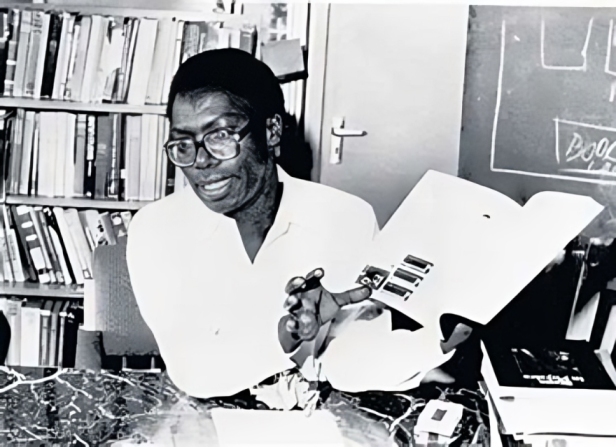

Jonathan Kariara became foundational not by speaking the loudest, but by enabling others, mentoring, editing, insisting on seriousness, and stepping back.

By Frank Njugi

Jonathan Kariara is a name we invoke in Kenya more than we read. He circulates in the Kenyan literary imagination as a curricular fixture. You find the name on an old random poem here, a footnote there, a respectful pause in the syllabus before a literature class or workshop moves on to louder, more easily recognisable figures. He also exists in the present tense primarily as institutional memory, anthologised, summarised, and embalmed, hovering somewhere between Okot p’Bitek’s performative certainty and the declarative weight of a nationalist canon.

I first encountered Kariara through admiration passed hand to hand. Years ago, as I was finding my footing in Kenyan poetry, Nduta Waweru, perhaps my favourite Kenyan poet, introduced me to Kariara’s work as her own primary influence. It was offered almost in passing, as if pointing to a well-known landmark everyone somehow kept missing. That casualness felt instructive still. Here was a poet who seemed to be everywhere and nowhere at once: foundational, yes, but strangely unpossessable.

This is how Kariara most often appears to us. Reduced to Grass Will Grow, his most famous work, flattened into the Makerere University mythos, and absorbed into a generalised idea of an “African voice”. So, the problem is not that Kariara has not been remembered, but that he has been remembered too narrowly. His legacy has also been compressed by a trifecta of cultural pressures. This is because there is pedagogical convenience, which turns Grass Will Grow into a lesson on endurance that can be easily examined and safely concluded.

There is post-independence urgency, which recruits him as a foundational Kenyan voice even when his poems resist the certainties such a role demands. And there is the enduring shorthand of the “Makerere School”, a label that emphasises formal English inheritance while muting the more intimate, disruptive tensions in his work.

Yet Kariara’s career resists the logic of dominance. We can all discern he did not overwhelm the field with volume, nor did he declare himself a spokesman. If anything, he practised a studied refusal of that role. Jonathan Kariara became foundational not by speaking the loudest, but by enabling others, by mentoring, editing, insisting on seriousness, and stepping back. He was a poet said to have “spoken for the land” without ever claiming to own its narrative.

The Makerere School of English in the mid 20th century is often embalmed as a golden age — as an origin myth populated by future giants, glowing with inevitability. In the early 1960s, it was a workshop and site of instruction, and experiment, and where the idea of East African literature was still provisional, still fragile enough to fail.

Within this space, Jonathan Kariara neglected the spectacle of his own authorship. It appears he understood something that perhaps other figures missed, which was that a national literature does not come into being through brilliance alone. It requires infrastructure, journals, editors, standards, and, above all, the courage to say this belongs here. Kariara seemed concerned with making sure the room itself would hold.

His legacy at Makerere is defined by a form of labour that rarely photographs well but endures. The most emblematic example remains his encounter with a young Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who approached him with a short story that would later be known as “Mugumo”. The story goes that in 1960, Ngũgĩ (then a shy freshman) approached Kariara, then an older and more established student writer, to critique a short story he had written named “The Fig Tree” (later published as the said “Mugumo”). Ngũgĩ felt encouraged to write more when Kariara thought the story was the work of D.H. Lawrence.

The story was published at Penpoint, the literary magazine of the English Department at Makerere University, and a journal with which Kariara was closely involved. With the curation at Penpoint, African writing had begun ceasing to be an abstract argument staged in overseas journals and metropolitan conferences and became a local practice, as Kariara, as a curator, understood that the elusive “African voice” would be summoned through the disciplined assembly of poems and stories, and the nerve it takes to let them stand.

So it is fair to conclude that one of Jonathan Kariara’s deepest influences was editorial, an architectonic power that shaped not just individual careers like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s, but the very texture of East African letters. Later on at the East African Literature Bureau and later as manager of Oxford University Press in Nairobi, Kariara exercised editing as a form of authority in a literary age thick with post-independence urgency.

Research of past documentation tells you his editorial standards were famously unforgiving as he had little patience for what might be called the “easy win”— the poem buoyed by sentiment, or the story propped up by folkloric shorthand, mistaking recognisability for depth. What he wanted was substance, the real yam beneath the leaves, with him demanding specificity over trope, and precision over generality. A vaguely “African” voice was not enough as the writing had to carry the grit of lived reality, and the pressure of place and the discomfort of truth.

This commitment was clearer than in Zuka: A Journal of East African Creative Writing, a prestigious literary magazine launched in 1967 in Nairobi. It played a role in shaping the region’s post-independence literary landscape. Kariara founded and edited the journal.

Under Jonathan Kariara’s guidance, it is said Zuka was a sanctuary for depth, treating editing itself as cultural labour, a form of nation-building that unfolded slowly, through revision and selection. The journal cultivated seriousness, and Zuka appears to have published work that balanced high modernist discipline with communal sensibility, refusing to collapse one into the other. Kariara’s own published literary work had been a demonstration of such standards and ethos as the writing that was formally alert and unwilling to trade complexity for applause.

“Grass Will Grow”, itself, is a poem so frequently taught to us as an anthem of resilience that its more disturbing intelligence is often smoothed away. Read closely, the poem is not about hope only. It is about continuance without mercy as well. The famous refrain—for grass will grow—functions as a fact, delivered with almost scientific coldness. Whether a child is buried, a homestead burned, or a life dismantled by violence, the grass responds in exactly the same way. It grows. Not because justice has been served or grief resolved, but because growth is what it does. This indifference is also the poem’s subject.

A Leopard Lives in a Muu Tree, his other famous poem, carries this logic inward, from open land to domestic space. The leopard is a constant presence, watching, waiting, lodged in the branches above daily life. The homestead becomes a site of permanent tension, a place where safety is provisional, and threat is intimate.

What is striking here is how rarely violence is performed outright. Jonathan Kariara prefers implication. Broken fences, mottled offspring, the uneasy, almost manic vitality of the wives— these are the poem’s clues. The danger is not foreign or external, but from “one-from-the-same-womb.” The leopard has often been read as a symbol of imperial domination, and the reading holds. But Kariara’s imagination is more unsettling than allegory allows. The predator is also domestic, internal and intimate, proof that the land he “spoke for” was never an innocent terrain but a landscape already compromised by proximity similarly.

So what Kariara’s poetry ultimately reveals as well is a defiance of the easy binaries that structured his era. In a literary moment when Africanness was often signalled through chant, repetition, rhythmic insistence, and the theatrical retrieval of orality, Kariara took the opposite route. It seems he declined the performance. His work suggested, stubbornly, that African experience did not require acoustic proof.

Where others leaned into a performative orality, deploying cadence to announce cultural legitimacy, Kariara’s English remained formal, careful, even austere. He did not write as though the language needed to be apologised for or theatrically indigenised. Nor did he treat it as a neutral inheritance. Instead, he used English with the precision of someone who understood its weight and limits, shaping it into an instrument for mapping silence, fracture, and interior pressure. So we can say his Western education at Makerere did not produce mimicry, but if anything, it sharpened his restraint.

Jonathan Kariara’s legacy does not end at the bookshelf, though, with his curation and written work. It moves laterally, into rooms where art was argued over, rehearsed, tested, and made communal. His work as one of the original six founders of Paa ya Paa Art Centre, an arts space most often described as the ‘first indigenous African art gallery in Kenya, offers perhaps the evidence of his belief in ecosystems over individual genius.

Paa ya Paa gathered painters, sculptors, musicians, actors, and writers into a single, porous space, insisting that African creativity required cross-pollination rather than siloed excellence and Kariara’s hand in this aligned perfectly with the editorial philosophy he practiced elsewhere which was to create conditions, uphold standards, then step aside, so that the work, not the personality, has to carry the room.

All in all, Jonathan Kariara’s legacy is something you trip over every time you read serious East African writing from an era, but the tragedy—and the convenience—of literary history is that it likes its figures shrink-wrapped into single works. Too often, his reputation is reduced to the singular fame of Grass Will Grow, but the poem is merely a visible tip of a far larger edifice. Kariara’s most enduring work lies in the invisible labour of stabilisation, standard-setting with both the said poetry and his curation, and insistence on rigour.

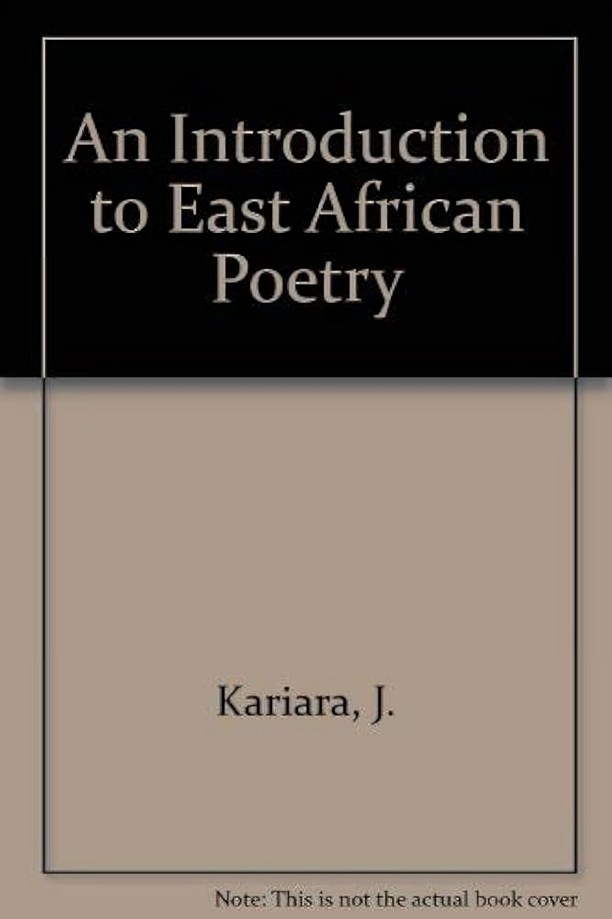

Through An Introduction to East African Poetry ( 1976), Kariara curated a blueprint for what East African literature could be: the poems in the book are precise and intellectually sovereign, exploring themes relevant to the East African experience at the time of publication. His eye for craft, his insistence on specificity, and his ethical concern for truth set a tone that continues to shape us, poetry writers decades later.

So it is my conclusion that his influence operates along three intersecting lines. First, the writers he enabled, from Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o to generations of Makerere students, represent his primary output: the success of others. Second, the standards he insisted upon refused the shortcuts of post-colonial rhetoric, ensuring that Kenyan poetry carried a density and moral weight capable of surviving the fluctuations of political and cultural fashion. Third, the institutions he strengthened—from Oxford University Press in Nairobi to the Paa ya Paa Art Centre—embody his commitment to ecosystems over egos, spaces where craft could flourish beyond individual ambition.

Jonathan Kariara was foundational not because he dominated the field, but because he steadied it. He understood that the permanence of literature is built not on volume or performance, but on care, rigour, and the patience to make spaces where others can speak and be heard. In 2026, as retrospectives revisit his life, it is this architecture of influence that proves his work both indispensable and enduring.

Frank Njũgĩ, an award-winning Kenyan writer, culture journalist, and critic, has written on the East African and African culture scene for platforms such as Debunk Media, Republic Journal, Sinema Focus, Culture Africa, Drummr Africa, The Elephant, Wakilisha Africa, The Moveee, Africa in Dialogue, Afrocritik, and others.