I have always believed that authors make great entertainers, too, and deserve celebrity status” — Alexander Nderitu.

By Frank Njugi

For all of Africa’s storied intimacy with the written word, our presence in the architecture of global literature is still young, almost embryonic, if measured against the long, varnished corridors of English letters. What the West has applauded has often been what it could translate, which is mostly pain packaged in postcolonial syntax (think of the late Ngũgĩ wa thiong’o) or suffering rendered legible through the grammar of exile (think of Gbenga Adesina).

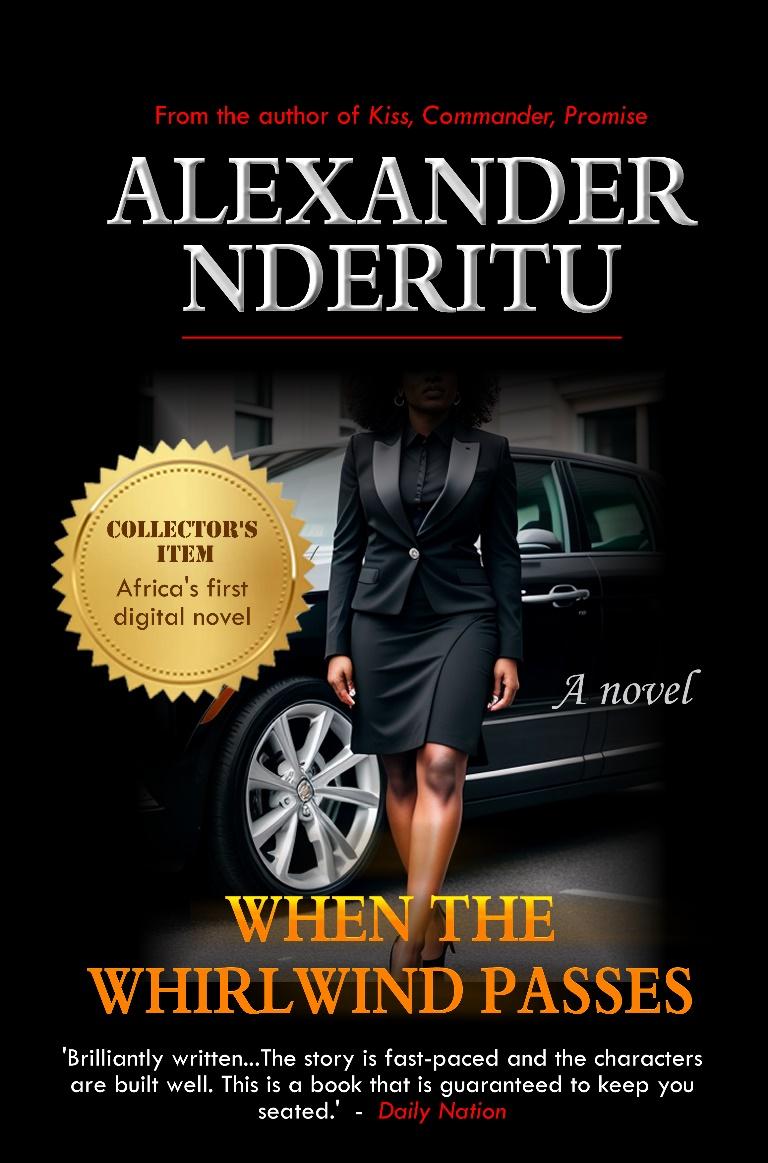

Yet, even within this imbalance, we have always had our own insurgents, writers who refused to wait for permission or precedent. Among them stands Alexander Nderitu, Africa’s first digital novelist, a pioneer who first coded his rebellion in pixels rather than print, proving that innovation, too, can be a form of literature.

Twenty-four years ago, the Kenyan writer quietly made history by becoming the first writer of African descent to publish a digital novel. Since then, he has built a career that feels like a long, patient rebuttal to anyone who ever doubted that Africans could contribute something enduring to the world’s literary imagination.

In 2004, his tragic spy story, Life as a Flower, earned him a nomination for the Douglas Coupland Short Story Award. Three years later, his comedic stage play, Hannah and the Angel, won The Theatre Company’s top prize. By 2017, Business Daily had named him one of Kenya’s Top 40 Under 40 Men, and in 2020, he was a finalist for the Collins Elesiro Literary Prize.

More recently, Nderitu’s trajectory has expanded beyond the page into something grander and ambassadorial. He was appointed Director of the Nairobi Chapter of the Asian Literary Festival, a Silk Road–formatted gathering set to unfold in Nairobi over the next five years, uniting African and Asian literary voices. Maybe the most fitting role for a writer who has always embodied literature as not a static inheritance but a living exchange.

Nderitu is also the founder of The Alexander Nderitu Prize for World Literature and the literary magazine, The African Griot Review, ventures that speak to a faith in the future of African letters and his desire to build an ecosystem rather than just a legacy. In this exclusive interview with Afrocritik, Nderitu opens up about his evolving literary journey, from writing and curation to publishing, and the deeper question of what it means for his people to take their rightful place within the world’s literati.

You have been writing —and publishing— in multiple forms for more than two decades, from your landmark debut as Africa’s first digital novelist to your recent work as a cultural organiser. Over the years, have your aspirations or creative goals changed significantly? If you were to describe your writing today versus ten years ago, what shifts would stand out most clearly to you?

The overall goal hasn’t changed. I was an avid reader as a child, and I dreamt of being a famous writer someday, a goal I’m still pursuing. I love to write. Over the last twenty years, I have written in just about every genre. There are some aspects of the writing business that I wasn’t aware of when I started out, such as speaking engagements, festivals, book fairs, and book clubs.

Over the last ten years, the main change in my writing is perhaps that I started doing non-fiction and literary criticism. Initially, all I did was fiction, poetry, and the occasional stage play. Of late, I have ventured into publishing, creative writing workshops and, most recently, event organisation.

As for the business itself, one of the most significant changes is the role of the Internet and Social Media. We now have literary groups on such apps as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Telegram. We have YouTube channels, aka Booktubes. We have TikTok, X, and Instagram hashtags that unite readers worldwide under certain topics. Podcasts and AI are probably the latest rage. As a matter of fact, I was excitedly listening to an AI-generated podcast of my essay, “The Cartography of Human Behaviour”, on Academia.edu just the other day.

In 2002, you became Africa’s first digital novelist by publishing When the Whirlwind Passes online. What was that experience like in terms of reception, infrastructure, and challenges at such an early period? And looking back, how do you assess the impact of that move (digital publishing) on your career and on African literary culture at that time?

It actually came out in 2001, but was first reviewed in 2002. E-books were very experimental at the time. Social Media apps did not exist. One of the first sites I uploaded it to was EbookMall.com. The first time I sold a copy, I received a check for USD$1.50 in the mail.

The banking fees for processing it would have been more than that amount. I still have it. Along the way, more options opened up, most famously the Amazon Kindle. Print-on-Demand also became a reality.

I particularly loved a site called Lulu.com. Along the way, a not-for-profit organisation designed to distribute e-books was founded by David Risher and Colin McElwee in the USA and Spain. It was called Worldreader. I was one of the first independent publishers to be onboarded. Their mobile phone app shared books worldwide in multiple languages and gave valuable feedback to the publishers. The kind of information that can’t be gathered manually. I had several titles on the app and they were read by tens of thousands of people globally.

Being a digital writing pioneer made an instant attraction in the literary scene. I was invited to do interviews, university talks, workshops and festivals. I was the first author to appear on the cover of Zuqka (now MyNetwork) magazine. That was significant because Zuqka and Pulse were the go-to mags covering the entertainment scene, and they mostly featured musicians and actors. I have always believed that authors make great entertainers, too, and deserve celebrity status.

You are known for interests in fashion design, music production, and film. How do these creative domains inform or intersect with your writing? Of all the art forms you engage with, which feels closest to your ‘core’ creative self, and why?

Like most artists, I am actually interested in various art forms. Unfortunately, one rarely has time to indulge in multiple pursuits these days. But you can see my other interests in my writings. When the Whirlwind Passes, a crime novel, revolves around a fashion house and was inspired by a real one.

Music permeates both my non-fiction and fiction works; stories like Empress from Asmara and The Music Stays the Same. I am a man of many interests. Of course, long-form fiction is what is closest to my heart. I am a storyteller. Poetry is also very dear to me. My fourth solo book of poetry is to be published in Italy this year. The previous ones were The Moon is Made of Green Cheese, King Bure is Dead! and Where the Kremlin Live.

You once published a paper titled Changing Kenya’s Literary Landscape, arguing Nairobi was ripe to be a UNESCO City of Literature. What concrete changes would you say have happened in Nairobi’s literary ecosystem since then, and what remains to be done? What would Nairobi need (in your view) to fully merit or secure UNESCO City of Literature designation?

I first heard about UNESCO’s City of Literature programme at an Arterial Network event in Nairobi many years ago. I left feeling that Nairobi deserved that status and I talked to a few fellow writers about possibly pushing for it. Of course, the actual submission for consideration would have to be made by the Nairobi County Government, probably the Department of Culture.

Since Devolution in 2013, Kenya no longer has town mayors. In my paper, Changing Kenya’s Literary Landscape, I used my own experiences and observations to support my claim that Nairobi is a ‘city where literature thrives’. There were ‘inama bookshops’ (street booksellers) on pavements, regular book readings and poetry performances, numerous book launches, experimental literature, digital literature (which I pioneered), international festivals like StoryMoja, book fairs like Nairobi International Book Fair, book salons, literary journals like Kwani?, literary supplements in the newspapers, a healthy library-to-population ratio and, of course, an impressive number of scribes.

Kenyan writers have garnered quite a number of international literary awards, such as the Caine Prize and Commonwealth Prize. COVID-19 slammed the brakes on events, but even then, the literary community remained active on social media. Now, the events are back and we even have new festivals like Macondo and the Kenya International Theatre Festival. We also have new home-grown literary contests and award schemes. The excitement is back.

The stated aim of UNESCO’s City of Literature programme is ‘to promote the social, economic and cultural development of cities in both the developed and the developing world.’ To be approved as a City of Literature, cities need to meet several criteria, one of which is ‘hosting literary events and festivals which promote domestic and foreign literature.’

The fact that Nairobi was the first African city chosen to host a franchise of the Asian Literary Festival is further evidence of its importance in the literary landscape. Currently, only two African locations have UNESCO City of Literature status: Buffalo City and Durban, both in South Africa. I believe Nairobi belongs on that list, and so do a few other African cities, such as Cairo, Lagos, and Marrakesh. But a city has to be proactive in seeking any type of international status or recognition. You can’t win a contest that you never entered.

The prize you founded, The Alexander Nderitu Prize for World Literature, which has already moved from short stories to one-act plays, and your magazine, The African Griot Review, both suggest an evolving vision for how African literature engages with the world. What do these platforms reveal about your understanding of where African writing is today, and where you believe it needs to go?

The Prize is open to people from all corners of the globe, hence the ‘world literature’ suffix, and is intended to identify and promote literary talent. It rewards unpublished literary works in the various genres that the founder writes in. Last year it was short stories, this year it’s stage plays.

Next year, it will be either novel manuscripts or poetry. I think this international prize signals the rising confidence of the Global Majority. In the past, major ‘African’ awards were either founded or funded from abroad. I have always had a problem with that paradigm. For instance, when there’s an international sports tournament such as the World Cup, the Olympics, or Davis Cup, each country identifies its best athletes and sends them to represent it.

Why our cultural heroes – such as musicians, actors, and writers – are crowned abroad has always been a mystery to me. I have said this so many times: we need to identify our own heroes and then present them to the world.

The African Griot Review, an avant-garde arts-and-culture magazine, is one of the pillars of The Alexander Nderitu Prize. ‘Griots’ (pronounced gree-o-s) were ancient African historians, storytellers, and singers. Think of a person who acts as the village library – that’s a griot! A very important source of information.

As to where African lit is today, I’d say it has come a long way, and it can only get bigger. We have more lit mags, festivals, book stores, awards, and authors than ever before. The ecosystem is becoming ever more robust. I want to see our literature gain international traction, the way South Korean K-dramas and K-pop music are currently doing.

Running a prize and a magazine often demands as much diplomacy and infrastructure as creativity. From securing fair submissions to nurturing new voices, there’s always tension between idealism and logistics. What challenges have you encountered in sustaining these initiatives, and how do you reconcile the role of editor-organiser with your own work as a writer

Yes, a lot of diplomacy goes into these international collaborations. For example, for the 2024 Alexander Nderitu Prize, the judges hailed from Sweden, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, Botswana, and Kenya.

I have also been a juror of the Asian Prize for Short Stories. It helps to establish and maintain warm relationships with other literati, wherever they may be. When it comes to award schemes, the two biggest challenges are fundraising and establishing credibility. The other parts are administrative and time-consuming but not really difficult.

The themes, judging criteria, terms, and conditions are established beforehand. This forestalls a lot of later disputes. It’s up to the aspiring participants to decide whether a certain contest or award scheme is for them or not. The rules are rigid and entries are read ‘blindly’ so the chances of bias are very low.

What I’d like to stress is that the cash prize (where available) should never be the motivation. The achievement or honour of being an award-winner is the real goal. And that goes for all awards across the board. Some of the most prestigious awards – like Oscars and Grammys – don’t have cash prizes at all. But win one and it will be forever attached to your name, even after your transition from this dimension of space-time! Prestige lasts longer than money.

There are many challenges in judging awards, especially if you’re the administrator. Getting the right judges is a challenge. Previous award winners in that genre are the most sought-after jurors. Publicizing the contest so that it reaches a reasonable cross-section of your target demographic is another challenge.

Also, some submitters don’t follow the rules and have to be disqualified. For example, my current call-out is for one-act plays but some people have mailed in multiple-act books. It doesn’t matter how good such a work is because it can’t be allowed to win over the ones that strictly follow the guidelines. But, overall, running an award scheme is a fulfilling experience. I like it.

Recently, you took on the direction of the Nairobi chapter of the Asian Literary Festival. With a five-year license, how do you envision the festival evolving over time? What is your ‘North Star’ for it?

If everything goes according to plan, within three years, the Nairobi Edition of the Asian Literary Festival will be the biggest lit fest in Africa. It will be like one big, fat, multicultural wedding that people will look up to year on year.

The ALF is rooted in Asia. How do you plan to balance Asian literary voices with Kenyan, African, and global voices in programming? And what do you see as the greatest mutual benefits in bringing Asian literary voices to Africa and vice versa?

ALF is a platform, just like Facebook, YouTube, or TikTok are platforms you can use to better yourself or spread a message. The Nairobi version will host about one hundred authors, about seventy of them from the continent. They will be involved in discussions, workshops, paper presentations, book signings, art exhibitions, and other engagements. One of the most exciting aspects of festivals is seeing authors from different countries in conversations.

The Nairobi ALF is seven months away, and already prominent authors from nations like Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, and Tanzania have expressed interest in participating. They know how illuminating and enjoyable these international meets can be. And for authors, publishers, or other artists who will not be on the programme but would want to utilise such a prestigious platform to launch or exhibit books, present an award, or advertise something, there’s room for that. They just need to get in touch with the organisers. By the way, the winner of the 2025 Alexander Nderitu Prize for World Literature will be announced at the ALF next year.

Relations between Asia and Africa are nothing new. East Africa, the Gulf States, and Southern Asia are ‘monsoon cousins’. Travel and trade between Asia and Africa have been going on for centuries. The most obvious consequence is our Kiswahili language, which came about as a result of interactions between the Coastal Bantu people of Eastern Africa and seafaring Arabs.

Kiswahili also contains loan words from India and Portugal. And yet Kiswahili is the most famous African tongue, one of the ‘official languages’ of the African Union. You can also see the Arabian influence at the Coast in the culture, architecture, music, and even genetics of Coastarians.

Relics of ancient Arabic, Asia,n and European interaction are strewn from the Swahili Coast all the way inland to Southern Africa, and are now tourist attractions. Kenya is also home to a sizable population of citizens of South Asian heritage. We’re just celebrating them, in a digital age. Maybe the theme of the 2026 ALF should be ‘Digital Monsoon’ or ‘Navigating the Sea of Ideas’ or ‘Ancient Connections, New Dimensions’.

Some critics argue that foreign literary festivals or ‘imported’ ones risk overshadowing local initiatives or privileging international tastes. How do you respond to such critiques?

I prefer to think of the ALF as a culture-sharing event. It’s not just about books and authors. There will be music, films, food, and fashion items from different cultures. For example, foreigners will be able to see and buy Maasai accessories, watch Kiswahili documentaries, enjoy local cuisines, and listen to discussions on books by African and Asian cultural treasures – there are national parks, animal orphanages, museums, MICE facilities, world-class restaurants, international restaurants, casinos, airports, safari guides, world-class hotels – you name it. I want ALF to be added to the calendars of local tourism and aviation magazines and websites.

Amid these administrative and leadership responsibilities, how do you maintain your own creative writing practice? What projects are you currently writing or planning? Do you find tension between institutional/organising work and creative work? How do you balance them?

As you might expect, sacrifices have to be made here and there. My personal writing has taken a back seat because I have so many other responsibilities. I haven’t released a single book this year, apart from the one that will be published in Italy. I still write but only in short bursts.

As always, I work on different projects simultaneously. I have stage plays waiting to be performed. I am working on a volume of poetry in my native Gikũyũ language. I have a collection of spy stories that is almost complete. My third book on theatre should be complete by the end of December. I might start a podcast, like everyone else! I write whenever I can.

In conclusion, what advice would you give a young Kenyan and African writer who wants to engage more internationally?

Get a literary agent. Without one, ‘going international’ is very difficult, unless you win a major prize or something like that. Unfortunately, there are not many agencies inside Africa. However, there are lots of international agents actively looking for clients, and their contacts and areas of interest are available online.

The most popular publishers in the world are inundated with manuscripts. For that reason (and to avoid legal issues), many of them no longer deal with authors directly. Agents act as a screening service. Top agents fly around the world to attend major book fairs. These are the main marketplaces for selling and buying book rights.

This saves the scribe a lot of time and money, not to mention that even if the author visited book fairs, unless he’s an agent as well, he might not be allowed to trade rights. If you look at the top African authors, including the ones in the diaspora, you will notice that the vast majority are represented by agents.

Frank Njugi, an award-winning Kenyan Writer, Culture journalist, and Critic, has written on the East African and African culture scene for platforms such as Debunk Media, Republic Journal, Sinema Focus, Culture Africa, Drummr Africa, The Elephant, Wakilisha Africa, The Moveee, Africa in Dialogue, Afrocritik, and others.