Lights Out is not a perfect film; uneven, overly ambitious, and occasionally meandering, but it is a necessary one.

By Joseph Jonathan

In many African societies, memory is not just an archive of personal experience but a communal currency. To forget is to risk disconnection from ancestry, story, and self. Yet, in Lights Out, Cameroonian filmmaker, Enah Johnscott, dares to hold a mirror to the erosion of that memory, both literally and culturally, through the intimate prism of dementia and institutional caregiving. It is a film that wrestles with tenderness and terror, with the contradictions of modernity where the age-old duty of caring for elders collides with economic realities and emotional fatigue.

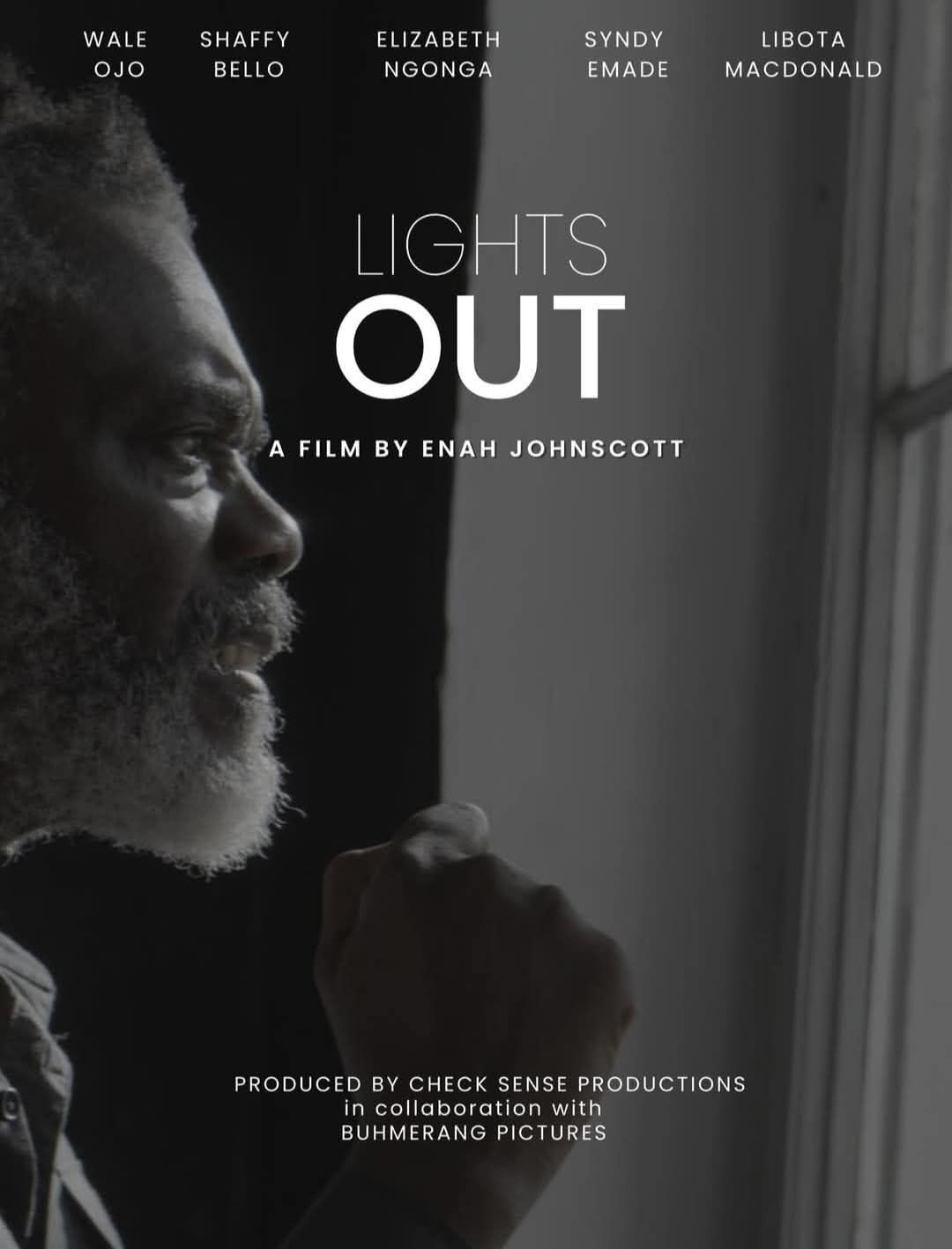

Written by Buh Melvin and starring Wale Ojo, Shaffy Bello, and Ngongang Elizabeth, Lights Out is set in and around the Anone Dementia Care Foundation, a privately run facility facing imminent closure. The film opens with a jarring image: Lucas (Ojo), an elderly man, is shoved into a car in the middle of a chaotic city street.

When he regains consciousness, he finds himself in a tranquil but unfamiliar place, greeted by strangers who insist they are helping him. His confusion is palpable. Are these people his captors or his caretakers? Is this a kidnapping or a rescue mission? From this premise, the film unfolds two parallel threads — Lucas’s psychological unraveling and the institution’s struggle to survive — both slowly collapsing into one another like overlapping dreams.

As Lucas resists the staff’s attempts to diagnose and stabilise him, his paranoia heightens. He believes he has been abducted, that something sinister lurks beneath the surface of this pastoral facility. Yet, beneath his fear lies the ache of an aging man at war with his mind. The arrival of Monica (Ngongang Elizabeth), a childlike new patient who shares his room, introduces an uneasy calm. She becomes his emotional tether, the one person he trusts, their interactions oscillating between companionship and delusion.

Around them orbit Dr. Henry (Libota McDonald) and Maria (Shaffy Bello), the facility’s founders, whose dream of compassionate care is crumbling under financial strain. Their speeches about dignity and responsibility sound noble, but Johnscott cleverly lets the camera linger on their exhaustion — administrators who have become as trapped as their patients.

It soon becomes clear that Lucas’s story is not merely about forgetting, it is about what memory protects us from. Through fragmented flashbacks and glitches reminiscent of corrupted video tapes, we glimpse the trauma that fractured his psyche: a Christmas-time tragedy that left scars too deep to heal. By the time the truth of his past surfaces — a revelation involving family betrayal and long-buried guilt — the film has already made its point: memory is both salvation and curse.

What distinguishes Lights Out is not its mystery, but its moral geography. Western cinema has long explored dementia as metaphor — think The Father (2020) or Amour (2012) — yet Johnscott’s film reframes it within an African moral economy where care is collective. In one of the film’s sharpest subtexts, the act of institutionalising the elderly is portrayed as a foreign import, one that unsettles traditional assumptions of familial obligation.

When Maria pleads for donations to keep the home afloat, her words double as a critique of societies that abandon moral duty to bureaucratic charity. The film confronts the uncomfortable truth that the erosion of memory mirrors the erosion of communal ethics.

Still, Lights Out falters under the weight of its ambition. Its dual narrative — Lucas’s psychological decline and the institution’s collapse — rarely achieves harmony. Scenes feel spliced rather than woven; emotional momentum gives way to exposition. A mid-film monologue by Maria about the sanctity of care feels didactic, explaining what the film has already shown.

Similarly, the final reveal of Lucas’s backstory, though emotionally potent, comes so late it feels less like catharsis and more like an afterthought. Johnscott and Melvin reach for profundity, but sometimes confuse confusion with complexity.

And yet, what saves Lights Out is its sincerity — the emotional intelligence pulsing through its performances. Wale Ojo, in a career-high turn, embodies the tragic dignity of a man slowly erasing himself. His physicality — the trembling hands, the sudden bursts of aggression — conveys more than the script ever could. Shaffy Bello plays Maria with polished restraint, letting small gestures betray a woman unraveling beneath her stoicism. Ngongang Elizabeth delivers an unexpectedly delicate performance as Monica, her innocence amplifying the film’s melancholy.

Visually, the film is arresting. Cinematographer, Takong Delvis Mezzo, frames the Anone facility with lush, deceptive beauty — sun-drenched gardens, echoing hallways, and the haunting stillness of isolation. The use of digital distortion as a metaphor for fading memory is both literal and poetic. The score, at first meditative, eventually overwhelms, yet even that excess mirrors the chaos of fractured cognition.

By its end, Lights Out refuses to offer easy redemption. There are no miraculous recoveries, no sentimental reunions. Instead, it closes on ambiguity; the facility’s fate uncertain, the residents caught in the liminal space between lucidity and loss. Johnscott’s camera lingers not on closure but on care itself, weary yet persistent.

In a year of loud, plot-driven African cinema, Lights Out stands out for its quiet defiance. It is not a perfect film; uneven, overly ambitious, and occasionally meandering, but it is a necessary one. It confronts what we would rather not see: the slow disintegration of memory, and with it, of identity and responsibility. Its cultural weight lies in its insistence that to care — truly care — for those who forget us is to remember who we are.

And perhaps that is Lights Out’s most haunting truth: when memory goes dark, the real question is not what we’ve lost, but who among us will keep the lights on.

Rating: 2.5/5

*Lights Out had its world premiere at the Silicon Valley African Film Festival (SVAFF) 2025 before making a stop at the Abuja International Film Festival (AIFF) 2025.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big.