It is perhaps this deep grounding in Yoruba history and mythology that earned Sanya a spot on the shortlist for the Nigeria Prize for Literature 2025. And deservedly so.

By Evidence Egwuono

Literature, among many other things, serves as a mirror to society. Perhaps no writer embodies this idea more profoundly than the venerated William Shakespeare. Through his tragedies, Shakespeare revealed the dangers of unchecked power, unbridled ambition, and the inevitable consequences of human choices—whether seemingly good or bad.

At its core, his work reflects the nuances and complexities of human nature. For instance, Macbeth’s extraordinary battle skills eventually gave way to an insatiable thirst for power, fostering a dangerous sense of invincibility that ultimately led to his downfall.

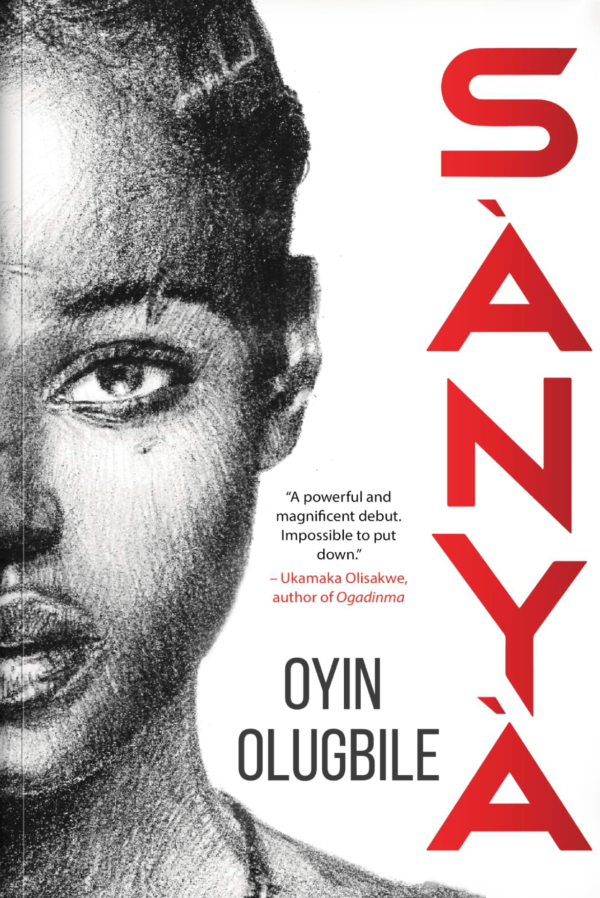

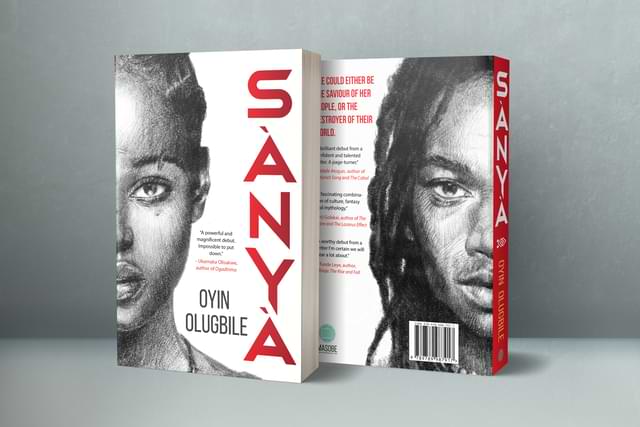

As a research student, it is easy to observe that Oyin Olugbile must have drawn deeply from these invaluable lessons in literature. What is especially commendable, however, is the way she has domesticated and recreated such lessons in her debut novel, Sanya. In her novel, Olugbile offers a fresh, creative perspective on the mythology of Sango, one of the most significant primordial beings in the Aborisa religious system.

Sanya begins with a prologue that establishes the historical premise of the entire story. It follows a chronological storytelling style, reminiscent of tales-by-moonlight narratives about the Yoruba pantheon, but with a particular focus on the Orisas. Although fictional, the prologue draws from historical accounts and serves as a creative retelling of the mythological foundations upon which Sanya is built.

The main story introduces us to a sickly child, Dada, born with locs into the family of Ajoke and Aganju, an otherwise ordinary couple in Banire village. The couple, plagued by fear of Dada’s fragile health, desperately seeks more children. After several inquiries and the heartbreak of stillbirths, the eponymous character, Sanya, is finally born. Her arrival disrupts the seemingly ordinary lives of the family. Consequently, the sudden deaths of Ajoke first after childbirth and Aganju months later propel both siblings into a new phase of life with their mother’s twin sister in Aromire village. They gradually move toward fulfilling a prophecy in which they both play crucial roles, though they remain unaware of its significance.

The next time Sanya appears is in Part II, now a fourteen-year-old lanky teenager described as having “sturdier shoulders than her brother. Her arms had small, firm muscle mounds, and her legs, sticking out from her buba and adire shorts, seemed to go on forever”.

This physical portrayal stands in stark contrast to her brother, Dada, who is depicted as “as weak as an okro plant, and anyone could bend him to their will by just applying a little force.” As the stronger and younger of the two, Sanya naturally assumes the role of protector. This sense of duty not only defines her relationship with Dada but also serves as the catalyst for many of the actions and conflicts that unfold in the later parts of the novel.

As the children grow, their differences—particularly their strengths and weaknesses—become more pronounced. What Dada lacks in physical strength, he makes up for with his gift of clairvoyance, though this ability also serves as his greatest vulnerability. He is the more introspective of the two, and we encounter him primarily through his stream of consciousness rather than through direct action.

Sanya, on the other hand, is driven largely by impulse. Her extraordinary physical strength fuels her brazenness, but she remains largely oblivious to her surroundings. Unlike her brother’s reflective nature, Sanya is defined by her actions. This contrast is evident from her first act of “saving” Dada, where the omniscient narrator highlights her personality: “Sanya continued talking, unaware of her brother’s thoughts… Her loud voice disturbing the birds…”. These contrasting traits are gradually deepened as the narrative unfolds, ultimately manifesting in the defining choices and actions of each character.

In many African cosmologies, dreams are understood not simply as psychological by-products but as spiritual experiences. They act as conduits between the human and the supernatural, providing warnings, revelations, or glimpses of destiny.

Oyin Olugbile’s Sanya situates itself firmly within this African paradigm. Both Sanya’s and Dada’s dreams are not abstract psychological states but direct precedents of future realities. Dada’s opaque vision of a rivalry with his sister over a throne foreshadows the eventual conflict that shapes their intertwined destinies. Sanya’s dream encounter with her mother similarly becomes a literal turning point in the novel. In the dream, she is compelled to swallow a stone, which materialises in reality as a consuming, almost invincible strength in battle.

This spiritual empowerment, however, becomes uncontrollable. Sanya’s inability to master her newfound power culminates in the murder of Ropo, her brother’s bully, exposing the double-edged nature of divine gifts. The act disrupts the careful efforts of her aunt, Abike, who attempts to shield Sanya from a prophesied destructive path. Yet, true to the logic of African cosmology, destiny proves inescapable. On the eve of her arranged marriage, Sanya abandons Abike’s plan and flees, stepping into a future which is seemingly unknown, yet already etched into her fate.

After Sanya’s disappearance, Dada struggles with conflicting emotions: “A part of him, some dark part, was relieved that he would no longer be smothered by his sister’s need to protect him… but those feelings were also conflicted by a childish anger that Sanya had broken her promise to always be there for him.” As the novel progresses, however, and he gradually comes into his own—eventually crowned the new Kabiyesi of Banire—he concludes that it is best for his egocentric sister to remain far away, lest she undermine his authority and efforts.

Meanwhile, Sanya’s disappearance marks the beginning of her transformation. She wanders through an unknown path and emerges profoundly changed: “…she was noticeably older and looked fierce, as though well-cooked in the flames of a life she could not remember”.

Her growth, however, extends beyond her physical appearance; she evolves into a formidable warrior. Finding herself in Oluji village, whose king has just been murdered by marauders, she rallies the few remaining warriors and leads them to victory. After months of living among the people and proving her strength, she is crowned king—mistakenly, under the assumption that she is a man due to her masculine appearance.

Both siblings rise to prominence, yet Dada’s determination to avoid his sister Sanya, rooted in the fear of his prophetic dream, inevitably erodes under the weight of destiny. His futile resistance mirrors the Shakespearean insight that human beings are often powerless before larger cosmic forces: “As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods; they kill us for their sport”.

Indeed, Sanya offers a creative retelling of the story of Sango, but with a dynamic focus not only on power but also on the nuances of human emotions and relationships. One such instance is the sibling rivalry between Sanya and Dada.

Because of his physique and frail health, Dada continues to nurse a wounded ego. His sister looks down on him, believing he is incapable of much, but Dada is determined to prove everyone wrong. When he gets the chance to become king, he accepts it as an opportunity to finally demonstrate his worth.

However, Sanya reappears and, despite her earlier promise, reclaims the spotlight amidst the praises of the people of Banire. She, too, is crowned king, and from this point Dada begins to plot her downfall. Sanya, however, blinded by fame and adulation, remains unaware of her surroundings and does not see Dada’s schemes until it is too late. Her fall results largely from her hubris or pride rather than from any preternatural force.

Beyond pride, Sanya’s downfall also stems from her unchecked powers and overreaching ambition. Like Macbeth, she believes she can act without consequence. Her decision to subsume her brother’s kingdom under her control, as well as her refusal to heed Oya’s warnings about the dangers of her relationship with Osoosi, ultimately led to her tragic end

Although this book is undeniably a work of creative brilliance, it is not without its limitations. My first critique concerns the implicit message it conveys about femininity. In an interview with Literature Voices, Oyin Olugbile subtly distanced herself from the claim that she was reimagining Sango through female instincts but rather from a creative lens.

Yet, when gender is at stake, neutrality is hardly possible. While Sanya is nominally identified as a woman, the text offers little to substantiate her femininity. As the narrator observes, “The only hint of femininity about her, [were] mere nubs where breasts should be”. Her physicality and attributes are consistently coded in masculine terms—strength, bravery, and fearlessness.

In contrast, her brother Dada is characterised through weakness, vulnerability, and, at times, effeminacy. This juxtaposition produces a troubling implication: that strength and authority are inherently masculine qualities, while weakness and fragility are aligned with femininity.

Rather than disrupting patriarchal binaries, the novel inadvertently reinforces them, suggesting that power cannot be embodied in a recognizably feminine form. Thus, while Sanya succeeds as a mythological and literary reinvention, and attempts to blur the importance of gender in matters of power (see this excerpt: “If they did not feel that her deeds were more important than her gender, then it was their own failing rather than her problem”), it reinscribes stereotypes it might otherwise have subverted.

Another criticism is the way the Orisa, Esu, is portrayed. In the Aborisa religious tradition, Esu is a trickster god and a divine messenger. As Wole Soyinka points out, people often blame Esu for everything evil, even though he is not evil at all.

In Sanya, however, Esu is shown as exactly that—an evil figure, a disruptor of order, described as one who was rejected in heaven and cast down to earth. All through the novel, Esu appears in dark, menacing terms as the ultimate source of destructive dark power. The issue here is that this repeats a long-standing distortion. By painting Esu as purely evil, the book leans into the Euro-Christian view of Esu, rather than reflecting his true role in Yoruba belief.

Among other things, what makes Sanya such a remarkable work is the way it reimagines an important story in Yoruba mythology, one that deserves to be passed down from generation to generation. But beyond that, its real brilliance lies in its layered portrayal of human personalities and their complexities.

The novel’s ending is not about punishment for wrongdoing or reward for making the right choices. Instead, it holds up a mirror to readers, showing us that binaries—right and wrong, fair and unfair—are often illusions. Sanya is the kind of novel that pushes us to question ideas of partiality, impartiality, fairness, and justice, all through the lens of history, culture, and myth.

It is perhaps this deep grounding in Yoruba history and mythology that earned Sanya a spot on the shortlist for the Nigeria Prize for Literature 2025. And deservedly so. Sanya is not just a book to admire for its beauty; it is a work that should be shared and taught.

Evidence Egwuono Adjarho is a dynamic and evolving creative with a flair for literature and the arts. She finds joy in reading and writing, and often spends her free time observing the world around her. Her interests span a wide range of artistic expressions, with a particular focus on storytelling in its many forms including photography.