Perhaps there are other historical novels set in Lagos, but few are as captivating, imaginative and yet historically detailed as The Parlour Wife.

By Evidence Egwuono Adjarho

The first time Kehínde decides to take her brother Taiye’s advice, something bad happens—and she cannot forgive herself for it. Not only does she make her father angry (an unfamiliar experience for Kehínde, who is a classic daddy’s girl accustomed to his constant praise), but that angry look on his face becomes the last memory she has of him.

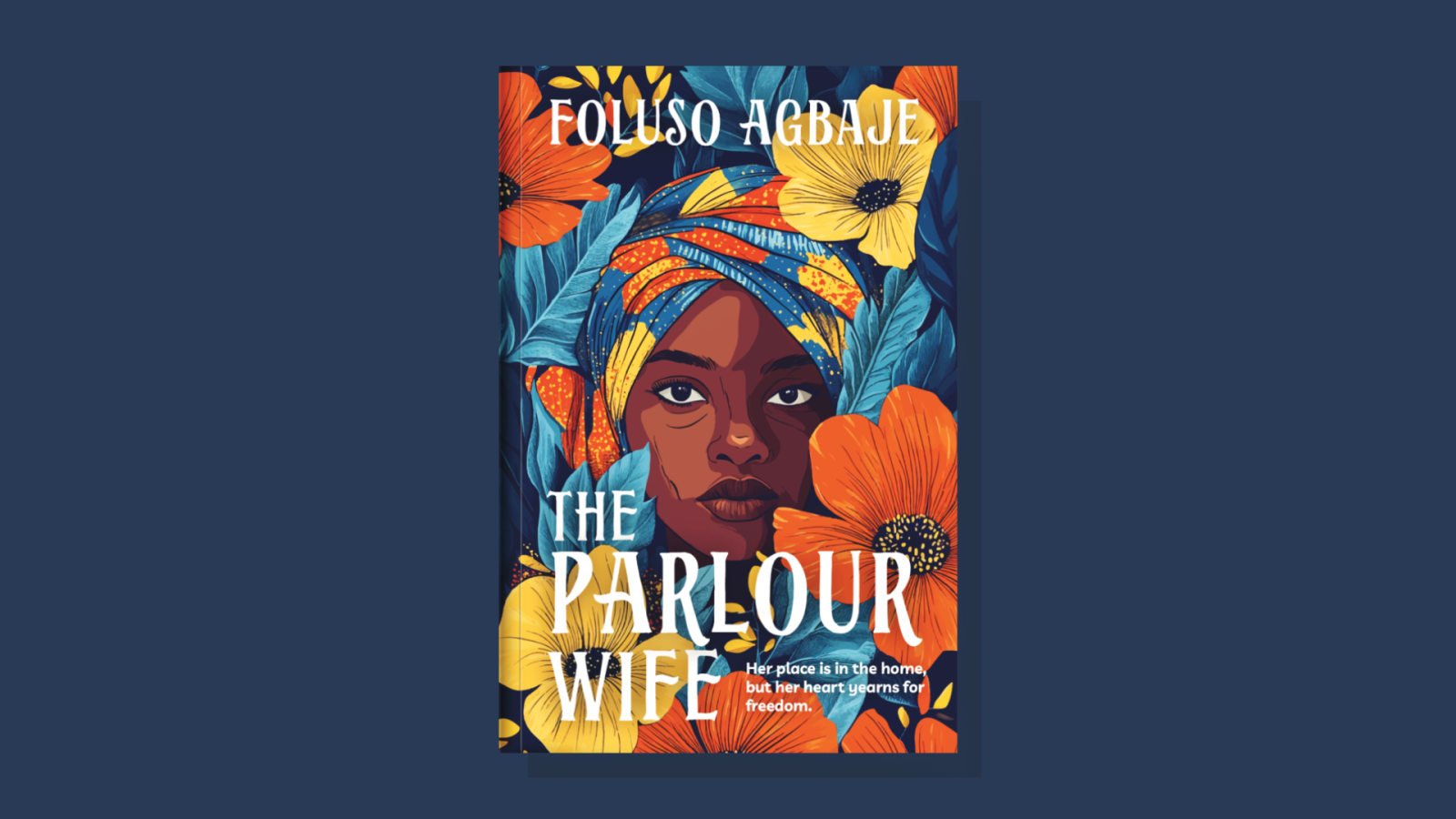

The Parlour Wife by Foluso Agbaje is set in colonial-era Lagos and is easily identified as the compelling story of Kehínde, a young woman navigating both her internal turbulence of fear, self-doubt, and denial, and the external turmoil of a city grappling with the effects of the Second World War.

The novel is structured in three parts, each representing a distinct timeline. But the shifts between these parts are not merely chronological. What distinguishes them is how Kehínde and everyone and everything connected to her undergo significant transformation.

In the first part, Kehínde is mostly revealed to us through her thoughts. She is described as “Pretty, quiet, always smiling, so agreeable”. And rightly so. She struggles to express her true feelings, desires, and disdains, and is constantly silenced by the fear of her parents’ disapproval.

Her twin brother, Taiwo, is presented as her alter ego. Unlike her, he is outspoken, assertive, and unafraid to challenge their parents’ authority. It is he who informs their father of their career ambitions which contrasted with the plans their parents had mapped out.

He hopes to enlist in the army while Kehínde, having received an offer from the West African Pilot, dreams of being a political writer. Kehínde, too timid to speak for herself, lets Taiwo do the talking. Throughout this section, we see her repeatedly wishing she was more like him.

The Parlour Wife’s rising action arguably begins when Kehínde is married off to Mr. Ogunjobi. Though she had been warned of this arrangement before her father’s death, she once again finds herself unable to protest. Foluso Agbaje draws a parallel between Kehínde and her country: “Kehínde was like Nigeria, silently screaming about her rights to parents who thought they knew better”. But the problem with silent rebellion is that silence is often mistaken for consent, or reshaped into it.

The latter is precisely Kehínde’s fate. Though unwilling to be the third wife of a man old enough to be her father, she convinces herself otherwise during a heated argument with Taiwo: “I’m doing what’s best for our family!” But Taiwo exposes the hollowness of this justification: “You care so much about what everyone else thinks that you can’t even go after what you want!”

This moment is highly symbolic in The Parlour Wife. It marks the climax of Kehínde’s internal conflict: her growing awareness that her actions are not only harmful to herself, but also shaped by expectations she no longer believes in, yet still lacks the courage to reject.

In the second part of the novel, Kehínde begins to mature. She becomes less intimidated by her domineering husband and his sharp-tongued first wife. She also begins making independent decisions. This Bildungsroman structure lends itself well to both character development and narrative progression. Kehínde transforms from a passive thinker into a woman of action. She becomes secretary of the Lagos Market Women Association (LMWA), a role that is in line with her earlier dream of political writing. Though she is unable to take the job at the West African Pilot, she ends up performing similar work under the leadership of Madam Titi.

Kehínde’s growth is also marked by her departure from societal expectations and moral codes. Unlike the quiet and reserved girl introduced in the opening pages of The Parlour Wife, the later version of Kehinde allows herself to fall in love with Emeka, the brother of her shop neighbour, Ama.

This ‘forbidden’ relationship becomes the novel’s central conflict. Kehínde knows her actions risk scandal and punishment—why should a married woman take a lover?—but “She ignored the roaring sound in her head… she refused to think, each thought of her parents, Taiwo, the LMWA, Baba Tope, Ayo, what anyone would think, what the consequences would be.”

As Lagos edges toward the devastation of war, the atmosphere of unrest intensifies. Market prices rise, demand outweighs supply, and uncertainty looms. Even the once-wealthy, like Baba Tope and his friends, are reduced to struggling. The LMWA, under Madam Titi’s leadership, plays a crucial role in resisting colonial oppression. They are able to stir the market women to stage a peaceful protest against the colonial system. Although uncertain of the outcome, they are nonetheless unafraid to confront the systemic corruption of the Lagos government. This political awakening marks Kehinde’s full transformation in The Parlour Wife.

Meanwhile, Kehínde’s family begins to unravel. Like Kehínde, her mother and brother also undergo significant changes. Following the death of her husband, Kehínde’s mother quickly moves from authoritative to withdrawn and uninvolved. Not even the conflict of her twin children, Taiwo and Kehínde, can break her resolve.

Similarly, Taiwo fades into the background a few chapters into the novel. This was somewhat disappointing because of the initial portrayal of this character as important. But again, we are reminded that the author is a god— able to make alive and unalive at will.

Stylistically, The Parlour Wife demonstrates an impressive command of language. However, the book’s frequent use of similes occasionally slows the pacing for readers. While vivid description is one of the book’s strengths, an overreliance on comparison did feel repetitive and redundant.

Still, this novel deserves praise for the depth of historical research it clearly reflects. Perhaps there are other historical novels set in Lagos, but few are as captivating, imaginative, and yet historically detailed as The Parlour Wife. Even fewer foreground the role of women in Nigeria’s protest against colonialism. For this reason alone, The Parlour Wife stands out and is wholeheartedly recommended.

Evidence Egwuono Adjarho is passionate about African literature and is committed to amplifying its reach through book reviews and engaging video content. She is currently training as a photographer. Connect with her on Instagram, X, Facebook, and LinkedIn: @evidence egwuono.