More importantly, the stigma associated with dreadlocks shows favoritism and protection of colonialist culture and punishment of African culture.

By Olumuyiwa Aderemi

Recently, the Governor of Niger State, Nigeria, Umar Bago, issued an executive order to law enforcement agencies within the state to arrest citizens wearing dreadlocks, going so far as empowering them to shave their hair off and impose a fine on that person. For the uninitiated, his actions amount to abuse of state power. In his defence, as an elected official and constituted authority, he claimed to have acted in what he believed was the best interest of ensuring the security and stability of his state.

Though the order has since been rescinded, the governor’s actions have implicitly linked dreadlocks to rascality, thuggery, and crime. This could embolden some law enforcement officers outside the state—already notorious for carrying out illegal stop-and-search operations and arrests of young Nigerians—to find legal justification for profiling and prosecuting individuals simply for wearing dreadlocks, since a sitting governor has deemed such a hairstyle to be the mark of a criminal.

In addition, other states may decide to follow suit. In a country that is allegedly democratic, the Nigerian society constantly metes out oppression and citizen subjugation, reinforcing the idea that the rights of citizens are miniscule, if not non-existent, and that what the government gives, it can also take without recourse to whether such is legal or otherwise.

This is about more than hair. It’s about identity and culture. For as long as I, or anyone else, can remember, dreadlocks have always been a site for cultural conflict, criminalised not because of crime but because of what they represent. The question is why?

Deadlocks have been said to be synonymous to non-conformity. Some history books would have more than a million and one reasons as to what made it so, but one thing that they all have in common is that they opine that dreadlocks originated with the people of Ethiopia during the reign of Ras Tafari (also known as Halie Selassiie), the country’s last emperor during the period of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War.

When Italy gained the upper hand, Ras Tafari fled into exile to garner international support to free Ethiopia from Italian invaders. In gaining international support, the Jamaicans resonated with Tafari’s bold move to challenge Western influence, which caused them to regard him as the Second Coming of Jesus, here to free Africa from Western invaders.

In solidarity, Jamaicans began wearing dreadlocks and referred to themselves as “Rastafarians”. With time, this ideology spread, and the notions of resilience, independence, and defiance of colonial rule became recognised as the raison d’être of dreadlocks, both within and outside Africa. More than this, some African tribes believe dreadlocks to be a symbol of spirituality.

The Yoruba traditional religion holds that when a child is born with dreadlocks (known in their native language as ‘dada’), the child possesses spiritual power and is to be highly revered. An example of this is the common belief among members of the tribe that only the mother of such a child is permitted to cut the child’s hair upon reaching puberty.

The hair, once cut, is preserved in a jar with water and mixed with herbs, the combination of which is believed to have healing properties should the child get sick. Even though the reason for cutting the hair is to help the child align with societal norms, such a child is still regarded as having been touched by extra-terrestrial powers.

History books also suggest that dreadlocks are found in Hindu culture, where they are called ‘jaṭā,’ symbolising their followers’ devotion to the Hindu god Shiva. All of this points to the fact that dreadlocks have always represented spirituality, community, rejection of colonial expectations regarding grooming and appearance, and a tool for freedom from Western influence—values that existed outside Nigeria but also during the country’s colonial period.

It is deeply ingrained in Nigerian history that the colonial era was characterised by oppression, and the colonial government did more than simply profit from the country; they actively sought to erase any semblance of Nigerian heterogeneity and sense of self. One such way was through the Christian missionaries, who labelled African hairstyles, such as dreadlocks, as savage or improper according to their religious beliefs.

This formed one of many structures which, unknowingly, have been ingrained into contemporary Nigerian society. Most colonial structures were never dealt away with but rather retrofitted and maintained with little foresight on whether these structures fit Nigerian peculiarities.

Some may argue, for example, that recent amendments to extant laws or the enactment of new laws to meet the dynamism of the Nigerian society defeats this fact. However, the societal disdain for this core component of Nigerian, and also African, heritage, makes for a strong counter argument, as exemplified by the actions of the Niger State governor.

This shows that being independent, as a country, is more than just words and actions; it’s about the mindset. The failure to question why dreadlocks are criminalised, their origins, their meaning, and, most importantly, their significance, has led most Nigerians, especially the millennials, to internalise the colonial mindset decades after Nigeria’s declaration of independence and integrate the same into our way of life. These continue to linger in the media, religious spaces, and homes.

For example, in a typical family setting in Nigeria, most parents groom their male children to shave off their hair when it gets too thick as a show of good home training and responsibility. In educational institutions, particularly ones established by the early missionaries, such as King’s College, Lagos, and St. Gregory’s, the hair is expected to be completely shaved off. Within the religious space, having too much hair on your head, as a male, is a sign of recalcitrant behaviour. Lord help you if either of your parents holds a significant position in the church.

Specifically, the stigma associated with dreadlocks is often felt by young people, particularly those from Generation Z. Individuals within this demographic who wear dreadlocks are frequently profiled as dubious, fraudulent, lazy, or even as cultists. This stigma is also not gender-neutral. Men with dreadlocks are harassed, arrested, or profiled as criminals. Such perceptions, among other factors, have enabled law enforcement agents, under the guise of exercising their powers to arrest, investigate, and maintain law and order, to arbitrarily violate the rights and personal dignity of young men. This was the modus operandi of the now-defunct SARS unit.

Women with dreadlocks are not exempt from this stigma. They are often subjected to moral judgement, especially in the workplace, where dreadlocks may be interpreted as signs of rebellion or unprofessionalism. This was evident in 2018 when a woman from Alabama, Chastity Jones, was denied a job because of her dreadlocks. In Nigeria, respectability politics are deeply ingrained, and a woman wearing dreadlocks is seen as running counter to the image of the ideal Nigerian woman, one who is expected to be modest, submissive, and culturally refined. Additionally, Nigerian women are often expected to conform to narrowly defined roles: mother, wife, or spiritual devotee. Wearing dreadlocks challenges these ideals and is, therefore, frowned upon.

A woman with dreadlocks may also be subject to hypersexualisation or seen as excessively liberal or radical, especially within Nigeria’s conservative cultural landscape, where hairstyles are closely tied to perceived virtue. In Nigeria, a woman’s hair is expected to be relaxed, braided, and tidy to align with religious and cultural expectations, whether she is Christian or Muslim. In corporate Nigeria, within fields such as law or banking, patriarchy enforces unspoken dress codes, rewarding conformity while penalising natural or dreadlocked hair.

Although discussions around the stigma of dreadlocks often centre on men, women also face similar prejudices. These experiences reveal a gendered double-bind: men with dreadlocks are criminalised, while women are moralised against. Class and celebrity status further influence these gendered experiences. The decisive factor here is money. For example, when a male artiste like Burna Boy or a female artiste like Asa wears dreadlocks, it is seen as fashionable and even admired, sometimes by the very law enforcement officers who would otherwise condemn it. In contrast, non-celebrities with dreadlocks are often perceived as threats to society, presumed more likely to rob a neighbour or steal a car.

In a heterogeneous society like Nigeria, unity of purpose is the only way forward. Divisions only work against this, and creating a class dynamic between those who wear dreadlocks and those who don’t may seem trivial. However, in the bigger context, little drops of water make the mighty ocean, as seen with movements like #EndHunger, #EndSARS, and #EndBadGovernance.

Analysing the legal perspective and how dreadlock stigma is contradictory to extant Nigerian laws are the wordings of Section 1(1) and the fundamental human rights provisions of Section 34(1)(a) and Section 42 of Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution.

Section 1(1) provides that “this Constitution is supreme and its provisions have binding force on all authorities and persons throughout the Federal Republic of Nigeria”. Section 34(1)(a) of the Constitution provides that “Every individual is entitled to respect for the dignity of his person and accordingly, no person shall be subject to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment”. Lastly, Section 42 states that any Nigerian citizen is free from discrimination. As provided for in Section 1(3) of the Constitution, “If any other law is inconsistent with the provisions of this Constitution, this Constitution shall prevail, and that other law shall to the extent of the inconsistency be void”.

Being the primary law which gives all other laws in Nigeria their validity, the provisions of the Constitution supersede other laws in Nigeria and any that runs contrary to the Constitution is to the extent of its inconsistency, null and void. For any executive order made by a sitting governor to have the effect of law, such must have been ratified by the state’s house of assembly and published in the state’s gazette.

Once this occurs, the order becomes law, enforceable throughout the state. However, it only amounts to subordinate legislation and must not contradict the provisions of the Constitution. This principle was established in the case of INEC v NNPP (2023) 12 NWLR (pp. 460, paras B-D), where the Supreme Court of Nigeria held that any conflict between substantive and subordinate legislation must be resolved in favour of the substantive legislation. As the Court stated, the substantive legislation “is the pillar against which regulations (subordinate legislation) made thereunder lean, and so the regulations can never supersede or override” the substantive legislation.

This discrimination and stigma associated with dreadlocks is also frowned up by international treaties and conventions, of which hold the force of law in Nigeria. Article 2 of the African Charter On Human And Peoples’ Rights, which has been ratified, domesticated, and is enforceable in Nigeria, provides that “Every individual shall be entitled to the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms recognized and guaranteed in the present Charter without distinction of any kind such as race, ethnic group, colour, sex, language, religion, political or any other opinion…”

An analysis of these legal and judicial precedents proves that discrimination, in all forms, is against Nigeria’s constitutional protections of the dignity and culture of its citizens, which includes the right to wear dreadlocks. However, the actions of the Niger State governor, though short-lived, abuse this protection and undermine the rights of citizens in the state and, by implication, Nigerians in general.

To reshape this narrative, it is important to understand, once again, that this is about identity and belonging, not just hair. Dreadlocks have always been a source of pride in Africa and an element of counterculture against the intentions of colonialists. Dreadlocks represent a bold declaration of independence and strength in African patrimony.

This is the philosophy championed by Nigerian Gen Z, resisting efforts at being imprisoned by certain components of Nigeria’s traditional and linear culture. Music and pop-culture influencers like Flavour are positioning dreadlocks as a style and statement in today’s youth culture. While they are exempt from the stigma associated with the hairstyle due to their celebrity status, they serve as forerunners in reclaiming dreadlocks as a symbol of African fashion and contemporary style, a sentiment that resonates within Nigeria as well.

Impliedly, their wearing of dreadlocks is a call for a more inclusive and culturally-aware government in Nigeria, which can be done with sensitisation programmes on the breach of fundamental human rights of citizens, which are caused by the discrimination and illegal profiling that comes with wearing dreadlocks.

More importantly, the stigma associated with dreadlocks shows favoritism and protection of colonialist culture and punishment of African culture. Years after gaining independence from foreign powers with the freedom to make decisions for ourselves and establish a society that protects and celebrates the distinctness of Nigeria and we’re using it to idolise external influence to our prejudice. This erodes a part of our Nigerian ancestry and, by implication, African uniqueness.

Olumuyiwa Aderemi is a culture writer exploring the nuances of culture and its influences – both from the past and those still shaping us today. Through his work, he hopes to uncover overlooked aspects of culture that he missed while growing up and inspire others to do the same, ultimately becoming agents of change. Connect with him on Instagram (@gocrazymag) and X (@muyiwavstheopp).

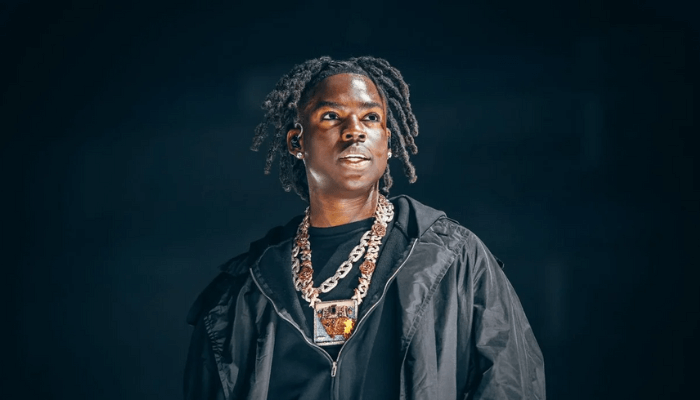

Cover photo credit: Adobe Photos