Across Nigeria, Uganda, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Morocco, these films traced lives lived at the margins of acceptability, where being seen is both a risk and a necessity.

By Joseph Jonathan

Films often operate as acts of refusal. They refuse simplification, refuse comfort, refuse the luxury of distance. At the TSWA Film Festival 2025, several short films leaned into this refusal, insisting that silence—whether imposed by culture, gender norms, illness, tradition, or emotional repression—is never neutral. Across Nigeria, Uganda, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Morocco, these films traced lives lived at the margins of acceptability, where being seen is both a risk and a necessity. What connects them is not form or genre, but a shared urgency: the need to speak, to assert, to break from the scripts inherited by society.

Girl-Boy (Nigeria)

Ajay Abalaka’s Girl-Boy is an intimate and politically charged documentary that centres four masculine-presenting women—Tinuke, Fred, Ella, and Lara—living in a Nigeria that polices gender with brutal efficiency. Rather than flattening their experiences into a single narrative, the film allows each woman her own interiority, revealing how masculinity, womanhood, and queerness intersect differently depending on family, class, and environment.

Tinuke’s journey begins with a seemingly simple question from a stranger—why do you look like a boy?—a moment that becomes catalytic, exposing how early and casually society enforces gender conformity. Fred’s story is steeped in patriarchal negotiation: a gifted footballer forced to abandon the sport she loves to appease a father who equates athleticism with undesirability.

Ella wrestles with inherited masculinity, unsure whether her presentation is self-fashioned or absorbed through proximity to male-dominated spaces. Lara, shaped by childhood labour and survival, confronts the economic cost of nonconformity as employers repeatedly reject her for not looking “like a girl”.

As the women grow older, the stakes escalate. Police detention, public humiliation, familial suspicion, and economic exclusion puncture any illusion of safety. Yet Girl-Boy refuses a narrative of pure victimhood. These women persist. Tinuke finds acceptance at home; Fred chooses distance over suffocation; Lara embraces her masculinity despite social punishment; Ella asserts her beauty on her own terms.

Formally, Abalaka’s choices are deliberate and effective. The stark black-and-white interviews strip the film of distraction, forcing attention onto voice and presence. When colour finally enters, it mirrors the subjects’ growing self-acceptance rather than any societal transformation. The abstract animation—rooted in German Expressionism—eschews realism for emotion, using crooked lines and distorted spaces to visualise a society rigid in its thinking yet hostile to deviation. Girl-Boy is not only timely; it is necessary, carving out representational space where Nigerian cinema has historically looked away.

Say Something (Nigeria)

Chioma Chiatula’s Say Something hinges on a moment many recognise, but few intervene in. Amara (Jackline Assenga), a photographer, witnesses a violent altercation between a couple after a shoot. When she attempts to step in, both parties minimise the danger, insisting everything is fine. The film positions Amara—and by extension the audience—in the uncomfortable space between awareness and action.

While the film struggles with uneven performances that blunt its emotional sharpness, its intent remains clear. Say Something interrogates the social conditioning that normalises domestic violence and discourages external intervention. The couple’s insistence on silence is as troubling as the violence itself, revealing how harm often hides behind politeness, denial, and the desire to avoid “drama.” Though the execution occasionally falters, the film’s moral question lingers: when silence protects abuse, what responsibility do witnesses carry?

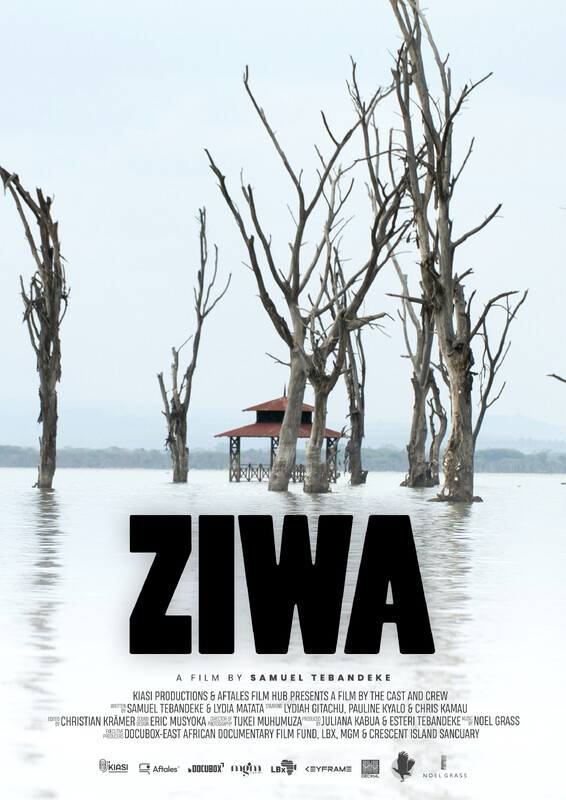

Ziwa (Uganda)

In Ziwa, Ugandan filmmaker turns toward mortality with quiet restraint. Manda (Chris Kamau), terminally ill, is visited by his younger lover, who arrives with both a supposed cure and a desire to revive their relationship. Standing between them is Manda’s estranged wife and Manda’s own refusal.

The film’s emotional weight lies in its resistance to spectacle. Rather than framing illness as a battle to be won at all costs, Ziwa explores acceptance: the choice to stop searching for miracles, to sit with the reality of an ending. The lover’s desperation clashes with Manda and his wife’s resolve, creating a tense emotional triangle shaped by love, regret, and autonomy. In refusing the remedy, the couple asserts control over a body and fate that have already been claimed by illness. Ziwa is a meditation on consent, dignity, and the different ways people grieve impending loss.

Entre Nós e o Silêncio (Between Us and Silence) (Mozambique)

Co-directed by Brenda Akele Jorde and David-Simon Groß, Entre Nós e o Silêncio is a lyrical excavation of mental health, repression, and generational harm. Yara, a young Mozambican woman, exists under the crushing weight of silence, within herself and in her relationship with her mother. The film traces her gradual decision to speak, to name her pain, and to reclaim agency over her emotional life.

The film’s power is inseparable from its context. In Mozambique, as in many African societies, mental health is often spiritualised, dismissed, or rendered invisible. Depression becomes possession; despair becomes weakness. The film confronts these myths without didacticism, using poetry, stillness, and emotional precision to articulate what is so often left unsaid.

By framing healing as an act of speech, Entre Nós e o Silêncio positions vulnerability as resistance. Yara’s journey is not triumphant or tidy, but it is honest. The film opens a necessary space for conversations that Black communities are too often denied, insisting that psychological pain deserves the same legitimacy as physical suffering.

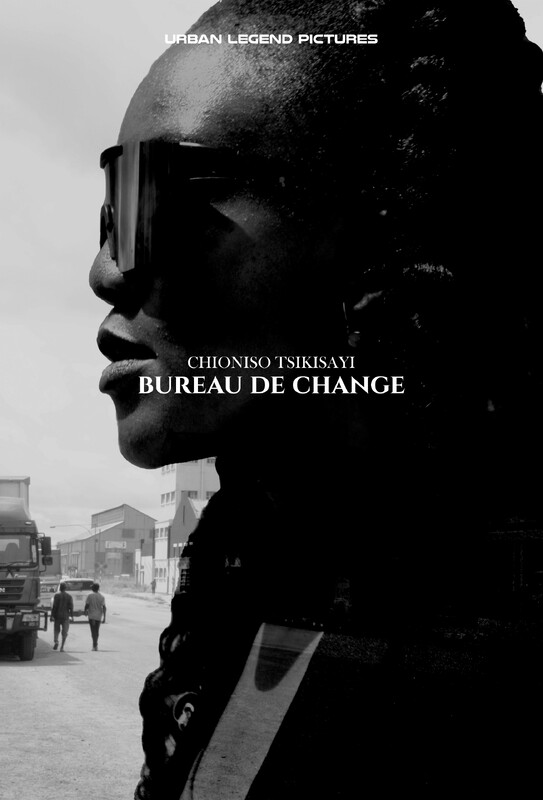

Bureau De Change (Zimbabwe)

Co-directed by Chioniso Tsikisayi and Clinton Zvoushe, Bureau De Change is an experimental, spoken-word-driven meditation on African identity and transformation. Building on Tsikisayi’s earlier short, Queue for a Dream, the film widens its gaze from Zimbabwe to the continent, employing English, French, and Swahili to reflect Africa’s linguistic plurality.

Using the metaphor of a continent seeking a new hairstylist, the film imagines poetry as a site of exchange: a bureau where emotions, histories, and futures are negotiated. The dual meaning of “bureau” as desk and office becomes an elegant conceptual anchor: a place where destinies can be rewritten.

The film resists linear narrative, favouring rhythm, voice, and image. It invites contemplation rather than interpretation, asking viewers to sit with ambiguity. In doing so, Bureau De Change positions African renewal not as a singular project, but as a collective, ongoing negotiation shaped by language, memory, and imagination.

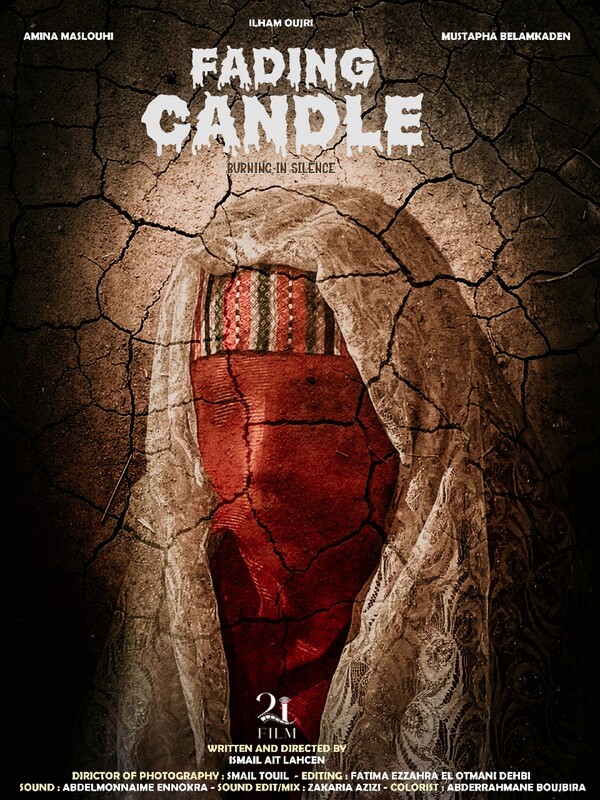

Fading Candle (Morocco)

Ismail Ait Lahcen’s Fading Candle approaches trauma obliquely. A woman touches a wedding scarf, and the gesture unlocks memories of an underage bride, a forced marriage, and an escape marked by silence. The film unfolds through fragments and flashbacks, mirroring the way trauma resists linear recollection.

Rather than sensationalising child marriage, Fading Candle dwells on its afterlife: the caregiver burden, the unspoken grief, the quiet endurance expected of women long after the violence has passed. Lahcen’s restraint is the film’s strength. The candle of the title burns slowly, its light fragile but persistent, illuminating suffering that society prefers to keep dim.

Together, these films reveal a festival programme deeply concerned with visibility: who is allowed to exist fully, who must shrink, and who is expected to remain silent. Whether through documentary, fiction, or experimental form, they insist that personal stories are inseparable from cultural structures. At the TSWA Film Festival 2025, the short film section did not offer easy answers, but it did offer clarity. Silence, these films remind us, is never empty. It is always doing work.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big.