Jazz Infernal is a compact but resonant meditation on grief, migration, and the pressure to become someone else’s dream.

By Joseph Jonathan

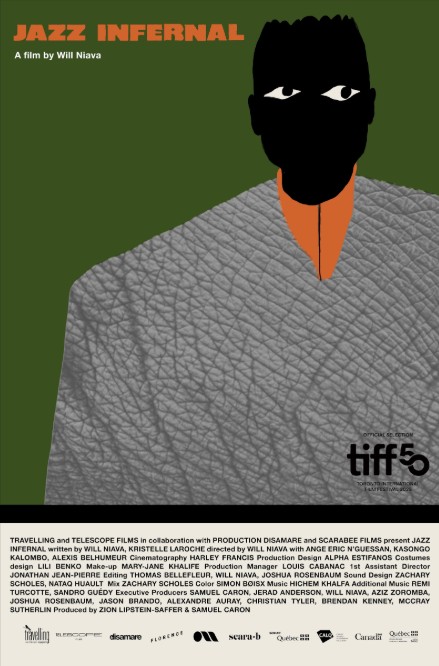

At Sundance 2026, Jazz Infernal announced itself as a film more interested in feeling its subject than explaining it. Directed by Canadian-Ivorian filmmaker Will Niava, the short film situates itself at the intersection of grief, migration, and inheritance, using jazz not merely as a backdrop but as an emotional language through which its protagonist learns to articulate himself. In an era where stories of the African diaspora are often flattened into either trauma or triumph, Jazz Infernal occupies the uneasy space in between: where identity is negotiated, not resolved.

Co-written by Niava and Kristelle Laroche, the film follows Koffi, the son of a celebrated Ivorian trumpet player, who arrives in Montreal, Canada carrying both the weight of his father’s reputation and the unprocessed grief of his death. He is a young musician who, in a cruel irony, finds himself unable to play until he confronts what his father’s music—and absence—means to him. Niava frames this paralysis as more than a personal block; it becomes a metaphor for the broader immigrant experience, where the past looms loudly even as the present demands reinvention.

Montreal in Jazz Infernal is not the postcard city of festivals and cafés but a sensory overload for a newcomer still trying to decode its rhythms. Jazz Infernal captures Koffi’s first day with a jittery, almost breathless energy, translating the disorientation of arrival into form. The editing is restless, the zooms intrusive and expressive, mirroring the improvisational chaos of jazz itself. Rather than smoothing the immigrant experience into a digestible montage, the film embraces its messiness. Displacement here is not just geographic; it is psychological, cultural, and sonic.

Ivorian actor Ange-Eric Nguessan anchors the film with a performance that resists easy sentimentality. His Koffi is withdrawn but not inert, visibly torn between reverence and resentment toward a father whose shadow feels inescapable. Nguessan conveys this tension in quiet gestures; the hesitation before lifting the trumpet, the way his eyes search for something familiar in an unfamiliar city. He plays Koffi as someone caught between inheritance and invention, embodying a question that haunts many children of diaspora: how much of your parents’ story is destiny, and how much is burden?

Jazz, in Niava’s hands, becomes both inheritance and liberation. The music never fades into the background; it pulses through the film, shaping mood, pacing, and meaning. Sound becomes grief made audible, but also the possibility of communion. When Koffi connects with a local jazz band, the film finds its emotional pivot, not in assimilation, but in improvisation, in the act of finding belonging through shared sound rather than shared origin. Jazz Infernal suggests that diaspora identity is less about preservation and more about remixing, less archive and more improvisation.

What makes the film quietly radical is its refusal to resolve these tensions neatly. The final turn lands with an unsettling ambiguity, raising the uncomfortable idea that not every child is meant to continue their parents’ legacy, and that reverence can be its own kind of trap. Jazz Infernal resists the sentimental arc that would frame inheritance as destiny, instead lingering on the psychic weight of expectation; the way love, memory, and duty can curdle into constraint. Niava’s film suggests that legacy is not only something passed down but something imposed, and that choosing not to inherit can be as emotionally charged as choosing to carry on.

In a cultural moment obsessed with lineage and legacy-building, Jazz Infernal dares to ask whether inheritance is always a gift or sometimes a haunting. This question resonates deeply within African and diasporic contexts, where ancestry is often framed as sacred, continuity is moralised, and deviation from lineage can feel like betrayal.

Across many African cultures, the child is imagined as a vessel of ancestral continuation, tasked with carrying names, professions, reputations, and unfinished dreams forward. By troubling this logic, Jazz Infernal quietly pushes against a foundational cultural script: that to honour the past is to reproduce it. Instead, the film gestures toward a more uncomfortable, but perhaps more honest, truth: that sometimes the most respectful act is not continuation, but refusal, reimagining, or rupture.

Visually, the film is striking. The cinematography by Harley Francis gives emotional texture to Koffi’s confusion and wonder, capturing Montreal as both alienating and magnetic. The camera lingers on faces, instruments, cityscapes, and fleeting encounters, turning Koffi’s first day into a collage of sensations. The craft is confident without being showy; every stylistic choice feels in conversation with the music, creating a film that moves like a jazz composition: structured, but alive with improvisation.

Ultimately, Jazz Infernal is a compact but resonant meditation on grief, migration, and the pressure to become someone else’s dream. Niava’s film doesn’t offer catharsis so much as a process: mourning as a prerequisite to creation, disorientation as a step toward belonging. In its brief runtime, it captures a truth that many diaspora narratives miss: that identity is not inherited, fully formed, but composed, note by note, in the spaces between memory and motion.

*Jazz Infernal premièred at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival. It screened as part of the short film program at the 2026 Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Short Film Jury Award: International Fiction.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big