Not many recent novels from Nigeria would trump Years of Shame’s innate ethical ambition. It has the seeds of a story that can endure for the ages—history, multi-generational saga, and moral concupiscence.

By Chimezie Chika

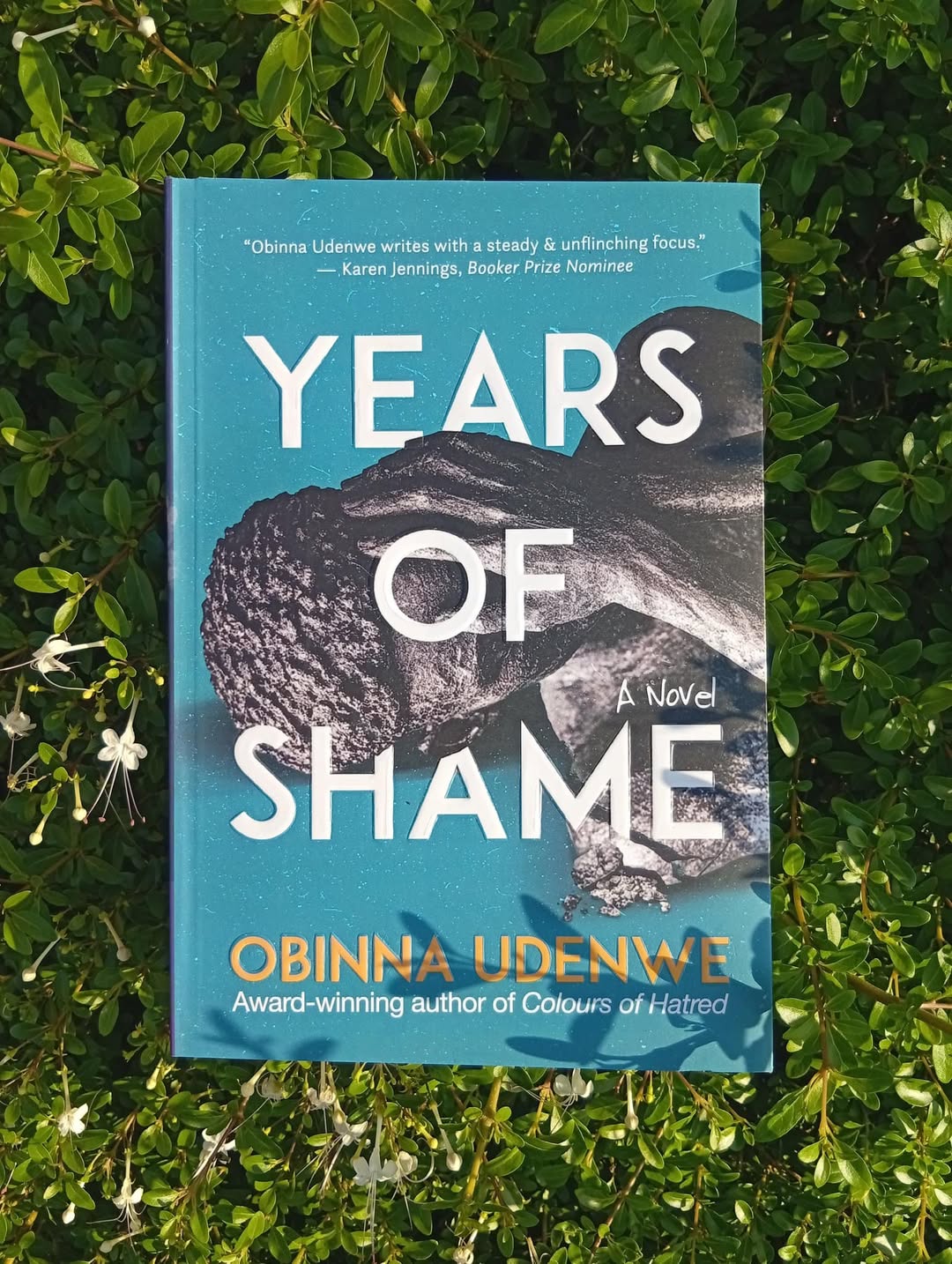

What happens when a man’s worst nightmares become reality? How does he face the world and where does he go from there? These are the questions that propel the beginning of the thoroughgoing tragedy that helms Obinna Udenwe’s new novel, Years of Shame, which is his third novel, coming after his 2014 thrilleresque debut, Satans and Shaitans (2014), and the award-winning Colours of Hatred (2019).

When we first meet Patrice Ikebe, the hubristic anti-hero of Years of Shame, in the early pages, he is running away from his village in an early morning fog, having taken a grievous traditional oath whose extensive repercussions—on himself and his lineage—he has even yet to comprehend at that point.

Subsequently, he would spend the rest of his life in flight from himself and his one heedless error. What we initially glean in Patrice and the corollary of events that spiral out of control from that fateful oath-taking—which had happened because he accused a kinsman of stealing his money—is the significance of the meanings of masculinity and emasculation in our culture.

To this end, Years of Shame asks a troubling moral question: who is a man when he is nothing, and what is he willing to do or not do? The exploration of masculinity here is layered on levels that affect marriage, business, culture, family, history, and patrimony. And Patrice Ikebe, the vehicle that ferries these questions, is caught haplessly amidst forces—metaphysical or otherwise—beyond his puny human control.

The plot of Years of Shame can best be described as a Nigerian reinterpretation of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex—an ancient story whose central Oedipal calamity is almost deviously exploited here by the author. On that note, Udenwe’s novel is, in a circuitous way, an old-fashioned tragedy, wherein all the tragic steps and archetypes are staged and fully played out. As old-fashioned tragedies go, it has that profound aura of the inevitable, of fate marrying with destiny.

This somewhat complicates some of the plot points with the kind of aberrant implausibility characteristic of such tragedies, in a sense (of which some of those faults should be borne by the author).

For example, why would Patrice, a man who supposedly owns vast rice paddies, refuse to farm them upon his terrible descent into penury but instead choose to go work as a laborer for his former master for peanuts? There are many other issues like this, which are not so much a problem as there being no explanation offered.

Nevertheless, Years of Shame, is a wise book, unlike anything Udenwe has written previously (which is why its disappointments were pretty hefty when they began to rear their hydra-headed monstrosities—but we will come to that). I would go as far as to say that this book is highly inspired; its language is delightfully peppered with many proverbs and idioms that delineate the rhythms of Igbo speech. The structural foundations of the novel’s language recuperate the Achebean storytelling tradition, in which traditional life and philosophy are conflated lyrically with modernity.

The traditions that Udenwe recuperates—those of the people of present-day Ebonyi state in Nigeria, which have not featured much in our literature, with the exception of the Igbo classic, Omenuko—are riveting in the historical sense, telling the flip-side of an important story which had bracketed the sidelines of Nigerian history, the Ogu Teteri or the First Izii Revolt of 1969-1970, in which the people of Abakaliki and environs rose against the tyranny of murderous Aro settlers in their midst who were systematically decimating them. As Udenwe explained in his Author’s Note, all these played out under the cover of the larger Biafran War.

Thus, on the peripheries of Nigeria’s larger tribalism, there existed intra-tribal prejudices of which the one directed towards the people of Abakaliki and Ebonyi environs is prominent. In general, Years of Shame does a good job of placing the city of Abakaliki on the literary map.

Udenwe’s Abakaliki throbs here with life, colour, and music. And again: Has there really been any vivid portrayal of that historically dissimulated city in Nigerian fiction? Barring Udenwe’s previous fiction, I think not.

In Years of Shame, we see the Izii-Aro conflict fleshed out in the relationship between Patrice Ikebe and his master, Chief (Sir) Douglas Akidi, wherein the latter treats the former and all his Ebonyi kin as less than second-class citizens, subalterns of his fiefdom, culminating in the pivotal rape that finally led to the story’s Oedipal outcome.

Udenwe’s characters are remarkably alive, memorable, and the novel’s set-pieces, or the attempts thereof, are heightened by the poetic yet realistic dialogue. From the outset, Years of Shame occupies the terrain of mythical conceit—the sort of technique that a novelist such as Chigozie Obioma has brought to the fore in recent years (and mythical madness features here as well).

But more than this, Udenwe is even more thoroughly naturalistic in how he positions his characters against the idea of fate and moral consequence. This propensity towards naturalistic determinism is clearly where Udenwe excels, except where his somewhat unnecessary use of suspense early on breaks that spell.

How piteous it is indeed that the delightful strange mythic force, an inexorable sense of foreboding, that propels this story is often broken by so many technical issues which, even when routinely ignored at first, become increasingly frequent and egregious. One of the first things I noticed was characters calling the Nigeria-Biafra War “Civil War”, which when translated into Igbo, raises personal doubts that any local in Igboland in 1976 referred to the war in that way.

The novel’s early sequences were as spell-binding as any promising a glimpse of literary greatness, but that early gravitas soon tapered off, only subsequently undulating between gratifying highs and pedestrian lows (sentences can sometimes be as bad as those found in the middle of page 201).

Such lows reach their apogee with Udenwe’s descriptive insistence on telling us how fat Ekwutosi, Chief Douglas Akidi’s first wife, is. This book has seven sections and there’s hardly any without yet another obscene description of Ekwutosi’s bigness. Here’s one between pages 204 and 205:

There was no need talking about her stomach, for when she sat, her stomach protruded down in folds, almost extending to the floor. Now, she mostly did not go out, for to walk was a Herculean task. Her face was puffy, with assorted flesh covering her cheeks and jaw area, ensconcing her ears, making them appear small.

Does this even contribute to the narrative? Even if it does, the repetition of that singular description makes a mess of whatever the writer’s intention was supposed to be. In addition, while I need not say much regarding the quibbling punctuation errors, newer editions of this book would immensely benefit from detailed copy-editing.

The most embarrassing of this book’s problems has to be the major typesetting error between pages 236 and 253. The sixteen pages in-between are missing; instead what I got in my copy was a regurgitation of pages 189-204. Not the best advertisement for Udenwe’s fledgling publisher, I must say.

In short, an author of Udenwe’s stature should by now be above these petty publishing and editorial fumblings, or is this yet another frustrating instance of the “Nigeria factor” rearing its now familiar chameleonic head?

The big lesson here is that the enterprise of writing and publishing is a patient affair and should not, under any circumstances, be rushed, as if there is any lifetime award for great haste in literature (which there isn’t literally—ask the Nobel and others, if in doubt.)

Nonetheless, not many recent novels from Nigeria would trump Years of Shame’s innate ethical ambition. It has the seeds of a story that can endure for the ages—history, multi-generational saga, and moral concupiscence.

Udenwe is not your ideal stylist, or anything of the sort, but on the basis of the idea of a story as something that stimulates memory and imagination, what he has offered us in Years of Shame is a tale that has a heart, his best yet. It is only a shame that editorial neglect has marred its thesis for greatness in this year, or perhaps, other years.

Chimezie Chika is a staff writer at Afrocritik. His short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Weganda Review, The Republic, Terrain.org, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Fahmidan Journal, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, and Channel Magazine. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture, history, to art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on X @chimeziechika1