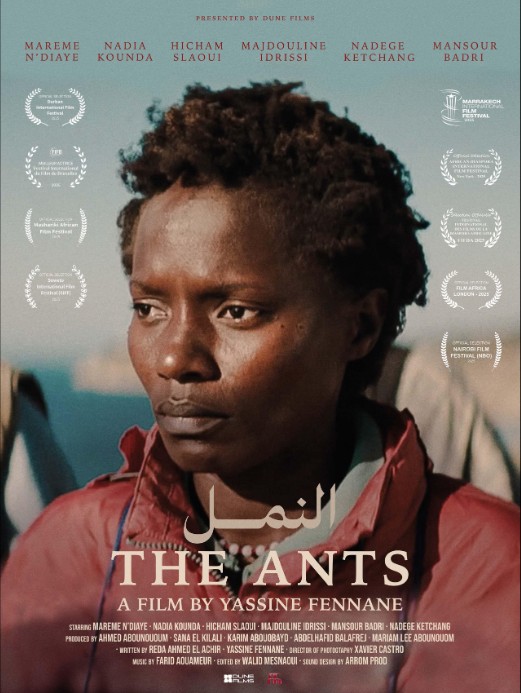

In The Ants, Yassine Fennane interweaves the stories of three vulnerable people across social classes who are trying to rise above their circumstances with their dignity intact.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

“Even the prayers of an ant can reach to heaven” is the first of many proverbs that punctuate Yassine Fennane’s The Ants (Les Fourmis) (2025), appearing on black right before the film cuts to a woman making another woman a promise to bury her with her name and in a Christian cemetery should anything happen to her. Both women have left Cameroon and are about to attempt a perilous ocean crossing on a lifeboat. They round up the conversation with a prayer of Psalm 23—The Lord Is My Shepherd. And in the very next scene, their boat capsizes.

But The Ants is not entirely about the migrating women. In The Ants, Fennane interweaves the stories of three vulnerable people across social classes who are trying to rise above their circumstances with their dignity intact. Set in Tangier, Morocco—considered a transit city, a gateway between Africa and Europe—the lives of the three lead characters intersect while each of them stands at a crossroads in their individual journeys.

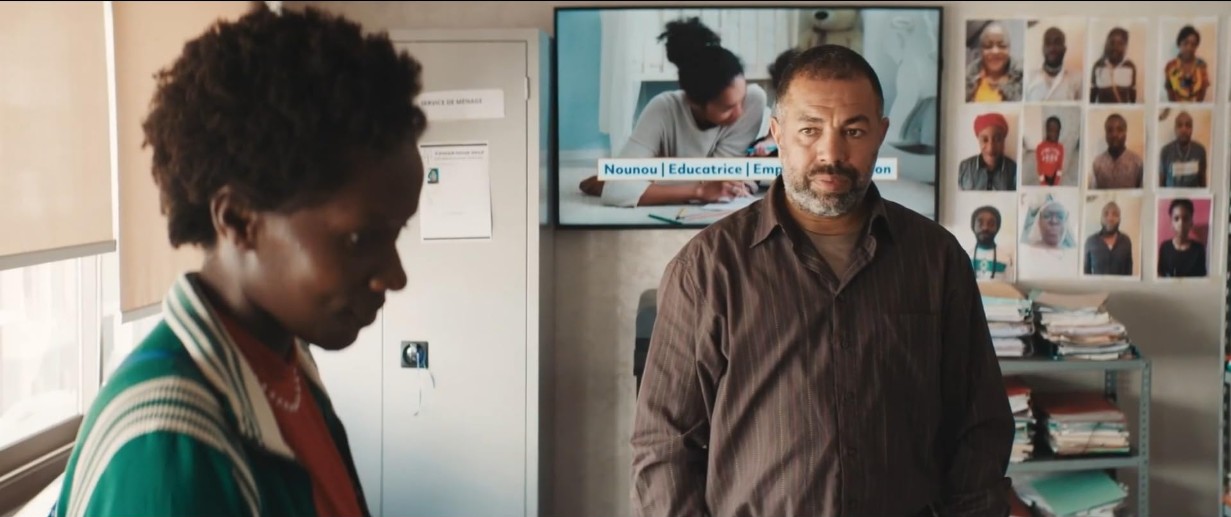

Félicité is a poor, undocumented immigrant who must weigh her morality against survival as she looks for work to feed herself, fund her move to Europe, and give a dignified Christian burial to her friend. Hamid is a recruiter who connects desperate migrants to work in a useful but exploitative system where he himself is both a perpetrator and a victim, but he is also a middle-class family man who is under pressure to improve his family’s living conditions and must confront the repercussions of moral compromise.

And Kenza is a wealthy woman who, though privileged, is battling her own constraints as a wife whose personal needs have been placed on the back burner in service of motherhood and now wants to employ a nanny so she can have some space to seek personal fulfilment.

The Ants is structured in four parts, each of the first three focusing on one character, with the fourth serving as an epilogue. All three characters share one crucial interaction that is replayed from their different perspectives, but their lives collide in a devastating climax triggered by class, racial, and gendered biases. Through their individual narratives and the convergence of their lives, Fennane delicately explores migration, class dynamics, gendered marital expectations, and human interconnectedness, with a nuanced focus on dignity and exploitation.

Simultaneously slow and tense, The Ants unfolds with purpose, propped up by an often dramatic—sometimes haunting—score and a camera that rarely sits still as it follows the story. Fennane consciously frames his characters strictly within their world. Félicité floats with resilience across a sweeping city that is unfamiliar, though not hostile. Hamid moves about authoritatively until his world comes crashing down, and he starts to float, too. And Kenza, whether at home or away from home, is almost entirely restricted within her space, sheltered and nearly suffocating.

Their interconnectedness emphasises that all lives, even across class lines, are intertwined in systems much bigger than themselves. Yet, in all of this, Fennane allows the film to breathe, giving plenty of room to sit with each of the characters as individuals, even when the pace picks up, and the stakes feel more fiercely obvious.

The performances are sturdy. French-Senegalese actor Mareme N’Diaye embodies Félicité with a determined spirit and consistent solemnity. Moroccan actor Hicham Slaoui plays Hamid with a righteous aggression, leaning into ambiguity with just enough suspicion to suggest guilt. And Nadia Kounda, also Moroccan, portrays Kenza with contained defiance. With each of them, silence speaks as loudly as their choices. And through them, their characters insist on dignity, regardless of their circumstances or the role they might have played—at least, in Hamid’s case—in those circumstances.

Fennane’s direction is assured and controlled. But he does overplay his hand with the “ants” metaphor, occasionally resulting in contrivances. However, their message is clear. That the referenced proverbs are pulled from a variety of cultures, from Arab to Japanese and Indian, speaks to the universality of the human condition.

Likewise, their message of divine providence and endurance unto redemption reiterates the film’s philosophy, especially considering the interesting role religion plays in the film as both a marker of faith and morality, and as a psychological support system. Indeed, there is some comfort in believing that even the black ant on a black stone in the dark of the night is under the protection of a divine force.

Still, the ant can be trampled upon, as one of the proverbs declares. But sometimes, it survives. And sometimes, knocking it over is the only way it can see the sky. By the end of this poignant film, there is resignation, there is thriving, and there is simply survival.

Rating: 4/5

* The Ants screened at the African Diaspora International Film Festival (ADIFF) 2025.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time watching, reading about, and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv