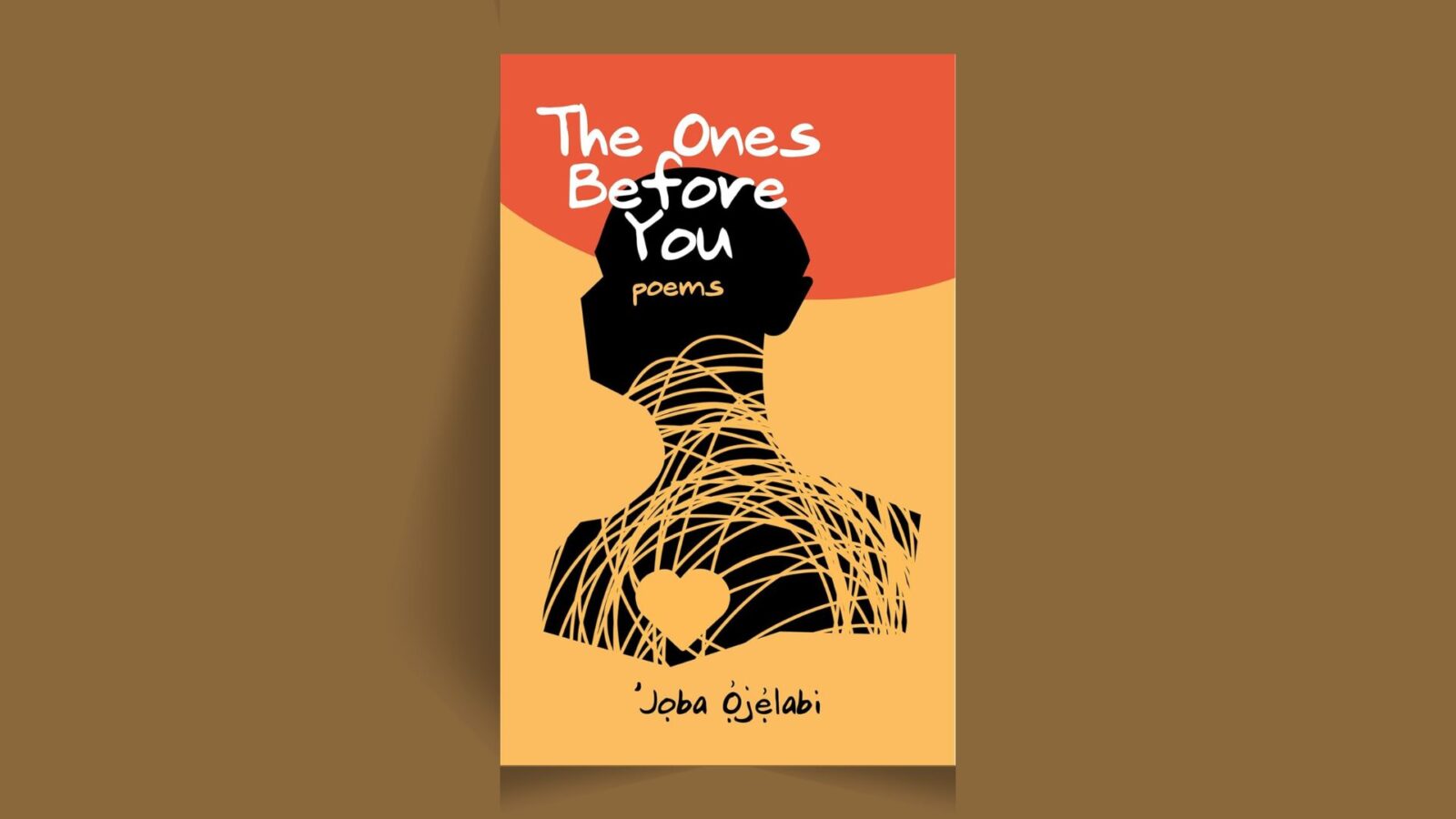

The Ones Before You is a tender excavation of self and society. With each poem, Joba Ojelabi carves space for reflection, urging us to confront what we inherit, what we carry, and what we choose to become. It is a collection that listens as much as it speaks.

By Evidence Egwuono Adjarho

There is an inherently beautiful thing about writing fiction. The writer is often given the leeway to express themselves however they choose, having come in contact—directly or indirectly–with various experiences that can be reproduced in their writings.

It is in this light that the writer is often given the sobriquet of a god breathing life into what never existed, and developing characters, places, and emotions so vividly that the lines between fiction and reality begin to blur. These were thoughts I noted to myself while reading Joba Ojelabi’s chapbook, The Ones Before You.

A collection of poems, The Ones Before You delicately captures the breadth of human experience, rendering it with such realism that each poem reads like a personal tale shared by a seasoned raconteur.

Themes of love and the complications that may arise from loving such as rejection and loneliness recur throughout the collection. The poems in the chapbook also grapple with the weight of societal expectations, especially the kind passed down from one generation to the next, which often shape and sometimes distort identity. As the poet journeys inward, there is a strong current of introspection, mostly an attempt to make sense of the self amid external pressures.

The opening poem of The Ones Before You introduces a powerful and thought-provoking question: whose burden do we carry in our lifetime? Titled “Masquerade”, the poem delves into the burden of inherited responsibilities and the unseen weight that shapes human lives. It reflects on how individuals are often born into expectations they did not choose, yet are compelled to fulfill. This burden is particularly pronounced in the context of the African child, who is made to carry a “double yoke”—living not only for themselves but also for the dreams their parents could not achieve.

Typically, in African households with parents denied formal education, the children are often pushed to succeed academically and achieve what their parents could not. In psychological terms, this is known as projection, where one’s unfulfilled desires are imposed onto another.

“Masquerade” captures this dynamic by using ‘mask’ as a motif for the different roles and identities a person is forced to assume. These masks represent societal expectations, family hopes, and personal compromises. The persona in the poem aptly refers to this as a curse.

Subsequent poems in The Ones Before You explore a wide range of human emotions, but the theme of love emerges as particularly dominant starting from the second poem. However, Joba Ojelabi does not approach love through the lens of cliché or overused romantic tropes. Instead, he offers a nuanced portrayal that embraces the love in its entirety: its vulnerability, its tenderness, and even its pain and rejection.

In the poem, “For When Bella Doubts”, Joba Ojelabi presents a deeply intimate moment between the persona and their lover. Here, love is not grand or theatrical. It is quiet, personal, and deeply felt. The persona gently reassures their lover of their beauty, choosing their words with the careful precision of a surgeon.

What makes the poem especially moving is its simplicity. But this is where the author’s poetic skill shines. He demonstrates how ordinary words can convey extraordinary emotion. By the end of this poem, the emotional effect is undeniable. Just as the persona’s words lift Bella’s spirits, they also touch the reader.

Similarly, “The Girl from My Poems” probes the delicate tension between vulnerability and restraint in romantic relationships. The poem explores the emotional uncertainty that often comes with opening one’s heart to someone else, particularly the fear that such openness might not be fully understood or reciprocated.

The persona, caught in this emotional limbo, “attempts to keep emotions obscure”. This concealment, however, is not due to a lack of feeling but rather a fear of how their lover might respond to such raw honesty. In this way, Joba Ojelabi captures the internal conflict many experience in love: the desire to be fully seen versus the fear of being misread or rejected.

Yet, love is not the only concern of The Ones Before You and this, perhaps, is one of the reasons I find myself increasingly drawn to poetry. Unlike the novel, where each chapter must be clearly linked to advance a linear narrative, poetry thrives in its brevity and openness. A collection like this allows the poet to present various themes side by side, leaving the reader to make the connections. In this way, the reader becomes an active participant in meaning-making, almost like a plot organiser.

Another significant theme explored in the chapbook is loneliness and rejection, both of which are inevitable phases in the human experience. One poem that stands out to me in The Ones Before You in this regard is “A Nomad’s Ghazal”. The poem paints the figure of a nomad—a wanderer in constant search of belonging—as a metaphor for the persona’s emotional and spiritual dislocation. The idea of a home that is unreachable, whether physically or emotionally, is the focal point here and evokes a profound sense of loss.

In The Ones Before You, Joba Ojelabi also raises a profound question about the nature of comparison: if individuals respond differently to similar circumstances, why then should one person’s reaction be used as the standard for judging others? This idea is poignantly explored in “Men Do Not Tally”. The author employs language rich in metaphor to illustrate the varied ways people, with a focus on men, navigate hardship and pressure. He writes:

While some go through the forging fires,

others melt away,

By the poem’s conclusion, the poet reinforces the core message: “because, mentally, men do not tally…” In other words, our psychological makeup is not the same, and any attempt to standardise human reactions is not only flawed but also unjust.

What stands out most for me in The Ones Before You is how it embodies the classical ideal of utile et dulce—that is, poetry that is both instructive and entertaining. Joba Ojelabi strikes a delicate balance between delivering thoughtful reflections and crafting verses that are enjoyable to read. The chapbook avoids the pitfalls of overly serious or moralistic writing, resulting in a refreshingly compelling collection.

Ojelabi reminds readers of his versatility as a poet; he seamlessly adopts different personas throughout the collection—sometimes a teacher, sometimes a jester, and at other times, a moralist. Take, for example, “Green Lights” The title is a clever pun on the colloquial expression used when a woman gives a man signs of mutual interest. The poem plays with this modern lingo while still including a commentary on attraction and consent.

Similarly, “How to Love a Thick Lady” and “Small Packages” are light-hearted but no less meaningful poems that challenge shallow perceptions of beauty. These poems emphasise the importance of respecting and valuing women beyond physical appearances, all while maintaining a humorous and mischievous tone.

The Ones Before You is a tender excavation of self and society. With each poem, Joba Ojelabi carves space for reflection, urging us to confront what we inherit, what we carry, and what we choose to become. It is a collection that listens as much as it speaks.

Evidence Egwuono Adjarho is a Gen Z who loves God. She is passionate about the power of African literature and dedicates her time to amplifying it through book reviews and video contents. Connect with her on Instagram, X, Facebook, and LinkedIn: @evidence_egwuono