There is a shared history with the stories that matter for queer representation. After screening at prestigious international film festivals and winning coveted international awards, the movies aren’t often screened or shown in the director’s home country.

By Seyi Lasisi

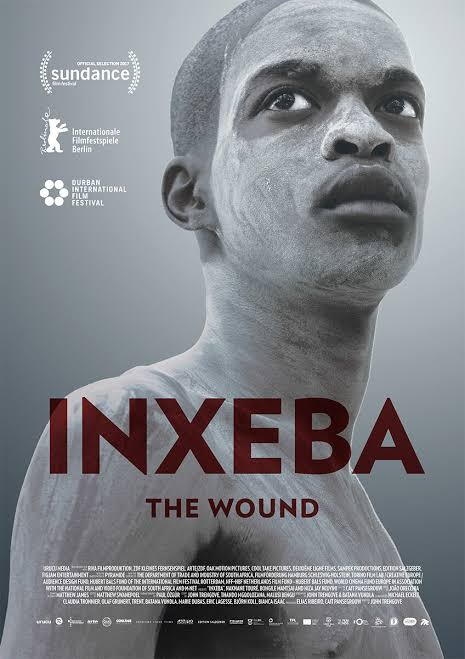

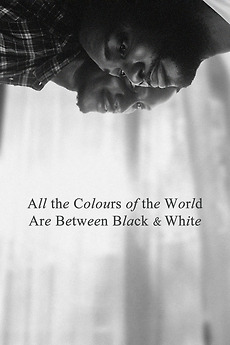

Annually, and somewhat obligatorily, various liberal and forward-thinking digital African culture publications curate listicles of Queer African films during Pride month. These listicles often feature works like Guinean Mohamed Camara’s 1997 Dakan, interpreted as Destiny, South African John Trengrove‘s 2017 Inxeba, interpreted as The Wound, and Cameroonian Estelle Robin‘s 2011 documentary, Coming Out of the Nkuta. From Kenya, there are Wanuri Kahiu’s Rafiki (2018), Peter Murumi‘s documentary, I Am Samuel (2020), and Jim Chuchu‘s short film collection Stories of Our Lives (2014). There are also Nigerian Uyaiedu Ike-Etim‘s Ìfé (2020), made through Equality Hub Production, an organisation dedicated to amplifying the voices of lesbian, bisexual and queer women, Tope Oshin’s We Don’t Live Here Anymore (2018), Aoife O’Kelly’s Walking With Shadows (2019), and more recently, Babatunde Apalowo’s All The Colours of the World Are Between Black and White (2023).

In most of Africa, where there are state-sanctioned laws that criminalise queerness, and there’s a palpable tolerance for homophobic attacks on queer Africans, it’s a daring act of bravery and opposition to organised political authority that these queer films exist. However, despite their existence in a climate that perpetuates homophobia, there is limited access to the films that provide an alternate reality for queer community members and challenge homophobic narratives. And when these listicles get published, the next question becomes, where can Africans watch these productions and how does the average queer African see themselves represented on screen? More often than not, the community has had to rely on Western films such as Sex Education, a British TV series created by Laurie Nunn about teenagers trying to understand their sexuality; God’s Own Country, written and directed by Francis Lee about a young farmer numbing his pain and frustration by engaging in drinking and casual sex until he met a boy; and Heartstopper, another British coming-of-age TV series about sexuality, created by Alice Oseman.

Successful Abroad But Denied At Home

Going through comments from The Nest Collective YouTube channel, the group that created Stories of Our Lives, one quickly confirms the unavailability and inaccessibility of these queer African films. A comment reads, “Five years later, only a handful of people have enjoyed seeing this masterpiece. For a young gay boy or girl in Kenya and all over the world, this piece of art will make all the difference as to how they see themselves.” Another reads, “Five years later, pride month is halfway gone, and still I have never seen this film.” Stories of Our Lives was created from the collected stories of Kenyas who identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and intersex. It is a five-part anthology, with each part of the film featuring stories of queer Kenyans and their daily realities.

One will find a similar thread of comments on Cypher Avenue, a YouTube channel dedicated to Geek culture and Gay/bisexual articles, movies, and interviews. The YouTube channel posted a seven-minute clip of Camara’s Dakan, a story of two young boys struggling with their romantic feelings for each other, in 2013, and some of the comments asked where one can watch the film. These comments point to the ongoing search for queer African films by not just queer Africans but by anyone trying to understand their sexuality. It also points to how different African states use geo-blocking to hinder the efforts of African filmmakers and deny access to films that capture queerness in a positive light.

It’s no wonder that African cinema has been plagued by films that present homosexuality through stereotypical and harmful lenses. In the 2010s, there was an upsurge of villainising Nigerian films that project harmful narratives about the Nigerian LGBTQ community. In Moses Ebere’s Men in Love, a gay character is presented as a homewrecker and rapist who “converted” a heterosexual male into homosexuality. In Theodore Anyanji’s Dirty Secret, a gay character is framed as a gigolo. What these films share in common is their steadfastness to follow and comply with society’s depiction of queer people in a tainted light.

There is a shared history with the stories that matter for queer representation. After screening at prestigious international film festivals and winning coveted international awards, the movies aren’t often screened or shown in the director’s home country. Camara’s Dakan premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1977, and Stories of Our Lives screened at the Berlinale and Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in 2015. To the best of my knowledge, Stories of Our Lives hasn’t screened in Africa, save for the Durban International Film Festival and Johannesburg Queer Film Festival. Similarly, Kahiu’s Rafiki, a story of two young ladies in love with each other, had its international premiere in the Un Certain Regard section at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, making it Kenya’s debut appearance. Despite this international precedence, these films were denied theatrical distribution, making it impossible to be seen by the local audience.

These filmmakers become targets for homophobic attacks. For instance, Camara, credited with Dakan (fondly remembered as the first queer African film), was constantly exposed to attacks. In different situations, Camara had to leave the screening room minutes before Dakan ended when the film was shown in Guinea. In other situations, he had to continually change hotel rooms. What might be the most traumatic of his experience was when, due to a mob attack, the filmmaker had to wistfully deny that he was the director of the film. Similar to other African countries, Guinea’s LGBT laws criminalise lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in Guinea. It’s a country where discriminatory attitudes towards LGBTQ people are tolerated.

In Nigeria, Ikpe-Etim and Pamela Adie’s Ìfé, a story that explores the dynamic of a first date between two women, was subjected to censorship by the National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB) and threatened with a jail term for promoting homosexuality in a country that gravely abhors it. In 2007, the first draft of the controversial Same Sex (Prohibition) Act was submitted to the Nigerian National Assembly. Seven years later, another draft was enacted into legislation by then President Goodluck Jonathan as the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act 2013, which made calls for imprisonment for involvement in public advocacy for queer rights, prohibiting public display of same-sex romantic relationships and adoption of children by queer Nigerians. What this law did was to further encourage homophobic Nigerians into hunting queer Nigerians and, in some cases, causing them physical harm.

Trengrove’s Inxeba/The Wound, a South African film about a relationship between two men in the context of the Xhosa initiation ritual, was met with a protest and banned from mainstream South African cinemas in 2018. Again, denying these filmmakers their right to have their films shown in their country is indicative of homophobic reactions. This digital censorship means that even when these films are available online, without access to a VPN, they cannot be viewed. Also, denying filmmakers their right to tell stories and have them distributed is an aggressive way of limiting and shutting other filmmakers from telling stories with positive queer characters. Adie, the producer of Ife, spoke with CNN about how suppressive agencies like NFVCB are to filmmakers’ creativity and said, “If there is a demand for films like Ife, and if people want it and the censor’s board does not approve, then it means they are indirectly stifling the creative powers of filmmakers. To deny a film simply because of queer characters is discrimination.” The implication of this is the continual discrimination of African filmmakers making queer films.

Is There Recourse for Queer Films in Africa?

Over time, film festivals have become a spot for indie filmmakers to attract possible distribution deals and build a loyal audience. Film festivals are also a place for screening and distribution of alternative films. For queer Africans, it can be a space for viewing queer films. While researching for this essay, I discovered two such film festivals which were dedicated to showing queer films in Africa: the Queer Kampala International Film Festival (QKIFF) and Out In Africa South African Gay and Lesbian Film Festival. Though both were discontinued, they offered a space for watching queer films on the continent. Though a film festival, it had political motives, one of which was pushing for legal reforms by expanding the network of LGBTIQ advocates, supporters and activists who can lobby the relevant authorities and stakeholders.

QKIFF attracted documentaries about raising queer children and conversion therapy, as well as coming-of-age dramas and edgy romances. Talking with Vice in 2016, Kamoga Hassan, one of Uganda’s committed core LGBTQ activists and lead organiser of QKIFF, mentioned the incredible importance of the festival. “Gay people in Uganda don’t have their own media space. Most of the local media outlets spread antigay propaganda. We want the festival to become that space where we can invite people who are gay but also people from outside the community who want to meet us and understand us,” Hassan said. These queer film festivals and films, though targeted by homophobic crowds, have been influential in creating a space for queer audiences to embrace their humanity, watch themselves on screen and, importantly, have difficult conversations.

African International Film Festival (AFRIFF), Nigeria’s biggest film festival, has somewhat presented itself as an inclusive space for queer films. In 2020, the festival accepted Ezeigwe’s Country Love, a tale of romance, queerness, memory, and redefining the idea of home, while in 2023, Babatunde Apalowo’s All The Colours of the World Are Between Black and White and Chinanzaekpere Chukwu‘s short film Ti E Nbo, a story of a young boy’s struggling with his feeling for his male friend, screened at the festival. Having been accepted by AFRIFF, these films that push positive narratives about the LGBTQ community inspire the question: If AFRIFF is accepting these films, why are they not publicly acknowledged in Nigeria? The answer is simple: AFRIFF’s international posture makes it a consecrated spot removed from Nigeria and the censor officials’ scrutinising gaze.

As history will show, these film festivals aren’t free from state-sanctioned policing and discrimination. QKIFF was raided, but the festival’s organisers successfully held it in secret. The festival organisers used various measures to prevent police from clamping down on the festival, including security screening of attendees, and keeping the venues secret and mobile. Encouragingly, the LGBTIQ community, supporters, and sympathisers religiously followed the different venues, attracting a turn-up of 800 visitors within a space of three days. QKIFF’s success is reminiscent of Rafiki’s. Upon winning a court case against the Kenyan Film Classification Board (KFCB) that banned Rafiki for having an optimistic ending for its queer characters, the film was allowed to show in the country’s cinema for seven days in 2018. Regardless of the limited theatrical distribution, Rafiki became Kenya’s second-highest-grossing film.

Inxeba, Rafiki, Dakan, and other queer African films’ exhibition history illustrates the complex and contradictory space inhabited by queer cinema, films, and filmmakers on the African continent, where state-sanctioned homophobia largely remains the norm. Unfazed by the often religious and politically motivated onslaught against sexual expression, queer films and filmmakers continue to thrive. Despite how gloomy the situation might appear for queer African cinema and film festivals, few films are accessible to watch without hurdles.

A glimmer of hope for queer representation, Stories of Our Lives is available for rent on Vimeo. Senegalese’s Joseph Gaï Ramaka‘s Karmen Geï, one of the pioneering queer African films, is on YouTube. Wapah Ezeigwe’s Country Love and Ikpe-Etim’s Ìfé are available on Cinelogue, an online global streaming platform with a €8 (N12,900) monthly subscription. Inxeba (The Wound) is available on Prime Video, while Rafiki is on Netflix. Additionally, Olive Nwosu‘s Egúngún (Masquerade) is on Vimeo. Unmindful of targeted homophobic attacks on the queer community and queer African cinema, the community and film production still thrives.

Seyi Lasisi is a Nigerian creative with an obsessive interest in Nigerian and African films as an art form. His film criticism aspires to engage the subtle and apparent politics, sentiments, and opinions of the filmmaker to see how they align with reality. He tweets @SeyiVortex. Email: seyi.lasisi@afrocritik.com.