Should filmmakers be bound by the constraints of censorship, or should they be free to tell their stories in full, without fear of retribution?

By Felicitas Offorjamah

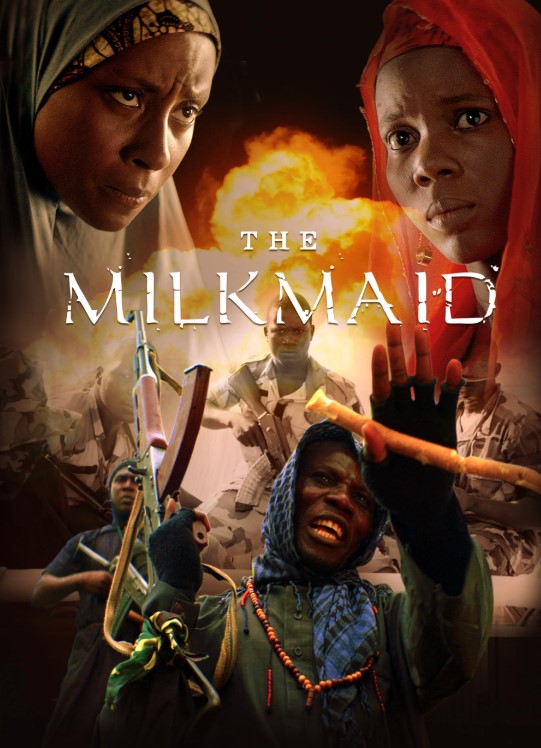

In the closing scenes of The Milkmaid (2020), a young woman walks through a landscape scorched by the trauma of terrorism, her body and spirit marked by what she has survived. The film, directed by Desmond Ovbiagele, is a haunting portrayal of life amid Nigeria’s insurgency. But its journey to the screen was fraught with obstacles. Despite being Nigeria’s official submission for the Oscars, The Milkmaid was mutilated by Nigeria’s National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB), which demanded the removal of scenes referencing Boko Haram and Islamic extremism. The version that premiered in Nigerian cinemas was a sanitized shadow of Ovbiagele’s original vision.

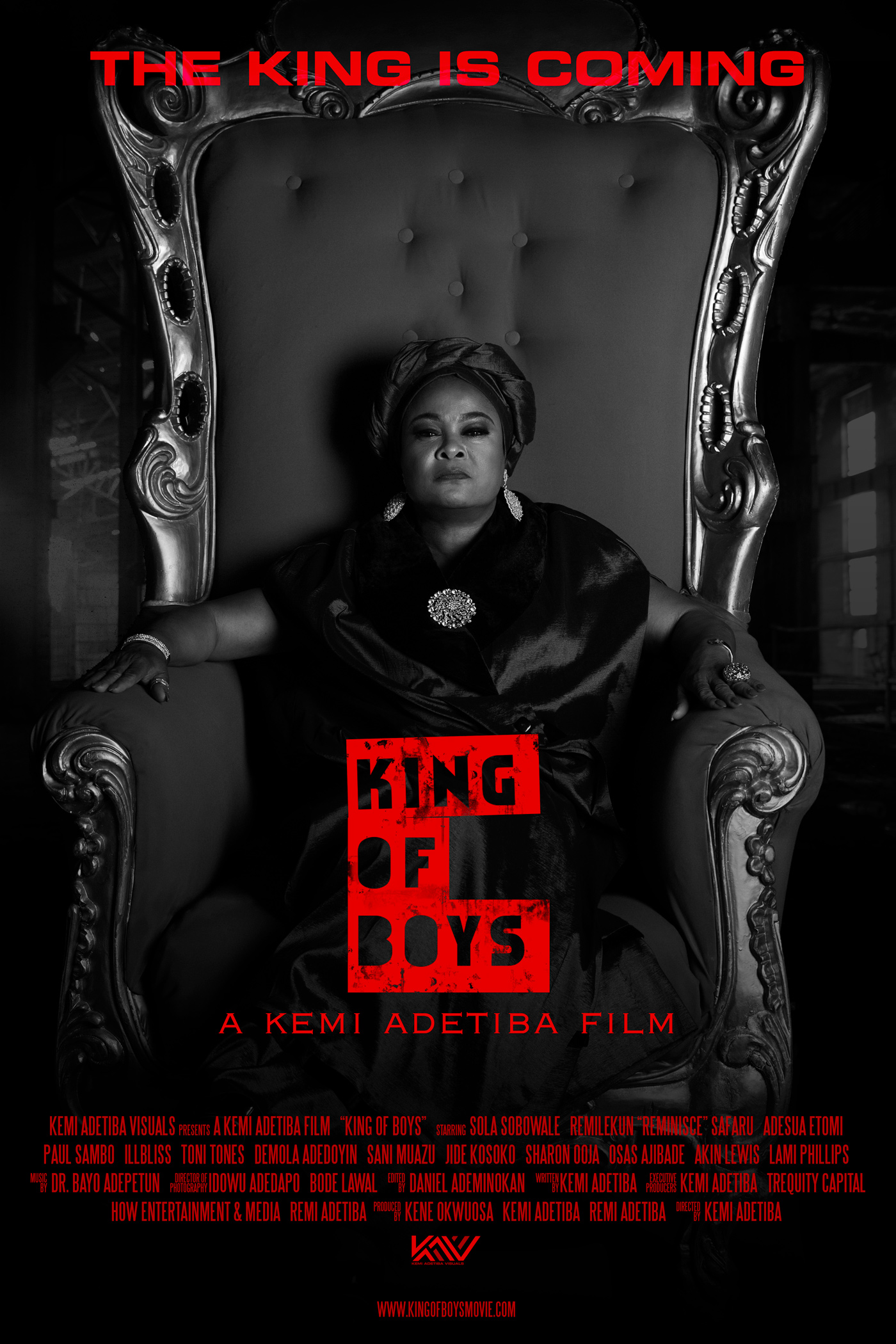

This story is not unique. In recent years, Nigerian filmmakers have begun to tackle the political, social, and cultural crises of the nation with bold cinematic language. Films like Òlòtūré (2019), King of Boys (2018), and Gangs of Lagos (2023) have moved past melodrama into the terrain of social critique. But their rise has coincided with intensifying censorship, raising difficult questions about artistic freedom in a democracy struggling with its own reflection.

The NFVCB posits in its mission statement that it aims “to contribute to the positive transformation of the Nigerian society through the censorship of films and video works whilst balancing the need to preserve freedom of expression within the law, and limit social harm caused by films.”

Some industry participants agree with the mission, but they are sceptical that its approach to topics such as government corruption, insurgency, or police brutality needs to be addressed, as they often face roadblocks. Òlòtūré, for example, was released on Netflix rather than in Nigerian cinemas, reportedly to avoid regulatory hurdles. The move paid off internationally, but within Nigeria, it sparked a heated debate on whether streaming platforms offer a loophole or a means of self-exile for bold storytelling.

Nollywood, Nigeria’s rapidly evolving film industry, has long been known for its colorful dramas, escapist comedies, and vibrant storytelling, and films in the industry have traditionally avoided explicitly confronting sensitive political issues.

Wilfred Okiche, a Nigerian film critic and cultural commentator, states that the tension isn’t just about overt censorship—it’s about the pervasive atmosphere of fear that prompts ‘self-censorship’ before a script is even written. “Even before the filmmaker starts, he’s not allowed to be ambitious, to go as daring and provocative as his imagination could allow,” he said. “From the moment they dream of a story, they are already punishing themselves, editing their creativity for fear of what the board might do.”

Yet Okiche is quick to stress that political storytelling isn’t new in Nollywood. He recalls early filmmakers like Teco Benson and Lancelot Oduwa Imasuen, who tackled national issues head-on. What’s changed, he argues, is the visibility and ambition of recent political films, which now command global attention. “King of Boys was a landmark. It proved political films can be commercially successful and globally relevant”.

He emphasises that the context in which these films are created—reflecting Nigeria’s social, political, and cultural landscape—remains deeply ingrained in the storytelling process. Okiche adds that films cannot exist in isolation from the realities of their environment: “Film industries don’t exist outside of the context of the countries in which they were born. The political context, the social context, the cultural context—these cannot be divorced from Nollywood”.

Films such as King of Boys, which tells the story of a powerful and ruthless woman navigating political and criminal landscapes, have sparked conversations not only for their gripping narratives but also for their portrayal of the corrupt, power-hungry elites who dominate the Nigerian political scene.

Òlòtūré, another film in the same vein, deals with the grim realities of human trafficking in Nigeria, unmasking the dark underbelly of exploitation, corruption, and the abuse of power. These films are providing an unflinching look at the realities of Nigerian society, shedding light on social issues that are often hidden from mainstream media.

But tackling these subjects head-on has proven difficult, given Nigeria’s restrictive censorship regulations. Some filmmakers complained that it limits their artistic expression and hampers the products of their imagination.

As Desmond Ovbiagele, director of The Milkmaid, explains, censorship in Nigeria forces filmmakers to navigate a complex system where artistic vision often clashes with governmental concerns over national security and political sensitivity. The Milkmaid tells the harrowing story of a young woman caught in the middle of religious extremism, a subject that strikes at the heart of Nigeria’s ongoing battle with terrorism and insurgency.

However, Ovbiagele’s film faced considerable scrutiny from the Nigerian Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB), which demanded that certain scenes be edited or removed, citing their sensitivity in light of the political context.

The director, who had gone through the usual process of submitting the completed film to the censor board to take a look at and to receive a classification, said that the agency had reverted back with some comments in terms of certain scenes in the film, which they felt were sensitive and needed to be amended.

“We went to some length to explain the rationale and the logic behind those scenes in the film and to explain the instrumentality to the narrative of the film. We eventually went back and forth at length with them in the bid to try to arrive at a solution that assuaged some of their concerns without unduly compromising the vision for the film. That took a while, but eventually we arrived at a cut of the film. That they were finally willing to give a classification but that process was a fairly extended process before we got to that point.”

Censorship in Nigerian cinema is a constant challenge for filmmakers, particularly those dealing with politically sensitive subjects. The NFVCB’s role is to ensure that films meet certain standards of decency and safety for public consumption, but this oversight often crosses into the realm of creative restriction.

While Ovbiagele, for instance, successfully defended the integrity of many scenes in The Milkmaid, the censorship process ultimately forced him to cut certain portions of the film, altering the final product from its original conception.

Ikong Esseiet, who identified herself as a die-hard lover of The Milkmaid movie, said that, “When I saw the movie, I was awed and just knew that the initiator wanted to “do more” but his hands were tied in a loose but tight rope.”

Okiche’s critique of the NFVCB highlights the broader implications of censorship on Nigerian filmmakers. He argues that the very existence of a “censor board” sets a problematic precedent by instilling self-censorship in filmmakers. “What it does is it makes filmmakers censor themselves even before they begin to dream about their stories,” Okiche notes.

This is particularly problematic for political films, which often confront issues that are uncomfortable for the powers that be. The fear of backlash or financial repercussions for tackling politically sensitive subjects leads many filmmakers to second-guess their creative choices, self-editing before even reaching the censors. It’s always bad, not positive. That agency, if not scrapped, should be reorganized for a more fruitful purpose.”

This issue is exemplified in the case of Half of a Yellow Sun (2013), which was another high-profile example of censorship’s reach. Based on Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel, the film was delayed due to its politically charged portrayal of Nigeria during the civil war. On this backdrop, beyond censorship, financial blacklisting is another growing concern. “Investors are wary of funding politically sensitive projects,” says a director who requested anonymity. “If your film is seen as too controversial, your funding can disappear overnight.”

Okiche added that people do not want to invest in films that would run into trouble along the line. “Like the people who invested in Half of a Yellow Sun, they found out the hard way not investing in films that are politically sensitive or historically sensitive.”

Whispers from citizens also reveal that if the “government man” decides that he does not like the direction of your film or the criticism, it could brew trouble. The film critic further explained that, “beyond using the censor board as a legitimate way to get back to you. They can find a way to make your life difficult by making it difficult for people to see these films. I abhor censorship. It’s a slippery slope. Freedom of creativity, freedom of expression is what I always preach”.

Some filmmakers opt for strategic compromises. Scenes are rewritten, dialogues toned down, and narratives adjusted to slip through the cracks of censorship. Others take a more defiant stance, embracing underground screenings, international film festivals, and direct-to-consumer distribution via social media.

“There’s a tension I have with censorship”, says Okiche. “Even just the title of the board, that ‘censor’ in it—Censor rings an alarm in my head. Why do you need to censor stuff? I’m not a believer in censorship in any form. We should have freedom of artistic expression… within the law.” He further critiques the situation, suggesting that the censor board doesn’t just regulate content but enforces a climate of self-censorship in filmmakers that undermines their ability to create freely.

The films discussed here are not merely works of fiction; they are also reflective of the real-world political and social issues Nigeria faces. The Milkmaid stands as a stark portrayal of religious extremism, with Ovbiagele using his narrative to illustrate the devastating impact of insurgency on ordinary people.

In his interview, Ovbiagele describes how the inspiration for the film stemmed from his observations of the Boko Haram insurgency and the broader issue of extremism in Nigeria. The film seeks to illuminate the personal toll of extremism, telling the story of a young woman who is caught in the crossfire of an unrelenting conflict that has ravaged Nigeria for years.

“The film is a reflection of a personal journey I’ve had watching insurgency unfold and watching its effect on people, especially women,” he says. “The idea of using cinema to speak about extremism felt necessary. I felt that as filmmakers, given the influential tools we had at our disposal, we have an obligation to tell these sorts of stories, especially as the issue has affected a vast swath of the country and could expand.” Ovbiagele’s film speaks directly to the increasing instability in Nigeria, offering a humanising view of a conflict that is often discussed only in abstract, political terms.

Similarly, Òlòtūré explores the intersection of corruption, power, and exploitation, tackling the issue of human trafficking in Nigeria. The film’s raw and unflinching portrayal of the horrors women face at the hands of traffickers is a stark commentary on the failure of state institutions to protect their citizens.

Directed by Kenneth Gyang, the film dives into the world of human trafficking networks, showing how vulnerable young women are manipulated and exploited for profit. Like The Milkmaid, Òlòtūré does not shy away from portraying the grim realities of political and economic corruption, making it an important contribution to Nigeria’s ongoing discourse on social issues.

In Okiche’s view, the rise of films like King of Boys is emblematic of a larger shift in Nollywood. “The success of King of Boys is a landmark,” he says. “It’s more global than local, and I hope it continues that way.” Okiche points out that these films open up discussions of corruption and political manipulation in ways that feel fresh and engaging, all while offering Nigerian audiences films that are both commercially successful and politically engaging.

At the heart of these films is a fundamental question about the role of the artist in society. Should filmmakers be bound by the constraints of censorship, or should they be free to tell their stories in full, without fear of retribution?

Ovbiagele’s experience with The Milkmaid demonstrates the challenges of navigating a creative vision while adhering to government regulations. Despite these constraints, he maintains that the story of The Milkmaid needed to be told in its original form, arguing that the film’s exploration of extremism was necessary for a wider understanding of Nigeria’s current political struggles.

“The function of censorship anywhere in the world is to apply a certain degree of judgement or assessment to content submitted to it and to ensure that that content from its point of view is fit for public consumption. So, we went through that process as a storyteller, and this applies to any storyteller”.

For The Milkmaid director, stories are developed and conceived through respective and individual inspirations, and are inspired to present those stories to the public. “And whatever inspires us, whatever the scope and breadth of our vision is, and the particular components of our vision may not go well with or resonate with those who are tasked with the responsibility of providing regulatory oversight over what enters the public arena.”

Similarly, Okiche’s critique of the NFVCB highlights the dangers of self-censorship, particularly when it stifles the ability of filmmakers to push boundaries and challenge political and social norms. Okiche is an advocate for freedom of expression, believing that filmmakers should have the freedom to explore difficult subjects without fear of government intervention. This desire for artistic freedom is echoed in the success of films like King of Boys and Òlòtūré, which, despite facing hurdles in terms of censorship and political sensitivity, continue to find audiences eager to engage with these complex, politically charged narratives.

As Nollywood continues to grow in both size and influence, films like The Milkmaid, King of Boys, and Òlòtūré are pushing the boundaries of what is possible in Nigerian cinema by offering powerful commentary on the political, social, and economic issues shaping the nation. However, these films also face significant challenges, particularly in terms of censorship and government control. The censorship of politically sensitive material remains a pervasive issue, forcing filmmakers to carefully navigate the line between artistic freedom and regulatory compliance.

Despite these challenges, the continued success of politically engaged films demonstrates that there is a growing appetite for stories that tackle the pressing issues of our time. Whether through the lens of extremism, corruption, or social justice, Nollywood’s political films are engaging with the cultural zeitgeist in a way that few other art forms can.

As the industry evolves, it will be crucial for filmmakers, critics, and audiences alike to advocate for greater freedom of expression, ensuring that the voices of those who challenge the status quo can continue to be heard.

Felicitas Offorjamah is a creative writer whose work has appeared in The Guardian, Edge of Humanity Magazine, The Lens Magazine, and Nigerian Travels Magazine. She was listed among the top ten winners of the fifth edition of Samson Abanni’s Poetry Contest. Felicitas has served as an editor for university magazines and newspapers. When she’s not writing, she’s singing the songs she’s written. You can find her on Instagram at @feli.is.a.writer.

Cover photo: Still from The Milkmaid