The battle over A Very Dirty Christmas might seem small in the grand scheme of things, but they’re symptoms of a larger struggle over who controls cultural meaning in Nigeria’s public sphere.

By Joseph Jonathan

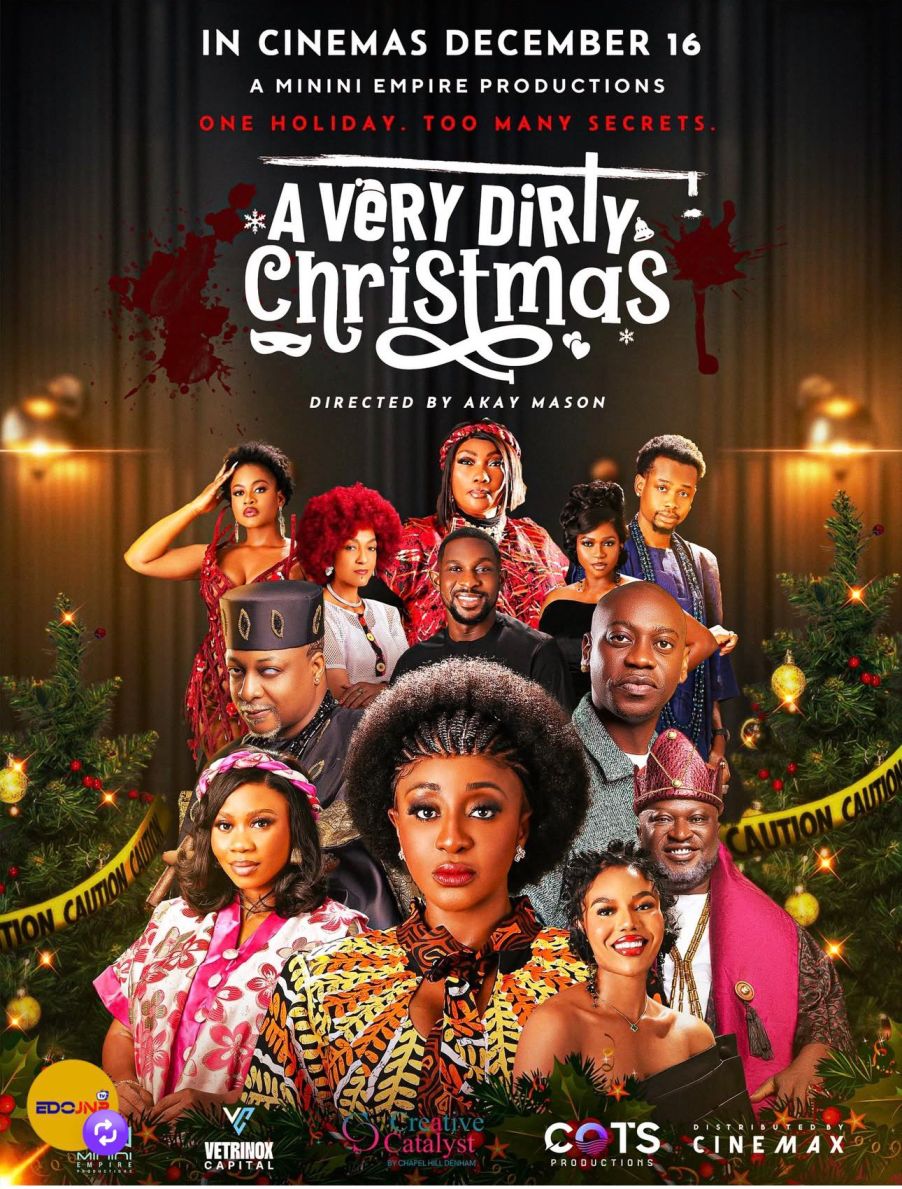

A Very Dirty Christmas arrived in Nigerian cinemas in December 2025 as a fairly conventional holiday release. Produced by Ini Edo, directed by Akay Mason, and written by Juliet Iwuoha, the film was positioned as a festive drama-comedy about family dysfunction, buried secrets, and the emotional negotiations that surface during reunions.

Yet, what came to define the film’s public life was not its narrative, performances, or aesthetic decisions, but its title. Two days after the film was released in Nigerian cinemas, the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) publicly condemned the phrase A Very Dirty Christmas, describing it as offensive and disrespectful to Christian values. The backlash triggered regulatory conversations, public apologies, and a broader debate about religious symbolism and artistic freedom in Nigeria.

What makes this episode worth interrogating is not whether the title was tasteful or provocative. It is what the reaction reveals about how meaning, offence, and authority are negotiated in Nigerian public culture, and how cinema becomes a battleground for these negotiations.

CAN President Archbishop Daniel Okoh’s statement was unequivocal. Linking Christmas with the word “dirty”, he argued, “diminishes its spiritual significance and reduces a solemn religious observance to something crude and sensational”. The association didn’t need to see the film. The title alone was enough.

The statement set off a chain reaction that would see Ini Edo apologising repeatedly, the National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB) requesting modifications, and an entire industry watching to see how far religious institutions could reach into creative spaces.

This is the central paradox of symbolic policing: it operates on surfaces. A title. An image. A costume. These become stand-ins for entire arguments about morality, faith, and national values; arguments that rarely require engagement with the actual work. When pressed, Ini Edo explained that “dirty” was metaphorical, referring to the family secrets that emerge during what should be a joyous season. She described Christmas as a time that “often reveals the contrast between appearance and truth, joy and struggle, virtue and human imperfection”.

On the surface, it’s not so shocking that CAN reacted the way they did to the film’s title. Christmas occupies a peculiar symbolic position in Nigeria. It is religious, familial, commercial, and cinematic all at once. December is the peak of Nollywood’s theatrical calendar, a time when diaspora audiences return home, cinemas are packed, and films are marketed as cultural events. At the same time, Christmas is rhetorically framed as a season of purity, reconciliation, and moral clarity.

A Very Dirty Christmas disrupts that framing at the level of language. The word “dirty” introduces messiness, imperfection, and moral ambiguity: qualities that are intrinsic to human relationships but uncomfortable when attached to sacred symbols. The outrage was therefore less about narrative content than about symbolic contamination. The title suggested that Christmas, and by extension Christian domesticity, could be represented as flawed, chaotic, and human. That suggestion collided with a public discourse that prefers sacred seasons to remain linguistically and aesthetically pristine, regardless of lived realities.

CANʼs stance wasn’t an isolated incident. It was the latest expression of a pattern that runs through Nigerian cinema like a fault line; one where religious groups, both Christian and Muslim, have positioned themselves as arbiters of meaning, reacting not to content but to symbols, titles, and images that trigger offence before a single frame is viewed.

17 months earlier, in July 2024, actress Nancy Isime had faced a remarkably similar controversy, this time from Muslim groups. The promotional poster for her yet-to-be-released film Blood Brothers showed women in niqabs (face veil worn by Muslim women) holding guns in what appeared to be a bank robbery scene. The backlash was immediate and fierce.

The Muslim Rights Concern (MURIC), led by Professor Ishaq Akintola, described the film as “satanic”, “Islamophobic”, and capable of “setting Nigeria on fire”. Their statement was blunt: “This film is aimed at portraying Muslim women as criminals with a violent proclivity. It is designed to incite Nigerians against Muslim women, make them appear as violence-prone desperadoes and stimulate hostility against them”.

Once again, the NFVCB responded swiftly, not with regulatory firmness but with accommodation. Director-General Shaibu Husseini announced that the board had contacted the producers and was making efforts to have the complaints resolved. The film, still in production and not yet submitted for classification, was already being modified based on religious objections to promotional materials.

Place these cases side by side, and a pattern emerges. In both instances, religious groups reacted to symbols, not content. CAN condemned a title. MURIC condemned a costume. Neither group needed to watch the films to declare them offensive. The symbolic juxtaposition of “dirty” with “Christmas” and the image of niqab-clad women with weapons was offensive enough.

Regulatory bodies deferred to religious pressure. Despite having legal frameworks and professional committees, the NFVCB consistently yielded to faith-based complaints. Their official statements emphasised “religious sensitivity”, “diversity”, and “preventing tension”: language that positioned creative work as a potential social threat and religious institutions as guardians of public peace.

Creators bore the burden of proof. Both Ini Edo and Nancy Isime found themselves having to explain their artistic choices, defend their faith credentials (Edo repeatedly emphasised being a devout Christian), and offer to modify their work. The presumption wasn’t innocence but potential blasphemy, an inversion of creative freedom where artists must prove their work won’t offend rather than critics proving it actually does.

What these controversies reveal isn’t really about Christmas or niqabs. It’s about definitional authority in a religiously plural society where faith institutions wield enormous cultural power but lack formal control over creative spaces. Film, as a medium, operates in a liminal zone; it’s public culture but private enterprise, artistic expression but potential social influence. This makes it vulnerable to claims that it must respect boundaries it didn’t create and honour sensitivities it may not share.

The NFVCB’s responses to both controversies are telling. The board exists to balance creative freedom with social responsibility, guided by the National Film and Video Censors Board Act of 1993. That act empowers a Film Censorship Committee to examine content for psychological, sociological and moral impact. It requires that films have educational or entertainment value and promote Nigerian culture, unity or interest. It prohibits content that promotes ethnic prejudices or depicts extreme violence.

These are broad mandates, open to interpretation. But notice what’s absent: a requirement that films defer to religious institutions’ interpretations of their own symbols. The board is supposed to evaluate content within narrative and thematic context: exactly what it claimed to have done with A Very Dirty Christmas. Yet when religious pressure arrives, context collapses.

The NFVCB’s statement about Edo’s film acknowledged that the approval of the title was not intended to disparage or trivialise the Christian faith and was considered part of a fictional and creative expression. In other words, the board did its job correctly. But then comes the pivot: however, the board recognises that public perception and reception are critical elements of effective regulation.

This is where soft censorship lives—in the gap between professional evaluation and public perception. The board didn’t ban the film outright (hard censorship). Instead, it requested modifications and invoked responsiveness and dialogue. It frames accommodation as civic responsibility, and the filmmaker is encouraged, not forced, to comply. But the encouragement carries weight: the threat of withdrawal, the loss of commercial viability, the taint of religious insensitivity.

This regulatory tilt has consequences. It establishes that a religious offence or the potential for it carries special weight in content evaluation. Not legal harm. Not factual inaccuracy. But the possibility that faith communities might object. It incentivises religious groups to object early and loudly, knowing that the NFVCB will respond. And it teaches filmmakers that navigating faith sensitivities matters more than engaging with actual censorship criteria.

Nigerian cinema regularly depicts violence, corruption, infidelity, fraud, and various forms of social decay. These themes are considered fair game for dramatic exploration, even when they reflect badly on Nigerian society. Films about political corruption rarely see politiciansʼ groups demanding bans. Works depicting police brutality don’t get pulled because law enforcement objects. But touch religious symbols, even tangentially, even in the service of a story about something else entirely, and the machinery activates. This disparity reveals what’s actually being protected. It’s not social harmony in general. It’s specifically religious authority over religious representation.

The expectation that Nigerian cinema must be respectful, uplifting, and morally instructive has long shaped critical and popular discourse. Offence is often framed as artistic failure rather than as a possible byproduct of challenging representation. Yet, global cinema routinely interrogates sacred symbols, holidays, and religious iconography through satire, subversion, and dark humour. Nigerian cinema’s constraint is not a lack of such impulses, but a public culture that places heavy moral burdens on representation.

Christianity itself is built on narratives of imperfection, sin, and redemption. A film about messy family dynamics during Christmas aligns, in many ways, with Christian theological themes. The discomfort, therefore, may be less theological and more cultural: a resistance to seeing sacred seasons reflected as socially messy rather than symbolically pristine.

Every time a filmmaker modifies their work in response to symbolic objections rather than content concerns, something is lost. First, there’s the narrowing of imaginative space. If certain symbols become too risky to engage, filmmakers avoid them. Not because they have nothing meaningful to say, but because the commercial and social risks outweigh potential artistic gains. This creates zones of silence: subjects that should be available for creative exploration but become effectively off-limits.

Second, there’s the infantilisation of audiences. The logic of symbolic policing assumes viewers can’t distinguish between depiction and endorsement, between fiction and reality, between critical engagement and mockery. It treats Nigerian audiences as perpetually vulnerable to being misled by images, incapable of contextual interpretation. This is patronising and ultimately corrosive to cultural sophistication.

Third, there’s the empowerment of bad-faith readings. When you can condemn a work based on a title alone, without engaging its actual content or intentions, you incentivise superficial outrage. It becomes easier to police surfaces than engage with substance. This rewards those who are quickest to claim offense and punishes those who assume good faith interpretation.

There’s also the economic precarity it creates. Nigerian filmmakers operate in a challenging commercial environment with limited funding, short production cycles, and narrow profit margins. Adding religious approval (informal but necessary) to the list of hurdles makes filmmaking riskier and more expensive. It particularly affects independent producers who can’t afford the buffer that major production companies might have.

Finally, there’s the question of cultural maturity. A vibrant film culture requires the ability to explore difficult terrain, ask uncomfortable questions, and risk offense in pursuit of insight. If the price of avoiding religious tension is artistic timidity, Nigerian cinema will struggle to achieve the cultural depth and international recognition its practitioners seek.

The battles over A Very Dirty Christmas and the yet-to-be-released Blood Brothers might seem small in the grand scheme of things, but they’re symptoms of a larger struggle over who controls cultural meaning in Nigeria’s public sphere.

Religious institutions have legitimate interests in how faith is represented. But so do artists, who need creative freedom to explore the complex realities of modern life. So do audiences, who deserve access to diverse perspectives. And so does Nigerian culture as a whole, which benefits from robust creative discourse, even when it’s uncomfortable.

The pattern of symbolic policing—reacting to surfaces, pressuring regulators, forcing modifications—represents an attempt to extend religious authority into creative spaces through informal mechanisms when formal ones don’t exist. It works because it exploits the NFVCB’s dual mandate: support creativity while preventing social harm. Religious groups frame symbolic offense as potential social harm, forcing the board to choose between artistic freedom and social peace.

But this framing is false. Social peace doesn’t require artistic homogeneity or religious veto power over creative expression. It requires exactly what both controversies lacked: the ability to engage with difficult representations without immediately mobilising for censorship. It requires religious communities confident enough to allow artists to explore faith’s complexities. It requires regulators willing to defend their own professional judgments.

Most fundamentally, it requires recognising that in a plural society, no group owns meaning absolutely. Christmas is sacred to Christians, but it’s also a cultural phenomenon that artists can explore from multiple angles. The niqab is a religious garment, but it’s also clothing that exists in the world and sometimes appears in contexts its wearers wouldn’t choose. These truths can coexist. Fiction can engage religious symbols without mocking the faithful. Metaphors can be provocative without being blasphemous.

The cost of refusing this complexity is a cinema that plays it safe, avoids depth, and ultimately fails to capture the full texture of Nigerian life. Because Nigerian life isn’t just pious Muslims and devout Christians living separate existences. It’s messy family reunions at Christmas. It’s the reality that criminals sometimes exploit religious attire. It’s the friction between appearance and truth, between sacred seasons and human imperfection.

That’s the story Ini Edo wanted to tell. Whether her title was artistically wise is debatable. Whether she should have had to defend it through tears, pledging her Christian faith and begging not to lose her investors’ money, is not. The machinery that put her in that position—the reflexive outrage, the regulatory deference, the commercial vulnerability—is the real problem. Until it changes, Nigerian cinema will keep bumping against invisible boundaries, learning through painful experience what cannot be said, shown, or even titled.

The question hanging over these controversies isn’t ultimately about one Christmas film or one niqab image. It’s about whether Nigerian cinema can mature into a space where difficult representations are possible, where artists take risks without facing commercial annihilation, and where religious institutions trust their faithful enough to let them engage with complexity. Right now, the answer seems to be: not yet. But the conversation has at least begun.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big