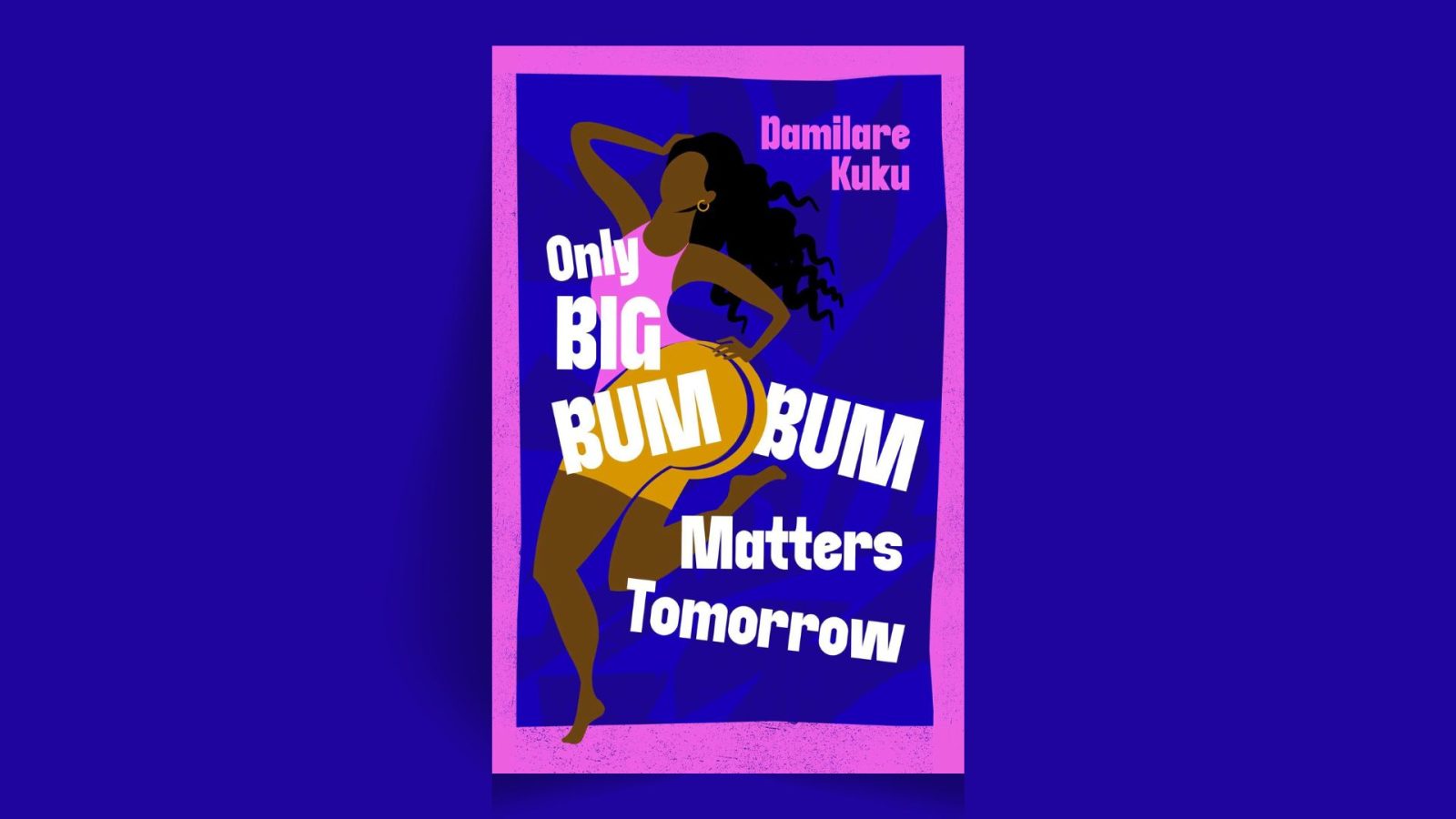

Damilare Kuku’s Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow is a novel that speaks clearly to a generation of women tired of being told how to behave, how to look, and how to live.

By Evidence Egwuono

“I plan to renovate my bumbum in Lagos, live there for some time, and hopefully meet the love of my life!”, Damilare Kuku begins her sophomore book, Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow.

Kuku rose to fame among readers after the publication of her 2021 debut book, Nearly All the Men in Lagos Are Mad. One reason why this book became a Roving Heights bestseller is because of its relatability, both in its title and its theme, to the many Lagosians who have had their fair share in the madness of Lagos men.

As a writer with a bias for bandwagoning, I thought twice before purchasing this book to read due to its popularity, but was later intrigued by some stories in the collection, particularly how Damilare Kuku infuses humour while discussing grim issues in society. It does seem like this author has established her forte as a storyteller who is unafraid to tell stories of women’s struggles in society, sealing them with unconventional and curiosity-arousing titles.

Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow is built around the interconnected yet distinct lives of four women: Témì, Ládùn, Aunty Jummai, and Hassana. Each of these women grapples with different challenges, mostly shaped by the emotional residues of their past. Ládùn, the first child of Hassana and Titó, is the prodigal daughter who returns for her father’s burial after years of disappearance. Hassana, her mother, is the fierce matriarch who is trying to reconcile her own grief with the worry that she may be losing her second daughter as well.

Aunty Jummai, Hassana’s sister, is the ever-present loudspeaker—opinionated, dramatic, and bitterly comic—who thrives on other people’s chaos and heartbreak, though rarely her own. And then there is Témì, the primary narrator, whose seemingly ridiculous proclamation to “renovate her bumbum in Lagos” sets the book’s central conflict in motion.

Kuku uses this cast of carefully crafted personalities to stage a multi-generational debate on beauty, desire, self-possession, and motherhood. In many ways, Témì’s desire to undergo a BBL becomes a cipher for everything these women have buried within themselves. Through the eyes of Témì, we see the implications of societal and familial expectations that women must always bend, if not their bodies, then their dreams, to fit someone else’s approval.

From a place of observation, there is a lot to be said about the emotional honesty in Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow, and by extension, about Kuku. She has a penchant for slipping heavy truths between bursts of humour, similar to what we find in her first book. One second, you’re laughing, the next, you’re swallowing a lump. It is this ability to switch tones, to balance the comedic with the tragic without losing the reader, that makes Damilare Kuku’s storytelling feel so alive.

While Témì is the story’s compass, the novel refuses to flatten her into a Gen Z stereotype. Yes, she is bold, perhaps even reckless in some instances. But she’s also introspective, thoughtful, and aching to be seen. Her declaration to get a BBL is not just a cosmetic decision. As we discover while reading, it is a response to years of longing to be seen and frustration at being constantly body-shamed. It is not so much about becoming desirable as it is about reclaiming her body in a world that has used her shape as an emblem of deficiency.

However, what is interesting is how the other women in Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow reflect their own insecurities onto Témì’s decision. Hassana, her mother, is haunted by her own body image, especially her sagging breasts. Aunty Jummai, in her obsession with decorum and control, hides the reality that her own life has been reduced to watching others live. And Ládùn, who fled the town years ago, sees Témì’s move to Lagos as a mirror of her own choices, perhaps even mistakes. This layering allows the novel to move beyond a singular storyline focused solely on the BBL.

What makes Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow especially important is the space it creates for a different kind of African female protagonist, one who is not bound by moral perfection or respectability politics. Témì, the protagonist, is messy, impulsive, occasionally naive, and makes some foolish decisions and mistakes.

But the author sends a powerful message through her protagonist. Temi is not perfect, nor is she elevated or given a super-human status. She is not punished for her choices, nor is she sanctified. She is simply allowed to be and exist on her own terms. Damilare Kuku emphasises in Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow that the African woman has a fundamental right to be as complex as she desires.

Beyond the central theme of body politics, the novel is also a study of the relationships that exist between women and the importance of communication. Hassana and Aunt Jummai, who were once inseparable as kids, drift apart as adults; Ladun and Temi’s sisterhood bonding becomes messy after the former leaves her parents’ home; Hassana struggles with parenting Ladun because she believes her daughter hates her. But at the root of these rifts is not malice, but misunderstanding born from years of carrying burdens society teaches women to endure without protest. And in choosing not to speak, they become strangers to one another.

It is important to point out that Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow employs multiple points of view. Each of the women get to tell their story and readers have a nuanced perspective of their lives.

However, this began to feel overindulgent, especially in the latter half of the book. The chapter shifts were jarring, with some voices sounding too similar in cadence. The plot also occasionally leaned on exposition rather than action, slowing the pace. However, these are forgivable imperfections considering what the author achieves in this novel.

Damilare Kuku’s Only Big Bumbum Matters Tomorrow is a novel that speaks clearly to a generation of women tired of being told how to behave, how to look, and how to live. And for that reason alone, this is a story worth reading.

Evidence Egwuono Adjarho is passionate about African literature and dedicates her time to amplifying it through book reviews and video contents. She is currently undergoing training as a photographer. Connect with her on Instagram, X, Facebook, and LinkedIn: @evidence_egwuono