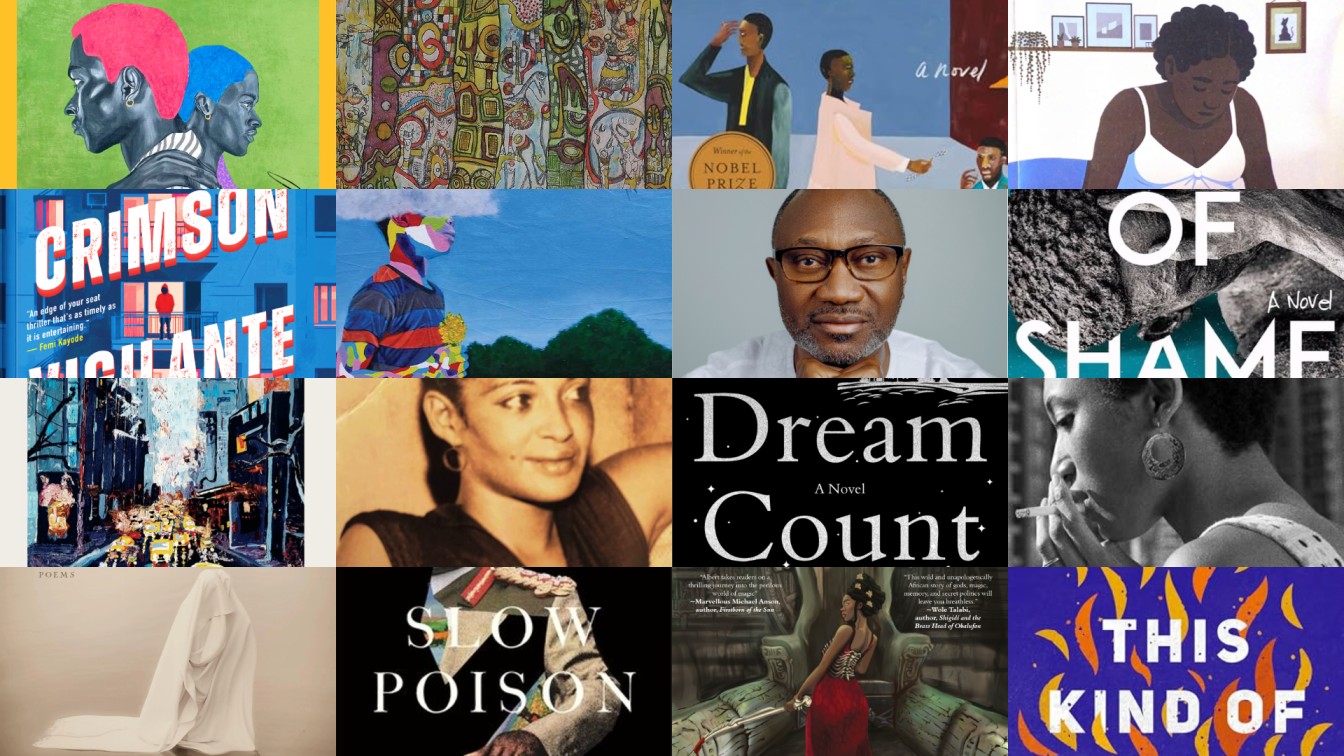

The good news is that African writers are still firing on all cylinders in all genres.

Afrocritik’s Literature Board

There is no doubt that 2025 began with high expectations from readers of African books, and particularly because one of the continent’s most famous writers, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, was publishing her first novel since Americanah came out in 2013. For the rest of the year, there was also excitement over other novels, poetry collections, and nonfiction books by both debutants and established African authors.

Literary book publishing in Africa has been seeing a steady rise over the past two decades or more, and the evidence of this can be seen in how these publishers have managed to make inaccessible books within easy reach of a local readership. Commendable too is how, increasingly in a country like Nigeria, debut authors are getting published locally first, before going international. More and more of this needs to happen if we want our book industries to continue growing. African traditional publishers also need to be more transparent with authors while strengthening distribution channels.

Most of these do not completely apply to South Africa, which has the continent’s most developed publishing and literary infrastructure, from which the rest of the continent can borrow a leaf. Why are we saying all these? Because, once again, many of the notable books this year are dominated by books published in the West. Diaspora, it seems, has remained the capital of our literature—a not at all ideal state of affairs, given that those who control means and capital in publishing decide which kind of stories get told. It is even more concerning when you realise that the ways in which this is done are insidiously benevolent and indirect.

Only after a period has passed do we begin to notice a tendency to always champion certain perspectives on Africa, telling and retelling the same stories in thinly veiled guises. “Authentic African stories” is an old formula tacked on a wall somewhere in a Western city, not the present lived experiences of Africans.

Thus, here at home, we need to speed up our drive to support our own stories; beyond that, we need to create the right environment for the right African books and the African right voices to come to the fore outside these shores. That is the one way we can begin to own our stories and retain the things in our languages and cultures that make us unique.

The good news is that African writers are still firing on all cylinders in all genres. This list has something for everyone, no matter the taste in literature. In no particular order, we present below Afrocritik’s Notable African Books of the Year 2025.

Fiction

Dream Count — Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Narrative Landscape)

Coming twelve years after her last novel, Dream Count was created with much fanfare (and had a mixed reception). It follows four women—three Nigerian and one Guinean—across different economic and social situations, whose lives intersect through personal history, romance, feminism, and sexual assault. Dream Count has been many things to different people, but it is also a moving story about the stereotypical paths down which many women’s lives go.

A Kind of Madness — Uche Okonkwo (Narrative Landscape)

A remarkable collection of short stories by Nigerian writer Uche Okonkwo, which mainly features child characters in prominent roles. In his review of the book on Afrocritik, Chimezie Chika writes: “make no mistake about the dynamism of the serious issues that topicalise these stories, Okonkwo suffuses just enough situational humour here, replete with Nigerianisms and the comic absurdity of pursuing the untrainable, believing the intangible, or keeping up appearances”.

Lonely Crowds — Stephanie Wambugu (Canongate Books)

In Lonely Crowds, Stephanie Wambugu turns to a searching intelligence, asking what it means to cleave one’s soul to another in an age restless with ambition. The long attachment between Ruth and Maria, begun in the cloistered discipline of a Catholic school and carried into the bright theatres of the 1990s art world, is rendered as a moral drama. One spirit burns outward, the other consuming itself inwardly. With a lucid style, Wambugu traces how class, talent, and longing arrange themselves into a private hierarchy of winners and exiles, and how the immigrant imagination learns, often painfully, the cost of worshipping brilliance.

How to Get Rid of Ants — Jesutomisin Ipinmoye (Parresia)

A Kafkesque collection that amplifies the bizarre, the weird, the insane, and the surreal. These are shown through everyday realities of characters in its fifteen stories: “a man in Abule, desperate to ‘hammer’ like his peers, risks everything for a shortcut to success; a young woman, weary of the endless pressure to marry, turns to magical matchmaking with unexpected consequences; a greedy man finds himself unable to stop eating, his hunger growing beyond control; and a Lagos-based graphics designer’s simple attempt to get rid of ants spirals into something far more existential. With a sharp wit, keen eye for the bizarre and highly stylised syntax, Ipinmoye reshapes familiar anxieties – ambition, love, survival – into haunting and unexpected narratives.”

Years of Shame — Obinna Udenwe (Purple Shelves)

Obinna Udenwe’s fourth novel is his best yet. The novel tells the tragic story of Patrice Ikebe whose fate is decided in the aftermath of an intra-tribal conflict. Afrocritik notes in its review that “on the basis of the idea of a story as something that stimulates memory and imagination, what he has offered us in Years of Shame is a tale that has a heart”.

Will This Be A Problem? The Anthology: Issue V — (Shilitza Publishing Group)

This fifth issue of Will This Be A Problem? gathered speculative tales as instruments for its clearer apprehension. Fantasy and horror performed the task of criticism: to see life steadily, and to see it whole, by bending myth, futurity, and dread toward the pressures of the present. Colonial afterlives, climate anxiety, technological unease, and the old brutal arithmetic of power. Edited with a deliberate refusal of leaning on the familiar speculative “heavyweights”, the anthology’s strength lies in its plurality, sixteen distinct moral imaginations, each asserting that Africa’s futures, real or imagined, cannot be told in a single register, nor by any single voices anointed as authoritative.

Promises — Goretti Kyomuhendo (Catalyst Press)

In Promises, Goretti Kyomuhendo approached migration as a pressure system that alters the climate of love itself. Moving between Kampala and London, the novel asks what becomes of intimacy when it is stretched across borders policed by law, poverty, and suspicion. Kagaba’s journey into the penumbra of illegal existence and Ajuna’s vigil at home are rendered with a chastened clarity: hope is neither romanticised nor dismissed, but tested, again and again, against circumstance. Kyomuhendo offers not consolation but understanding and an exacting portrait of how private vows fray when the world insists on making survival a solitary task.

A Meal is a Meal — Nnamdi Anyadu (Narrative Landscape)

In this debut collection of gothic food-themed stories, Anyadu’s imagination runs wide with both the macabre and the lightly comic. In twelve short stories, it is remarkable how Anyadu compresses the extraordinary into ordinary events and objects. This is fiction as fiction.

I Cry at the Feet of My Other Body — Mustapha Enesi (Witsprouts)

A provocative debut collection from a talented young writer and one of the first publications by the new publisher Witsprouts, the stories in I Cry at the Feet of My Other Body confront patriarchy and loss of agency. In her review for Afrocritik, Evidence Egwuono writes: “Across its thirteen short stories, the collection repeatedly centres the woman, foregrounding questions of agency and femininity such as these: What does it mean to exist as a woman in a society that objectifies before it recognises individuality? Where do personal desires intersect—or clash—with communal expectations? What happens when a woman asserts herself? And can autonomy ever exist without backlash? Enesi does not answer these questions in abstraction. Rather, he dramatises them through the lived realities of his female characters as each grapples with a hostile environment.”

The Tiny Things Are Heavier — Esther Ifesinachi Okonkwo (Masobe Books)

2025 saw the publication of this debut novel by Nigerian author, Esther Ifésinàchi Okonkwo. The novel follows Sommy, a Nigerian woman who moves to the United States for graduate studies. She finds solace in a biracial Nigerian, with whom she falls in love. Upon her return to Nigeria for the holidays, she is faced with truths about her family and identity.

Death of the Author — Nnedi Okorafor (Gollancz/Orion)

Nnedi Okorafor’s novel takes a different path from all her previous work. While still propelled by sci-fi and fantasy, Death of the Author, conflates metafictive elements wherein we are being told both the story of its author protagonist, Neely, and the story of the novel she is writing/wrote. As the two realities begin to merge in this near and distant future dualities, Nzelu’s private and public problems as a recent celebrity author begin to compound.

Harmattan Season — Tochi Onyebuchi (Macmillan Publishers)

In a fantastic novel that blends crime, noir, and elements of sci-fi, Onyebuchi tells the story of a private investigator who sets out to investigate the sudden disappearance of a bleeding woman. What he finds out is a paranormal event creating levitating corpses and city blocks in the city, and an ancient plan by an underground revolutionary group.

A Season of Light — Julie Iromuanya (Little Brown)

For Fidelis Ewerike, trauma seemed a relic of the past, replaced by a secure life in Florida. But the news of over 200 girls abducted in Nigeria reawakens memories of his own displacement during the Nigerian Civil War. Anxiety grips him, and his mental health deteriorates rapidly, casting a shadow over his family. His daughter bears the brunt of his unease, and in a desperate attempt to protect her and to avoid reliving his sister’s disappearance, he confines her to the home. A Season of Light explores how one family struggles to navigate life while carrying the weight of a dangerous and haunting past.

The Bone River —Nkereuwem Albert (Ouida Books)

In Nkereuwem’s book, anything is possible. Calabar, where the novel is set, becomes more than a place; the city also becomes an active character, where magic permeates everyday life. Four powerful houses uphold a fragile pact that forbids them from turning on one another. When unsettling incidents begin to threaten this Secret Peace, Afem is tasked by her father, the Bone Chief, to uncover the source of the disturbances. Her investigation forces her into an uneasy alliance with Heych, a former friend she deeply resents, as the two must set aside their hostility to prevent the collapse of the pact. The Bone River draws from Efik and Ibibio mythologies, blending them into an urban fantastical book.

This Kind of Trouble — Tochi Eze (Masobe Books)

Tochi Eze’s debut, This Kind of Trouble, opens in 2005 Atlanta with 67-year-old Benjamin Fletcher reflecting on a transnational life shaped by England, Nigeria, Ghana, and the United States, and questioning how three marriages led to solitude. The novel traces his ancestral roots to Umumilo in southeastern Nigeria, roots he shares with his first wife, Margaret Okolo, whose fractured marriage with Benjamin drives the book’s inquiry into fate, choice, and inherited history. Moving backwards through time—from 1960s Lagos to Umumilo in 1905—the novel reveals buried family entanglements, mental illness, colonial disruption, and communal violence. Eze’s expansive, non-linear narration links generations to show how the past remains present yet ultimately unknowable.

The Edge of Water — Grace Olufunke Bankole (Masobe Books)

At the centre of this novel is Esther, whose life story unfolds through letters written to her estranged daughter, Amina. Esther recounts her youth, her coerced marriage to Sani following sexual assault, and her determination to create a better life for Amina. Her decision to leave Sani and build independence through her restaurant marks a turning point, though she remains burdened by fear and a need to control her daughter’s fate. Seeking answers, she turns to both Christianity and traditional spirituality, setting hidden truths in motion.

Amina’s parallel story follows her coming of age amid misunderstanding, betrayal, and strained family relationships. Her desire for freedom eventually leads her to migrate to the United States, where her expectations collide with reality.

The Edge of Water by Grace Olufunke Bankole is a multi-generational novel rooted in Yoruba spirituality, where divination shells serve as guiding, near-omniscient forces shaping the lives of its characters. In reviewing the book, Evidence Egwuono writes: “The Edge of Water asks what it means for women to be bound by blood and spirit; connected across generations, yet separated by distance, and the inevitable drift of time”.

Necessary Fiction — Eloghosa Osunde (Masobe Books)

Necessary Fiction is an expansive and ambitious novel that centres queer chosen family as both its subject and organising principle. With a vast cast of characters including artists, lovers, and entrepreneurs, it constructs a community sustained by art, vulnerability, money, and radical loyalty. Opening in grief, with the deaths of fathers and the loss of childhood innocence, the novel follows characters forced to mature early as they learn to parent one another in adulthood. Death, trauma, and the spirit realm permeate the narrative, while art becomes both a means of survival and a site of danger. Necessary Fiction positions itself, ultimately, not as escapist storytelling but as a healing practice. Here, fiction is survival, intimacy, and collective recognition.

Theft — Abdulrazak Gurnah (Random House)

Theft traces the intertwined lives of Karim, Fauzia, and Badar as they navigate love, duty, and inequality in Zanzibar and mainland Tanzania. Karim, shaped by his mother Raya’s failed marriage and remarriage, returns from university to reunite with Fauzia, once frail but now a confident teacher-in-training, and marries her. Badar, sent away at thirteen to serve due to his adopted parents’ poverty, grows up burdened by abandonment and the mystery of his biological father. When Karim later offers him work, Badar feels a profound indebtedness. The novel explores how debt—financial, emotional, and ethical—can turn generosity into control, highlighting power, dependence, and the hidden violences beneath benevolence in a transforming Zanzibar.

The Dream Hotel — Laila Lalami (Pantheon)

The Dream Hotel by Laila Lalami is a near-future dystopian novel about surveillance, privacy, and bureaucratic control. Sara Hussein, a Los Angeles museum archivist and mother of twins, uses a neuroprosthetic Dreamsaver to manage insomnia, unaware it harvests her dreams. After dreaming of harming her husband, she is detained under a government risk-score system predicting criminal intent. At the private Safe-X retention facility, she faces indefinite incarceration, forced labour, and opaque, algorithm-driven rules. Echoing Kafka and Philip K. Dick, the novel critiques surveillance capitalism, algorithmic policing, and the commodification of intimate thoughts, raising urgent questions about autonomy, privacy, and systemic power.

Buried in the Chest — Lindani Mbunyuza-Memani (Jacana Media)

Lindani Mbunyuza-Memani’s debut, Buried in the Chest, follows Unathi, a young woman in rural Moya, Eastern Cape, raised by her grandmother while her mother is absent. Set during South Africa’s democratic transition, Unathi confronts the legacies of racial oppression and personal loss, seeking her mother to reclaim her identity. Across three acts, Unathi moves from village life to teaching college and encounters with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, navigating self-discovery, love, and loss. Mbunyuza-Memani’s evocative writing makes this a compelling and emotionally resonant debut.

Everything is Fine Here — Iryn Tushabe (House of Anansi Press)

Iryn Tushabe’s debut, Everything is Fine Here, follows 18-year-old Aine in present-day Uganda as she grapples with her lesbian sister’s persecution, oppressive religion, and gender inequality. Determined to challenge her mother’s rigid Christian beliefs, Aine navigates family tension and societal constraints, growing in awareness of gender, sexuality, and justice. Tushabe vividly depicts Uganda’s landscapes and urban hardships, immersing readers in its realities. Despite occasional digressions, Aine’s reflections on religion and human nature resonate deeply. The novel concludes with hope and agency, symbolised by a Rukiga proverb, establishing Tushabe as a courageous and compelling new literary voice.

The Crimson Vigilante — Olayinka Yaqub (Masobe Books)

In Olayinka Yaqub’s debut novel, Tomiwa Solade, a dedicated officer in the Nigeria Police Force, faces his toughest challenge when a merciless killer begins targeting the city’s elite. Tasked with solving the case alongside his fractured team—loyal yet haunted colleagues Simi and Jubril, and the enigmatic Bidemi Lawal—he must navigate a labyrinth of secrets, political corruption, and personal vendettas. As the body count rises, Tomiwa confronts not only a cunning adversary but also his own unresolved past. This intense, suspenseful thriller examines betrayal, family ties, and the pursuit of justice.

Bitter Honey — Lola Akinmade (Masobe Books)

Lọlá Ákínmádé’s Bitter Honey explores generational trauma, love, and selfhood through the intertwined lives of Nancy and her daughter Tina. The novel opens with a shocking image of psychological unease, setting the tone for Tina’s discovery that her father, long thought dead, is alive. Nancy, a Gambian scholar in Sweden, navigates loneliness, racial isolation, and a morally fraught romance with her professor Lars, whose obsession derails her ambitions and shapes Tina’s emotional inheritance.

Moving between past and present, the novel examines family secrets, betrayal, and the long shadow of parental choices. Tina faces public scrutiny, racial bias, and emotional turmoil, repeating patterns of longing and validation learned from her mother. Åkínmádé’s prose is evocative, depicting the complexities of desire, ambition, and moral compromise.

Qwani 04: Nairobi Edition — (Qwani)

If the hesitations of Qwani’s early volumes are granted their due, then the assurance of this fourth edition deserves equal praise. Qwani 04: Nairobi Edition captures Nairobi not as a postcard or cliché, but as lively, noisy, improvisational, and perpetually unfinished. Through stories, poems, and images, the anthology contributors examine a city with an honesty that resists nostalgia and cynicism. The result is a book that understands the city as a culture itself, a conversation in motion, where the young test language and form in order to discover what, amid the rush, might still be worth holding onto.

We Shall Remain: The Gerald Kraak Anthology Vol V (Jacana Media)

We Shall Remain stands as a resolute chorus, affirming that African writing on gender, sexuality, and justice is not a marginal literature but a central reckoning with how societies imagine their moral future. The anthology’s strength lies in its breadth of form and temperament, each work participating in what you might call “the best self”. By gathering voices, the volume once more does more than commemorate Gerald Kraak’s legacy. It insists that dignity, once articulated, becomes a cultural fact, contested, yes, but no longer deniable.

Nonfiction

Slow Poison: Idi Amin, Yoweri Museveni, and the Making of the Ugandan State — Mahmood Mamdani (Harvard University Press)

With Slow Poison, Mahmood Mamdani undertakes the austere labour of thinking against habit, refusing the shortcuts that have been witnessed in narratives of postcolonial Uganda. Blending memoir with political analysis, he places Amin and Museveni not as caricatured opposites but as divergent practitioners of violence within a single, unfinished project of decolonisation. The book’s provocation lies less in its conclusions than in its method, which is a steady, unsparing inquiry into how power secures legitimacy, how Western approval is earned, and how nations are hollowed from within while praised abroad. This is criticism as seriousness of purpose and a work that disturbs received opinion in order to recover the possibility of truthful judgment.

How Depression Saved My Life — Chude Jideonwo (Narrative Landscape Press)

Episodes of #WithChude, Chude Jideonwo’s talk show, are often characterised by moments of openness and rare vulnerability and, occasionally, with celebrity guests bursting into tears. In this revelatory memoir, Jideonwo shares how a period of depression led to the birth of this show, and how he has been able to elevate a time of immense suffering to a platform that speaks to thousands of people across the continent and beyond.

Mrs Kuti — Remilekun Anikulapo-Kuti (Ouida Books)

In the posthumously published memoir, Mrs Kuti, Remilekun Anikulapo-Kuti, offers up a portrait of her coming of age, her life and times with the legendary musician and activist, Fela Kuti. The memoir brings to the fore the often ignored problematic treatment (and opinions) of women by Fela, despite his activist status, and in doing so, opens up broader conversations on our relationship with our National figures and the excuses we as a people make up for the talents of questionable behaviour. In her review for Yabaleft Review, Yẹ́misí Aríbasálà, puts it better: “Should one bother to listen to (pay for) music fashioned by men who offer no substantial advantages to women, no elevation, or even reduce and derogate women in their lyrics and lifestyle?… Men in power mishandling young women is an au courant theme. We take it for granted in Nigeria that money and professional success permit men to misbehave sexually and criminally, especially where it concerns young, underage girls.”

Another Mother Does Not Come When Yours Dies – Mubanga Kalimamukwento (Wayfarer Books)

Hailed as a “kaleidoscope of emotions”, award-winning Zambian author, Mubanga Kalimamukwento, confronts unimaginable loss in Another Mother Does Not Come When Yours Dies. In this eclectic hybrid collection, Kalimamukwento, aided by the Bembe proverb—tapafwa noko, apesa umbi—chronicles her “experience of maternal loss, and the perpetual cavity left by this premature orphanhood.”

The World Was In Our Hands: Voices from the Boko Haram Conflict — Chitra Nagarajan (Cassava Republic Press)

Editor and activist, Chitra Nagarajan, delivers harrowing insights on the lives of those living through the Boko Haram crisis with The World Was In Our Hands. This important collection goes beyond news coverage to present the story of the horrors of Boko Haram directly from those whose lives have been eternally changed by this devastating crisis. In their thematic preoccupations, these stories are wide-ranging, covering climate change, corruption, patriarchy, and the economy.

Making it Big: Lessons From a Life in Business — Femi Otedola (Narrative Landscape Press)

In this memoir by Nigeria’s billionaire businessman, Femi Otedola, he tells the story of his rise as a magnate, beginning his first steps at 10 years old and making his first billion at 41. The book also functions as a business book. It goes into the technicality of running and making a business work, successes and failures, etc. The book also spends a considerable amount of time on Otedola’s entrance and success in the oil industry. It had its controversies, generating conversations around privilege (where a tweet on X pointed out that his successes may have had more to do with his privilege than his hard work).

Poetry

The Naming — Chinụa Ezenwa-Ohaeto (University of Nebraska Press)

In many cultures across the continent, names and the act of naming itself, is a prayer, a plea and a prophecy — for what a child is and is to become. In Ezenwa-Ohaeto’s debut collection, he invokes patrilineal ancestral ties and lineage. Ezenwa-Ohaeto dialogues with the past, seeking what it means not only to know, but to understand one’s heritage.

Bakandamiya: An Elegy — Saddiq Dzukogi (University of Nebraska Press)

From the winner of the Derek Walcott Prize for Poetry comes Bakandamiya, an ambitious epic in the tradition of Hausa griots. In lines bristling with lyrical beauty, Dzukogi engages the mystical, praying and praising, tackling important questions on culture, spirituality and nationhood.

Fenestration — Othuke Umukoro (Texas Review Press)

Fenestration investigates the public and the private, engaging a multiplicity of themes: familial ties, migration, HIV, memory, amongst others. Tracie Morris, a professor of Umukoro’s at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Tracie Morris, praises the collection: “Othuke’s heart-centric new work…is filled with tender poems of discovery. They stay with the reader long after the end of a page and the book. The strength of these poems is in the refined delicacy of understanding, through dilated pupils, the bayonets’ knife-edge. Both through the intimacy of complex love between father and son, and the sweeping and intimate pain of those Africans whose involuntary journeys created the African diaspora we know today, we comprehend what it means to perceive the world through haunted, multi-century somatic knowing”.

The Years of Blood — Adedayo Agarau (Fordham University Press)

In Years of Blood, Agarau pays homage to the kidnappings of his childhood. Using memory as a conduit, he traces the contours of the football playing days at Ogunleye Street, the heart-rending loss of the “dead band of boys”, and what trauma does to a body that is yet unable to articulate it.

African Urban Echoes — Jide Salawu and Rasaq Malik Gbolahan (eds.)

African Urban Echoes attempts to capture the pulse, rhythm and voice of African cities. And in this attempt to know a city, the poems present snapshots into understanding the people who inhabit these cities. Editors Salawu and Gbolahan seek to know “how these urban centres carry the heritage of colonial violence in their walls, roofs, texture, and rhythms. How can we create stories that inspire a lifeworld not of struggles to counter the normativized narratives of African urbanity? What other forms of cities do we have and hope to live in?”

Phases — Tramaine Suubi (Harper Audio)

In Phases, Tramaine Suubi converts the ancient grammar of the moon into a lens for emotional reckoning, tracing how grief, desire, and endurance wax and wane within the human spirit. The poems move with a deliberate lyric intelligence, attentive to the body’s testimonies and to histories carried, often wordlessly, by Black women across generations. What distinguishes the collection is its refusal of haste, as pain is neither sensationalised nor hurried toward resolution, but allows its proper duration, its necessary darkness.