Whether or not an Oscar ever comes, Nollywood’s challenge is to chart a path that does not compromise its essence while still claiming the cultural legitimacy—and the soft power—that global recognition confers.

By Joseph Jonathan

When the Nigerian Official Selection Committee (NOSC) confirmed that Nigeria would not be submitting a film for consideration at the 2026 Academy Awards, the announcement came with a mix of resignation and déjà vu. This is the third time since 2019 that the committee has chosen silence, joining 2021 and 2022 as years when the world’s second-largest film industry had nothing to present at World Cinema’s most prestigious stage.

The contrast is striking. Egypt, Morocco, Senegal, South Africa, and Tunisia all confirmed their entries for 2026, adding to long histories of consistency in the Best International Feature Film category. Nigeria, meanwhile, the self-declared “giant of Africa” in cinema, remains absent.

It is tempting to frame this simply as failure: Nollywood, despite its size, struggles to consistently meet Oscar standards. But the truth is more complicated. Nigeria’s recurring absences reveal deeper questions about the structural design of Nollywood, the colonial hangover of the English language, and the ambiguous place of the Oscars in Nollywood’s cultural imagination.

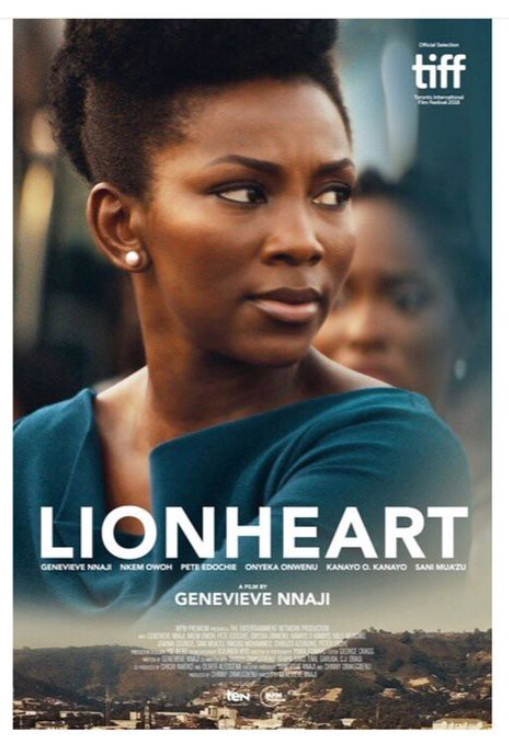

Nigeria’s relationship with the Oscars has been anything but steady. In 2019, Lionheart, Genevieve Nnaji’s directorial debut, became Nigeria’s first-ever submission. But within weeks, it was disqualified: the film, which was primarily in English with some Igbo dialogue, failed the Academy’s requirement that submissions must be more than 50% in a non-English language.

The decision sparked outrage online, not least because English is Nigeria’s official language and a legacy of colonialism. The disqualification felt like a slap, a reminder that Nollywood was being asked to play by rules written without it in mind.

In 2020, Nigeria submitted Desmond Ovbiagele’s The Milkmaid, a Hausa-language drama exploring insurgency and gendered violence in Northern Nigeria. The film passed the eligibility stage but did not make the final shortlist. Then came silence: no submission in 2021, none in 2022.

In 2023, C.J. “Fiery” Obasi’s monochrome fantasy, Mami Wata, carried Nigeria’s hopes. The film had won a Sundance prize for cinematography and drawn strong critical acclaim, yet it did not make the Academy’s shortlist. In 2024, Prince Daniel Aboki’s Mai Martaba was submitted but failed to make the nominations list.

By 2025, the pattern has hardened into something familiar: a disqualification, a short-lived run, or no entry at all. In the most recent round, six films were reportedly submitted for consideration, but the Nigerian Official Selection Committee (NOSC) ultimately voted “no submission” again.

Nigeria’s absences are particularly puzzling because Nollywood is not invisible globally. On Netflix, Nollywood films regularly dominate viewing charts across Africa and reach diasporic audiences. Box office records in West Africa are consistently broken by Nollywood films and Nigerian directors are appearing more frequently at international film festivals to critical acclaim.

Ironically, this vitality and virality have not translated into Oscars consistency. South Africa has submitted 20 films since 1989, winning once (2006’s Tsotsi) from two nominations. Morocco has submitted 21 times since 1977 (no nominations). Tunisia has had 12 submissions since 1995 (one nomination). Egypt, being the first African country to submit a film, has 39 submissions since 1958 without any nominations. Nigeria, by comparison, has only three submissions in history, with one disqualification.

This paradox is revealing. Nollywood is designed primarily for its domestic and African audiences. Its industrial model is built on speed, volume, and commercial return rather than the slow, prestige-driven pathway of festival-to-Oscar campaigns.

Serving the home audience is not a weakness—it sustains the internal economy and affirms cultural identity. But cultural currency abroad also matters: recognition brings prestige, attracts investment, and amplifies Nollywood’s soft power.

Nigeria’s recurrent no-show at the Oscars, then, is less about failure than about a balancing act between local relevance and global legitimacy. On one hand, Nollywood’s primary responsibility is to the millions of Nigerians and Africans who buy cinema tickets, stream films, and keep the industry alive; chasing the Oscars at the expense of that core audience risks alienating the very base that sustains it.

On the other hand, global recognition functions as cultural capital: it opens doors to international co-productions, unlocks distribution pipelines, and strengthens Nigeria’s claim to soft power on the world stage. This is why the absence of Nigeria at the Oscars feels so loaded. It is not simply a missed chance at a gold statuette, but a reflection of the unresolved question of whether Nollywood wants to remain an inward-facing industry or evolve into a global cinema force capable of shaping how African storytelling is viewed, valued, and consumed worldwide.

If there is one recurring barrier to Nigeria’s Oscar bids, it is language. The Academy requires that more than half of a submitted film’s dialogue be in a language other than English. For countries where English is the lingua franca—Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana—this rule can be crippling.

Lionheart fell victim in 2019. In a similar way, Eyimofe: This is My Desire, which premiered to critical acclaim at the 2020 Berlinale and could have been a worthy contender in the year 2021 when Nigeria had no submission, stood no chance from the start because most of its dialogue was in English.

The film’s muted theatrical release a year later only underscored how little infrastructure exists to push such works beyond domestic admiration toward global recognition. It is a similar story in Kenya, where Memory of Princess Mumbi (2025), despite its success on the international festival circuit and warm reception from critics, is automatically disqualified on the same grounds.

Here lies the colonial irony: English was imposed on countries like Nigeria and Kenya through colonialism. Today, those same countries are told that English disqualifies them from “international” recognition. The definition of what counts as “foreign” reflects the Academy’s own blind spots, privileging certain linguistic traditions while penalising others.

Other countries have learned to adapt. South Africa often produces multilingual films blending Zulu, Xhosa, Afrikaans, and English, ensuring eligibility. The UK, meanwhile, has found a way around the same barrier by funding and co-producing foreign-language films abroad, leveraging wealth, reach, and soft power. It’s an irony that the former colonial power now benefits from the linguistic and cultural remnants of its former colonies, an arrangement that occasionally feels like quiet cultural extraction. In 2018, for instance, Zambian filmmaker Rungano Nyoni’s I Am Not a Witch was submitted by the UK for the 2019 Oscars.

That dynamic now resurfaces in the curious case of Akinola Davies Jr.’s My Father’s Shadow, which premiered at Cannes 2025, winning the Caméra d’Or Special Mention and drawing wide critical acclaim. Despite being primarily in English, the film was recently announced as the UK’s official entry for Best International Feature Film at the 2026 Oscars.

For Nigeria, such a submission might have been impossible. Yet, for the UK, it is a manageable hurdle: one that can be navigated through institutional support, co-production structures, and the ability to audit the film’s linguistic composition in ways less structured industries simply cannot. In essence, the UK has learned to turn its colonial legacy into cinematic capital, while countries like Nigeria remain stranded without comparable state backing or infrastructure.

Beyond language, there is the matter of quality, though not in the reductive sense often thrown at Nollywood. The reality is that many Nigerian films are made with commercial gains rather than awards ambitions in mind, and as such, they often fall short of the technical and artistic benchmarks typically associated with Oscar contenders. But for the handful that do rise to that level, the challenge lies in positioning: they are rarely nurtured within the ecosystem of festivals, distribution strategies, and campaign machinery that can translate critical merit into Oscar success.

Countries like Tunisia, Morocco, and South Africa treat Oscar submissions as cultural diplomacy. They invest in films that meet international standards, fund distribution and awards campaigns, and deliberately chart films through the festival circuit.

South Africa has the National Film and Video Foundation (NFVF), which not only funds films, coordinates submissions, and bankrolls campaigns, but also runs the South African Film and Television Awards (SAFTAs) as a national platform to celebrate and elevate its industry. Morocco and Egypt have state-backed cultural agencies that treat Oscar visibility as an extension of national soft power. These infrastructures ensure that by the time a film reaches the Academy, it has already been polished, positioned, and pushed into the right circles.

In Nigeria, such state-level coordination is absent. The NOSC, often working with limited resources and little consensus, is left with films that may have domestic popularity but not the infrastructure to compete internationally.

Nollywood’s economy rewards quantity: films are made quickly, cheaply, and often aimed at recouping costs within a few weeks or months of release. International awards campaigns, by contrast, require patience, funding, and long-term strategy. This mismatch contributes to Nigeria’s inconsistency with submissions —it simply lacks the pipeline to sustain regular Oscar bids.

But this raises a more provocative question: should Nollywood care?

On one hand, the argument for caring is straightforward. The Oscars are more than an awards ceremony; they are a global spectacle that shapes cultural hierarchies. A nomination, or even a shortlist, translates into visibility for a film and its makers, bringing international distributors, critics, and audiences into Nollywood’s orbit.

It opens doors to co-productions, festival slots, and investment pipelines that can strengthen the industry at home. In this sense, Oscar recognition functions as cultural diplomacy: it signals that Nigerian cinema is not only commercially viable in Africa but also artistically competitive on the world stage. For a country still negotiating its image abroad, that kind of soft power is not trivial.

Yet the counter-argument is equally compelling. Why should Nollywood seek validation from an American institution whose rules do not reflect the realities of Anglophone African cinema? The 2019 disqualification of Lionheart remains emblematic: a film was penalised for speaking the country’s official language, a direct inheritance of colonial history.

To many, this emphasised how the Academy’s structures are not built with Nigeria in mind. In that light, Nollywood’s strained resources may be better spent strengthening its own festivals, awards, and distribution channels rather than chasing recognition that is, at best, uncertain and, at worst, exclusionary.

There is also the question of Nollywood’s DNA. This is an industry founded on speed, accessibility, and direct appeal to mass audiences. It thrives by making films for Nigerians first, not for festival juries or Oscar voters.

If prestige recognition demands that Nollywood abandon the qualities that make it unique, then perhaps the pursuit is not only unnecessary but counterproductive. After all, Nollywood’s global visibility on platforms like Netflix, Prime Video, and Showmax already demonstrates that the industry can travel without the Academy’s blessing.

And yet, dismissing the Oscars outright would ignore the symbolic weight they still carry. A Nollywood Oscar nomination would not only be historic; it would shift how African cinema is perceived globally, challenging stereotypes of the continent’s filmmaking as either low-budget or purely ethnographic.

It would also inspire a generation of Nigerian filmmakers to see their work as capable of playing on the world’s biggest cultural stage. The question, then, may not be whether Nollywood should care, but how much, and on what terms?

Perhaps, the more honest conclusion is that Nollywood is still negotiating its relationship with the Oscars. The tension between serving its home audience and seeking global recognition is not easily resolved, nor should it be. The industry’s vitality lies in its ability to be both local and global, commercial and artistic, fast-paced and prestige-driven. Yet indifference comes at a cost.

In an interconnected industry where visibility attracts investment, talent, and influence, stepping away from the Oscars means ceding ground in a game that others are playing to win. Whether or not an Oscar ever comes, Nollywood’s challenge is to chart a path that does not compromise its essence while still claiming the cultural legitimacy—and the soft power—that global recognition confers.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big