By and large, we find in Umukoro’s Fenestration, poems that are alive, awake and aware; poems that sometimes tilt towards the desire of breaking the fourth wall.

By Daniel Echezona

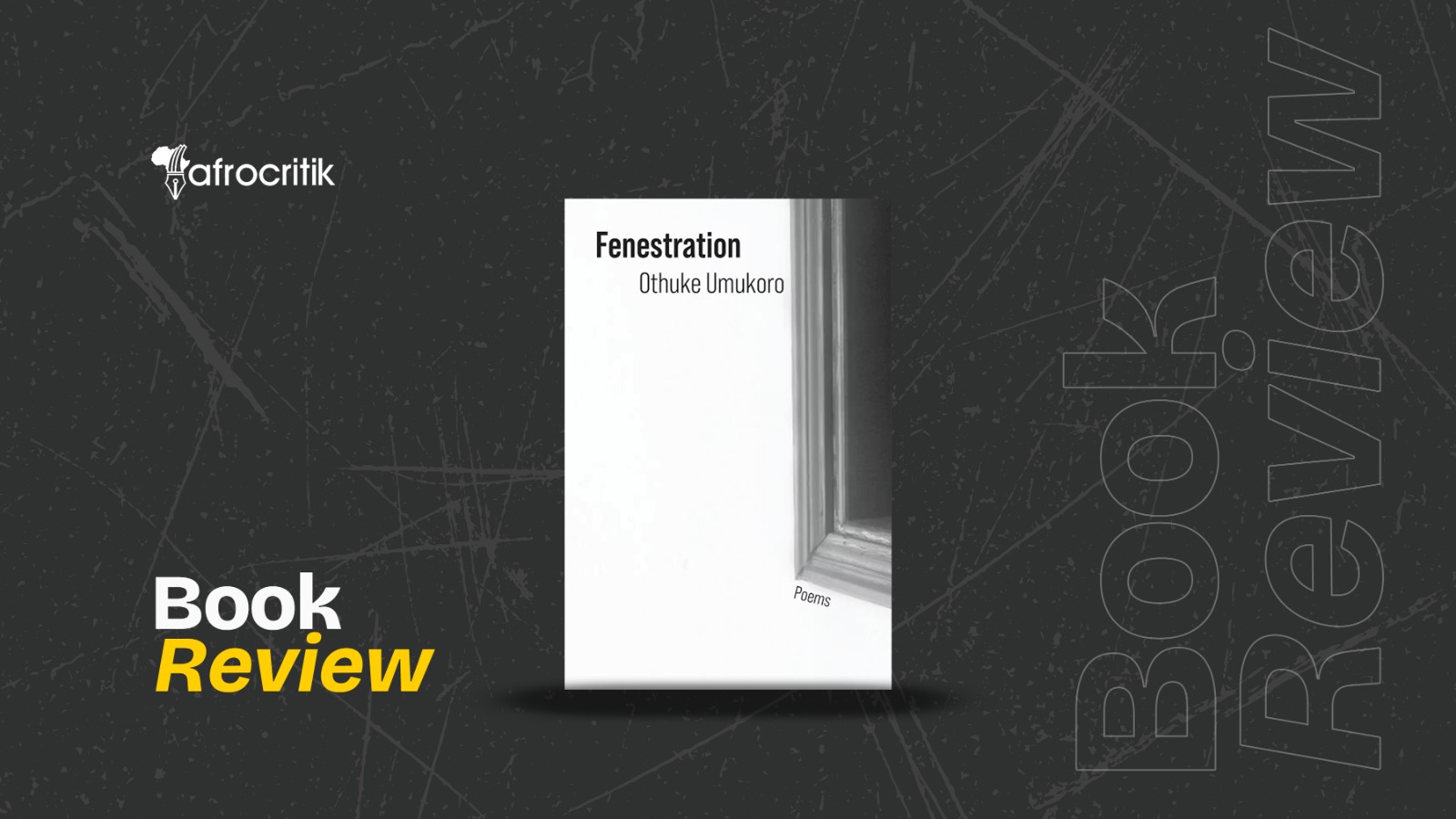

Four years after winning the Brunel International prize for African Poetry, Othuke Umukoro published his debut poetry collection, Fenestration, which won the 2024 X.J Kennedy Prize, via Texas Review Press (2025).

Praised by Mark Levine for its blend of lush lyricism with observational directness, the poems in the book no doubt brim with echoes of a voice that is both urgent and calm, both desperate in its plunging back into memory and disciplined in the way it approaches its subject. And if there is an instance to agree with Salvatore Quasimodo that poetry is a “revelation of a feeling that the poet believes to be interior and personal, which the reader recognises as his own”, then it is with Umukoro’s collection. Through its pages, one encounters a vast range of themes—most of which are perfectly laid out—and lines as timeless as they are emotional.

From the very first lines of each poem, Umukoro holds his reader by the hand and shows him round his world— their world. In the poems throbbing with grief, the poet knows better than to let emotions spill over, and with this restraint, he manages to keep his poetic intentions from crossing the rubicon.

In the poems about his father’s death (three poems bearing related titles), the poet leads us into the terrain of his loss, in a measured chronicling of the details that precede and succeed the death. He elevates the death of a parent to the universal experience that it is, although he anchors it so much in the personal. There are references to a malaria bout he fights at age nine, memories of his father sourcing herbs for his treatment.

In “The Year Before the Year Before the Year Before the Year My Father Died”, the poet hybridises his expression, leaning on a stretch of prose to launch into a memory that is seemingly central to his perception of his father. The poem establishes a more stable ground for the reader’s empathy, much of which is earned in the third poem about the death of this father, the poem which arguably bears the existential heart of Fenestration, and in which we encounter lines like: “I make plans with people/ & pray they cancel.’ and ‘On the white/ porch I take the poem/ apart again”.

Against one of the teeming opinions of poetry which claims that a poem’s ultimate strength lies in its rendering of imagistic lines and rather obscure-but-beautiful metaphors, the poems in Fenestration thrive in a deceptively simple rendering of metaphors, (almost) all of which earn their place in the poems.

Where some of the poems, like “This” and “Grit” risk being too prosaic that their poetic strength is furled in minimalism, to an extent where a metaphor-centric reader could dismiss them, the poems are redeemed by the poet’s measured attention to rhythm.

This, we can say, is one of the poet’s strengths as regards the elements of sound in Fenestration. The paucity of the sound scheme, which may be a reflection of the poet’s unconscious neglect, would have been irredeemable if these lines were not held together by a strong noose suggestive of a master artist. Still, with the maddening shift towards subtlety and imagery in modern (African) poetry, readers find themselves longing for that musical quality in poetry, reminiscent of what Edgar Allan Poe describes as “the rhythmical creation of beauty”.

The poems in Fenestrations may not succeed if they pose as being musical — internal rhymes, striking alliterations, conscious focus on any rhyme scheme; we find none of these — but of course, when we take them as calm recollections, narrations and descriptions of pivotal moments in the poet’s life, we can arrive at the point where the poet has built us a tent of understanding.

On the point of understanding, the reader — having come to terms with the collection’s general structure and texture — would begin to deal with what I choose to call ‘a landing issue’ in some of the poems, particularly the ones that open Fenestration. The poems sometimes feel as though they just taper out, rather than end.

When Umukoro ends a poem with these lines: “What is memory if not commitment?/ These dark clods” (Prologue); there is, for the reader (or there was, for me), a sense of something unfinished. Whether it is a cliffhanger he aims at, or simply a defiant attempt to hang in-media-res, the side effect on the reader should not be neglected; how whatever emotional buildup achieved with earlier lines risks losing some poetic potency. It is this same landing issue, and what it does to the reader’s sense of closure, that we encounter in the ending of a poem like “Grit”:

what splinters

inside me splinters

because it splinters.

The ending of “I Wakeful” too, although a brave leap in style, also brings me to this landing issue: ‘because the two live beneath each other/ & promise &’. So ends the poem. What I seek is not a rush of completeness, not a heady ungestüm, but a simple resolution that knots my entire experience with the poem; at least as a reader, I seek this when I go into all poems I intend to ‘hear’ from. But Umukoro really seems not to care about this, more obvious as he states in his poem: “All that talk/ about the best way/ to end a poem. I don’t./ Care’ (Poem of the Day)

For a collection that devotes nearly half of its poems to nostalgia, there is a justification for the priority of emotional connection over a flex of poetic language. The downside of this, however, could be that—in some of the poems— the reader has to contend with the specificity of the poems. The reader sometimes faces the task of narrowing down the poet’s cultural particularity to match his own world.

“Late Spring” begins with these two lines: “The chiaroscuro/ of tulip poplars” and goes forward to a “scarlet tanager”. These are anchored in the peculiarity of a particular place in a particular season, just like “Winter in Iowa City”. Generally, this does not count as a flaw, because poems are rooted in the idea of place, and it is even one of the major aims of poems to bring you to places you have never been, and what the poet attempts in poems like “Winter in Iowa City” brings to mind Plutarch’s sentiment that “poetry is a painting that speaks”.

In her blurb of the book, Tracie Morris describes Fenestration as heart-centric. One can agree with this description if we consider the tender poems like “This”, “Understory”, “Hollow” and the three poems titled about his father’s death. We can agree that the collection bears ‘tender poems of discovery’ when we look at the novelty of the metaphors, which reveal new ways of viewing disparate things, and the couple of rhetorical questions that hold their own weight.

But of course, we must bleep out (and forgive) some of the questions which come off as spineless and weak attempts at faux-poetic intensity. The poems reach the quiet places in quiet ways, and if one cares long enough, the quiet flaws manifest too. Take, for instance, these two questions: ‘What is memory if not commitment?’ (“Prologue”); and ‘…The fungus green/ of this month, my father, how could it mean go?’ (“The Year My Father Died”).

One can see how the former line is bereft of the poetic finesse (particularly when viewed from its position in the poem), how disparate the tenor and vehicle of the metaphor are. Reading the poem, one cannot help but wonder, how is commitment the sole definition of memory? And while stretching a bit further, one might find meaning in this line and assume it to be the poet’s intended meaning; there is still this possibility that the line was thrown into the poem as an afterthought with near-irrelevance in the general breadth of the poem.

In the latter line, the poet’s comparison between the green of fungi and the green of a traffic light (go) is a novel metaphor, one of such that makes a reader agree with Tracie Morris that “[the lines] stay with [you] long after the end of the page”.

It will not be difficult for a reader to see how much of a disciplined poet Umukoro is, how tightly-crafted most of his lines are, and how precise his metaphors and images are (when he gets them right). However, sometimes the poems run the danger of being monotonous in places, and this is a matter of thematic preoccupation.

About seven poems in Fenestration are themed on slavery and colonial violence, and somehow they look like segments of one long poem, in the sense that one picks off where the other stops, and what is said in one echoes again in the next (see poems like “Mass”, “Grit”, “Thrust”) without any much development in strength.

Thus, we approach each poem about slavery, hoping to note a sort of profundity that makes it distinct from the other. The danger of this is the tendency of fatigue on the part of the reader, understandably. However, there are poetry collections anchored on singular themes which form the backbone of the poems (think Oluwaseun Olayiwola’s Strange Beach, or Tracy Smith’s Wade in the Water) which readers might still manage to read without fatigue.

Perhaps, what we get in Umukoro’s case is a result of the calmness of his works, even while he attempts to scream. In the absence of startling/surreal images (an absence I’m grateful for), it is easy to get inundated with the softness and ask for something different. But in all these, one cannot deny the expansiveness of the Fenestration’s scope: HIV, slavery, grief, nostalgia, existential dread, and consciousness.

By and large, we find in Umukoro’s Fenestration, poems that are alive, awake and aware; poems that sometimes tilt towards the desire of breaking the fourth wall. We see this in lines like: “I must carry the poem this way/ far to the middle/ where a canoe, stuck, waits” (“Beneath Silence”); the end lines of “The Year Before the Year Before the Year Before the Year My Father Died”; and in the ritualistic cadence of “Passing”.

The Semi-anaphoric repetition of “I am passing the poem to…” elevates the poem to a sort of liturgy, and each memory exhumed becomes a stakeholder in the poem; each person remembered is a co-heir to the nostalgic cubicle the poet builds.

Fenestration—with its strengths and flaws likewise— presents language at its most distilled and most powerful. The faults are there, the beauty is there, and by the last poem in the book, the reader looks into his hands and finds an undeniable—even indelible—evidence of a poetic journey just experienced.

Daniel Echezona is a writer and student of the University of Nigeria.