What does Oboli’s repeated copyright controversies reveal about the state of copyright protection and infringement in Nollywood?

By Joseph Jonathan

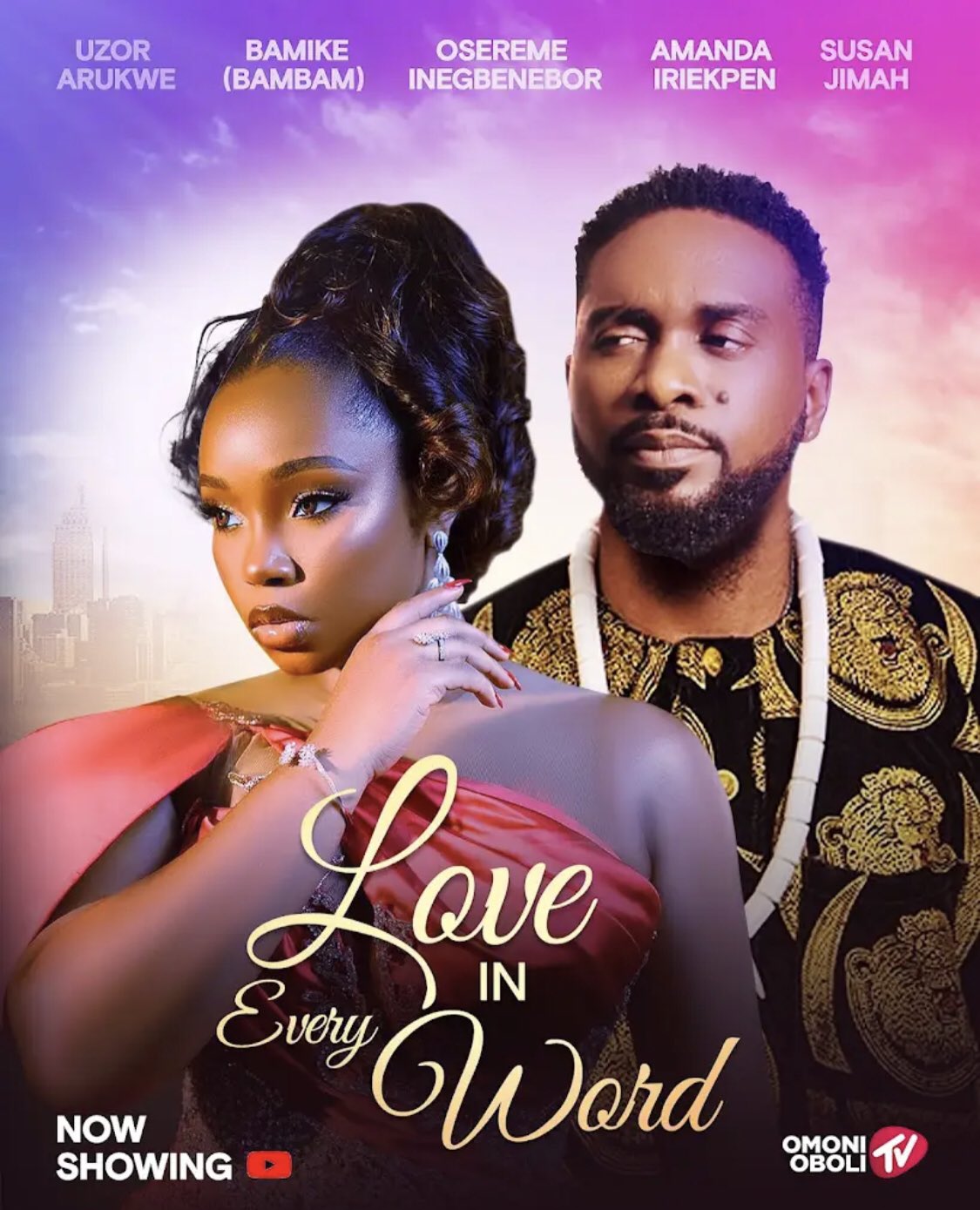

On March 11 2025, Omoni Oboli’s much talked about film, Love in Every Word was briefly taken down from her YouTube channel following a copyright claim, only to be reinstated shortly after. While the details remain unclear, this incident is just the latest in a series of copyright and intellectual property disputes involving the prolific actress and filmmaker.

In 2017, she faced legal battles over her film, Okafor’s Law after writer, Jude Idada, accused her of adapting his script without permission. Earlier this year, she pulled down a film from her YouTube channel after it was discovered that the script bore striking similarities to two other films on the same platform. It was later discovered that screenwriter, Jayne Nwachukwu, had sold one script to multiple producers, raising questions about due process and originality in Nollywood.

It is easy to frame these repeated controversies as an individual problem, after all, why does Omoni Oboli keep finding herself at the center of such claims? However, reducing it to a personal failing ignores the deeper, systemic copyright issues that plagues Nollywood. Consequently, the important question should be: what does Oboli’s repeated copyright controversies reveal about the state of copyright protection and infringement in Nollywood?

To start with, it appears that many stakeholders in the industry do not have a firm grasp as to what constitutes copyright. While this is not intended to be a lecture on copyright law, it is important to emphasise that copyright ownership is considerably complex.

Under Nigerian law, as with many other countries, copyright in a film itself, as an audiovisual work, is vested in the person who makes the arrangements for the making of the film, except where there is a contract vesting copyright in some other person. Typically, the arrangements are made by the producer or the production company.

However, owning the copyright to a film does not translate to ownership of everything in the final product. A film is a collection of various creative elements, including the script, music, pictures, videos, sound design, and more, and some of these elements could be owned by persons unconnected to the film. Such elements should not even make it into the final product without proper clearance as using an unlicensed copyrighted work for commercial benefit generally amounts to a violation of the rights of the owner of the copyright in that work.

One example would be a drone shot taken by a photographer who is not involved in the making of the film, which some observers have speculated might be the reason for the temporary takedown of Love in Every Word.

In February 2024, Nigerian singer, Ewa Cole, filed a lawsuit against filmmaker, Funke Akindele, and music executive, JJC Skillz (Bello Abdulrasheed), for alleged copyright infringement for using her song in the series, She Must Be Obeyed. A more recent example is the case of Chime Chinedu Abumchukwu, who on the 12th of March, 2025 took to X (formerly Twitter) to seek proper credit for his video clips which he claimed were used in Love in Every Word.

Similarly, many filmmakers operate in a gray area when it comes to intellectual property. Unlike Hollywood for instance, where bodies like the Writers Guild of America (WGA) enforce strict contracts, Nigeria’s film industry often relies on informal agreements. Filmmakers and writers frequently collaborate based on verbal promises rather than written contracts that ensure that the terms between the parties are express and clear.

As a result, it is not uncommon to see scriptwriters frequently complain of having their work altered or used without proper credit, while producers themselves argue that ideas are often recycled in an industry built on trends.

For an industry like Nollywood where production schedules are tight and budgets are limited, formal legal protections are often bypassed. This makes it easy for disputes to arise — writers may find their work used without credit, while filmmakers, sometimes unintentionally, find themselves accused of intellectual property theft.

If a lack of proper structure were the only problem, then Nollywood would be in a better place as regards copyright, but as is the problem with the larger Nigerian society, laws are often not properly enforced and copyright laws are no exception.

The primary law which protects copyright in Nigeria is the Copyright Act, 2022 while the Nigerian Copyright Commission (NCC) is responsible for all matters relating to copyright in Nigeria, including administration, regulation and enforcement.

Despite the best intentions of the NCC, the enforcement of copyright laws is slow, expensive, and often ineffective, especially in cases of infringement. Part of the reason being that many disputes never reach court, with aggrieved parties sometimes resorting to social media call-outs. In rare cases where such disputes make it to court, cases could linger for years — as seen with the Okafor’s Law case which took 2 years to complete.

Even when judgments are made, compliance is inconsistent, and penalties are rarely severe enough to deter future violations.

This lack of consequences fosters a culture where copyright infringement is normalised. Producers now assume they can unilaterally tweak a script without an agreement permitting such unilateral alterations. Directors might reuse scenes from another film, betting that legal backlash will be minimal. While Oboli’s visibility makes her an easy target for criticism, the real problem is an industry where getting away with infringement is often easier than proper licensing.

What is all the more interesting and even worrisome about Nollywood’s constant struggle with copyright is the hypocritical nature of most of its filmmakers. Many filmmakers loudly condemn piracy — the unauthorised distribution of their movies — yet the same industry has a weak track record of respecting copyright at the production level.

Earlier this month, Omoni Oboli called out Ghanaian TV stations for airing her films without proper licensing. Other notable filmmakers like Funke Akindele and Toyin Abraham have condemned the frequent piracy of films through unlicensed websites and Telegram channels. But this raises an important question: how seriously does Nollywood take copyright when dealing with its own creatives? If filmmakers want audiences to respect intellectual property, should they not lead by example?

Such hypocrisy speaks to a broader problem in the industry: a selective approach to copyright enforcement. While Nollywood producers and distributors fight against piracy, they often ignore — or, in some cases, actively participate in copyright violations.

Screenwriters, the backbone of any film, are often the ones who bear the brunt of these copyright violations. Many writers in Nollywood complain about being sidelined, underpaid, or outright ignored when their work is adapted without permission.

For instance, in 2019, Nigerian author, Chuma Nwokolo, accused filmmaker Bright Wonder Obasi of plagiarising sections of his short story, Ten Commandments of Nigerian Politics, in Obasi’s 2018 film, If I Am President. Nwokolo’s accusations led to a lawsuit, which he ultimately won, securing proper credit and compensation for his work.

If Nollywood truly wants to protect its creative output, it must first address its own internal contradictions or as the holy bible says, “first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge for many filmmakers is maintaining a balance between copyright integrity and creative pressures. Nollywood’s breakneck production model — where films are shot in weeks, budgets are tight, and audiences demand constant new releases — creates room for ethical shortcuts. Writers are pressured to deliver scripts quickly, sometimes leading to accidental plagiarism. Producers, racing against deadlines, may skip proper rights clearance. Directors, under pressure to stay relevant, might borrow concepts without thorough checks.

Omoni Oboli herself exemplifies this need to stay constantly active. Being one of the drivers of the “Nollytube” movement, she has built a reputation for prolific output. In fact, Love in Every Word was barely two days old when a section of her fans began clamouring for a sequel. But could this drive to always have a new project in the pipeline be a factor in her repeated copyright controversies? When a filmmaker is juggling multiple projects at once, it becomes easier to overlook or deliberately bypass important legal steps.

Oboli’s repeated involvement with copyright disputes are not just about her, they are a reflection of an industry that has yet to take copyright protection seriously. While it is tempting to single her out as an exception, the reality is that Nollywood’s copyright problem is widespread.

She might be the perfect scapegoat due to her popularity and as such, attract much scrutiny but her case merely highlights systemic issues within Nollywood, exposing the flaws in an industry where many are guilty, yet few are held accountable, just as the Nigerian Pidgin saying goes: “na who dem catch be thief”.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @JosieJp3.