“If anything, I hope that winning the Nigeria Prize for Literature makes my book more visible” – Nikki May.

By Evidence Egwuono Adjarho

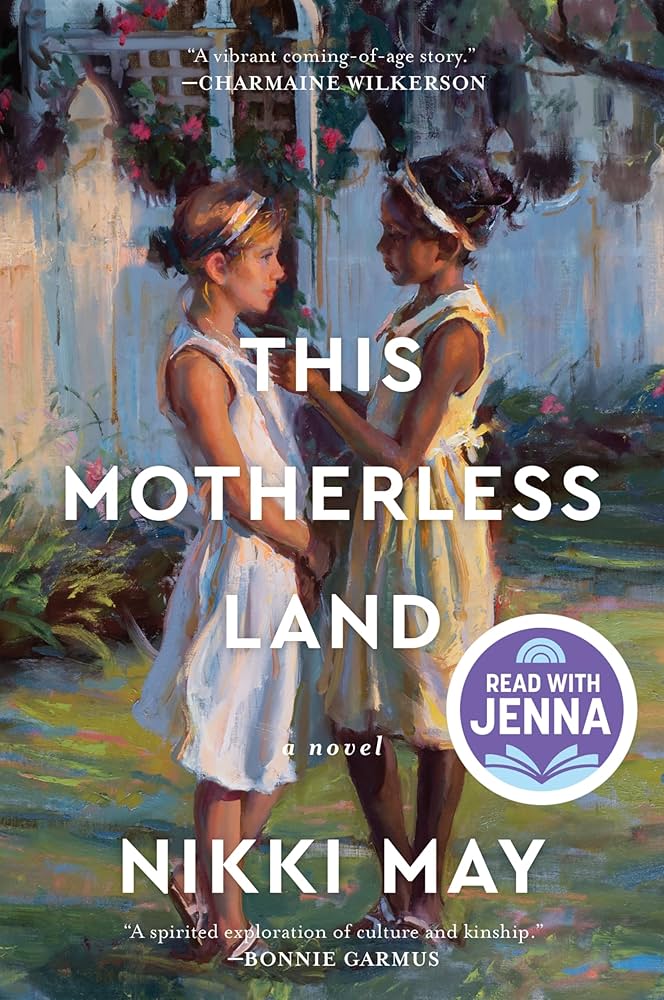

The Nigeria Prize for Literature 2025 released its shortlist of three in August 2025. Each of the selected books was lauded as an exceptional work, distinguished through plotting, characterisation, and an incredible command of language. Among them is This Motherless Land, the sophomore novel by Nikki May, author of Wahala (2022). In his review for Afrocritik, critic and culture writer, Chimezie Chika, notes that Nikki May manages to draw readers wholly into a sense of rootlessness and the search for a real home.

In this interview, Nikki May explores the nuanced perspectives in her book, particularly around themes of identity, belonging, as well as the experiences and influences that have shaped her journey as an author.

Have you always known you wanted to be a storyteller? Or was there a defining moment that drew you into writing?

I have always loved gist from a young age. I love gossip, I love talking. There’s nothing I like better than sitting with my girlfriends and gisting. I have also always loved reading books. I have read a book a week at least since I was ten.

Reading has always been a big part of my life. But it didn’t occur to me that writing could be a profession I would consider. It just never occurred to me. My dad is a doctor, and from before I was five, I was going to be a doctor, although it wasn’t ever said. It was just implicit.

The idea of being an author did not cross my mind. I did go to medical school. I dropped out. I was terrible and would have made a very bad doctor. Then I ran away. I literally ran away from home because my dad was so disappointed in me. That’s when I moved to England at 20.

I worked in advertising, which is as far away from medicine as you can get. But I did a lot of writing as part of advertising – writing pitches or writing adverts. But it still didn’t occur to me that I could write a book. It wasn’t until I was about 55 that I thought: “You know what, this is something you love, you love reading, you love writing, you love telling stories. What is stopping you from doing it? You’ve got nothing to lose by trying. If it works, it works. If it doesn’t work, no one will ever know”. That was the Eureka moment.

After this, I put pen to paper, and that’s when I started my debut novel, Wahala. It took me a long time to think this is something I could do. But with hindsight, I needed that time because I write very much from lived experience. When I was 25, I didn’t have any experience. I didn’t have anything to say.

Although it’s taken me 55 years, I needed that time in order to have the confidence to do it. To write a book, you almost need a balance of impostor syndrome because most writers are convinced they’re not great. But you also need a lot of arrogance because you have something worth saying. It’s like some magic happens when the impostor syndrome and the arrogance just reach a tipping point. It took me 55 years to get to that tipping point.

What does writing personally mean to you?

In some ways, it’s an escape. I find that writing always gives me complete freedom. When I write, I write for myself. I don’t picture a reader. I don’t worry about who’s going to read or judge it. I find writing a very joyful experience and better than therapy.

In both my books, I started thinking deeply and questioning things I believe and why I believe them. By doing such, I found it cheaper and better than therapy – not that I’ve ever had therapy.

Writing is a way of exploring, digging, and traveling in your mind. I love characters. My Wahala girls are still walking around in my head. Funke and Liv are still walking around in my head. They always feel real to me. So I find writing a real escape.

Every writer faces criticism. What has been the toughest negative criticism you’ve received, and how did it affect you?

I do read most of my reviews. I do even go on Goodreads, although lots of authors say “do not go on Goodreads”. But I do because it’s important to listen to what people say. In advertising, you have to get feedback.

I’ve got quite a thick skin. The trick, for me, is not to take it too seriously. If you believe all the good reviews, your head will grow so big that you won’t be able to walk around your own house. On the flip side, if you believe all the bad reviews, you’ll be completely depressed, and you’ll never go out again. There’s a case of being balanced about it.

Obviously, some of them really upset me. But the one that really hurt me was with Wahala and not This Motherless Land. Somebody wrote a review saying this girl [Nikki May] has never been to Nigeria, and if she ever went to Nigeria, Nigerians would beat her. I was actually going to my dad’s birthday the following week. I thought, “How dare you say I’ve never been to Nigeria?” I was made in Nigeria. I lived in Nigeria from when I was six months old to when I was 20. I go back to Nigeria every single year, so how did she dare to lay such a claim?

I did my research and found out the person who said this had never been to Africa, talk less of Nigeria. That was the worst one, and it really pained me. But now I just look back and actually feel sorry for the person.

From your perspective, what would you say is the biggest challenge that comes with being an author?

It’s actually quite exposing. I’ve worked in advertising in my life and used to presenting, selling ideas, and used to being in a room full of people and telling people what I think. But when you are an author, it becomes really personal. It’s almost true that these books become your babies, and my books are quite personal.

This Motherless Land, particularly, is a very personal story, and I draw very much from my own experiences. And you worry about how much of yourself has been exposed. Some people, I guess it’s social media, feel that they can actually tag you.

It takes a thick skin not to take anything personal, which is why I am glad that I came into the career at my old age. Because at 20 or 30-something, I am not sure I could have dealt with the exposure, good or bad. But now, it doesn’t really matter to me.

Reading taste often evolves with time and experience. What kinds of books did you read growing up, and what do you find yourself reading now? What has changed?

I grew up in the 70s-80s in Lagos, and books were in hard supply. We didn’t have the bookshops available now. In fact, there was only an academic bookshop, and so the only books you were getting there were math books and science books. That wasn’t what I wanted.

I read whatever I could get my hands on. A friend of mine had all of Eunid Blyton, and I would borrow all of these books. From reading those books, I actually thought that England was like what was depicted in Eunid Blyton’s.

When I came to England, I was disappointed to find that it wasn’t the books I had read. The other thing is that because books were like currency, I read a lot of things that were age-inappropriate. I had my Mills & Boons days when at Queen’s College we exchanged these books and they would fit perfectly in our pinafore pockets. I must have read about 300 Mills & Boons in my life back in the days when I was a teenager. But your taste evolves.

In England, I discovered bookshops, I discovered crime. I love crime. I love thrillers. I read a lot of those. I remember one book that changed my life, and changed the way I see things. It was A Waiting To Exhale by Terry McMillan, and it was the first book I read where I felt seen. It has three black women in it, and they’re leaving sassy lives, dating, and working. I felt it was a book about people like me.

Half of a Yellow Sun (2006) was another book that touched me a lot because I know about the Biafran War. My father was a medic in the war. But I’d never really thought about it. Half of a Yellow Sun gave the human side of that war and really made me realise what a big impact the war had on many lives. Now I need pretty much anything. I read literary books, thrillers, and psychological thrillers.

I’m not big on fantasy, and I don’t read a lot of fantasy. I’ve tried, but I just don’t have that suspension of disbelief for fantasy. One of the best things about being an author is that you get sent advanced copies. I read anything, and if I am not feeling it, I shelf it.

Your title is striking and layered. Without reading the book, one can tell that it touches on themes of identity and belonging. Could you walk us through how this title came about, and what significance it holds for the book?

The title came after the book was finished. When I started writing the book and when I pitched the book to my publishers, it was called “Brown Girl in the Ring”, and it was a story all about Funke. The house was called The Ring intentionally, so I could use that song. It was very much about Funke coming from Nigeria to England. But characters have this annoying habit of doing what they want and not listening to your perfectly drawn-out plans.

When I got to the end of the first draft, I realised that it was not just about Funke but about Liv. But more importantly, it was about their mothers. I killed Funke’s mother, Mrs. Lizzie – and this is not a spoiler, really– in chapter 1, but her ghost or her presence lingers through this book. It’s almost a thread that runs through the book’s very end.

Liv’s mother was a terrible mother who was alive, while Funke’s mother was wonderful but dead. But they both have such an impact on the choices and the trajectory of their children’s lives. When I finished my fourth draft and I finally got to the stage where this is the story and this is how I wanted to tell it, my editor said we couldn’t call it Brown Girl in the Ring because it didn’t capture the essence of the book.

We spent ages brainstorming. Then, suddenly, I woke up one day and I thought, this is it. It’s This Motherless Land. It was a proper Eureka moment, and my editors immediately approved it. It’s a much better name than “Brown Girl in the Ring” because it’s encompassing and has more layers and nuance.

People write for many reasons—whether didactic, for entertainment, or to share culture. But literature always evokes powerful emotions. For you, what was the experience of writing This Motherless Land like and what is the importance of sharing this story?

In some ways, I was born to write this book. It is really personal, and a lifetime of code switching between Nigeria and England has made me almost obsessed with identity and belonging and what constitutes home. These are things that have been on my mind pretty much all my life. I’m a champion of code switching. I’m coming to Lagos in two weeks for this award, and as I step off the plane, I know I will become more Nigerian. I will become louder. As soon as I step off the plane [to England], I will become quiet and slightly more reserved.

This lifetime of code switching, of belonging one minute and feeling like I don’t belong the next minute, is sometimes concrete and other times elusive. That has made me obsessed with identity. It’s taken me almost all my life to feel that I’m not half English and half Nigerian. I am wholly English and wholly Nigerian.

These were all things I wanted to put into the book. I think that when you’re writing about nuanced subjects like race, privilege, and prejudice, it’s best if you approach it with brutal honesty. I know what prejudice feels like. My Oyinbo grandparents from my maternal side wanted nothing to do with me or my siblings purely because we were the wrong colour.

I also know what privilege is because I’ve lived a pretty privileged life. I had an almost idyllic upbringing in LUTH with my mom and my dad. I’ve had a great education. I have had both privilege and I’ve been prejudiced against. That puts me in a position where I can write about these things with some nuance. I’m in a position where I can see what’s wonderful about both my homes.

I can look at Nigeria, and I can see the wonderful things. But I can see what’s wrong. And I can look at England and see the wonderful things, but also see what’s wrong. I really wanted to write a nuanced book that wasn’t black or white, that wasn’t right or wrong.

One that showed that these things are much more complicated than they appear to be. It was a big book to write; it was a lot to wrestle with. For the 90,000 words that end up in this book, I wrote 200,000. To get it down was difficult because I always have too many things. I’m trying to do too many things.

Yet, when I write, all I want to do is entertain. I want my reader to be engaged and want them to turn the pages. I want them to dance, and I want them to cry. There’s also trying not to make sure that things are sitting on top. I like things to be underneath. I want my characters to tell their story.

I want my readers to think, to take more out of it than just the gist. But my main job is to make sure that the reader is entertained. But obviously, I want more than that. I want them to think about themselves and to question their own prejudice. I want them to own their own privilege and love my homes. At least once a week, I get a DM on social media from someone saying I made them want to visit Lagos. That just makes me happy.

Funke, your protagonist, struggles with belonging but eventually accepts that she was never meant to blend in. Using her journey as an analogy, what is your own perspective on identity and belonging?

The other thing that this book is is a love story, and there’s that phrase that I use in the book, “Eniyan l’aso mi”. There is even a song by King Sunny Ade. But it basically means that people are my covering and they are what make me what I am. Where I’ve come to is that you belong where the people you love are, and those people can be in ten places. But it’s people that you belong to rather than places. It’s more about belonging in hearts rather than on land.

That’s been my journey. I can belong here and I can belong there. When I’m here [England], Nigeria is always home, and when I am in Nigeria. I’ll talk about going home because I have two homes, and that’s where I’ve come to in my journey. A bit like Funke because her journey is similar to mine.

You have mentioned that your novel draws from your personal experiences. How did you draw the line between agency in the book and authorial intrusion?

I used my experience to, hopefully, make things authentic, but it’s complete fiction. I mean, I killed Funke’s mom, but my mom is alive and well. My experiences inform my characters, but it is fiction. Liv’s party days in London were very much influenced by my own party days. But Liv’s are dialled up.

You use your experience to make your books feel authentic, and what your characters are doing is believable. But apart from that, the joy of writing is to design these lives of people; it’s to decide what’s gonna happen to them and when. And if I build characters that I believe in, then they have agency.

In some ways, if I build my characters correctly, so that they actually have flesh and bones, they have agency. I’ve spent much time building my characters. I mean, way too long. Although I say Funke’s based on me, she isn’t. Funke is much different from me and more of a version my dad would have loved. I influenced her, but she’s very much her own person.

Your book has been shortlisted for the NLNG Prize. What does this recognition mean to you, both personally as an author and for the story you’ve told?

When Narrative Landscape entered me for the prize, I was happy. I felt that was an acknowledgement that they think my book is good enough. When it was longlisted, I screamed. I mean, this is a huge prize. This can be said to be the African Booker, and authors want nothing more than the acknowledgement, affirmation, and bragging rights.

Being shortlisted has just blown my mind because to be shortlisted for such a personal book in my fatherland gave me all the feelings. The first thing I did was phone my dad so that he could finally forgive me for dropping out of school. He was over the moon, and he’s coming to the party. This is a dream come true for me, and I’ve decided I’m already a winner.

Some past NLNG Prize winners have been accused of becoming complacent writers or disappearing from the literary scene. If you were to win, what would that victory look like for you?

It’s a difficult question because I don’t know. I mean, I am already halfway into book 3, and I cannot see anything stopping me from writing it. Because as I said to you, when your characters become real, they insist you write their story. I hope that winning this prize will be the rocket fuel I need to get to the end of book three. But it’s difficult. You just don’t know.

Sometimes, the pressure of expectation can be a block. I honestly don’t know. I would say I’m glad it’s not my debut. I’m glad I’ve had one go round. I’m glad I’m 60. Being an author is something that happens in verse. Most of the time, I’m just Nikki May living my life.

Right now, I’m doing interviews and appearances because I am an author. But in three weeks time, I’ll go back to being Nikki at home with her dogs, cooking pounded yam on the weekend, watching Mad Men on telly. You know, I’ll just go back to my normal life. I hope I will still write my third book. If anything, I hope that winning the Nigeria prize for literature makes my book more visible.

You wrote your first book in 2022 and your second book in 2024. What’s your next project? Can we get a glimpse?

I’ll try, because you know that until I’ve written the first draft, I don’t actually know what my book is about. But it has three women, and at the moment, my latest ism is ageism. I turned 60 in April, and 60 is this thing for a woman where you become slightly invisible.

As well as ageism, we have youngism, where we are horrible about young women, and we’re horrible towards older women. I vividly remember being around 35 when you’re at that “are you gonna have kids, why haven’t you had kids? What’s happening with your life?” phase.

It’s almost as if there’s no good time to be a woman. Whatever phase you are in, somebody has an opinion on what you’ve done wrong and what you should be doing or how you’re failing. What they should be doing is fighting the system rather than fighting each other. I am halfway through and my characters are doing what I don’t tell them to do; they’re going here and going there rather than following my meticulously laid plan. But I hope to have a first draft by the end of the year, and then I’ll work out what this story is and write it all over again.

What’s that unpopular opinion you have?

The world has become this place where you’re afraid to say things in case you get cancelled, which is quite frightening. You know, if you say this and people don’t agree, they can’t just disagree anymore.

They have to find a reason to cancel you, and you’re not allowed to have certain opinions. My unpopular opinion is that we should be allowed to have opinions, and we shouldn’t cancel people just because we don’t agree with them.

Finally, what three African books do you think everyone should read, and why?

Everybody in the whole world should read Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I love this book. It’s an important book. I’ve read it probably 3 or 4 times. I’ve pressed it into many hands. It taught me things I thought I should know but didn’t know. What I love about it is it just shows the stupidity of war and the effects on human beings.

For the second book, when I was in Lagos for my Wahala launch, I was given Nearly all the Men in Lagos are Mad (2021). I really loved Nearly all the Men in Lagos are Mad. I barely read short stories, so this is one big exception. Damilare Kuku’s titles are just banging. I want her to name my next book. She writes very cleverly, mostly from a point of view that I wouldn’t be able to write in. You know, that almost second-person point of view. It’s really hard to do.

The third book is actually non-fiction. It’s called Africa Is Not a Country (2022) by Dipo Faloyin. It’s in little sections, and one of those books you can pick up and drop off any time. It should be in every school’s curriculum. Not just in Nigeria, but everywhere in the world.

Because lots of the stories about Nigeria, about Africa, are unnuanced. You hear about Boko Haram, or you hear about poverty, or you hear about violence, or you hear about 419. They’re just flattening and reductive when there’s much about us. This book really helps educate the ignorant about what Africa is and what we do. It’s a lovely book. It’s funny, intelligent, and I recommend that everyone read it.

Evidence Egwuono Adjarho is a dynamic and evolving creative with a flair for literature and the arts. She finds joy in reading and writing, and often spends her free time observing the world around her. Her interests span a wide range of artistic expressions, with a particular focus on storytelling in its many forms including photography.