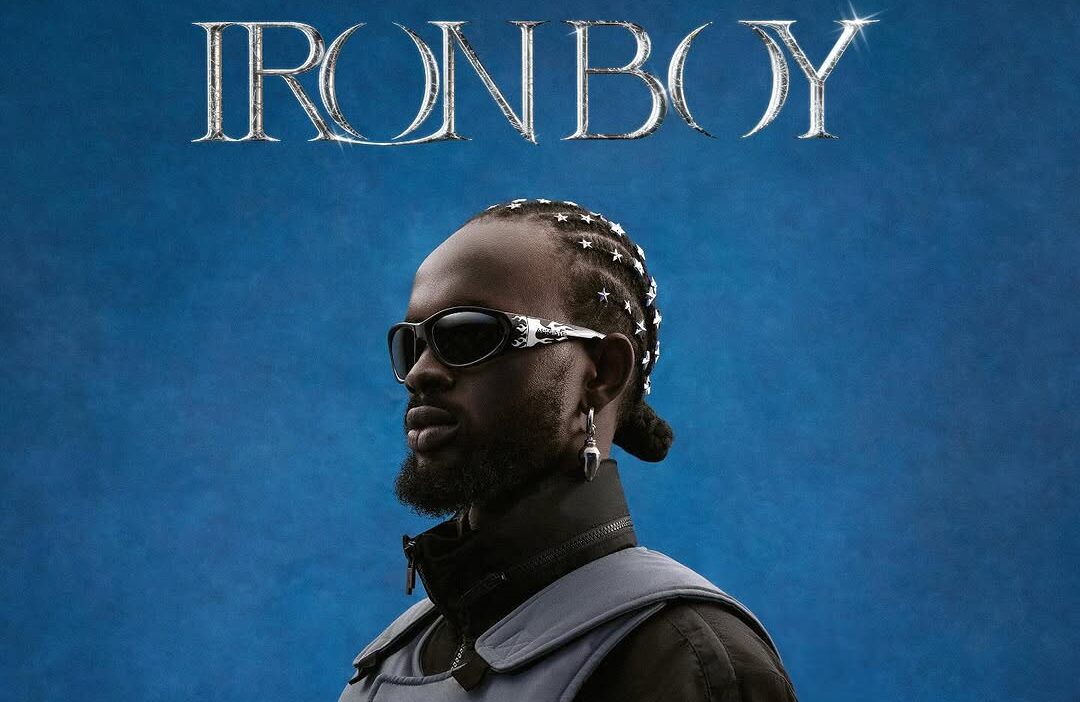

In many ways, Iron Boy is an extension of the world Black Sherif built on The Villain I Never Was, which means that its primary themes, and Blacko’s delivery of them, feel familiar.

By Patrick Ezema

On Iron Boy’s titular track, Black Sherif announces that he is “taking time out to try and be happy,” welcome news from a singer who is more popular for his troubles. The album is built on the rapper’s post-fame struggles: with ex-friends and enemies alike, with demons and with God, but mostly with himself.

Four years after “Kweku the Traveller” and the “Second Sermon Remix” brought him unimaginable fame and wealth, Black Sherif wrestles with the reality that it hasn’t brought the peace and satisfaction he thought it would, while he works even harder anyway in pursuit of even more. He has not rested for one day since his ascent, driven by a mix of ambition and a resolute desire to never return to the life he was lucky to escape.

Iron Boy, the title of this album, suggests a bulletproof, unbendable coat of armour, but it is more prophetic than descriptive for Black Sherif, who is not nearly as invincible as he wants to be. You hear his vulnerability creeping through the trippy bounce on “January 9th”, named after his birthday, on which he tries to assure you he’s okay: “Everything is under control, oh/ If I tell you I’m alright, you should know that I’m alright,” even scat-singing on the post-chorus in an attempt to convince you.

But it is a little too late: this is an outro to Iron Boy on which Black Sherif already alluded to “Trouble in my soul, war with my mind” (“The Victory Song”), battled demons (“Soma Obi”, “Sin City”) and admitted to an inability to sleep (nearly every other song). Iron Boy sees him don the cloak of vulnerability that defines his artistry, but that also means that this album is shrouded in the same dark clouds that enveloped The Villain I Never Was, if not more so.

On the effervescent 2022 track, “Kweku The Traveller”, that irrefutably cemented his stardom, Black Sherif sings a line that gained great fame for both philosophical and comedic reasons—“Of course I fucked up, who never fuck up hands in the air”. It was lost in the song’s gritty beats and the Tiktok clips it inspired, but these lines, and indeed most of the song’s hauntingly relatable lyrics, are derived from his life, from a time when the singer made crucial, costly mistakes.

On that song too, he charged himself to work twice as hard to avoid wasting another chance. Iron Boy is a reflection of that mindset, and the Rapper delivers with every bit as much quality as he did on the acclaimed The Villain I Never Was. He may have ascended to fame on a whirlwind, but he intends to make his moment in the sun last forever.

In many ways, Iron Boy is an extension of the world Black Sherif built on The Villain I Never Was, which means that its primary themes, and Blacko’s delivery of them, feel familiar. He still floats in that chasm between Highlife and Rap, a truly unique invention that likely emerged when he realised his raw, textured vocals were better suited to singing over Drill beats than rapping to them, and that his message hit harder when carried over haunting melodies than hardened bars.

This hybrid gives him a brilliant edge over both genres, and partly explains why he rarely recruits guest artistes—there are hardly any gaps in his skillset to fill, and no one quite understands the complexity of his art nearly as much as he does.

When collaborators are not brought in for artistic reasons, though, they’re brought in for commercial ones. Four years ago, a collaboration with Burna Boy for “Second Sermon Remix” accelerated his rise, and thus, the African Giant was the only guest on his debut album.

This time, he brings in two more Nigerian artistes, trying to court a massive regional market. Fireboy DML holds his own on “So It Goes”, one of the album’s brightest moments, where Black Sherif offers some of his most melodious singing.

In contrast, “Sin City”, an ode to Accra, is only weighed down by a clearly out-of-place Seyi Vibez. Black Sherif does sing over and over again about doubling his efforts to double his income, but aside from the rare misstep, he takes gentle care to ensure that commercial ambition does not compromise his art.

He steers clear of romance in a world that is saturated by it, only offering glimpses into love through the dense fog of his worries and dark reflections. “So It Goes” reaches back to a time before the money came, recalling promises to a past lover: “If you see the light remember that I was with you, when you were lost and lonely lover/ Don’t forget about me so soon”.

But Iron Boy is by no means a romantic album, and Black Sherif is keen to remind you of that. There are no happy endings in his world. The money and fame have not brought him peace, as the first verse of “Rebel Music” translates to say, while “Soma Obi”, his cry for help delivered almost entirely in Twi, even suggests that money might be a curse: “Sɛ me cash aa manya yi ne musuo”. Yet, paradoxically, his solution to true happiness is to chase even more of it, even as he admits that true peace may only come from within.

God exists for him too, as a Muslim, but unlike many religious pop stars, Sherif is not willfully forgetful of the wages of sin, the inevitability of death, or the ultimate destinations of Jannah and Jahannam, or Heaven or Hell.

It presents an interesting conundrum for Black Sherif; the internal struggle between belief and behaviour, and the reach for divine assistance whilst knowingly falling short of commandments. This self-awareness also robs him of some of the comforts of religion.

Iron Boy confronts his mortality and imperfection head on. On “Changes”, he rejects the crown placed on his head; he is neither king nor messiah, and he wishes his life was not so glamorised: “To be me I say you won’t like it I am telling you/ They want my blessings them no know what it’s like”.

That is ultimately Iron Boy’s destination: Black Sherif’s reluctant acceptance that true happiness is not tied to status, money, girls, Marijuana, or anything material, and that to find it, he must first shed the cross that has accompanied his crown.

Unlike The Villain I Never Was, Iron Boy doesn’t have its hard-hitting real Rap moments like “Kweku The Traveller”, and “Second Sermon Remix”, with Black Sherif instead choosing to explore the depths of vulnerability without the hard-guy armour.

The music that emerges is often sad, but it is truly beautiful—a realistic depiction of life from an artiste whose transparent vulnerability makes him a radical in a world where male rappers are generally expected to be strong men. In many ways, his honesty and groundedness make him the strongest man of all.

Lyricism – 1.8

Tracklisting – 1.7

Sound Engineering – 1.5

Vocalisation – 1.6

Listening Experience – 1.8

Rating 8.4/10

Patrick Ezema is a music and culture journalist. Send him links to your favourite Nigerian songs @EzemaPatrick.