This Motherless Land is also a novel about places and the power they hold over who we become or do not become.

By Chimezie Chika

Over the last half-decade or so, there has been, to put it mildly, an explosion of YouTube accounts owned by individuals of mixed-race African origins, who are documenting their peculiar experience of life and the world through videos and vlogs.

Capturing their unusual experiences—the differences in the two or multiple cultures that reside within their blood—gives them many followership, which means more views (in a digital economy where viewership numbers are a vital currency); but also it helps them find like-minded people going through the same things—doing life, as they say.

Many of the more popular individuals in this hyphenated category are Nigerians (to wit: more and more hyphenated, mixed-race Africans are becoming popular on the internet), offspring of marriages and adult partnerships between men and women from Nigeria and other nationalities across the world. The internet has lately buzzed with such identities as Nigerian-Japanese, Nigerian-Indian and even Nigerian-Tajik, amongst others.

I have started with these facts first because it seems to me that there is no better time for Nikki May’s novel, This Motherless Land (currently on the NLNG Prize shortlist), to have emerged than now—at a time when our literature has not even fully started capturing the stories of multi-racial Nigerians. This alone makes May’s novel an immensely important one, even if it is not only about that.

The story of the main character, Funke Oyenuga, in This Motherless Land occurs majorly in decades before the digital revolution, thus she is unable to document her experiences, as many in that cultural and racial in-between do now, which is why often we are jolted and pricked, as the novel shows, by the subtle and overt resentment and racism that people in her position deal with across their dual or multiple cultures.

Back in the 1970s, Funke experiences a sheltered and happy childhood in Lagos (at the LUTH campus), where her Yoruba Nigerian father, Babatunde Oyenuga, teaches in the medical school and her English mother, Lizzie Oyenuga (nee Stone), teaches in a private elementary school.

A terrible accident on the commute to school one morning throws Funke into a motherless state, which changes her life. Losing her brother as well in the same accident is compounded by her father’s unhinged emotional response to her survival.

In the immediate aftermath, Funke is shipped to England, to the town of Somerset, to live with the English side of her family (who had, it is worth noting, disowned her mother years before for marrying a Black man). Upon arrival, Funke, whom her English family chooses to call by her English name, Katherine, is given a cold welcome, chief of all by her Aunt Margot, her mother’s only sister.

As it turns out, Aunt Margot is an eternally resentful and uncompromising racist who treats Funke/Katherine with utmost disdain and flippant incivility, never accepting her at all as a blood relation or even as a human being—a fact she promptly denies when, upon reacting strangely to Kate, her daughter, Liv, asked her if they were racists. To which she promptly replies (in one of the novel’s best instances of gallows humour): “I don’t have a racist bone in my body”.

It is nonetheless easy to see, the deeper we go into the novel, that every bone in Aunt Margot’s body is one of insufferable hatred towards anybody not White and upper class.

In Margot, May has created one of the best villains in recent fiction. Her unrelenting insistence on wrongness, her conviction that her twisted views of things should be the status quo, is almost admirable. It is shocking even when her villainy almost transcends its despicable limits in directly wishing for her own mother’s death so she can inherit and sell off the family estate.

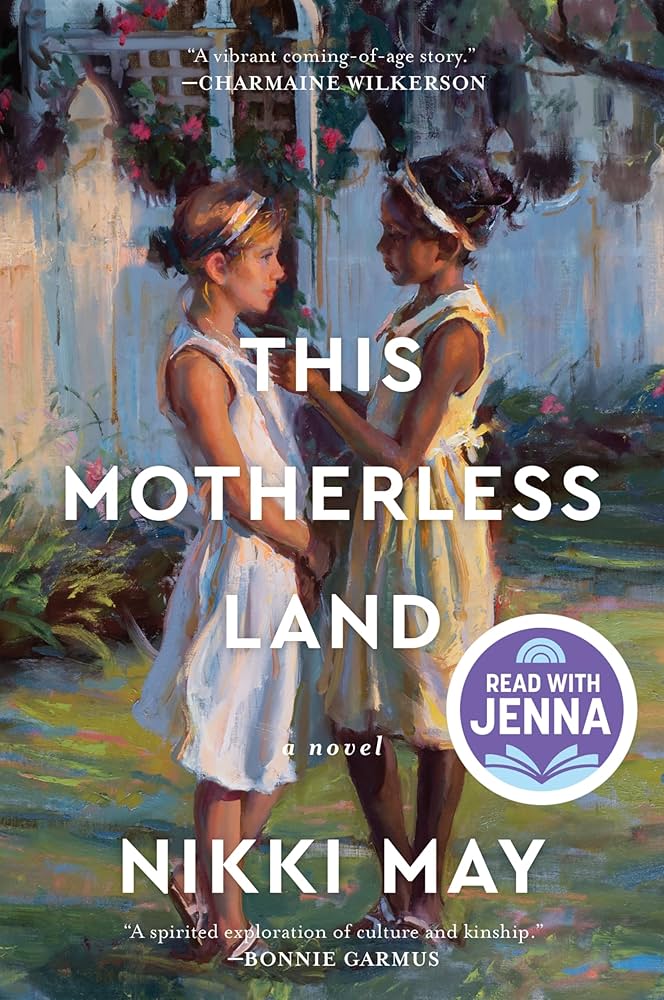

In the late 1970s, when Kate first arrived at the Stones’ estate (named The Ring) as a nine-year-old, having been shipped from Nigeria, the only warm reception she received came from her cousin Liv, Aunt Margot’s daughter, who is more or less her age mate. Together, the girls would develop a close bond even as the other Stones children grow to become entitled, near-clueless adults.

An incident on Kate’s eighteenth birthday, just before she is slated to leave for the University of Bristol on a scholarship to study medicine, puts Aunt Margot into her evil element. She takes away Kate’s British passport (and much of her inheritance), leaving her with only the Nigerian one, and then practically threatens her into returning to Nigeria. Part of the reason for Margot doing this is realising that, baring her and her son, Dominic, every other member of her family loves Kate.

Back in Nigeria, Kate assumes once again the identity of Funke as her now apologetic father tries to make her comfortable amidst Nigeria’s perennial social and infrastructural discomforts. Kate subsequently settles into medical school in Lagos and retraces her Nigerian roots and their own tribulations, which in the end prove far more benign and homely than her English ones.

From early on in This Motherless Land, after Funke arrives in England, the novel settles into an oscillation between a revelatory comedy of manners about family and a Bildungsroman following the coming of age of two girls, Liv and Funke, whose lives are so widely disparate as to be of two different realms. Liv nearly destroys herself in adulthood as she moves through life guilt-ridden over how she and her family had treated her cousin. Some of This Motherless Land’s most poignant sections are those of Liv scraping through a shallow underground of drugs, unsatisfying sex, and temporary jobs—fully intent on self-destruction.

Nikki May tempers the thought-provoking subject of This Motherless Land with admirable humour, although the humour is somewhat reduced by the middle as things get more serious. A pivotal change in tone, in seriousness of purpose perhaps, elevated this novel from an ordinary whimsical tale in the earlier parts to something increasingly remarkable. It grows on the reader.

May’s drawing of characters, her control of the subtleties that make individuals who they are, especially with the passage of years, is masterly. Nikki May is at her best when capturing the confusion and pain of alienated childhood—the frustrations of a child who is caught at the threshold of two worlds, especially one in which isolation is exalted and love is deliberately withheld by bigots who are terrible at playing the game of family.

More than that, May’s story shines through when this alienation is heightened by the awareness that comes from an adult’s realisation that what was overlooked in childhood is often more meaningful than it may appear at first. The trauma that comes from this is played out in Funke’s life, as well as in Liv’s.

The themes that the novel threads through are relevant to the conversations being generated today in a hyper-globalised, multicultural world. One is the constant sense of unbelonging that Kate felt at different times in her life. In short: belonging and unbelonging in equal measure, particularly in the absence of her mother, who would have shielded her from the worst manifestations of those tribulations.

May’s prose captures this alienated state at different points, one of the most acute being the pattern of Funke’s thoughts when she returned to Nigeria: “This was like being nine all over again, dumped in a strange, alien place. She wanted the safety of what she knew”.

Such thoughts create avenues for debilitating self-questioning about one’s own perceived existential inadequacies—being an alien in two cultures, never quite fully blending into each. Individuals like Funke, as we learn both in the novel and in the world of YouTube and TikTok vlogging, often mitigate this sense of unbelonging by means of language, cultural immersion, and online communities, even if physically they still stick out.

Funke finds herself exchanging her names for the different locations and cultures she has links to: In England, she’s Kate; in Nigeria, she’s Funke.

Beyond anything, Nikki May has written a poignant novel about the trials of hyphenated identities; she has written a novel about wrong, forgiveness, and familial indentations in the life of individuals. This Motherless Land is also a novel about places and the power they hold over who we become or do not become.

London/Somerset and Lagos hold sentimental attachments for Liv and Funke because of their rootedness in these places. For Funke, the kinship of Lagos is that of her mother’s perpetually benign presence, even in death. Her search for a home, if home can be one place, is more or less a search for her mother.

In This Motherless Land, May manages to draw us wholly into this sense of rootlessness and the search for a real home. That rootlessness is peculiarly compounded by the ambivalence and alienation of racial and even cultural identity, teaching us that there is no one way to be Nigerian in the multicultural surfaces of this age.

Chimezie Chika is a staff writer at Afrocritik. His short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Weganda Review, The Republic, The Iowa Review, Terrain.org, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Fahmidan Journal, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, and Channel Magazine. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture, history, to art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on X @chimeziechika1