[In The Naming,] Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto wants to say something of his Igbo background. . . [And] the most important point to be made is perhaps that the poems [in African Urban Echoes] lack a sense of intimacy—an intimacy of the known.

By Ernest Jésùyẹmí

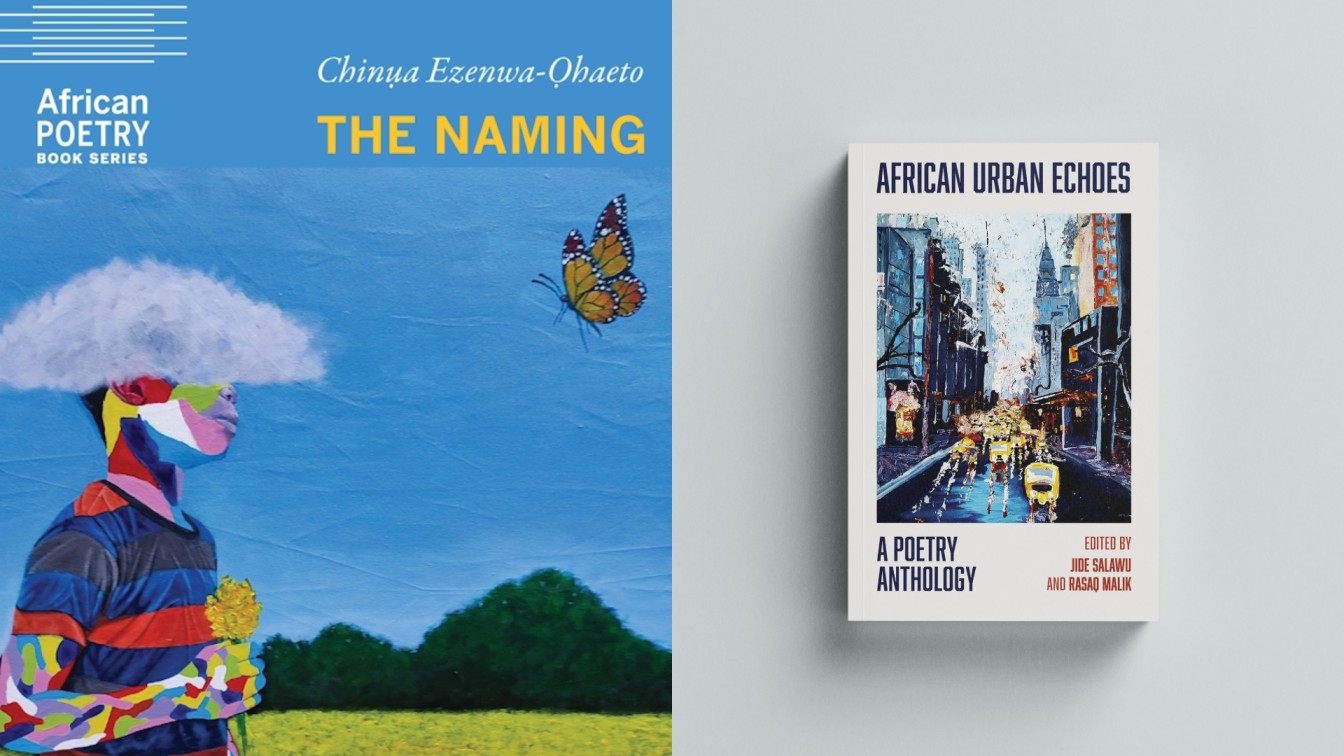

Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto “names” a great many things in his debut book of poems, The Naming (2025). Some of what he names are the usual things a reviewer has learned to expect from a collection by a Nigerian: “events” relating to the Aba Women’s Riot of 1929, the Nigerian Civil War, the slave trade, terrorism, etc. There is no end to being bored by reading the same sterile, stereotypical things in every new book, but one learns to make peace with it. One prays, as the poet does in “Mercy”, “Chukwu biko zienu, let patience and restraint find me as I find them”.

After beseeching God, one consoles oneself with this: “At least we are trying. We are trying to say something about our history”.

But then I think about this telling statement from Robert Wren’s Those Magical Years (1991): “But I say again, that in terms of concrete knowledge of the African background, we knew next to nothing really. Next to nothing”. This was Abiola Irele, the well-known scholar of African literature, and by “we” he meant his contemporaries—the first generation of Nigerian writers.

When the writers of the Achebe generation went to University College, Ibadan (now the University of Ibadan) in the 1950s, they barely knew anything about their own cultures. And yet, in a few short years (Things Fall Apart was published in 1958), they had begun to produce work that was hard to ignore, drawing from an understanding of the same culture. How did they do it? And why, compared to them—we who have degrees from American universities, where the libraries are filled with books that were not yet written in Chinua Achebe’s day, we who have their example—why do we consistently underperform?

Like those writers, Ezenwa-Ohaeto wants to say something of his Igbo background. He writes in “Chinualumogu Sits on His Balcony Pretending He Is a Parcel” (witty title, witty first line), “For years, hands have been blacking out our history / and our pasts have been asking for ordinance and recalling”. He takes it as his task to “recall” what has been forgotten; and, as a wise son, he asks the help of his ancestors (whom he refers to as “our fathers’ fathers”).

In his pursuit of that admirable aim, the poet comes up against some difficulties.

Though Achebe is mentioned only once, his presence hovers over The Naming. He is the standard for Ezenwa-Ohaeto, who does not have any of the novelist’s gifts.

The poet has no narrative ability. To set a scene, to pace judiciously, to intrigue: these are skills he wants. Take “Okụzụ”, a poem where he “retells” a story told to him by a friend. It’s about two brothers at the outbreak of the Civil War. One of them gets badly wounded in a strike in Enugu; the other rides his bicycle to Okụzụ to carry his kindred back. The germ of a story is probably in this, but it is not, as I have told it (which is how the poet tells it), a story. You read it and ask, “So what happened?” “Did the brother live?” “Did he die?” “Did they both survive the war?” In the poem, nothing. No epiphany.

Next, he comes up short as a translator. Achebe was a great translator: of one culture into another, and of one language into another. Ezenwa-Ohaeto tries to do this, too. The result is more like Gabriel Okara’s in his translations from Ijaw, which J. P. Clark-Bekederemo said read like “an artificial stilted tongue, more German than Ijaw”. Ezenwa-Ohaeto writes: “give us the needed to un-monkey the / monkey’s hand monkeying us badly, and even / the monkey’s hand yet to monkey us” (“A Call’s Dusk”). Not all his efforts are this out-of-tune, but he generally lacks the perfect simplicity (and felicity) of phrasing that makes Things Fall Apart what it is.

One of Ezenwa-Ohaeto’s desires is to take things easily—life and its discontents high up on the list. But writing with that kind of ease can make a poem very dull. Although the man has a comedic gift—a dry, galvanising humour—it is currently under-explored.

“A Page from Chinualumogu’s Diary” uses the kind of humour. “A young man gave me a microphone one afternoon. / He wanted me to be heard. / I screamed Love into it and everyone ran away. / It didn’t come out well, he said. Try another word.” Consider the interplay of “heard”, “screamed”, and “It didn’t come out well”. You want me “to be heard”; I “scream” to make sure no one says they did not “hear” me (but also because I am anxious to say my bit); you say, “That didn’t come out well”. Okay, let me say it again, without the impatience this time. No. The young man says, “Throw that word away and pick another one”.

The pretensions and hypocrisy of platforms and platform-givers, the hypocrisy of a world that cannot tolerate truth, and the naive intensity of youth (which usually causes distress), all of it is in those few lines. The “I” of the poem is young and has much to learn. Yet, he cannot “see clearly”, as an uncle tells him in the poem. He has some growing up to do. Beer is used to short-circuit the process. The uncle, handing him a bottle, says, “rinse your mouth with it” (a brilliant, cutting phrase).

The ending is a small epiphany: “Now that you see clearly”, the uncle says, “can you see how the moon is also the sun?”

The poem will likely survive the book.

II

Last year, the Nigerian poets Olajide Salawu and Rasaq Malik Gbolahan put together an anthology of city-poems, African Urban Echoes (2025). It’s a commendable effort, and its reach is noteworthy. Lagos has the most poems (the cheat), but Osogbo, Kaduna, Port Harcourt, Warri, Lomé, Cape Town, Accra, “Jburg” (as Jumoke Verissimo tags it in her poem of that title), Addis Ababa, Nairobi (and more) are represented. For a better perspective, the editors also took the pains to include poets of an older generation: Gbemisola Adeoti, Tanure Ojaide, and Tade Ipadeola are in it.

More than half of these poets, both old and young, are either writing back home or away from home. Some write as migrants; others as tourists. In “Mine Too is Karama”, on New Year’s Day in New York City, Ber Anena says her family’s “laughter”, flying Memory Airways, “reaches me without visas”. After descending that plane, Ojaide asks in “Warri & I”—“Can I still be a Warri Boy after the countless years that / I have abandoned its wonderful staple to be an itinerant lover?”

The relation the contributors have to the places they write about shows in the way that they do the writing. The most important point to be made is perhaps that the poems lack a sense of intimacy—an intimacy of the known. Those who write from home-home are just as interested in giving the reader information (see “Cape of Storms née Good Hope” by Brindley J Fortuin, written as a series of tweets). The poems come out as descriptions of places, something to be used by a visitor to a city; and the strokes are hurried.

Here is “Oxford Street, Accra” by Verissimo (in full):

“clothes and hotels

tourists and owners

tro-tro

billboards and frozen smiles—traders too afraid to frown

fun and fast-food

hunger isn’t meant to be a thing if you call the figure rightfirst time tourists learning to memorise a lifetime story of Africa

on a street that says: choose your feel

for this street is a synecdoche

of the unexplored city and its desires”

What the poet pokes fun at in the tourist, she also does. Verissimo’s poem (like others in the anthology) is itself “a synecdoche for the unexplored city [of Accra] and its desires”. The best the poet has done here is to gesture towards the city’s secrets and longings. She has not “explored” either one.

For a poet, a few strokes (“clothes and hotels / tourists and owners”) will never do. Even in cases where the words are more profuse (“Oshodi”, Gbemisola Adeoti), the piece reads like a sketch. What one gets out of that method is a picture, a portrait of sorts, which is easy work. (It is the bare minimum.) Sometimes, as in Ridwan Badamasi’s two poems (“Palimpsest”, “Wednesday Market”), the writing, though descriptive, gives pleasure: “Beyond the rice patches, the gentle waters kiss the rough bank”. But Badamasi, like Verissimo, knows that this is not enough. “The city is full of shy ghosts”, he writes. One may retort that they are not so “shy”; it is the poet who has not done a good job trying to woo them.

What is needed to woo a city and its ghosts, so that they show, as we say in Nigeria, their true colour?

Language, always. Language that encompasses the picture, that is surplus in its apprehension. And, too, language that is sensitive to what goes on behind the shows a city puts up; that discerns its inner workings. One way, and a sure way, is through the lives of people, their collisions with one another. But it takes some hard searching to come upon people in this anthology. The poets are very busy with their cameras. No shaking of hands. No one catches a pretty eye. The cities are said to be “bustling”, but they remain, for us, quite unalive, since what makes a city alive are the bodies that move through it.

We meet a man in Nurain Oladeji’s “The Statesman”. His name is Gboyega Oyetola, the former governor of Osun state, who lost a re-election to Ademola Adeleke in 2022. He is not in the poem directly; he is in it as a presence (and as a cautionary tale). The poem begins: “Morning after the governor lost reelection, / I returned to the capital”.

In Osogbo, they drove

“into an assault

of the governor’s face wailing at us from all sides.

Here, in purple t-shirt, shaven, he meant to look

youthful. And here, bright in matching helmet

and reflective jacket, arms folded across his

chest, he meant to show he’s hands-on.”

The governor continues to appear, and Oladeji details each pop-up. To what end? “All that ubiquity and the people still looked away”. The entire poem was driving, as the bus he was in drove, towards “the people” and their refusal to be “assaulted”, to be cajoled into liking the man. The “looked away” has the weight of a political statement.

The last line of Kola Tubosun’s “Night Road” has this sensitivity, too. The poem is familiar, the idea being “Tread carefully” while travelling on Nigeria’s “perilous roads.” In the poem, by the roadside is a “freshly minted corpse”. The phrase “freshly minted” (or “fresh mint”) always refers to money that has just come off the machine, smelling like newly-baked bread. Its usage here calls attention to itself. The simple meaning is that the man has just died. But in another light, it may be callous and insensitive language—cleverness gone too far. Looking again, one asks: Is the poet saying that death is expensive? Not quite (the cost of a life cannot be expressed in monetary terms). The real point I think Tubosun has sneaked in here is that, for each person who dies on one of those roads the government has refused to fix, someone somewhere smiles to the bank.

M. L. Kejera’s “Carthago Delenda Est” is exceptionally alive to history and to its place. It is a savvy, well-saturated, judicious poem. The title, meaning “Carthage must be destroyed”, is said to have issued from Cato the Elder (234 BC—149 BC). Kejera uses the phrase to draw attention to disturbing developments in Tunisia, where he grew up. In February 2023, Kais Saied, the president, said sub-Saharan African migrants in the country were part of a plan to replace the Arab-Muslim population. Migrants were cast out of their homes by landlords and assaulted by nationals.

“I have walked Carthaginian streets older than names of God upturning stones, profaning relics, tearing out pages, fingering lacunae, demanding-asking-pleading why must a city be destroyed? Why would a man punctuate his speeches with war? There are drops-of-red caked over granulated silk”

The silk is the dress of a woman who, with her child, has been “sacrificed to borders”. Kejera asks again, posing his question differently, “What law-edict-pillar says a city must be spared?” This time it is a cry for empathy: Why should a city be protected from the coming of migrants? His vision for the city is a democratic one. The people are ripe for it: “Did I not hear my neighbour yell ‘La democratie va gagner!’” (Democracy will win.) But the leader(s) are not. Any progress made on that front is tentative: “Xenocide is patient in the kiln, forever awaiting the match, forever piling wood”. The poem demonstrates the “forever” form that violence takes.

One is grateful for a new anthology with a focus, like this one. African Urban Echoes, whatever its weaknesses, has furnished African poetry with a few new poems to hold close for some time.

Ernest Jésùyẹmí is the author of A Pocket of Genesis (Variant Lit, 2023). His work has appeared in AGNI, The Sun, Poetry London, The Republic, and Mooncalves: An Anthology of Weird Fiction. He holds a BA in history and international studies from Lagos State University, Nigeria, and is the poetry editor of EfikoMag.