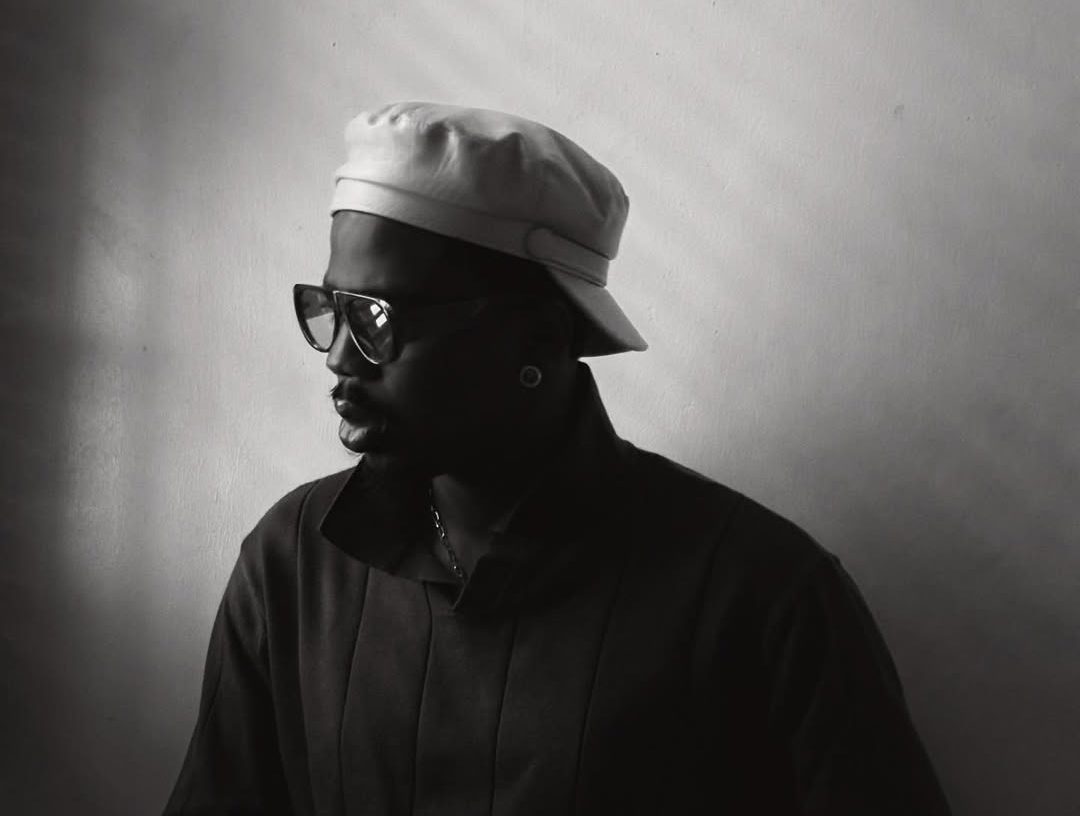

“So even years from now, I want people to watch my videos and still feel something, still connect with the emotion and the message. If the story holds them, if it makes them remember a feeling, then I’ve done my job”. — Perliks

By Abioye Damilare Samson

Abdulrasaq Adebayo Babalola (Perliks) didn’t want to be in Mushin that day. A few months out of secondary school, with dreams of becoming a footballer, he found himself dropped off by his father at a production house. When he saw his new boss, covered in tattoos, in a neighbourhood with a reputation for toughness and street culture, he thought it was punishment. “Based on what I knew about Mushin, I thought my dad brought me there to punish me”, Perliks recalls, laughing at the memory now. “But the man was calm. He told me my dad had dropped me off to learn”.

What followed was reluctant acceptance. “I didn’t like it at first. It felt stressful because, to be honest, I’m a bit lazy”, he admits. But his boss said something that would change everything: “Give yourself time to learn this. You will enjoy it”. He was right. That short but transformative statement unlocked something in him.

Before I knew Perliks as a music director, I first encountered his work in 2021 through his Plastic Angel project, an environmental art initiative in which he gathered, washed, and sorted more than 5,000 pieces of plastic with over 100 volunteers and transformed them into angel wings and public murals. It was a bold visual statement on plastic pollution, and proof that this is someone whose creativity refuses to be boxed in.

Today, Perliks has directed music videos for some of Nigeria’s heavyweight artistes — Burna Boy, Rema, Kizz Daniel, Young Jonn, Adekunle Gold, Joeboy, Seyi Vibez, and more — crafting visuals that have shaped how millions worldwide experience Afrobeats. Yet, his approach remains almost counterintuitive in an industry obsessed with directorial signatures and viral moments: he insists that music videos are “95% about the artiste and only 5% about the director”.

It is a philosophy born from understanding legacy, fighting for independence, and learning that the best stories are the ones you tell for others, not yourself.

The Weight of a Name

Perliks is the son of Tajudeen Babalola Ojora, known professionally as Telemoon, the veteran music video director who was instrumental in the Fuji music ecosystem. Telemoon directed videos for Fuji legends such as Wasiu Ayinde (K1), Pasuma, Malaika, Obesere, Saheed Osupa, and more. According to Perliks, his father’s influence ran so deep. But when Perliks began his journey at that Mushin production house, editing Fuji videos and live performances of the same legends his father had worked with, he made a conscious decision not to trade on his father’s name. “My colleagues would tell me, ‘Don’t worry, after this, your father will connect you’”, he remembers. “They didn’t know that I was fighting for my own space”.

Even when his father asked why he wouldn’t tell people that he was his son, Perliks refused. “I said no. When the time is right, they will know. I wanted to build my value first. I didn’t want anyone to work with me because of a name; I wanted them to work with me because they understood the value I bring”. That value would take years to build, and, as expected, the path wasn’t linear.

Finding His Own Language

The Fuji scene, despite its rich history, eventually bored him. “It was repetitive, and the audience didn’t care about the creativity of the video; they only wanted to see their favourite artiste”, he says. “I felt I could do more”.

So, he did something unusual. He started screenshotting still images from live Fuji performance videos of Pasuma and K1, then editing them into stylised photographs. He called himself an “editor of photography”, and people began sending him their photos to edit. It gave him traction at his JAMB lesson centre, where he met a photographer and began collaborating. But again, he wanted more. “I’m never satisfied creatively”, he says.

He researched, asked questions, and moved fully into photography, leaving Fuji completely. Using his father’s old Panasonic VHS camera, he began shooting small freestyle videos for friends who were artistes. Then one of those friends got signed to Mr Eazi’s Empawa program in 2020. They didn’t want him to spend much on a video, so Perliks offered to shoot it. The result was his first official music video, Macjreyz’s “Money Anthem”.

“When the video dropped, people were shocked. It looked like someone who had been preparing for years”, he recalls. The work spoke for itself. A friend who owned a production company saw it and started pitching jobs for him. He shot Lil Kesh, then Lyta, then others. “Everything started moving very fast, and I was ready for it. I just needed the platform”.

The Art of Intimate and Adaptive Storytelling

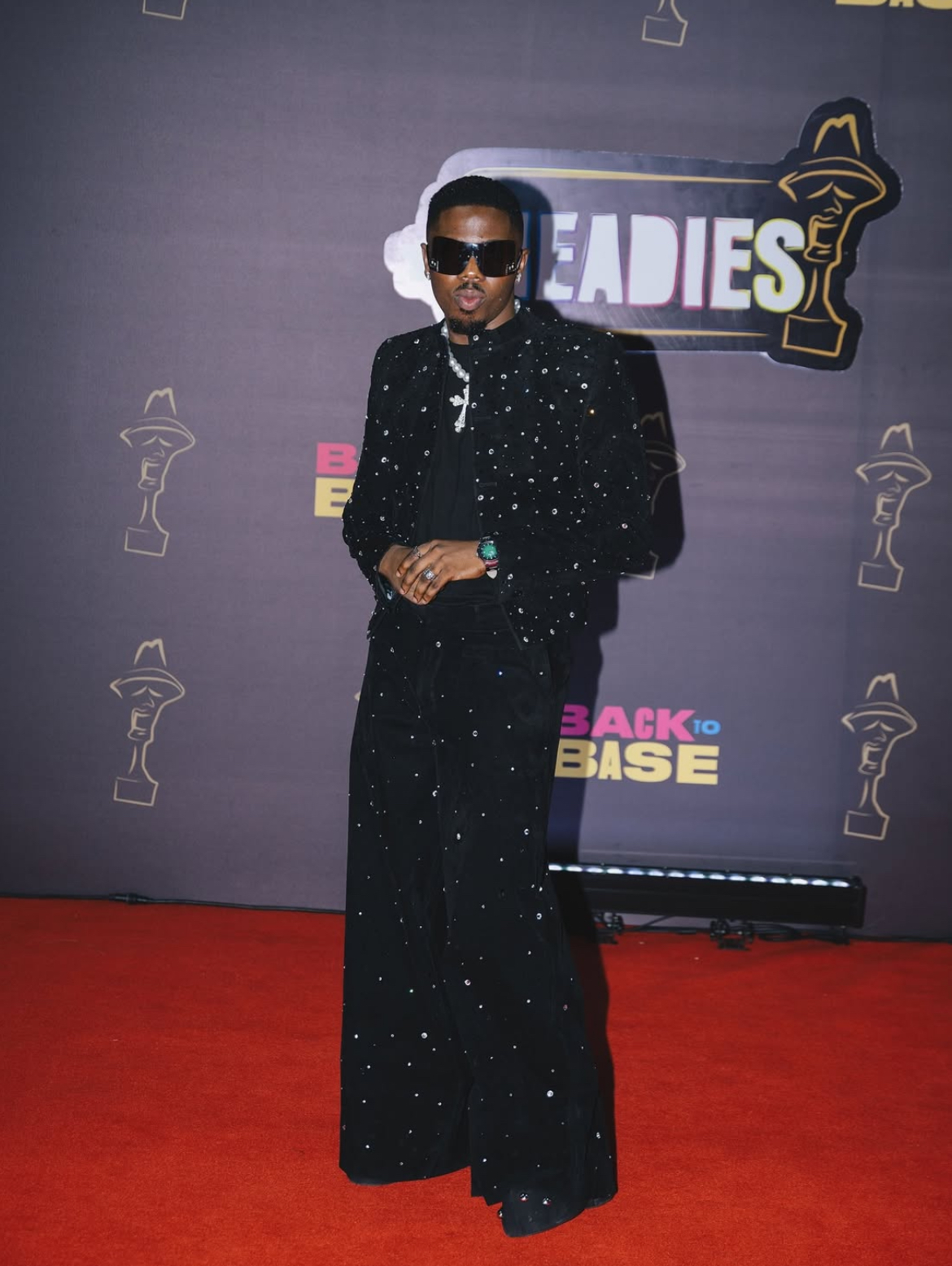

Recently, Perliks directed the music visuals for Adekunle Gold’s smash hit, “Many People”, off his newly released album FUJI, featuring The Tungba Creator, Yinka Ayefele, and Bonsue Maestro, Adewale Ayuba. It’s a well-executed video drenched in nostalgia. From Adekunle Gold’s Ankara jacket and Panama face cap (a tribute to Highlife legend, Fatai Rolling Dollar) to the intentionally imperfect green screens styled like old Fuji videos, complete with vintage text overlays and colour palettes, every detail transported viewers back to the genre’s golden era.

It was only then that Perliks began openly acknowledging his father’s legacy. “At that point, I knew my work carried its own weight”, he says. “Now, it feels like a proud thing, because there’s a connection because my dad did great work in his time, and I’m doing mine now”. He had wanted to co-direct the video with his father, but time didn’t allow it. Still, every frame honoured that era. “Who better to tell that Fuji story than me?” he says with a laugh during our video call.

But perhaps more revealing than the nostalgia was the philosophy behind it. When he listened to “Many People”, Perliks didn’t think about what visual tricks he could deploy or what signature style he could stamp on it. He thought about what Adekunle Gold was trying to say and how to make people feel it.

“I never take an idea I already have in my head and try to make the song fit that idea”, he explains. “Instead, I try to understand the artiste’s perspective, what they’re trying to say, the story they want to tell, and the feeling they want people to have”.

This approach has earned him criticism from peers who say he needs “one unique style” so people will immediately recognise his work. Perliks disagrees fundamentally. “If you watch “Kelebu”, “Fun”, “Coco Money”, and “Many People”, you won’t know it’s the same director unless you see my name, because each song demands a different approach”, he argues. “Different songs carry different moods. Some songs are just meant to make you feel good. Some are for reflection. Some are for love, heartbreak, sadness, or celebration. You can’t paint a sad-love story the same way you’ll paint a wedding song”.

For instance, in Adekunle Gold’s “Coco Money”, a song built around themes of wealth, with lines like “If you’re not spending money, go” and an interpolation of Rihanna’s 2015 iconic “Bitch Better Have My Money”, Perliks portrayed affluence in multiple forms without ever flashing cash. To him, wealth isn’t just money; it’s peace, presence, gratitude, and life.

For Young Jonn’s “Stronger”, off his debut album Jiggy Forever, a song that was trending as a dance track on social media, most notably as a widely used TikTok sound but originally dedicated to his late mother, Perliks made a choice that would shift how audiences understood the song entirely. “Many listeners didn’t know what it meant. So, as a director, I asked myself: How do I tell this story in a way that makes people feel even a little of the pain he felt?”

Instead of the predictable narrative, waking up with his mom, going to school, hustling, then losing her, Perliks structured the visuals to deliver an emotional punch at the moment of loss. “When he performs now, people turn on their flashlights because they finally get the message. That shift came from the music video”. This is where his 5% comes in: “I bring my own creative touch without overshadowing the artiste’s message”.

The Enduring Power of Music Videos

In an era dominated by short-form content, TikTok clips, and visualisers, some argue that music videos have lost their power. Perliks sees it differently. “The mistake people make is thinking music videos are about numbers”, he says. “If it were purely numbers, then the videos with the most views would be considered the best. But music video art is different. For those who truly understand it, music videos are about branding. They tell your story as an artiste. They shape how people perceive you”.

It is a perspective that aligns with broader conversations about the evolution of music videos in Afro-Pop. In a recent essay questioning whether music videos remain relevant in the genre today, I argued that Afro-Pop music videos no longer primarily serve to reach new audiences. Instead, they serve as tools to foster a stronger emotional connection to the artiste’s creative vision.

Perliks points to the past for evidence of this enduring power: “When you watched 50 Cent’s videos, you saw the puffiness, the muscles, the persona. When you watched D’banj, you saw Don Jazzy sitting like a Don. There was no social media to show you who they were, the videos did that branding”.

That purpose hasn’t changed, even if the landscape has. For Perliks, videos maintain their power in the streaming age, serving a different function than viral content. They deepen the emotional resonance of music, shape how audiences perceive an artiste, and provide narrative depth that fleeting social media clips cannot replicate

Crafting Timeless Stories

When asked what he hopes people take away from his work years from now, Perliks returns to the foundation of everything he does: storytelling.

“I believe my work should be timeless. My videos are built on storytelling, and storytelling never fades”, he says. “So, even years from now, I want people to watch my videos and still feel something, still connect with the emotion and the message. If the story holds them, if it makes them remember a feeling, then I’ve done my job”.

It is a humble aspiration from someone who’s shaped how millions experience some of the biggest songs in contemporary Afrobeats. But perhaps that insistence on being 5% while making the artiste’s 95% shine is precisely what makes Perliks exceptional.

He fought to build value independent of his father’s name. Now, both legacies stand side by side: Telemoon, who helped build Fuji’s visual language in his era, and Perliks, who’s doing the same for Afrobeats in his. Yet, his dream collaboration remains Chris Brown. It is the only collaboration that keeps him awake at night and the project he says will push him to his peak. “I don’t know if you can hear it in my voice, but I want that collaboration badly”, he says with palpable excitement. “Chris Brown is an all-around creative, crazy in the best way, and I feel like working with him would push me to my peak. After shooting a Chris Brown video, I will probably go and rest for three months because I would give it everything”.

Until that dream collaboration happens, he will keep making artistes shine, continually pushing the boundaries of music visuals with every project, and telling evocative stories that last.

Abioye Damilare Samson is a music journalist and culture writer focused on the African entertainment industry. His works have appeared in Afrocritik, Republic NG, NATIVE Mag, Newlines Magazine, The Nollywood Reporter, Culture Custodian, 49th Street, and more. Connect with him on Twitter and IG: @Dreyschronicle