The influence of holistic theatre on Christopher’s Ojirami: The Weeping River is a delight. Scenes are momentarily paused to enact dances and demonstrative choreography, which adds to the overall dramatic experience.

By Afrocritik’s Editorial Board

It should not be remiss to declare that playwriting and drama have been in some decline in Nigeria in recent times, notwithstanding the efforts of organisations such as The Nigeria Prize for Literature, which awards $100,000 to a book of drama every four years. That effort is only one in a national literature that desperately needs a dramatic revival – at least on a scale close to what was witnessed in the heydays of Wole Soyinka.

Yet, the prospect of a holistic revival is admittedly quite difficult in a world that has become dominated by new dramatic forms orchestrated by technology and the rise of social media. Video clips have become the go-to for entertainment (never mind edification) for the vast majority of people, and traditional stage drama seems to manifest itself more and more as an elitist engagement.

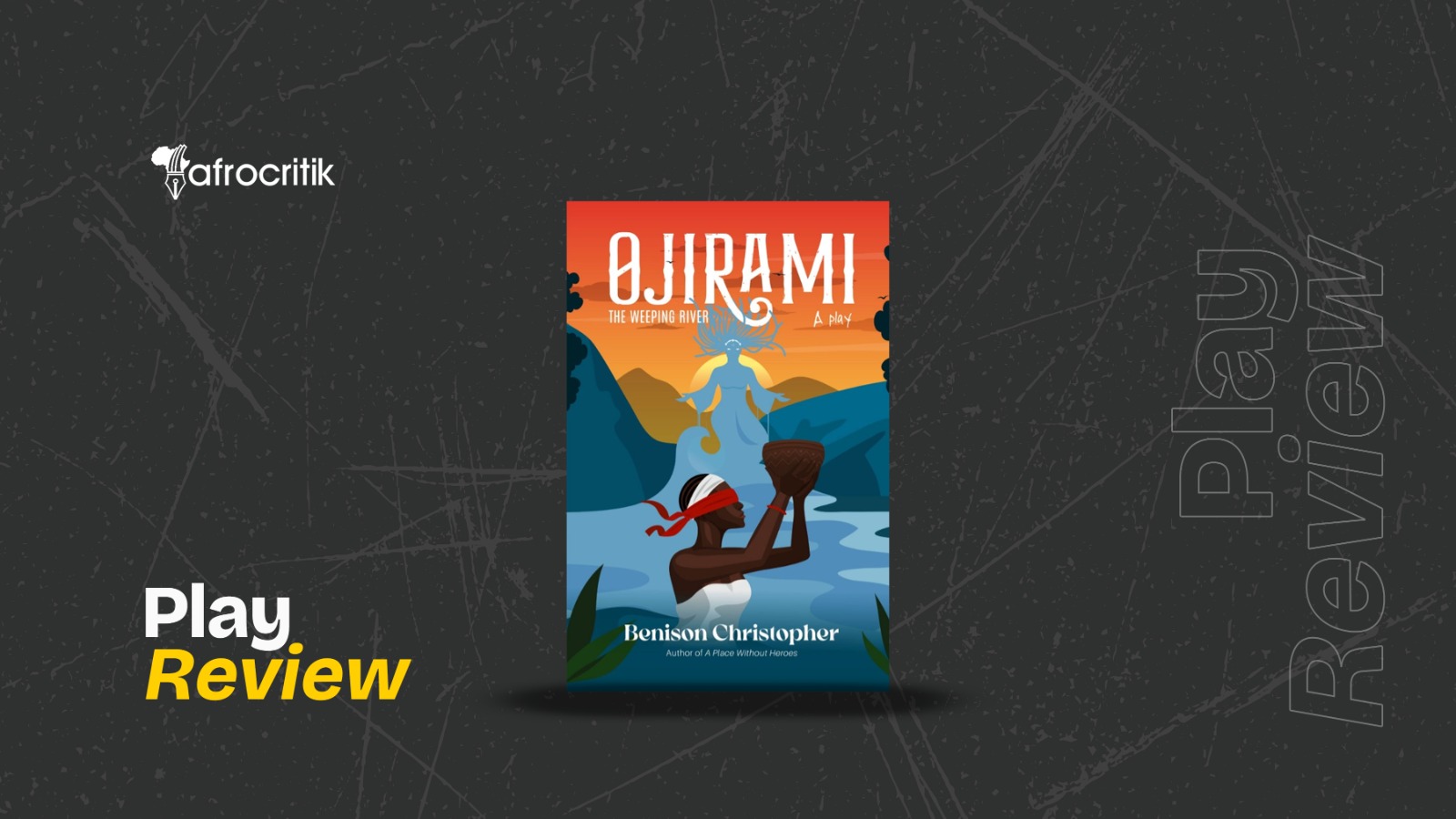

If drama, as we have known it, must progress, then Nigerian writer and playwright Benison Christopher’s new play, Ojirami: The Weeping River, can perhaps provide something of a subtle blueprint for that. Taking the legend of Ojirami River (in Edo State) as its starting point, Christopher weaves a tale that conflates tragedy, myth, and modernity into a straightforward plot involving Ojirami village.

In the play, Ojirami is both the name of the village, the River, and the deity that dwells in its liquid depths. This tripartite connection between location, geography, and spirituality holds a strong influence on the village. Very early on in the play, we understand that the lives of the people are ruled by their reverence for the Ojirami River and its deity, Ojirami. The first scene, in which the Ojirami priest (who is automatically the village priest), Elder Afekhafe, performs the village annual cleansing, is clearly reminiscent of Ezeulu in Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God (1964).

Like Achebe’s Umuofia, in Christoper’s play, the Ojirami villagers’ strong belief in the efficacy of the deity cuts across all their life’s endeavours, from farming to marriage to childbirth. Childbirth and marriage, particularly, are central to the disruption of the equilibrium created by the villagers and the deity.

Ekpen, the main character of concern here, is an IJGB (I just got back) returnee from the UK, who, after just two years away from Ojirami, returns with all sorts of foolish and ridiculous affectations about how the village is “bush” and “uncivilised” while the UK is supposedly the epitome of modern refinement. Along with his friend and sidekick, Ofei, Ekpen roams the village in winter coats under the intense heat of the African sun, claiming that everything in the village is beneath him. Well, except for a beautiful young woman named Ureshemi, a nurse whom he plans to deceive into marriage with him, so she can come to the UK with him and not only earn the good salaries nurses earn over there but also give him most of it.

At one point, the character of Ekpen becomes so ridiculous that it can only be related to in terms of farce. His intense and undiagnosed self-hate and an inferiority complex define his every move. But Ekpen is not the only stock character here. Many of Christopher’s characters can certainly be described in terms of moral stereotypes: Ekpen personifies selfishness and other similar negative virtues, Ofei is foolishness; Omomije (the priest’s acolyte) is purity and forthrightness; Ureshemi is beauty and peace, and so on.

Each virtue, positive or negative, appears to do something in the plot. For instance, we realise later on in the play that Ekpen’s father, Eshioza, had committed a wrong which foreshadowed some of the later events involving his son.

There is so much going on here, particularly the topicality of Nigerian immigration in the UK. It seems as though the playwright has listened carefully to all the conversations and trends emanating from those cycles: men malicious marrying or intending to marry nurses from Nigeria because they earn good money, dating those who marry white women while still attempting to marry Nigerian girls in Nigeria, those who assimilate and never return, those who have to make careers out of traditional and nontraditional professions, etc.

The conflict of the play involves, on one hand, Ekpen’s attempt to convince his father to sell another of his lands so he can sponsor him to return to the UK (where he’s secretly making failing grades in school); on the other hand, it is his attempts to woo Ureshemi into marriage with him. When the plan backfires, and he attempts to rape her, the village is suddenly thrown into grave spiritual terror whose repercussions Eshioza and his family pay bitterly for.

The river goddess’s actions in the play’s central conflict are a feminist conceit in the hands of the dramatist. Christopher has clearly chosen to make the excesses of foolish men a focus of mythical retributive justice, which works rather well for the play’s purposes. The play’s other great strength is humour.

Many of those moments occur with Ekpen trying to enforce a fake attunement to British life on Ojirami culture; the clash created by his exertions is extremely ludicrous. One such farcical moment occurs in many scenes where Ekpen facetiously rejects Nigerian food in favour of “British food” which his mother obviously cannot prepare (even while he, on one occasion, finishes a big plate of soup and swallows that Ureshemi brings him).

The influence of holistic theatre on Christopher’s dramaturgy is a delight. Scenes are momentarily paused to enact dances and demonstrative choreography, which adds to the overall dramatic experience. The play’s magic realism is performed as part of many dramatic set pieces, complete with soliloquies, dance, and prop devices.

At the same time, Christopher has, to an appreciable extent, married the topicality of Nigerian immigration trends on social media with an age-old river myth. The result is an interesting drama of what it means to navigate the demands of our times while still maintaining a respect for the traditions and cultural practices that define the places where we originate from.

Chimezie Chika is a staff writer at Afrocritik. His short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Weganda Review, The Republic, The Iowa Review, Terrain.org, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Fahmidan Journal, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, and Channel Magazine. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture, history, to art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on X @chimeziechika1