Worse Than Fire feels like walking through Maiduguri after the water has dried. The air still carries the smell of silt, but there are children playing again, rebuilding games from broken sticks.

By Joemario Umana

With dedication to Shalom Soji-Oderinde and Dr Amali Joshua

There’s a line from the 2025 anime, To Be Hero X, that stuck with me and reminded me of what the authors of Worse Than Fire did with their book: “The most powerful opposite of violence is imagination”.

In the context of that anime, the line was an act of an attempt to reclaim what humanity had lost to cruelty. But in Worse Than Fire, co-authored by Dr. Amali Joshua and Shalom Soji-Oderinde, imagination is not a form of escape; it is rather an instrument of witness. It is the beacon that holds the memory of water.

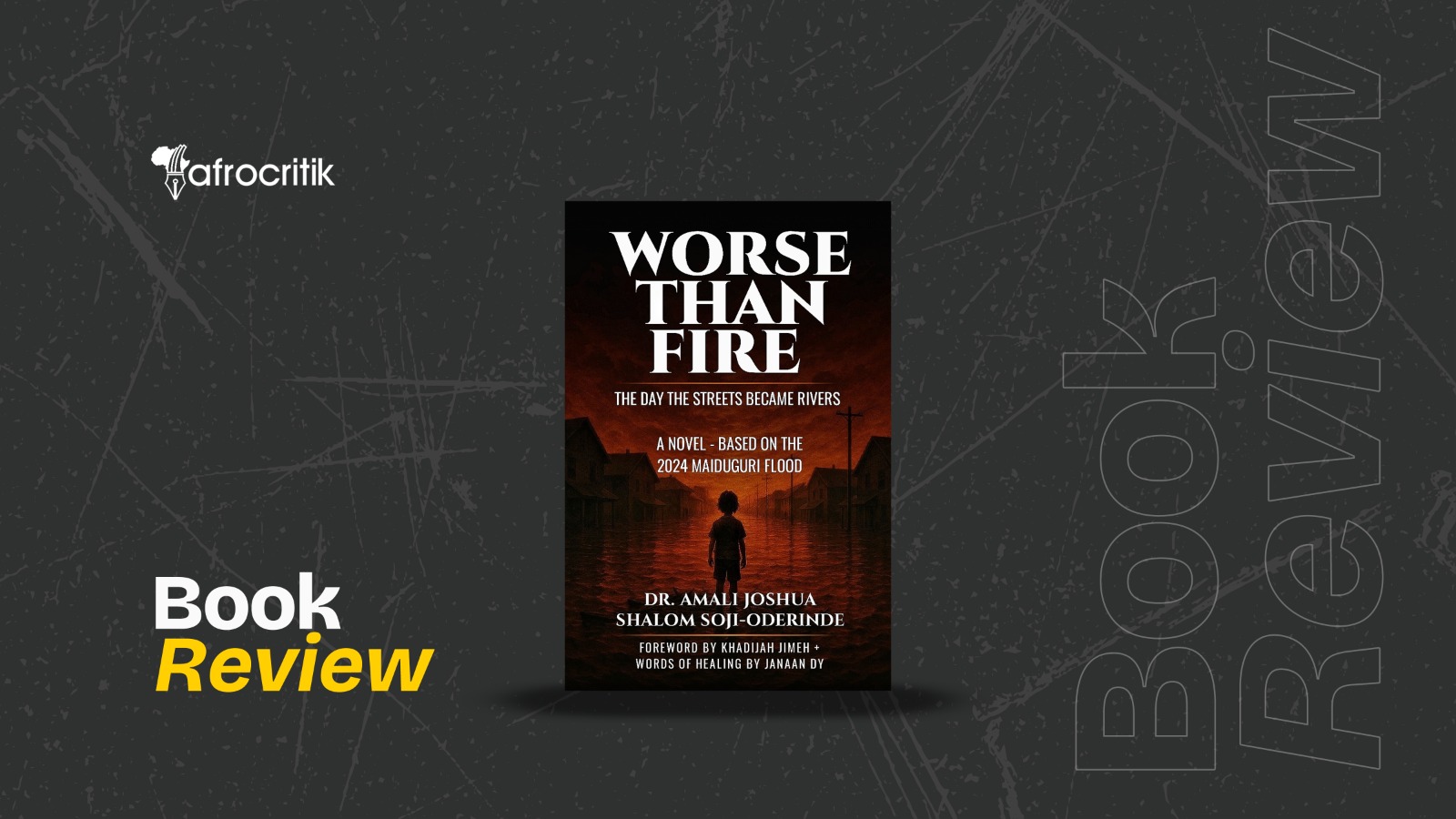

Set against the 2024 Maiduguri flood, a disaster that submerged the city into a belly of water, Worse Than Fire reclaims the story of survival from the margins. Its full title, Worse Than Fire: The Day the Streets Became Rivers, suggests something close to biblical, a kind of elemental reckoning, a city’s baptism by loss. But the writers do not mythologise the flood; they render it in the grain of lived life as in soaked mattresses, collapsed walls, bodies carried off by currents. It is a documentary, but it is also intimate. The prose reads like someone trying to speak through a mouth still filled with water.

The city of Maiduguri has lived with violence for more than a decade, ranging from insurgency to displacement, from the smoke of bombs to the quiet ache of loss. The flood came as another kind of war. The authors capture this continuity in a chilling line from their “Notes from the Authors”: “This city has faced terror attacks and recent fire outbreaks; yet, it did not flinch and stood strong. But something worse than fire was lurking just beyond its borders”.

That phrase, worse than fire, carries both literal and moral weight. Fire is visible, spectacular; it burns and ends. But water, slow, encroaching, and indiscriminating, erases. It takes away the shape of things and leaves behind silence. The writers understand this difference intuitively. Their retelling of the Maiduguri flood is, therefore, not just reportage. It is an act of recovery.

Throughout the book, the flood is seen not as a metaphor but as a catastrophe, one that collapses social, religious, and economic boundaries. “The flood did not discriminate. E touch everybody, literally,” one of the narrators writes. What makes this line powerful is its insistence on the local rhythm of grief, that is, the mix of English and Nigerian pidgin carrying both resignation and dark humor. The book’s realism is built on that kind of linguistic intimacy: the floodwaters do not wash away the people’s voice; they deepen it.

Carrying on, Worse Than Fire is structured as a polyphonic narrative, that is, alternating between documentary storytelling, journal entries, eyewitness testaments, and community reportage. This form mirrors how disasters are remembered in real life: not through a single authority but through fragments, conversations, rumors, and retellings.

From the opening story, “Home is Where the Heart Is”, we are ushered into a living city with its markets, bridges, and daily rhythms before the water arrives. The detail is slow and generous, it allows the reader to care. So, when the flood comes, and the narrator wakes to find his feet in “something cold and wet”, the reader feels implicated.

The voice moves between first-person panic and collective reflection: “We started by putting important things in small bags and placing other stuff on elevated surfaces”. The ordinariness of that sentence, its domestic cadence, is what makes it heartbreaking.

There’s also a deliberate choice in tone. The prose refuses melodrama. Instead, it offers tenderness, humour, and clarity—a kind of humane realism. In “Becoming Refugees,” the narrator reflects: “Funny how the people in the villages we once called were calling us in the city.” That reversal of privilege and geography captures the dislocation of the flood more effectively than any statistic could.

The book’s most affecting chapter is “From Khadijah’s Journal”, a chapter that introduces a real survivor’s account. Khadijah, a student and humanitarian worker, narrates her escape from the flood in vivid, unflinching detail, from the moment water “leaked through a small hole” to sleeping under trees and fuel stations. Her story transforms the book’s tone from reportage to testimony.

What’s remarkable is how she turns the lens on herself as both subject and observer. Having worked in humanitarian spaces, she reflects on the ethics of representation: “During this flood, someone took a photo of me and my family and posted it online. That moment made me realise just how exposed people feel in their lowest moments”.

This reflection is what separates Worse Than Fire from many disaster chronicles. It is self-aware, uneasy with voyeurism. It understands that writing about suffering can easily turn into aestheticising it. Instead, it insists on dignity for both the victims and of the act of witnessing itself.

In a chapter titled “The Humanitarians Need a Humanitarian”, the authors make a similar argument, dramatised through an incident where one aid organisation rescues another from floodwaters. The scene, simple yet profound, inverts the savior narrative: those who rescue must also learn to be rescued. It’s one of the book’s most powerful moral statements—that empathy is not hierarchical but circular.

Both writers come from medical and scientific backgrounds—Dr Amali Joshua being a physician, and Shalom Soji-Oderinde a medical student—and this perspective shapes how they render the city as a body under observation. The flood becomes almost pathological: the streets are “veins” swollen with water; the hospitals are “infected”.

In the chapter, “Water Borne”, the language shifts into diagnostic precision, detailing cholera outbreaks, malaria surges, and mental health crises. Yet, the clinical eye never numbs the human heart. Instead, it exposes how fragile health systems mirror a nation’s deeper vulnerability.

Still, the book doesn’t stop at science. It turns toward faith and spiritual endurance. The “Words of Healing” section by Janaan DY is a soft hymn addressed to survivors, urging patience and self-love. “Be patient with yourself and how long it’s taking you to heal,” she writes. “You’ll remember how you survived”. The text reads like collective therapy, a communal liturgy of recovery. In a nation where trauma is often silenced by stoicism, this insistence on emotional care is radical.

Circling back to that To Be Hero X line—imagination as the opposite of violence—it becomes clear that Worse Than Fire uses storytelling itself as reconstruction. The writers build again what the flood nearly or did destroy: memory, empathy, belonging. Imagination here doesn’t deny reality; it restores it.

In the epilogue, the authors write: “The flood came and left, but it didn’t really go. It stayed in broken walls, in missing things, in the soft silence that now followed laughter. But it also left something behind… The city changed… And late at night, when the city was quiet, the wind still whispered strange things.”

That final image—wind whispering through a wounded city—is where literature and life meet. It’s the moment where reportage becomes elegy. And perhaps that’s what makes Worse Than Fire so necessary: it reminds us that survival isn’t only about being alive; it’s about remaining human enough to tell the story afterward.

At its heart, Worse Than Fire is an argument for empathy as civic imagination. By situating the flood within Maiduguri’s broader history of insurgency, economic precarity, and climate neglect, it demands accountability without slipping into accusation. This is what I might love to refer to as the politics of empathy. The authors write with the steadiness of witnesses, not judges. Their restraint is political. It says: we will remember, but we will also rebuild.

In a country where state failure has made both insurgency and climate disaster routine, Worse Than Fire insists on remembering the ordinary lives within those statistics, which include the woman who shared her last bread, the boy who guarded an old widow’s home, the lovers who met while volunteering in an IDP camp. These small human gestures are the book’s moral architecture. They are, in essence, what imagination does: it makes space for tenderness in the ruins.

In conclusion, reading Worse Than Fire feels like walking through Maiduguri after the water has dried. The air still carries the smell of silt, but there are children playing again, rebuilding games from broken sticks. The flood was real—a fact of nature and of negligence—but the book refuses to let that reality end in despair. It transforms it into a collective memory, insisting that grief can be a form of civic imagination.

In the end, Worse Than Fire is more than a disaster narrative; it is a document of survival, a chronicle of how a city reclaims its story. Its authors—a doctor and a medical student—understand that healing is not only biological; it is narrative. Each page becomes a form of resuscitation.

And so, when the anime says “the most powerful opposite of violence is imagination”, I think of Maiduguri with the waters receding, its people standing again, still naming what they lost, still imagining what can be rebuilt. Because even when the streets become rivers, imagination remains the dry ground we stand on.

Joemario Umana, Swan XVII, is a Nigerian creative writer and a performance poet who considers himself a wildflower. His writings have appeared in journals like trampset, Strange Horizons, Isele Magazine, Afrocritik, LOLWE, Chestnut Review, Uncanny Magazine, Poetry Sango-Ota, South Florida Poetry Journal, Orange Blossom Review, Frontier Poetry, Prairie Schooner, Poetry Column-NND, Brittle Paper and elsewhere. He is also the poetry editor of Akpata Magazine. He has a published poetry pamphlet and a fiction chapbook to his name. He tweets@JoemarioU38615.