whom initially published the finished work on YouTube. The result was a masterclass in storytelling. None of them was very good, but there was definitely a better and a worse.

In essence, good storytelling is the cornerstone of a good film. It is the reason, or at least one reason, that an outsider with little to no knowledge of African American history can come out of a Sinners screening with the understanding that they have just watched something great.

Plus, a common story can stand out because of how it is told. A vampire story? A group of people all alone and stuck in a building to avoid horrifying creatures outside their door? We have seen these things before, time and time again. The “what” is somewhat easy. The difference is the “how”. How do we get there? How do we say what we want to say?

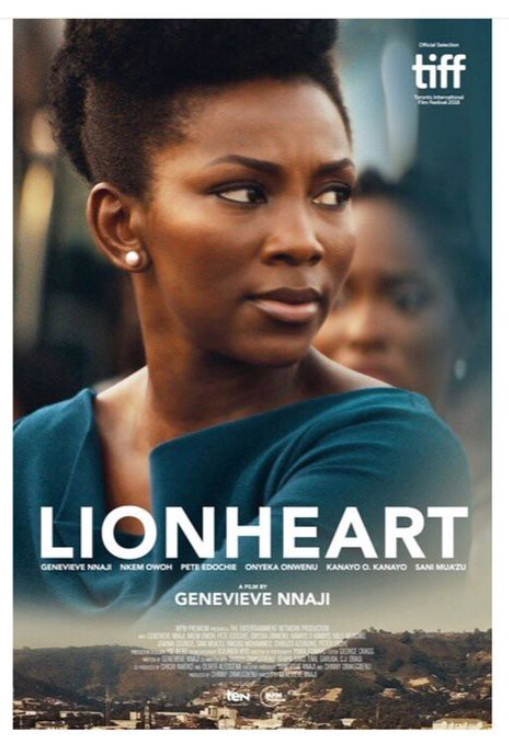

Unfortunately, Nollywood has not figured out good storytelling. There have been outliers, from Genevieve Nnaji’s Lionheart (2018) to C. J. Obasi’s Mami Wata (2023), but too many of our modern films, especially mainstream films, don’t even know what they want to say, let alone how to say it.

Asking for perfection would be unrealistic. Even the best films, including the ones I have cited here, can have a few flaws. But the standard of storytelling in Nollywood needs to go way up. This is not news. Both filmmakers and audiences know that. Nollywood needs to learn how to tell its stories not just with ambition but with intentionality, care, and respect.

Lesson Two: Think Global, but Localise

Between Afrobeats’ global explosion and the coming of the streamers, “Nollywood to the world” has been an important goal for the industry. Thankfully, every now and then, Nigeria’s film industry experiences a global breakthrough, from global streaming records to history-making entries at the “Big Five” international film festivals.

These groundbreaking films tend to have one thing in common. Just as Sinners is deeply rooted in the Black American experience, with universally familiar themes like identity, family, faith, and survival, well-travelled Nigerian films tell stories that resonate universally but are also very culturally specific.

As far back as 2006, Tunde Kelani’s Abeni was the first Nigerian film to screen at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). A Nigerian-Beninese feature, the film tells a transnational “forbidden love” story rooted in the social effects of colonialism. Since then, Nigeria has had multiple films at TIFF with the same winning formula.

Lionheart, which screened at TIFF and became Nigeria’s first film to be acquired by Netflix, is about a woman making her way in a patriarchal corporate world, but the story is steeped in Igbo family and business culture. Unsurprisingly, the New York Times described the film as “globally minded filmmaking that is also comfortingly familiar.”

Arie and Chuko Esiri’s Eyimofe (2020), a very well-travelled film which premiered at the Berlinale and got added to the Criterion Collection, follows two struggling Nigerians living in Lagos and wanting nothing more than to leave their country for better lives elsewhere.

Babatunde Apalowo’s All Colours of the World Are Between Black And White (2023) followed three years later at the Berlinale, with a story about two men who develop an attraction for each other while exploring Lagos amid Nigeria’s anti-LGBT laws and societal norms.

Mami Wata made it to both Sundance and Venice Film Festivals with its fictional West African village at a crossroads between retaining their cultural identity and accepting foreign influence. The film is not set in a real place, but it is even more culturally specific than many modern Nigerian films set in Nigeria.

Editi Effiong’s The Black Book (2023) and Jade Osiberu’s Gangs of Lagos (2023) (which also screened at TIFF) may lean on western tropes, but they both made Netflix and Prime Video history on the back of a specifically Nigerian political context while exploring universally familiar themes of loss, revenge, police brutality and political violence.

The latest is Akinola Davies Jr.’s My Father’s Shadow (2025), premiering as a Nigerian first at Cannes this month, which is set against the backdrop of the 1993 presidential elections as two young brothers spend a day around a troubled Lagos with their estranged father.

With all of these success stories, one would think the lesson would have been learned: that to achieve “Nollywood to the world”, it is not enough for our films to be set in Nigeria with a Nigerian cast. Even establishing an international distribution network, as necessary as that is, will not ensure it. The quality and context of our output are fundamental.

But modern Nollywood is still mass-producing generic and soulless films with vague settings and bleached narratives that are unreflective of the Nigerian reality. If Nigerians are not even buying our stories, why would the rest of the world? We need more films to be uniquely Nigerian, to specifically reflect the Nigerian condition, both past and present, while also being globally relevant in style or in themes, or both.

A prophet is not without honour except in their hometown, so Nigeria’s success stories may not teach Nollywood the right lessons. But maybe a foreign prophet, like Sinners, will.

Lesson Three: Embrace Genre Bending and Diversification

Think pieces have been written about New Nollywood’s restrictive use of genres and the need for genre diversification, and I have authored a number of reviews querying Nollywood’s tendency to work off a list of tropes even in the few genres it is dedicated to. So, there is really no need to overbeat the issue. But I do want to note it as a distinct lesson, while also taking the opportunity to re-emphasise solid storytelling.

Nollywood does not do much of genre-bending or genre exploration, but even when done, it’s hardly well done. From the jarring genre-bending in Sugar Rush (2019) to the floundering takes on western genre concepts like time travel in Day of Destiny (2021) and time loop in Japa! (2024), these films usually evoke excitement and curiosity in audiences, but by the end, we still come out seeing the intention but not the execution.

It’s not just that Sinners defies traditional genre boundaries in combining fantasy horror with period drama, musical, comedy and romance elements; it’s how it blends those elements almost seamlessly and with a clear narrative vision.

You can see how that may be difficult to pull off in an industry that rarely knows what it wants to say or how to say it. Yet, we have also had outliers in this area, too. Films like Daniel Oriahi’s Sylvia (2018) and The Weekend (2024), C. J. Obasi, Abba Makama and Michael Omonua’s Juju Stories (2021), Tosin Igho’s Suspicion (2024) and a few others have done interesting things with genres that Nollywood has often ignored.

Still, Nollywood does need to take more creative risks with film genres to create unique experiences that stand out, at least, in a market saturated with a tiny group of genres. But as we do that, as Nollywood embraces genre diversification, we must hold on to that first lesson: that strong storytelling still wins.

Lesson Four: Invest in Cinematic Quality

I’m not the first to say that the majority of Nigerian films in cinemas have no business being in cinemas. Perhaps a straight line can be drawn from Nollywood’s humble home video beginnings to the grossly uncinematic offerings that we have to pay big bucks for at the theatres. But those were home videos for a reason. Nobody was paying these high ticket prices for them.

Sure, not every film has to be gorgeously cinematic to be worthy of being shown in theatres. But it is such a gift to experience a film so clearly and specifically made for the theatres that you really should not watch it any other way, even if it will eventually make it to streaming.

When you think of films like that, you probably think of the Christopher Nolans and James Camerons of the world, and now Ryan Coogler. And sure, these directors typically have access to a lot of funding, but C. J. Obasi’s Mami Wata is also that kind of film, maybe the only Nigerian film in that class, and it cannot be described as a big-budget film.

Sinners was shot on IMAX film, but we don’t have to go that far. Nollywood can just be more meticulous with the aesthetic language of cinema, from cinematography to sound design, especially sound design. Clear pictures and colourful palettes are not enough. For Nollywood, prioritising technical excellence can significantly elevate the quality of films, making them more competitive both locally and internationally.

Lesson Five: Art and Commerce Are Not Mutually Exclusive

I have referenced quite a number of good, visionary Nigerian films. But one thing about the majority of them, especially the ones that went straight to cinemas, is that they didn’t do very well at the box office. The most cinematic of them all, Mami Wata, made just about ₦4.5Million at the Nigerian box office according to reports, a very discouraging and concerning amount.

So, clearly, learning lessons one to four may earn a film artistic renown, but it may not result in commercial success. And that is important, too. But how do we make art and still make money? I have some ideas straight from the Sinners playbook.

First, strategic marketing, the kind that frames a film’s release as an event, speaks to the audience’s sentiments, evokes a sense of FOMO, and builds on both deliberate and organic word of mouth (sort of like what Rixel Studios is doing with Nora Awolowo and Akay Mason’s upcoming film, Red Circle, but with a narrative hook). It certainly also helps if the film is also a crowd-pleaser.

Of course, strong marketing will cost some money. To borrow words recently spoken by Mo Abudu: “We find that we’re often making movies that don’t have a sufficient marketing budget. And, to be honest with you, it doesn’t really matter how bad this movie is. We’ve seen movies that are terrible out there, international ones by the way, but because they have a decent marketing budget attached to them, you see that people are going out and watching these movies. So, we need to ensure that as we budget the movie for production, we’re also budgeting for the marketing”.

Secondly, strategic casting is a must: a cast full of strong performers—including newcomers, for the culture—but also star power. Think skilled actors who have played major roles in blockbusters, but also think talented new faces and hidden-gem, battle-tested award winners.

Most importantly, collaborations and partnerships cannot be ignored. While Ryan Coogler’s Sundance-winning indie feature debut, Fruitvale Station (2013), did well at the box office, its numbers pale in comparison with the films he has made in collaboration with major studios, whether IP films like Creed and the Black Panther films, or his own original work like Sinners.

In Nigeria, many of our well-travelled films are indie or debut projects or both. And so, after enjoying attention at prestigious film festivals, they come home to an industry manned by gatekeepers, as is the case with every industry, really. It is necessary to form strong partnerships within the industry, especially with influential mainstream producers and distributors who are popular with the audience and have some artistic vision.

It may not be easy, but what part of making a globally well-received film is easy? What matters is that it is not impossible, and it will be worth it.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on Twitter @Nneka_Viv