Across generations, these films have returned to the same core questions: Who are we? What do we believe? How do our beliefs and traditions shape the future we build?

By Joseph Jonathan

For decades, Nollywood has drawn deeply from African spirituality—one of its richest wells of storytelling. From the VHS boom of the 1990s, when lurid tales of rituals and juju filled video club shelves, to today’s lavish epics streaming on Netflix, Nigerian filmmakers have consistently turned to myth, faith, and folklore to explore how unseen forces shape human destiny.

Across generations, these films have returned to the same core questions: Who are we? What do we believe? How do our beliefs and traditions shape the future we build? Whether through Yoruba classics preserving oral traditions or sleek New Nollywood films reframing indigenous myths for a global audience, cinema has become a space where spirituality is not only performed but interrogated.

Spirituality can mean different things to different people. In this list, it refers broadly to traditional beliefs, rituals, and cosmologies but also includes films exploring faith, divine presence, or spiritual transformation in everyday life. A film doesn’t need to feature literal gods, spirits, or magical powers to qualify; what matters is that it engages with questions of morality, destiny, or unseen forces in ways that resonate with African worldviews.

These stories are never just about magic or the supernatural. They are about morality and greed, power and corruption, politics and identity.

In this list, Afrocritik presents 30 Nollywood films that explore African spirituality and tradition, tracing how the industry has reflected, distorted, and reimagined indigenous belief systems—haunting the screen, guiding narratives, and shaping collective memory across generations.

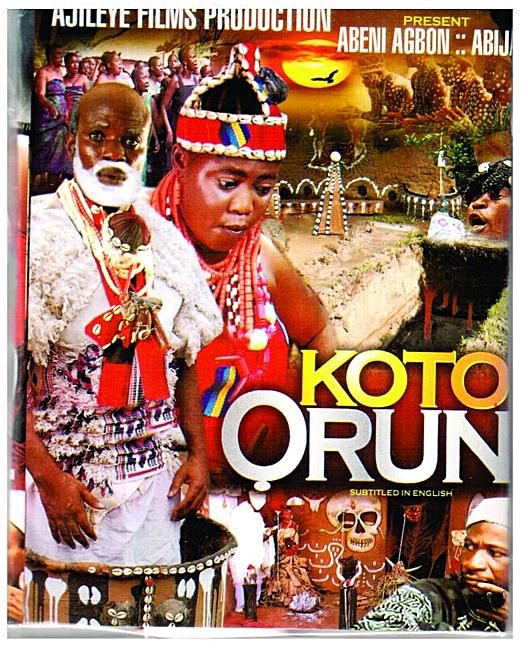

Koto Orun (1989)

One of the earliest Yoruba spiritual films, Koto Orun, cemented Alhaji Yekini Ajileye’s reputation for dramatising the clash between humans and the spirit world. The film showcased witches as both terrifying and ever-present forces in daily life, balanced against the protective power of “aje funfun” — the white witches.

Its chilling imagery and atmosphere left a mark on audiences, with lead actress Margaret Bandele Olayinka, popularly known as Iya Gbonkan, later claiming she suffered real-life spiritual attacks after the role. The film remains a milestone in Yoruba cinema’s engagement with indigenous spirituality.

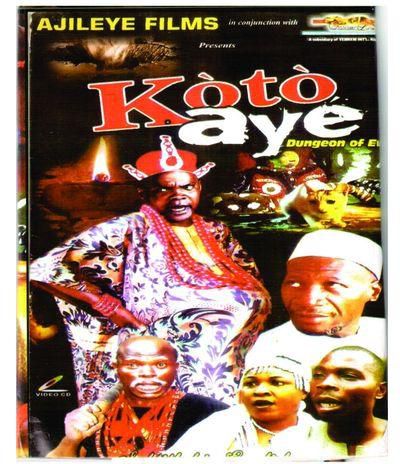

Koto Aye (1990)

Also directed by Alhaji Yekini Ajileye, Koto Aye built on the legacy of Koto Orun and further cemented Yoruba-language cinema’s role in preserving indigenous narratives of spirituality.

A fever dream of witches, blood rituals, and bone-rattling sound effects, the film featured the unforgettable Abeni Agbon, a menacing witch whose cruel acts became the stuff of folklore. Its infamous witch dance sequence — women clad in flowing black, moving to pounding drums — unsettled an entire generation, while its haunting soundtrack lingered in popular memory.

The film’s aura was so chilling that when some of its cast later died in real life, rumours spread that they had been claimed by the very spirits they embodied on screen. For many Nigerians, Koto Aye was more than a movie — it was a cultural haunting that blurred the line between entertainment and lived belief.

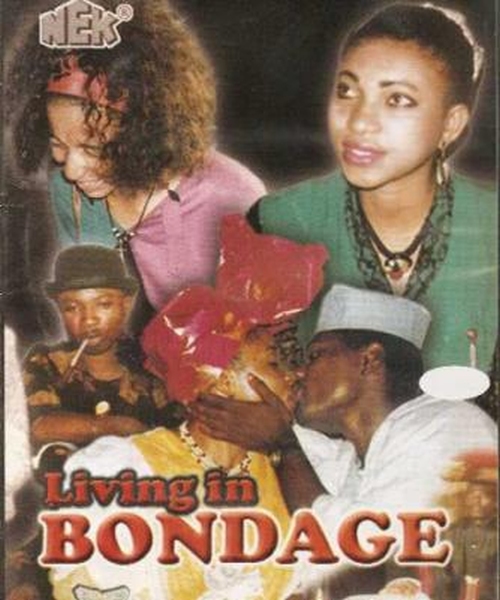

Living in Bondage (1992)

Considered the film that gave birth to what is now known as Nollywood, Living in Bondage tells the story of Andy Okeke, a man who sacrifices his wife in exchange for wealth. The film’s success established ritual-themed storytelling as a defining feature of the industry for years to come.

Beyond its occult theme, Living in Bondage was the first Nollywood film subtitled in English, allowing audiences across Nigeria’s diverse ethnic groups to engage with it. It not only launched Nollywood’s home-video era but also set the tone for its early obsession with greed, power, and the dangers of juju.

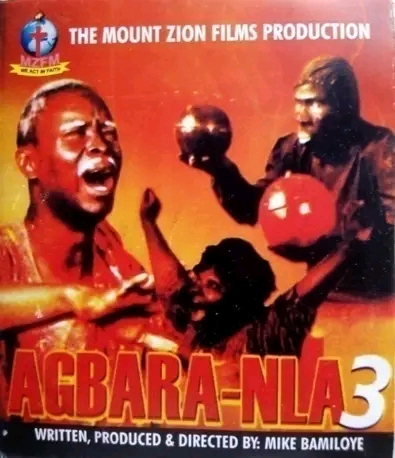

Agbara Nla (1992)

Directed by Mike Bamiloye, Agbara Nla paved the way for the wave of Christian drama films that would later dominate Nigerian home video. The story of a village under the grip of dark forces, it terrified audiences with its vivid depictions of spiritual warfare — most memorably the roar of a demon-possessed character declaring “Ayamatanga” (later explained as “I Am At Anger”), a phrase that quickly entered Nigerian pop culture as shorthand for evil.

The film’s impact was immense, propelling Mount Zion Film Productions — founded in 1985 but relatively obscure until then — into national prominence. For years afterwards, Christian dramas were so synonymous with the group that many viewers simply called them “Mount Zion films”.

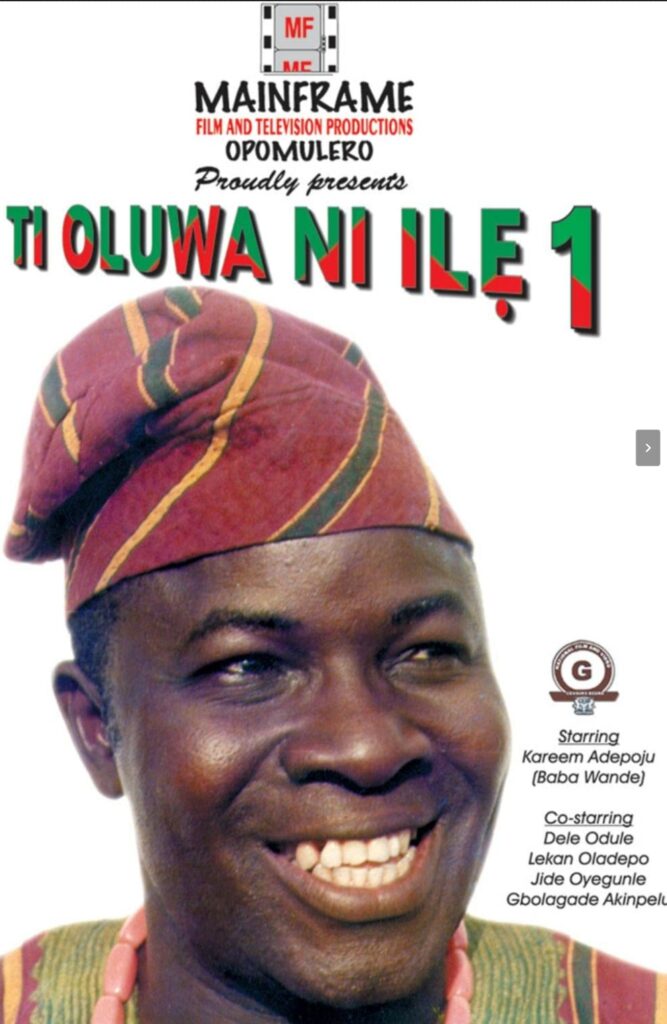

Ti Oluwa Ni Ile (1993)

Widely regarded as one of the foundational films of Yoruba-language cinema, Ti Oluwa Ni Ile (meaning The Land Belongs to God) is a morality tale that weaves spirituality, tradition, and social commentary.

Directed by Tunde Kelani and scripted by playwright and actor, Alhaji Kareem Adepoju (Baba Wande), the film tells the story of corrupt chiefs who sell sacred land meant for communal use to greedy developers. Their betrayal of tradition unleashes a chain of spiritual consequences, reminding audiences that the land and its heritage are not commodities but sacred trusts.

The film’s success spurred two sequels and cemented Kelani’s reputation for blending folklore with pressing social realities. Beyond its entertaining storytelling, Ti Oluwa Ni Ile is an indictment of corruption, greed, and the erosion of cultural values, showing how disregard for tradition leads to both moral and spiritual decay. It remains a classic example of how Yoruba cinema used spirituality not only for spectacle but also as a means of community accountability.

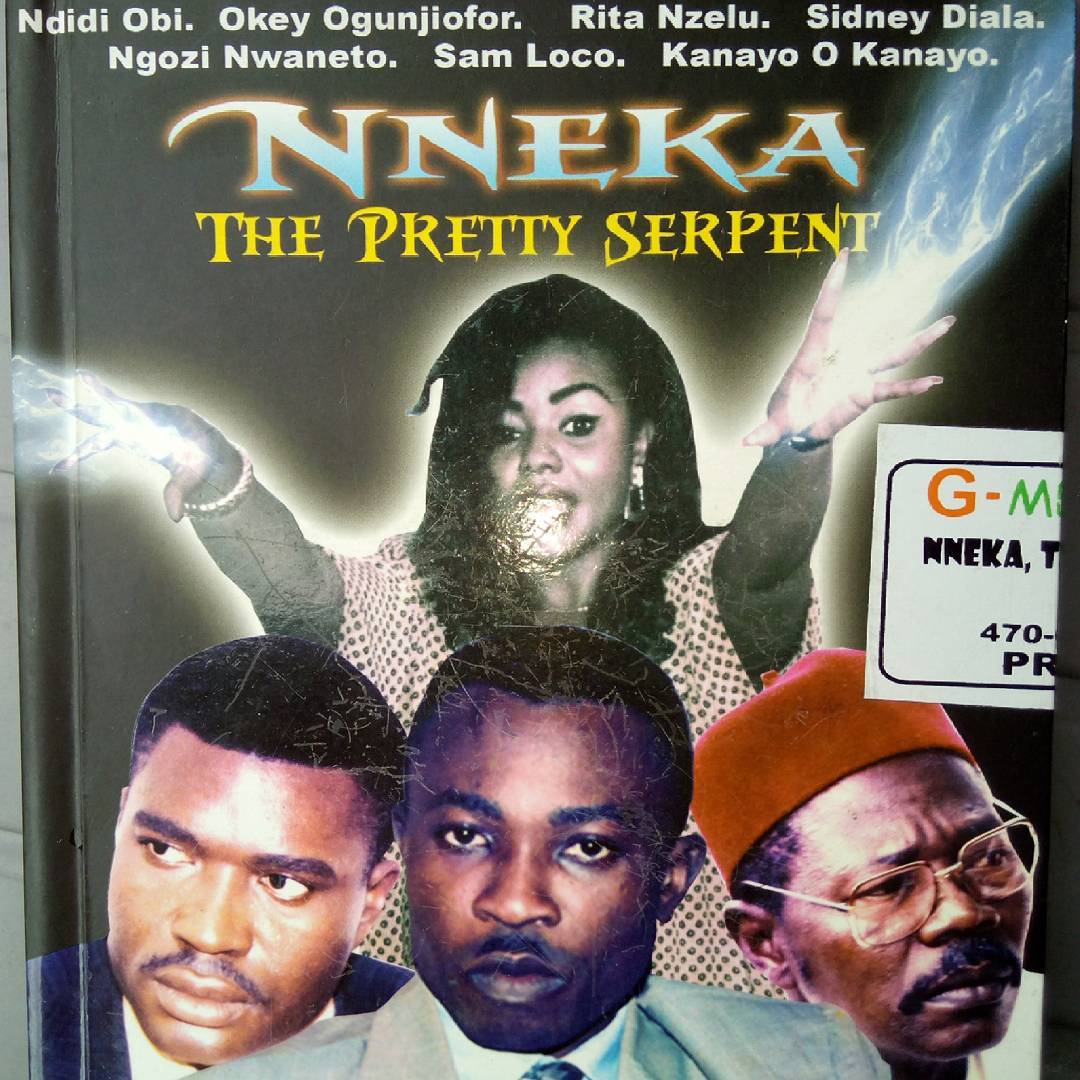

Nneka the Pretty Serpent (1994)

A mysterious woman with supernatural powers who seduces and destroys men, Nneka the Pretty Serpent blended melodrama with myth to become one of Nollywood’s most unforgettable supernatural tales.

The story traces Nneka, a young woman dedicated at birth to a river goddess by her desperate mother. Gifted dark powers, she uses beauty as a weapon, luring wealthy men to their doom. The film’s chilling mix of folklore and morality not only terrified audiences but also popularised the “femme fatale spirit” trope, inspiring a flood of “spirit wife” movies throughout the 1990s.

For many viewers, the takeaway was stark and memorable: if an impossibly beautiful stranger appears out of nowhere, she’s probably not human.

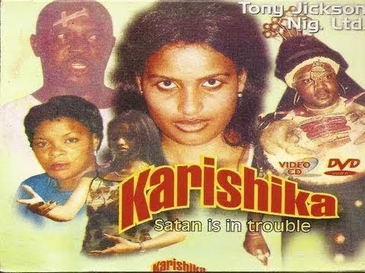

Karishika (1996)

Few Nollywood films have etched themselves into the national psyche quite like Karishika. With its unforgettable soundtrack—“Karishika, Queen of Demons!”—this cult classic brought pentecostal moral panic and supernatural horror to the big screen in a way that thrilled and terrified audiences.

Beyond its eerie soundtrack and outlandish special effects, Karishika cemented Nollywood’s fascination with Christian demonology fused with indigenous fears. Its central warning still resonates: temptation may dazzle in glamour, but it ultimately leads to destruction.

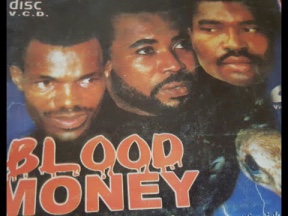

Blood Money (1997)

Directed by Chico Ejiro, Blood Money is a chilling thriller that captured the anxieties of 1990s Nigeria, when economic hardship, ritual killings, and sudden wealth dominated public discourse.

The story follows Mike (Zack Orji), a desperate man who reconnects with his wealthy old friend, Collins (Kanayo O. Kanayo). Collins introduces him to a secret cult called The Vultures, led by a supernatural entity known as the Great Vulture. In exchange for loyalty and blood, the cult promises unimaginable riches.

When asked to sacrifice those closest to him, Mike offers up his wife and mother. But their restless spirits drive him into madness, pushing him to commit a string of ritual murders in a bid for peace.

With its mix of horror, greed, and supernatural terror, Blood Money became a defining film of the era, cementing Nollywood’s reputation for dramatising society’s darkest fears and turning them into unforgettable screen nightmares.

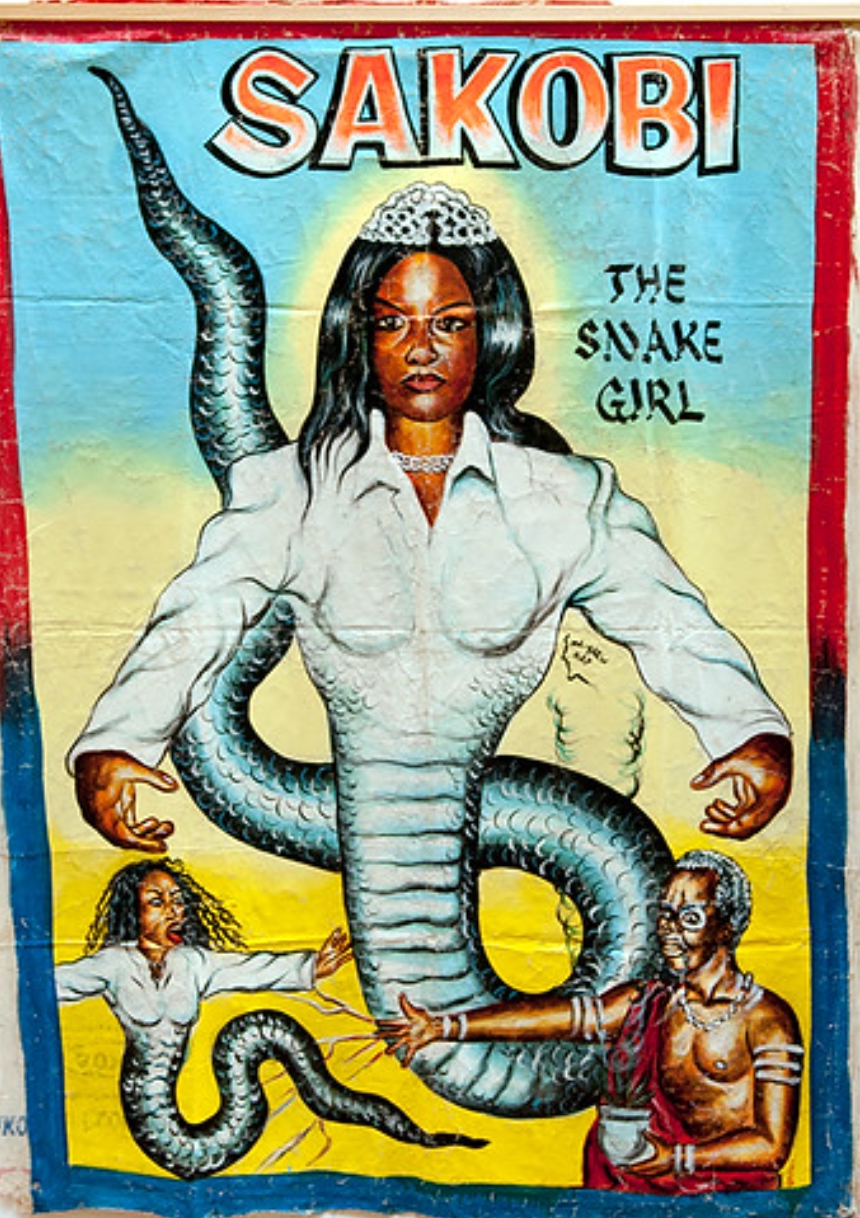

Sakobi: The Snake Girl (1998)

Directed by Zeb Ejiro, Sakobi: The Snake Girl is one of the enduring classics of Nollywood’s “juju cinema”, where folklore and morality collided on screen.

The story follows Frank Davies, a desperate man lured into the cult of the Mighty Serpent goddess through the mysterious Sakobi. Promised wealth and power, he is instructed to sacrifice his only daughter, Hope, and abandon his family to marry Sakobi.

If Nneka the Pretty Serpent introduced the archetype of the femme fatale spirit, Sakobi perfected it—fusing seduction, greed, and the supernatural into a cautionary tale about the devastating price of spiritual bargains.

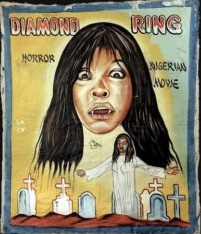

Diamond Ring (1998)

Tade Ogidan’s Diamond Ring tells the chilling story of Chidi, a university student who, in a reckless act of bravado, steals a ring from the corpse of a wealthy woman. The theft awakens her vengeful spirit, unleashing a series of terrifying hauntings that torment him and his friends.

What set Diamond Ring apart was its fusion of campus drama with supernatural horror. At a time when Nollywood’s occult stories often revolved around ritual wealth and greed, the film warned against youthful recklessness and the dangers of disrespecting the dead.

Its mix of modern student life and age-old spiritual dread expanded Nollywood’s supernatural template, making it one of the most memorable horror films of the late 1990s.

Samadora (1998)

Directed by Andy Amenechi, Samadora is a supernatural thriller centered on a mysterious marine spirit who preys on promiscuous men. Tricia Esiegbe stars as the titular Samadora, a water goddess who lures a married man (Charles Okafor) into a dangerous pact, threatening his union with his wife (Omotola Jalade Ekeinde).

The film blends horror, folklore, and moral cautionary tales, with standout performances from Ernest Asuzu, Emeka Ike, Vivian Metchie, and Enebeli Elebuwa. Known for its chilling atmosphere and unforgettable climax—where Omotola’s character urges her husband to “piss on her(Samadora)” to break free—Samadora remains one of the most talked-about Nollywood occult classics of the 1990s.

Captives (1998)

Directed by Ndubuisi Okoh, Captives tells the story of Nick (Bob-Manuel Udokwu), whose father (Alex Usifo) is a devoted member of a powerful cult. Groomed to inherit his father’s position after his death, Nick is pressured to pledge allegiance to the society. But when he refuses, the cult unleashes relentless torment, forcing him into a battle between personal conviction and the dark legacy of his bloodline.

Captives explores how tradition, inheritance, and secret rituals intertwine, revealing the weight of generational obligations and the dangers of resisting entrenched occult power. Like many Nollywood films of the 1990s, it uses the language of African spirituality to dramatise the tension between family duty and personal freedom.

Full Moon (1998)

Directed by Chico Ejiro, Full Moon is a wild Nollywood supernatural tale that predates Western superhero cinema with its own “mutant” heroine, Lucy (Regina Askia). Born under a full moon, she develops extraordinary powers tied to the lunar cycle. As she grows, Lucy discovers her abilities while confronting the men responsible for her parents’ deaths, using her powers to exact justice in ways both spectacular and terrifying.

The film combines occult themes, moral reckoning, and supernatural spectacle, portraying the full moon as a literal and symbolic source of spiritual power. With over-the-top effects, vengeful magic, and ritualistic confrontations, Full Moon is an unforgettable example of how 1990s Nollywood blended African spirituality with heroic narratives, creating a uniquely local take on cosmic justice.

Igodo: The Land of the Living Dead (1999)

At a time when Nollywood was dominated by low-budget melodramas, Igodo stood out as a rare fantasy epic. The film follows seven warriors on a perilous quest into the evil forest to retrieve a mystical sword—the only weapon capable of saving their cursed village.

Rooted in Igbo mythology and rich with traditional lore, Igodo offered audiences a cinematic adventure that felt both grand and deeply indigenous. Its success not only cemented its place as a classic but also proved that Nollywood could embrace epic storytelling without losing touch with African spirituality.

By blending myth, spectacle, and moral lessons, Igodo paved the way for later historical and fantasy dramas that leaned boldly into local cosmologies.

End of the Wicked (1999)

Produced by Helen Ukpabio and directed by Teco Benson, End of the Wicked is an evangelical horror film that thrust witches, demons, and spiritual warfare onto Nollywood screens in graphic, unsettling detail. The story follows a coven led by Beelzebub, who unleash torment on families and recruit new members—including children, lured with enchanted puff-puff—until a pastor (played by Ukpabio herself) rises to confront them.

Low-budget yet strikingly effective, the film became wildly popular, demonstrating how Nollywood could turn basic ideas into gripping horror through sheer conviction. But its cultural aftershocks were just as powerful as its scares: the film helped fuel a wave of child-witch hysteria in Nigeria, leading to real-world witchcraft accusations and abuse.

End of the Wicked epitomised Nollywood’s pentecostal era of the 1990s, when cinema doubled as a pulpit, staging spiritual battles where good and evil clashed not just on screen, but in society at large.

Eran Iya Oshogbo (1999)

This folkloric tale of supernatural justice illustrates how Yoruba storytelling blends morality, myth, and spirituality. Directed by Ajileye, the film follows a grandmother whose deep attachment to her goat sparks fear and suspicion. Anyone who dares harm the animal suffers terrible consequences, until it’s revealed that the goat is, in fact, a human trapped in animal form.

Starring Madam Grace Oyin-Adejobi as the formidable matriarch, alongside Dele Odule and Ronke Oshodi Oke, Eran Iya Oshogbo left such a cultural imprint that to this day, many Nigerians feel uneasy around black goats.

Saworoide (1999)

Directed by Tunde Kelani, Saworoide is a seminal Yoruba film that blends political allegory with rich traditional spirituality. The story follows the tyrannical reign of a corrupt king in the fictional town of Jogbo, where the sacred talking drum (saworoide) plays a central role in enforcing justice and maintaining the balance between rulers and the people.

The film intricately weaves Yoruba customs, rituals, and the belief in ancestral and spiritual authority into its narrative. Through its depiction of kingship, ritual punishments, and the consequences of breaking sacred laws, Saworoide underscores the enduring power of tradition and spirituality in governing society.

Its cultural resonance and moral depth have made it a cornerstone of Yoruba cinema, celebrated not just for storytelling but for preserving indigenous values and practices on screen.

The Figurine (2009)

Kunle Afolayan’s The Figurine tells the story of two friends whose lives are forever altered after they discover Araromire, a mystical figurine said to bless its possessor with seven years of fortune—followed by seven years of despair. Rooted in Yoruba mythology, the film transforms an age-old cautionary tale into a sleek, modern thriller, showing how traditional beliefs still cast long shadows in contemporary life.

Stylish, haunting, and deeply spiritual, The Figurine bridged the old and the new—reviving Nollywood’s fascination with indigenous mysticism while ushering in the New Nollywood era of ambitious storytelling and higher production values.

God Calling (2018)

Directed by Bodunrin “B.B.” Sasore, God Calling reimagines spiritual awakening in the context of Nigeria’s digital age. The film follows Sade (Zainab Balogun), a grieving woman battling despair after a personal tragedy.

Her life takes an unexpected turn when she begins receiving mysterious, God-like messages through her mobile phone. These supernatural “calls” guide her on a redemptive journey of faith, healing, and self-discovery.

Unlike the demon-centric horror of 1990s Nollywood or the myth-driven epics of earlier decades, God Calling brings spirituality into a sleek, contemporary setting—using technology as a metaphor for divine connection. Its ambitious production values, striking visual effects, and modern urban backdrop reflect Nollywood’s ongoing attempt to speak to a generation negotiating both tradition and modernity.

More than just a faith-based drama, the film represents Nollywood’s evolving relationship with religion and spirituality, showing that divine encounters can be imagined not only in forests, shrines, or churches, but also in the buzzing digital spaces of 21st-century Nigeria.

Juju Stories (2021)

Directed by the Surreal 16 collective—C.J. Obasi, Abba T. Makama, and Michael Omonua—Juju Stories is a three-part anthology that reimagines how traditional spirituality intersects with everyday urban life in Lagos.

Each director contributes a standalone tale: Omonua’s Love Potion probes the desperate use of charms to force romance; Makama’s Yam unravels the eerie fallout when a man picks up money off the street; and Obasi’s Suffer the Witch explores friendship, obsession, and witchcraft in a university setting.

What makes Juju Stories remarkable is its quiet normalisation of juju. Instead of the flamboyant effects and overt moralising of Nollywood’s 1990s “juju cinema”, the film treats spiritual practices as subtle but ever-present forces within the fabric of modern life—shaping decisions around love, money, and loyalty.

This shift positions Juju Stories as a bridge between eras: it inherits the fascination with indigenous spirituality from old Nollywood but filters it through the art-house lens of New Nollywood, with moody visuals, minimalist pacing, and layered storytelling. In doing so, it reframes African spirituality not as a spectacle of fear, but as a complex cultural logic still relevant in the present.

The film’s resonance was international as well—Juju Stories won the Boccalino d’Oro Award for Best Film at the 2021 Locarno Film Festival—cementing its place as both a continuation of Nollywood’s spiritual tradition and a bold reinvention of it.

The Blood Covenant (2022)

Directed by Fiyin Gambo, The Blood Covenant revives Nollywood’s fixation with blood oaths and ritual wealth, updating it for a new generation. It follows three struggling friends whose desperation for success draws them into a secret society built on blood sacrifices.

Unlike the VHS-era classics such as Blood Money or Living in Bondage, this film reframes the theme through contemporary struggles: unemployment, class inequality, and the obsession with quick wealth in a society that glorifies material success.

Polished visuals and suspense-driven storytelling place the film firmly in New Nollywood’s modern aesthetic, but its core lesson is familiar: wealth gained through dark bargains always comes at a deadly cost. In blending old juju cinema tropes with present-day anxieties, The Blood Covenant shows how Nollywood continues to use spirituality and tradition to interrogate the price of ambition.

Elesin Oba: The King’s Horseman (2022)

Based on Wole Soyinka’s classic play, Elesin Oba adapts a historical incident from colonial Nigeria, where tradition and imperial power collided with tragic consequences. The story follows Elesin, the King’s Horseman, whose duty after the king’s death is to perform ritual suicide to accompany his ruler into the afterlife.

His hesitation, compounded by the intervention of British colonial officers who misunderstand the ritual as “barbaric”, disrupts the cycle of honour and duty that holds his society together.

Directed by Biyi Bandele, the film brings Soyinka’s philosophical exploration of fate, duty, and cultural identity to Nollywood’s screen, with lavish costumes, and rich Yoruba dialogue. While staying faithful to its theatrical roots, it highlights timeless questions: What happens when sacred traditions clash with external forces of modernity? And how much of a culture is lost when its rituals are interrupted?

King of Thieves (Agesinkole) (2022)

King of Thieves (Agesinkole) is a Yoruba epic that reintroduces Nollywood to the grandeur of indigenous folklore. The film tells the story of Agesinkole, a dreaded bandit wielding mystical powers who terrorises the prosperous kingdom of Ajeromi. His reign of chaos tests the limits of traditional authority as warriors, hunters, and priests join forces in a desperate bid to protect their people.

Directed by Tope Adebayo and Adebayo Tijani, the film blends large-scale action with Yoruba cosmology, showcasing spiritual warfare, incantations, and traditional justice systems. Its elaborate costumes, special effects, and gripping battles marked a return to the kind of epic Nollywood once shied away from in favour of urban dramas.

Beyond its box office success, King of Thieves sparked renewed enthusiasm for indigenous epics, proving that stories rooted in culture and spirituality can still command massive audiences in contemporary Nollywood.

Aníkúlápó (2022)

Kunle Afolayan’s Aníkúlápó, one of Nollywood’s biggest Netflix hits, dives deep into Yoruba mythology to tell a story of love, betrayal, and the limits of power. It follows Saro, a wandering cloth weaver who falls in love with a queen and, after a tragic death, is revived by the mythical Akala bird. Gifted with the power to raise the dead, Saro quickly transforms from a humble outsider into a man revered and feared, only to be undone by his own greed and betrayal.

Aníkúlápóʼs Netflix success brought epic storytelling back to the centre of Nollywood, proving that films rooted in African spirituality and traditional cosmologies could resonate globally while also sparking debates about morality, fate, and the dangers of unchecked ambition.

Ile Owo (2022)

Directed by Dare Olaitan, Ile Owo is a blend of romance and supernatural horror that places Nollywood’s longstanding fascination with occult power in a modern setting. The film follows Busola, a young woman eager to find love, who falls for Tunji, a wealthy and charming man from an influential family.

Just as her dream romance begins to unfold, she discovers that her suitor’s fortune and family legacy are tied to sinister spiritual practices that demand terrifying sacrifices.

Stylishly shot and dripping with suspense, Ile Owo pushes Nollywood horror beyond campy effects, leaning instead on psychological tension, eerie atmospheres, and shocking reveals.

It reflects a new wave of Nigerian horror that retains the occult obsessions of the VHS era while speaking to contemporary anxieties about marriage, power, and what people are willing to sacrifice for wealth and influence. In updating juju cinema for today’s audiences, Ile Owo shows that Nollywood horror is evolving without losing touch with its spiritual roots.

Breath of Life (2023)

Bodunrin “B.B.” Sasoreʼs multiple award-winning film, Breath of Life is a poignant exploration of faith, grief, and redemption. The film follows Timi, a former clergyman who, after the tragic loss of his wife and daughter, descends into isolation and despair.

His life takes a transformative turn when Elijah, a humble young man with aspirations to start a church, enters his employ. Through their evolving relationship, Timi begins to confront his past and rediscover his purpose.

While the film doesn’t delve into overt supernatural elements, it heavily reflects on the spiritual journey of healing and the presence of the divine in everyday life. The story underscores themes of forgiveness, inner peace, and the enduring power of faith, offering a contemplative look at the human spirit’s resilience.

Mami Wata (2023)

C.J. Obasi’s Mami Wata is a visually stunning reimagining of the legendary West African water spirit, set in the remote coastal village of Iyi. The community venerates Mama Efe, a spiritual intermediary for the goddess, but when outsiders challenge her authority and modern pressures unsettle tradition, the villagers begin to question their faith. The tension between belief and change sets the stage for a struggle over identity, power, and survival.

Shot entirely in luminous black-and-white, the film blends Afrofuturist aesthetics with folklore, creating an atmosphere both otherworldly and grounded in African cosmology.

Its striking imagery, rich symbolism, and feminist undertones earned it international acclaim, including the Special Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival. More than just a tale of a water deity, Mami Wata reframes African spirituality for a global audience, affirming its relevance in conversations about modernity, resilience, and the future of indigenous traditions.

Suspicion (2024)

Directed by Tosin Igho, Suspicion is a dark, superhero-esque thriller that blends crime, occult practices, and moral reckoning. The story follows Voke (Stan Nze), a man born into an occult lineage, whose life unravels after the brutal murder of his best friend and the friend’s daughter. Seeking vengeance, he turns to his mother — a practitioner of black magic — and embraces powers that blur the line between justice and destruction.

What sets Suspicion apart is how it frames its protagonist almost like a tragic antihero, wielding supernatural abilities in a world where vengeance and ritual collide.

Instead of treating juju purely as horror, the film leans into action-driven spectacle, suspense, and moral tension, making it feel like Nollywood’s own take on the superhero origin story. In doing so, it extends Nollywood’s long tradition of ritual cinema into a more modern, genre-blending form.

Ms. Kanyin (2025)

Jerry Ossaiʼs Ms. Kanyin is a supernatural horror film that reimagines the classic Nigerian urban legend of Madam Koi-Koi. The story follows Amara (Temi Otedola), a final-year student at an elite boarding school in Offa, Kwara State.

In a desperate bid to improve her French grade and secure admission to Harvard, she and her friends attempt to steal the WAEC exam papers. Their plan goes horribly wrong, resulting in the death of their French teacher, Ms. Kanyin (Michelle Dede), who returns as a vengeful spirit to punish the students.

The film blends horror, suspense, and folklore to explore themes of spiritual justice, moral reckoning, and the consequences of violating societal and supernatural codes. By turning a modern academic setting into a stage for traditional myth and spiritual retribution, Ms. Kanyin continues Nollywood’s long-standing tradition of using indigenous beliefs to interrogate human behavior and morality.

My Father’s Shadow (2025)

The first-ever Nigerian film to be selected for the Cannes Film Festival and winner of Special Mention for the Caméra d’Or, Akinola Davies Jr.ʼs My Father’s Shadow is a subtle but powerful drama that explores family, memory, and the spiritual threads that connect the living and the dead. The story follows two young brothers spending a transformative day with their estranged father, Folarin (Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù), as they navigate 1993 Lagos and uncover the complexities of his life.

Drawing on African beliefs around presence, legacy, and ancestral guidance, the story hints at moments where the boundary between life and death blurs—echoing familiar cultural stories of deceased loved ones appearing in dreams or visions.

While never overtly supernatural, these sequences underscore the film’s meditation on presence, absence, and spiritual continuity, making it a quietly profound addition to Nollywood’s exploration of tradition and spirituality.

Honourable Mentions

- Secret Gold Mine (1998)

- Oracle (1998)

- Last Burial (2000)

- Issakaba (2001)

- Agogo Eewo (2002)

- Egg of Life (2003)

- Ori (2004)

- Irapada (2006)

- Jagun Jagun (2023)

- House of Ga’a (2024)

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big