Mister Johnson stages colonial modernity as a cruel pedagogy—the policy of assimilation, one that teaches aspiration without offering arrival, leaves the victim at the crossroads to the whims and caprices of Èṣù Ẹlẹ́gbà, the deity of pivotal trickster and master of crossroads.

By Olúwábùkúnmi Abraham Awóṣùsì

When I think of movies that are predated by novels, my concerns are oftentimes confounded by the verisimilitude of their adaptation. The truth is that not all conversations or scenes from the adapted novel would see the light of director’s ‘cut!’ interjections; however, the strive for maintaining proximities to the author’s world creates a fulfillment that therefore appeals to art enthusiasts. Think of movies like Lord of The Rings (Trilogy, 2001 – 2003), The Great Gatsby (2013), Lord of the Flies (1963), Sherlock Holmes (BBC Series, 2010-2017), Saworoide (1999), Oleku (1997), and others.

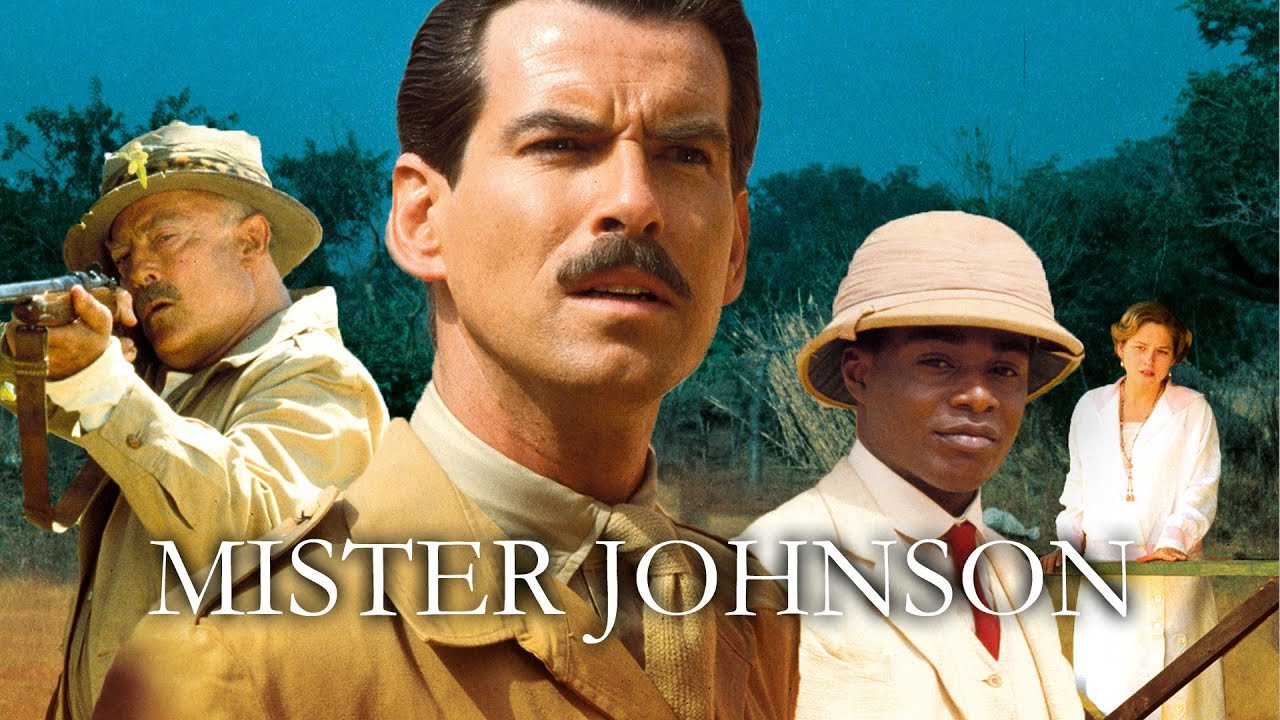

A noticeable rationale for their wide-engagement is the incorporation of character quirks, closeness to described locations, and other related elements that have hitherto glued readers to the parchment of either quasi-phantasm or quotidian ambience they are familiar with in engagement. To derail from digressing further from the crux of this essay, let me introduce you to a recent work of art that I have been thinking about and which consequently inspires this essay: Mister Johnson.

First, imagine this: a kind of cold that projects steam from your mouth as you talk, just like the way hot yams evaporate from your oval lips through mastication. Sometimes, it is involuntary. This kind of Texas cold leaves a little room for assembling your thoughts on a movie you’ve seen the previous night. Rather, what you are concerned about—as you scamper to work—is survival.

It is more about not falling prey to a hashtag death that would survive the chaos of the algorithm for a maximum of two days where everyone would pontificate on the importance of dressing fit for a cold county, and while some, imaginatively fabricate a nexus between one’s peccadillos to the just sword of God to make a scapegoat out of new age hedonists and sham-literati.

Conversely—and perhaps, akin to madness, one would think—is when I began to think of Mister Johnson; of the context Wole Soyinka cited the movie in his essay collections, Beyond Aesthetics (2019); of the eponymous character; of the sociological implication of the movie; and of writing my thoughts (with the hope of not too theoretical) about the movie. To provide a basis for this movie, I will be quoting both the synopsis of the movie and that of the actual book:

In 1920s Africa, young black accountant Mister Johnson (Maynard Eziashi) is talented enough to get an accounting job at the English colonial offices, but he quickly learns that his race prevents him from advancing to the respectable kind of position he desires. Hoping to impress his superior, Harry Rudbeck (Pierce Brosnan), he decides to fudge some numbers and save his boss thousands. When his plan backfires, however, Johnson desperately turns to even more illegal measures in order to succeed.

– Google Synopsis on the movie, Mister Johnson, 1991.

Johnson, a young native in the British civil service, is a clerk to Rudbeck, Assistant District Officer in Nigeria, and imagines himself to be a very important cog of the King’s government. He is amusingly tolerant of his fellow Africans, thinking them uncivilized; he is obsessed with the idea of bringing “civilization” to this small jungle station.

– Goodreads summary, Mister Johnson, published in 1939 and written by Joyce Cary.

Movies like this are not uncommon in capturing colonised territory in a camaraderie of condescending benevolence. Afford me your attention for another paragraph, and I will get into what I meant by this. No doubt, the movie is quite a landmark, personally, for two reasons: first, it was the first American movie shot in Nigeria; second, it starred the legendary (intentionally lionising him) Yoruba thespian, Herbert Ogunde; and also, Tunde Kelani, another Nigerian legendary cinematographer and thespian, Maynard Eziashi, who embodied the role of Mister Johnson to letter, to name a few among those who starred. Beyond these accolades, this essay intends to bifurcate its argument into two parts: to attempt a deconstruction of Mister Johnson into three sections, and to offer a theoretical argument on both neocolonialism and decolonisation in order to understand the society, one hundred and four years on, in which the film was set in.

Part One

“E be like say e don craze.”

The opening of Mister Johnson offers more than a brisk overview of what the viewers would later experience as they relinquish 97 minutes of their time to a set of moving pictures. The opening scene begins with Mister Johnson running through a path, though it is not until a few minutes later that the reason becomes clear. He stands on a nearby rock, dressed in a creamy white three-piece suit and hat, a somewhat black-striped tie, Oxford shoes, and carrying a black umbrella, and calls out to Bamu—played by Bella Enahoro—the girl he is in love with, who is washing her clothes in the river alongside her friends.

The importance of this scene lies in how it unfolds, as Mister Johnson’s character reverberates through his conversation with Bamu, the girl he intends to marry. In his attempt to woo her, he declares his wealth and his intention to make Bamu a civilised woman who would no longer work. It is a tempting offer, to which Bamu retorts (albeit mildly),“E be like say e don craze.” While some elements may be missed, to a cursory mind, a parallel of moralism is drawn, especially with the way Bamu jerked with Johnson’s comment on her breast.

Secondly, there is Johnson’s proposition to make Bamu a civilised lady. From this arises one’s first cinematic question: what does a Black man, who has never seen beyond his immediate neighbouring villages, mean by “civilising” someone? This marred identity characterised the highlight of colonialism as it not only halted the culture of the indigenous and ushered in a new one, but also caused self-loathing, which spilled into cultural distancing and affiliation to a new culture. Hence, it makes a Western psyche of an African man.

The following scenes show the circus fiesta of the Gadawan Kura (Hyena men) leading the grand procession of the emir and his entourage. Mister Johnson stands still as he watches this event, clearly not out of reverence, but epistemic disgust that classifies his disdain for such a barbaric culture! To him, his countrymen are nothing but crude and largely uncivilised, nor groomed in the way of the Queen. After the gyrations, he races to meet his lord, Judge Rudbeck, the district officer for whom Johnson works as a clerk. On his way, he is accosted by those to whom he owes money, whom he would later describe as “barbaric” and “son of a dog!” in another scene. However, he beams and blesses Rudbeck as he enters his poky office. But before this scene turns over, Rudbeck challenges Johnson on the grounds of his lateness, to which he replies that the clock is fast.

“The clock has stopped, Johnson.”

“But it was fast when he stopped, sir.”

This dialogue—either intentional or incidental—seems to capture the African concept of temporality, often described as event-based and cyclical. To the Kenyan philosopher and writer, John Mbiti, African temporality is grounded not in abstract measurement but in lived events and relational presence. The stopped clock exposes the fragility of European mechanical time when displaced into a cultural framework where time does not exist independently of human activity. Johnson’s defense—“it was fast when it stopped”—therefore, unwittingly gestures toward Mbiti’s argument that time is not something Africans control or spend, but something that unfolds through happenings, encounters, and social obligations.

As the movie progressed, Johnson marries Bamu, and during the evening celebration of his consummation, the Waziri met him and persuaded him to divulge the letters sent to Judge Rudbeck, especially the ones that might concern the Emir, and he would be paid 10 shillings. A request to which Mister Johnson replies, “you think say I be thief?” and begins singing, “England is my country! Oh! England is my home.”

The Anglophile is soon seen with Rudbeck as he plans to create a commercial road out of a path that would connect the village to the great Kano road. While Rudbeck’s vision begins to wane due to financial constraints, Johnson offers ways in which the accounts could be patched up by diverting funds allocated for other purposes towards the road and returning them once the voucher for the next budget arrives. Soon, he is caught by the treasurer, Mister Tring, another officer to whom Rudbeck was subjected, and this led to Johnson being fired.

Part Two

“Treat ‘em right, I always say. And they’re not ‘alf as black as they look.”

He finds work at the store of Sargy Gollup, a colonialist merchant, and yet, his praises for the white man never dwindle. In Gollup’s store, Johnson takes matters into his own hands; rather than wait for his wages to be paid, he steals what he calls “an advance” from the safe with a duplicated key in order to organise a party.

There is a beckoning that requires attention here; Johnson’s conduct at Gollup’s store marks a crucial intensification of his internalised colonial logic. His act of taking “an advance” is not framed by him as theft but as entitlement, which he confirms to Benjamin, his friend, a gesture mirroring the extractive practices of the colonial economy itself. This scene reveals that Johnson does not merely admire the colonial system; he rehearses it. His theft is bureaucratic rather than desperate, thus suggesting that colonial subjectivity reproduces itself not only through obedience but through imitation.

Gollup’s infamous remark—“Treat ’em right, I always say. And they’re not ‘alf as black as they look”—lays bare the racial hierarchy that structures Johnson’s aspirations, and this ushers in my earlier brush of expression—condescending benevolence.

As Gollup and Johnson go game hunting, sharing songs and plum pudding, Gollup reveals that he would have preferred Johnson to be born of a superior race. This confession crystallises the ontology of condescending benevolence at work: affection is extended only insofar as Johnson approximates whiteness; this is a form of colonial quid pro quo.

Gollup’s kindness—shared meals, leisure, and praise—is not recognition but calibration, measuring Johnson’s worth against a racial hierarchy he can never fully ascend and, to borrow from Homi Bhabha, is “almost the same, but not quite,” producing not acceptance but ridicule and suspicion. Thence, benevolence here is conditional, operating as a soft instrument of domination that masks exclusion as intimacy.

Part Three

“Get up, you son of a dog!”

“I am not the son of a dog! I am an English gentleman, and no English gentleman would walk barefoot through your disgusting town.”

After the road is completed, Rudbeck, while judging a case from an Abakaliki trader, discovers that Mister Johnson has been collecting an informal road tax from travellers. When confronted by Rudbeck—whom he later works with again after being sacked by Gollup for stealing—Johnson claims the tax is to buy beers for the road workers. Upon further inquiry into his household furnishings, Johnson admits that he has been ‘borrowing’ from the tax with the intention of repaying it. Once more, Rudbeck sacks him and orders him to leave the town.

He goes to the Zungo, a hotel built for road travellers. While there, his father-in-law, Brimah (played by Herbert Ogunde), arrives to demand that Bamu return home because Johnson cannot meet his monthly bride-price payment. In an attempt to retain his wife, Johnson sneaks into Gollup’s store, but while attempting to steal, he is caught, and a fight breaks out. This leads to Johnson stabbing Gollup to death with a receipt-holding pin. He flees but is captured. On his way to gaol, he retorts, “I am an English gentleman, and no English gentleman would walk barefoot through your disgusting town.”

This exchange marks the moment when Johnson’s cultivated Englishness finally collapses under the weight of its own impossibility. His protest is not merely defensive; it is aspirational, even declarative. By naming himself an “English gentleman,” Johnson attempts to stabilise–even in the face of stark embarrassment–an identity that has been performative from the outset. Yet, the insult that precedes his declaration, by the indigenous guards, returns him violently to the colonial order of things, reminding him that Englishness is not a matter of conduct but of race.

In this instant, language becomes a site of rupture: Johnson speaks from within a cultural vocabulary that cannot recognise him as a member. Therefore, what is exposed here is the terminal limit of colonial mimicry. In this final unraveling, Mister Johnson stages colonial modernity as a cruel pedagogy—the policy of assimilation, one that teaches aspiration without offering arrival, leaves the victim at the crossroads to the whims and caprices of Èṣù Ẹlẹ́gbà, the deity of pivotal trickster and master of crossroads.

Johnson’s tragedy, however, does not end with his execution; it reverberates beyond the narrative frame of the moving picture into the longue durée of colonial afterlife. What Mister Johnson ultimately exposes is the systemic violence that births aspiration without offering belonging, making him a social pariah. Johnson’s anglophilia—to be civilised, English, modern—becomes the very condition of his disposability, and thus, echoing Fanon’s diagnosis of the colonised subject who internalises the coloniser’s gaze in pursuit of recognition in his book, Black Skin, White Masks. Mister Johnson thus stages colonial modernity as a closed circuit—one that feeds on the labor, loyalty, and eventual sacrifice of the colonised subject while denying him historical agency, even as it claims to civilise.

Seen from the vantage point of the present, Mister Johnson becomes less a period film than a diagnostic tool for understanding neocolonial subjectivities that persist long after formal independence. As Kwame Nkrumah warned in his book, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (1965), decolonisation without epistemic rupture merely replaces direct rule with subtler forms of domination, leaving colonial values intact beneath nationalist veneers. Johnson’s internalised disdain for his culture, his faith in bureaucratic order, and his belief in development as salvation are experienced in contemporary postcolonial societies where inherited colonial logics continue to structure value, time, and success.

What Achille Mbembe terms the “postcolony” is thus already prefigured in Johnson’s world—a space where power reproduces itself through repetition rather than rupture. His story cautions against mistaking proximity to power for emancipation and development for dignity.

What the film ultimately leaves us with is not just the image of a man undone by ambition, but a haunting question: how many Johnsons continue to be produced in societies still governed by inherited clocks, borrowed ideals, and roads that lead everywhere except home?

Olúwábùkúnmi Abraham Awóṣùsì is a second-year Art History Fellow at Texas Tech University, a curator, and a researcher whose work focuses on Yorùbá visual culture at the intersection of indigenous knowledge systems and contemporary theory. His writing has appeared in Door Is A Jar, Ogbon Review, and elsewhere.