A keen observer would notice that much of Shegun Oseh’s work is the conscious artistic reconfiguration of photography.

By Chimezie Chika

For some years multivalent visual artist, Shegun Oseh, has used and mixed artistic mediums across photography, digital art, and music to create an arresting array of works that upends the conventional imagination in its bid to offer an intense illumination of identity, cultural heritage, and emotional currents.

Shegun Oseh’s work is characterised by deliberately doctoring his photography into pixelated frames or editing a base form of photography into works of abstract digital art. One work in Oseh’s oeuvre, “Sounds of my Forefathers”, featured in a group exhibition titled “Abstraction: The Energy Within” at the Fox Yard Gallery in the UK, merges his interests and techniques.

The resulting work superimposes ten different photographs of drums and, in the final product, presents an abstract colour blending of traditional Yoruba musical instruments, including a full set of five talking drums. And yes, the original ten images are screened so that what we see before appears to have taken fewer photographs to merge.

A keen observer would however notice that much of Shegun Oseh’s work is the conscious artistic reconfiguration of photography. Nothing here is left as it is. The artist stretches the activities of the darkroom into abstract monochrome pixels. His making of photographs seems to move in the opposite direction of conventional photography development.

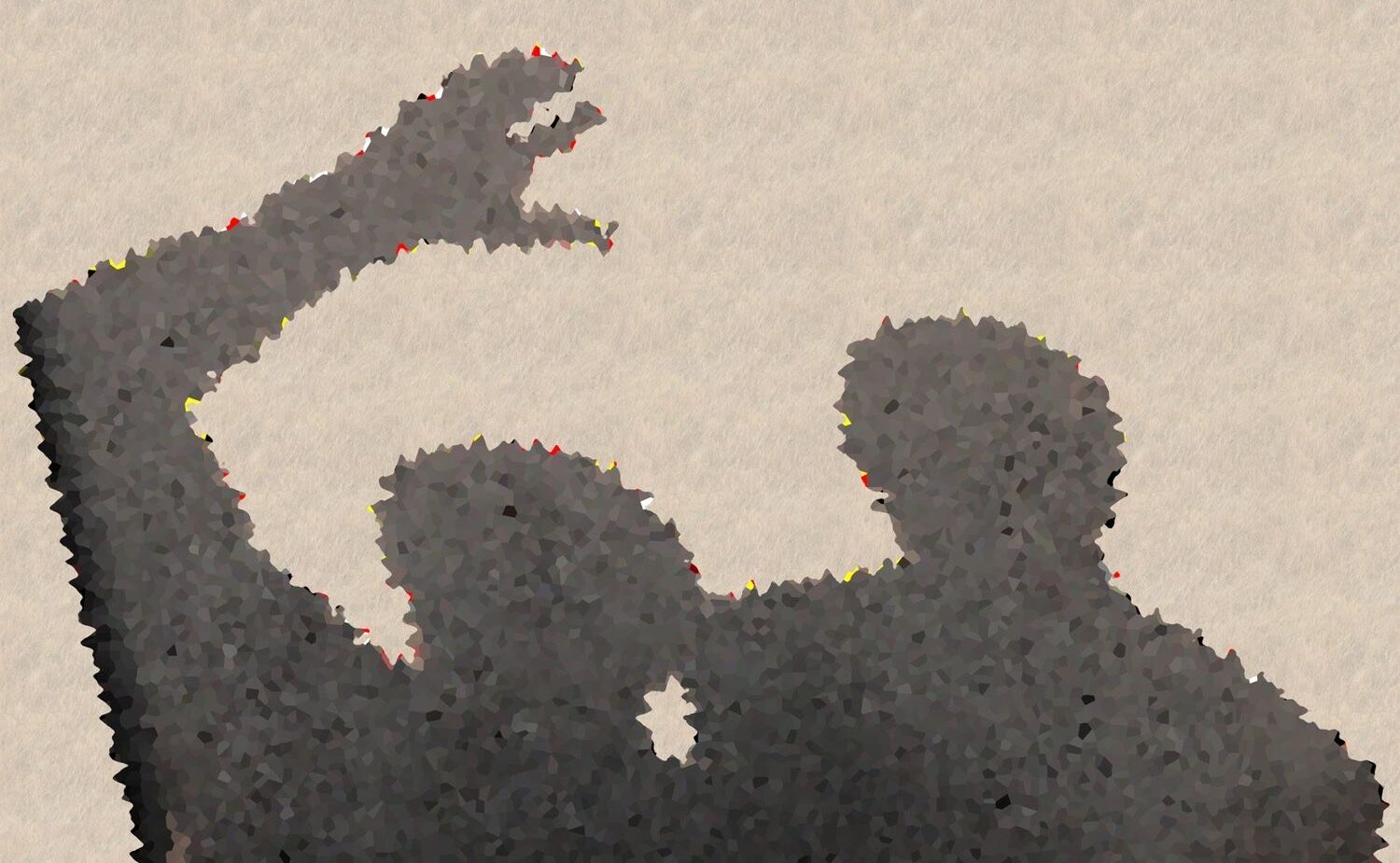

Several works leave us with the feel or sight of more technical investments than are actually used. While they appear to be pixelated photographs of human shadows, one can easily mistake these works to be pencil drawings on canvas or work created through increasingly popular techniques such as fire and smoke painting—thus, in that sense, his work may be said to have the deliberate effect of a literal smokescreen.

An art series by Shegun Oseh focused on human limbs typifies this. As visual art goes, the work here pushes the boundaries of conjecture, and their simple non-attributive titling leaves further space for the viewer’s imagination. “A Foot Touching Another in Greeting” evokes something more ghostlike; “Hands Cradling the Head”, obviously taken in the shadow of the sun, is given spooky connotations by its serrated edges; The same can be said of “Hands Slipping Way”, whose meaning is more melancholy.

While these images appear singularly made to turn human emotions into abstract forms—if we consider that limbs are used as expressive tools of the human anatomy, especially when we gesticulate—two of them, “Hands Entwined in Prayer” and “A Raised Hand in Greeting Left Unanswered”, not only plumbs the imagination with more metonymic signifiers but evokes daily life. Thus we have two people praying and a greeting that went unanswered.

What, however, do we see within the boundaries of these images? We see two figures, for sure, and sticking hands or what appears to be hands. But, with these simplified abstractions, it is enough to allow viewers to read their sight-specific meanings into the images.

From these last two marginally lively images, a more lively monochrome emerges. Shegun Oseh titles it “Family Time”. On the surface “Family Time” appears to have more kinship with the images discussed thus far, in its pixelated blur rings of the boundaries between the real and the imagined, the figurative and the abstract, the fully outlined and the suggestively metonymic. Beyond the blurry background of “Family Time”, our attention is mainly drawn to a double door.

In Polaroid blur, the clear outlines of glass: one open, the other closed. Within the frame of the open door, an indeterminate figure is sitting on a sofa of indeterminate colour in a bright mostly-white room. Another sofa in the room appears to be of milkish colour. Behind it is another door, made of white wood.

On the ceiling, three simple chandeliers. On the far right, almost completely cut off from the frame, is a man’s right hand and shoulder. The open glass door has half a reflection of what is inside. It is a miracle how much Shegun Oseh can fit into this picture, so that the viewer sees and feels life going on within it in a fulsome way.

Another image in this vein, by which I mean there is activity, is “Love Under the Umbrella”. Unlike the previous one, this image is a negative turned into Oseh’s blurry pixels. There are two barely visible figures almost entirely screened by the dark background.

By their length, positionings, and outlines, we know it is a man and woman close together. There is an umbrella over them, possibly held by the man. As is the case with negatives, the umbrella is light and much of the humans are shrouded in darkness. But we can assume, by synecdochal association, what is going on here. Doubtless, love and other related emotions.

In the world of Shegun Oseh’s pixelated monochromes and blurry negatives, there are only two images, thus far, that are made in colour.

Colour, however, is the only thing that separates them from the rest. In short, an image such as “A Stroll in the Beach” takes its smokescreen of pixels to its most extreme—that is, to the most basic pixel in photography development. Thus what we are left with are technicolour blurs of yellow, blue, green, orange, and a host of other colours in between, from which we can assume the outlines of the sky, sea, beach, and a strolling figure.

Why has Oseh chosen to make this part of his work a subject of intense investigation into meaning and implication? Why make these smokescreen images? One justification is that he wants to bring his photography and visual art into one canvas. But there is more. He often talks about creativity and pushing the boundaries of visual storytelling. On that note, it will be more interesting to see the direction in which his work is going.

Chimezie Chika is a staff writer at Afrocritik. His short stories and essays have appeared in or forthcoming from, amongst other places, The Weganda Review, The Republic, Terrain.org, Isele Magazine, Lolwe, Fahmidan Journal, Efiko Magazine, Dappled Things, and Channel Magazine. He is the fiction editor of Ngiga Review. His interests range from culture, history, to art, literature, and the environment. You can find him on X @chimeziechika1