Alive Till Dawn is competent enough to be watchable, ambitious enough to signal intent, but ultimately too cautious to be genuinely transformative.

By Joseph Jonathan

When Uzor Arukwe—one of Nollywoodʼs most bankable leading men—stepped behind the camera to co-produce Alive Till Dawn, he wasnʼt just making a zombie film. He was making a bet on genre as a viable commercial territory and on his own star power as sufficient collateral to greenlight a project that studios might otherwise consider too niche.

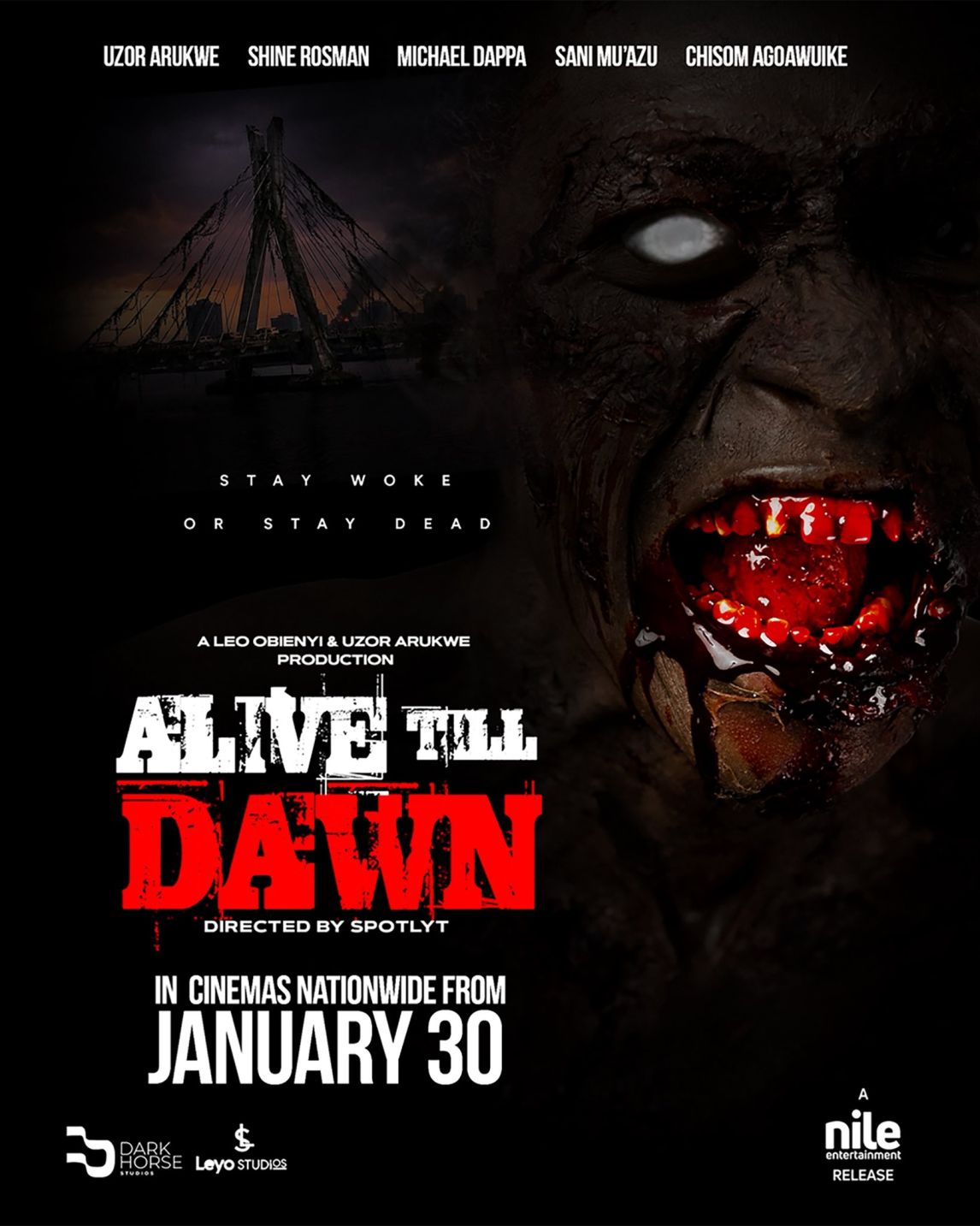

Released in Nigerian cinemas on January 30, 2026, this zombie thriller directed by Sulaiman Ogegbe arrives at a curious moment in the industry: one where actors are increasingly leveraging their visibility to bypass traditional gatekeeping, and where “innovation” has become a marketing imperative even when the product itself remains formally conservative.

Alive Till Dawn bills itself as “Nigeriaʼs first zombie apocalypse film”, a claim that requires immediate scrutiny. C.J. “Fiery” Obasi’s Ojuju (2014)—a zero-budget, DIY zombie film set in Lagos slums—exists as an incontrovertible precedent. But Ojuju was made outside the mainstream apparatus, circulated primarily through festival circuits, and never received a theatrical release.

In Nollywoodʼs calculus, if a film doesnʼt play in multiplexes or stream on a major platform, it can be erased from the official record. The “first” designation, then, is less about chronological accuracy and more about market positioning: Alive Till Dawn is the first zombie film “that counts”—the first with proper distribution, recognisable stars, and the institutional backing to be legible as a Nollywood product rather than an auteurist curiosity.

This tells us something essential about how the industry understands genre experimentation. Itʼs not enough to do something; you must do it within established commercial frameworks for it to register as innovation.

Obasi’s film was too marginal, too aesthetically unruly, too embedded in the lived textures of informal settlements to be claimed by an industry increasingly oriented toward middle-class respectability and platform-ready packaging. Alive Till Dawn, by contrast, arrives with the polish and narrative conventions that make it legible to both domestic multiplexes and international streaming buyers. It ʼs genre filmmaking as risk mitigation, not radical departure.

The Actor-Producer as Industrial Symptom

Arukwe’s pivot into production mirrors a broader trend Afrocritik had earlier identified in a recent essay on Africa’s film industry in 2026: popular actors using their leverage to produce projects that reflect their creative ambitions or market instincts.

This isnʼt vanity producing in the traditional sense; it’s actors recognising that their star power can function as pre-sold IP in a crowded marketplace. When an actor like Arukwe attaches himself to a zombie film, heʼs signaling to distributors and platforms that the project has built-in audience appeal, even if the genre itself remains unproven in Nollywood.

But there’s a tension here. Arukwe chose a relatively unproven genre for his producing debut, not prestige drama or romantic comedy, the safer commercial bets. This suggests either genuine creative curiosity or, more cynically, an understanding that platforms are hungry for “local genre content” that can be marketed as both culturally specific and globally familiar.

Zombie films travel well internationally; they require minimal cultural translation. A Nigerian zombie apocalypse offers the exoticism of a setting without demanding that international viewers do interpretive labour around unfamiliar narrative conventions or spiritual cosmologies.

Yet, this outward-facing orientation comes at a cost. Alive Till Dawn borrows heavily from Western zombie cinema—the siege narrative, the slow-moving undead, the interpersonal conflicts within a survivor group—without meaningfully adapting those conventions to Nigerian social realities.

The film opens with a pointed political gesture: workers dump hazardous waste into a water body, followed by an intertitle citing UNICEF data on child mortality from water-related illness. Itʼs a direct invocation of infrastructural failure, environmental violence, and state neglect. But having made that gesture, the film immediately retreats into individualised melodrama, centring the daughter of a police officer rather than the communities directly devastated by pollution.

Rather than sustain a broad sociopolitical critique, it confines itself largely to a police station siege narrative centred on Alex (Sunshine Rosman), the daughter of a high-ranking officer. The apocalypse becomes intimate rather than collective, filtered through insulated figures rather than those most vulnerable to environmental catastrophe. The polluted water that inaugurates the crisis becomes a backstory rather than an ongoing indictment. What begins as systemic horror narrows into personal survival melodrama.

This narrowing is revealing. Nollywood often gestures toward critique but hesitates before fully implicating power. By situating the primary perspective within state-aligned characters, the film inadvertently softens its own political charge. The police station, ostensibly a fortress against chaos, becomes a metaphorical bunker in which institutional authority attempts to reassert coherence. The undead outside threaten collapse; inside, hierarchy persists. In this dynamic, the zombie ceases to be an embodiment of infrastructural injustice and becomes merely an external antagonist.

This is where the film’s politics collapse. Obasi’s Ojuju, for all its technical limitations, sustained its social critique by keeping the narrative grounded in the slums; among the people whose lives are shaped daily by systemic abandonment.

Alive Till Dawn invokes that context but cannot commit to it, instead foregrounding law enforcement and middle-class protagonists. The apocalypse becomes the backdrop; the “everyman” becomes scenery. Itʼs a form of narrative gentrification, where working-class suffering is acknowledged just long enough to generate moral urgency, then displaced by the survival struggles of those insulated by power.

Genre Memory and the Horror Label

The film’s marketing as Nigeria’s “first” also raises questions about Nollywood’s relationship to its own archive. Nigerian horror has deep roots—Living in Bondage (1992), Nneka the Pretty Serpent (1994), Karishika (1998), End of the Wicked (1999)—films that terrorised a generation of viewers through their engagement with occult economies, spiritual warfare, and ritual violence.

These films werenʼt commonly called “horror” in public discourse; they were “spiritual/supernatural films” or simply “Nollywood classics”. The horror label, in Nigerian popular imagination, is reserved for Western monster movies—Freddy Krueger, zombies, vampires—not the culturally embedded terrors of blood money rituals and ancestral curses.

This distinction matters because it reveals what gets archived and what gets erased. Alive Till Dawn positions itself within a lineage of Western horror, not Nigerian spiritual cinema, even though the latter has proven far more effective at generating genuine fear among local audiences.

By adopting zombie iconography wholesale—without the kind of cultural translation that might make the undead resonate with Nigerian cosmologies of death, possession, or spiritual contamination—the film risks becoming a derivative spectacle. It borrows the form but not the function.

Audience responses bear this out. During my screening of the film at the cinema, laughter often greeted moments meant to be terrifying. A couple close to me kept referencing how the film felt more American than Nigerian at times, a suggestion which captures the disconnect.

Western horror conventions donʼt reliably translate into fear for Nigerian audiences because the threats feel imported, abstract, disconnected from lived spiritual and social anxieties. The zombies in Alive Till Dawn are CGI monsters; they don’t carry the existential dread of, say, a mermaid spirit demanding blood sacrifice in exchange for wealth. They’re intellectually understood as threats but not viscerally felt as danger.

What Zombie Narratives Could Mean

The zombie is a globally circulating figure. Its genealogy runs through Haitian folklore, American Cold War allegory, and twenty-first-century contagion narratives. In contemporary cinema, it has become shorthand for systemic collapse. Zombie films, historically, have been among cinema’s most politically legible genres.

George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) was inseparable from Civil Rights-era America; Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002) metabolised post-9/11 anxieties about contagion and social collapse; South Korea’s Train to Busan (2016) allegorised class stratification and neoliberal abandonment. The zombie, as a figure, embodies systemic breakdown; the moment when social contracts dissolve, when the state can no longer guarantee safety, when survival becomes atomised and Darwinian.

Nigeria in 2026 offers fertile ground for such allegories. Economic precarity, state failure, infrastructural rot, environmental catastrophe—these arenʼt speculative futures but present conditions. A zombie narrative set in Nigeria could be a devastating political document, a way of externalising the sense that institutions themselves are undead: still moving, still claiming authority, but fundamentally hollow, incapable of protecting the living.

Alive Till Dawn gestures toward this potential but cannot sustain it. The film’s zombies are caused by water pollution—a clear nod to real crises—but the narrative doesn’t follow through on that premise. It doesn’t interrogate who profits from pollution, who bears its costs, or what it means when the state’s primary response to a crisis is militarised containment rather than remediation. Instead, the film defaults to a survival thriller template where the apocalypse is atmosphere, not argument.

Technical Competence, Narrative Incoherence

To its credit, Alive Till Dawn demonstrates visual competence within genre conventions. The cinematography employs shadowy lighting and a roving, predatory camera that mimics the zombies’ lurching movement. Sound design—eerie moans, realistic gunfire, a score blending Nigerian percussion with synth tension—creates moments of genuine atmosphere.

The production values are noticeably higher than Ojujuʼs guerrilla aesthetic, which is both an achievement and a limitation. The polish signals Nollywoodʼs growing technical capacity but also its increasing risk-aversion. Genre experimentation here means adopting genre trappings, not reinventing genre grammar.

The performances are uneven. Sunshine Rosman, playing Alex, carries the filmʼs emotional weight with determination, embodying fear and resilience even as the script burdens her with contrived misfortunes. Michael Dappaʼs Isaac—a hyper-dramatic ex-prisoner who becomes Alexʼs ally—brings passion but veers into melodrama. Arukweʼs Badu, meant to be a domineering antagonist, is sabotaged by his own performance: exaggerated delivery and constant shouting render him more comical than menacing, deflating scenes that require genuine threat.

The screenplayʼs problems run deeper than individual performances. Dialogue oscillates awkwardly between pidgin and polished English, breaking character consistency. Early scenes establish the ex-convicts as speaking pidgin, signalling class and education levels, but this distinction collapses as the film progresses and everyone begins speaking in fluent, accent-neutral English. The inconsistency suggests the filmmakers couldnʼt decide whether to ground the story in recognisable Nigerian speech patterns or default to a more “universal” (read: Westernised) idiom.

More troubling is the filmʼs characterisation. The survivors are archetypal rather than dimensional—the strong leader, the loyal sidekick, the damsel. No one undergoes a meaningful transformation. They exist to advance plot mechanics, not to embody complex human responses to catastrophic stress. In a genre that depends on viewers caring whether characters survive, this emotional flatness is fatal.

The Illusion of “Innovation”

Ultimately, Alive Till Dawn functions as what we might call aspirational genre cinema: it wants credit for attempting something new without fully committing to the formal, narrative, or political possibilities that newness might entail. Itʼs innovation as a branding exercise rather than a creative rupture.

This is symptomatic of a larger pattern in contemporary Nollywood, where “firsts” are declared with increasing frequency as if novelty alone constitutes achievement. But genre isnʼt just iconography. Itʼs a set of narrative structures, thematic preoccupations, and audience expectations that must be engaged seriously, not merely appropriated as marketing hooks.

The irony is that Nollywood already possesses a robust tradition of speculative and horror cinema; it simply doesnʼt necessarily recognise it as such because it emerged from video-era aesthetics and spiritual rather than secular frameworks. Living in Bondage is a horror film. Sakobi: The Snake Girl (1998) is a monster movie. But because these films donʼt conform to Western genre taxonomies, they’re not claimed as precedents when new “firsts” are announced.

What Alive Till Dawn represents, then, is less a creative breakthrough than an industrial realignment: the absorption of genre filmmaking into Nollywoodʼs mainstream apparatus, but on terms that prioritise marketability over formal experimentation. Itʼs genre cinema designed for platform distribution, for the kind of cultural capital that comes from being seen as innovating even when the innovations are skin-deep.

What Comes Next?

If Alive Till Dawn succeeds commercially—and early box office reports suggest modest performance—it may create space for more genre experiments. But success will likely be measured in narrow terms: Did it recoup its budget? Did it secure a streaming deal after its theatrical run? Did it generate enough buzz to justify similar projects? These are legitimate industry concerns, but they donʼt necessarily lead to better, more ambitious filmmaking.

The films I want to see emerge from this moment arenʼt zombie movies that mimic Western templates. I want horror that engages seriously with Nigerian cosmologies of spiritual power, possession, and the permeable boundaries between living and dead. I want dystopian narratives that donʼt just borrow apocalypse aesthetics but actually reckon with the specific ways Nigerian state failure manifests. I want speculative cinema that metabolises Afrofuturism into something concrete and rooted rather than abstract and aspirational.

Alive Till Dawn doesn’t deliver that. But its existence—its funding, its production, its release—tells us where Nollywood is right now: caught between the desire to be seen as formally innovative and the unwillingness to abandon commercially safe templates. Arukwe’s decision to produce a zombie film is indicative of this contradiction. He chose genre, but genre-lite. He invoked social crisis, but defaulted to individualised melodrama.

The film is competent enough to be watchable, ambitious enough to signal intent, but ultimately too cautious to be genuinely transformative. Itʼs a symptom of Nollywood’s genre turn, not its fulfilment—a placeholder in a conversation thatʼs just beginning, a trial balloon testing whether audiences and platforms will reward formal experimentation or simply demand more of the same with different packaging.

For now, the answer seems to be the latter. But the conversation itself—about what genre can do, what it should mean, and how it might articulate specifically Nigerian anxieties and imaginaries—remains urgent and unresolved. Alive Till Dawn is one attempt at an answer. It wonʼt be the last.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big