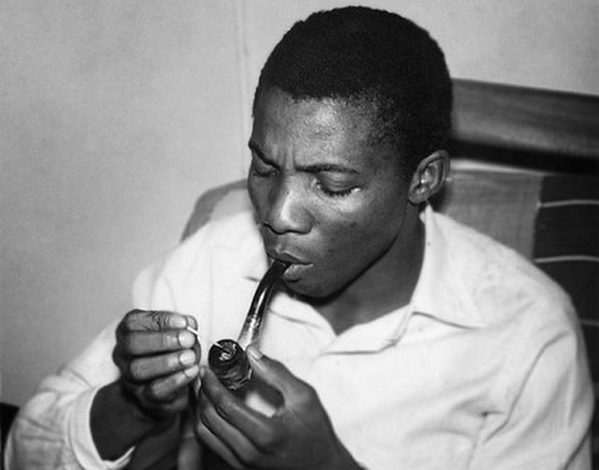

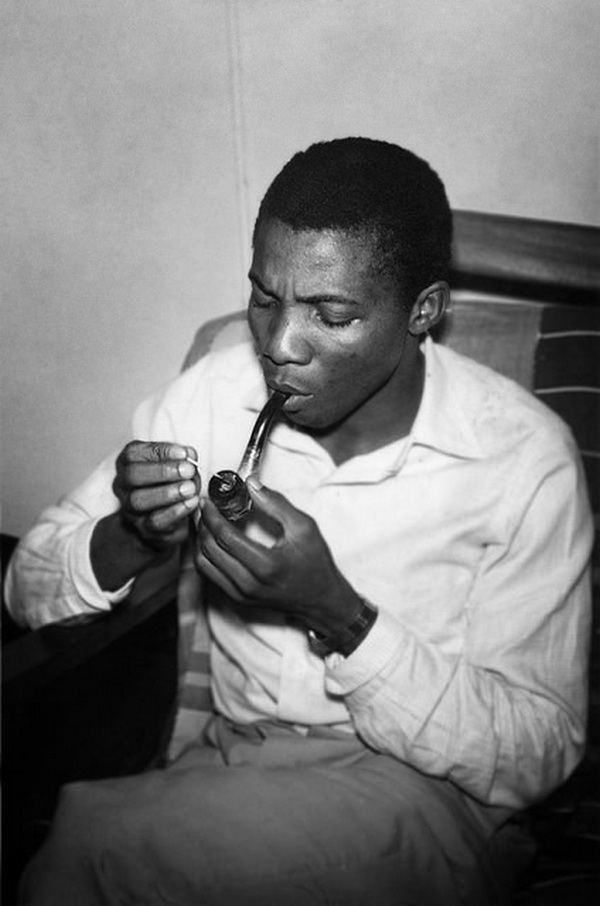

Christopher Okigbo was likewise a remarkable conversationalist. [In his interviews], he gave precise answers that show how much thought he had given to the issues he commented on.

By Ernest Jésùyẹmí

Christopher Okigbo had been many things by the time he died in 1967. At Government College, Umahia, he was (as Bernth Lindfors tagged him) a “jock”: cricket, soccer, boxing, the man excelled at each one. He played music. After graduating with a Third Class in Classics from University College, Ibadan (now University of Ibadan), he taught Latin at Fiditi Grammar School, where he encouraged sportsmanship among his students. Before Fiditi, he had a stint in government (as a personal secretary to a Minister of Information). He worked for the Cambridge University Press. When the war began, he went to fight for Biafra and died as a soldier.

(Ah, yes: he also edited Transition.)

Ultimately, though, he was a poet. He told Marjory Whitelaw in 1965, “There wasn’t a stage when I decided that I definitely wished to be a poet; there was a stage when I found out that I couldn’t be anything else.” It is as a poet that he made his mark and that he will continue to be remembered.

Christopher Okigbo was, likewise, a remarkable conversationalist. The interviews known to me are the one with Whitelaw, others with Lewis Nkosi (1962), with Dennis Duerden (1963), with Robert Serumaga (1965), and one with Ivan van Sertima. The first appeared in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature in 1970; the three in the middle were published in African Writers Talking (1972), edited by Dennis Duerden and Cosmo Pieterse. The last one was printed for the first time in 2011 in a critical edition by Chukwuma Azuonye. Okigbo only rambles when talking about his Labyrinths; otherwise, he gave precise answers that show how much thought he had given to the issues he commented on.

1. The Self and Belonging

Christopher Okigbo’s thoughts on identity, on African-ness and universality, were very clear and very complex. When Whitelaw asked him if he was “an African poet”, he answered no. “There is no such thing as a poet trying to express African-ness. Such a thing doesn’t exist. A poet expresses himself.”

Okigbo saw Negritude as it ought to be seen: as “a particular type of poetry . . . platform poetry”. He did his classification of poems in poetry-terms, not the other way around. What people like Leopold Senghor did—their mistake—was that they assumed that it is possible for a single type of poetry to represent “African poetry”. Much of the discussions around the language for African literature and those by the de-colonialist academics (Chiweizu et al) arose out of this confusion of two different kinds of things: a type of poetry can never represent a continental or national literature.

Christopher Okigbo understood the matter even better than I think Soyinka did. When Soyinka says “The tiger does not proclaim his Tigritude, he pounces”, he took the assumption underlying Negritude as valid when it was not. Okigbo set things straight: post-colonial French poetry was not any more African than what he and his Anglophone contemporaries were making. Poetry transcends its types.

Moreover, it was futile to talk of “African-ness”. Okigbo argues (as J. P. Clark-Bekederemo also did) that Negritude, for instance, was inevitable for Francophone poets because of their history, the policy of assimilation, which put a strain on their “integration” into their own background. Thus: “the French poet finds himself uprooted and casting about for his lost roots.” Every poet is always “casting about”: “We are trying to cast about for words; whether the words are in Ibo or English or French is in fact immaterial.” But the French poet, because of his condition, casts about for words as a way to form a root for himself.

If the historical contexts are different for a Senegalese and a Nigerian, a South African and a Ghanaian, how then can they be expected to produce a representative kind of poetry?

Christopher Okigbo avoided holding onto a pan-Africanist sentiment because it was vague and unprofitable, as he saw it. To get his drift more clearly, we have to pay attention to what he meant by self when he said “a poet expresses himself”:

“So when I talk of the self, I mean my various selves, because the self is made up of various elements which do not always combine happily. And when I talk of looking inward to myself, I mean turning inward to examine myselves.”

He goes on to talk about the household gods in his village, at Ojoto: Ikenga and Udo. He was not there to offer sacrifices, but he believed that when his family gave offerings to the gods he was a part of the affair. “And I feel, you know, that we still belong to these things. We cannot get away from them.”

You can belong to something you are in proximity to; the closer you are to a thing, the more possible belonging is. Africa is too large, “African” too impossible a concept to feel intimacy for in any real sense. But Ojoto, U.C.I., Ibadan, Nsukka, “everything that has gone to make me what I am”—these are all inescapable. And every poet has a responsibility to such things.

2. A Small Digression

I should make a point here about contemporary Nigerian poetry. A common misreading of my essay on the subject has been the assumption by other writers that I was making similar arguments as Chiweizu. Yinka Adetu drew the comparison in “Revisiting the Soyinka-Bolekaja Debate”. Kanyinsola Olorunnisola made a similar point in his response. After calling me a Nativist, he writes: “For literary Nativists, including the influential Obi Wali, writing must prioritise culturally locatable and indigenous linguistic elements.”

“Prioritise” is the word to pin. It shows how many people read their own assumptions into what you write. Like Okigbo, I do not believe (and never argued) that cultural signifiers should be “prioritised” in a poem. The poem by J. K. Anowe (“Tender Crow’s Feet”) that I discussed and praised at length includes no such signifier. Here is what I say about that poem and others: “As in Anowe and [O-Jeremiah] Agbaakin, it is something about the discipline, the eccentricity of their poems” that makes them Nigerian. In “Logan [February], it is this fiery, casual yet meticulous sensibility”.

The mention of signifiers was only one of many types of things that might make a poem Nigerian, and they are offered tentatively: “A Nigerian poem . . . may simply include the word ‘tueh’.”

Okigbo differs (and I differ) from both the “Nomadists” and “Nativists” (Olorunnisola’s typologies). The first group cannot sustain a national literature; those who claim that position will produce work that is indebted to nothing. They will write without any sense that, as Okigbo said, “they belong to” certain things (i.e., their country and its history) that they “cannot get away from”. The Nativists believe that the background of the poet should be the defining thing about whether we consider their work good or bad. Both positions are extreme and are fatal to art.

3. Have No Commitments

It was of the greatest importance to Christopher Okigbo that a poet be free of any superficial obligations. He was resolutely opposed to anything that wanted to be “prioritised” over the work of creation itself. As he said to Marjory, “I don’t think that I like writing that is ‘committed’. I think it is very cheap. I think it is the easy way of doing it.”

A poet, once he starts to be “committed” (to a cause, a political ideology, to Nigerian-ness—which, again, should be the by-product and not the driving motive of making serious poetry), starts losing his creative power. His capacity for invention comes under constraints. A poet functions best when he is free. Even more, language itself is a sufficient burden (and involved with it are several others); the poet, in assuming a position that he feels obligated to, will cripple his own hand.

“I think it is the easy way”: via facilis. Poets who concern themselves with outer things are looking for substitutes for what Okigbo called “the agony of composition”. They do so because they lack the courage to face that “agony”.

Invited to Kano to give a lecture to schoolchildren, Okigbo had no speech and chose to read them a few poems—“and the children burst into tears.” He says, “I felt that . . . at least they had had experience of the agony I had gone through . . . You know the process of writing that particular poem I read to them had been agonising.”

The distaste he had for unearned ease was another reason why he was not a big fan of Negritude poetry. South African writer and journalist Lewis Nkosi asked him why he said “vile things” about much of French poetry at the Kampala Conference on African Writers, Makerere. Christopher Okigbo said: “when you’ve read a lot of it you just hit the whole pattern, you begin to have the feeling… that it is just like working a machine or, if you like, working a duplicating machine, you think it is easy to do.”

A similar statement can be made about Nigerian poetry today, which is partly because the ghost of Negritude has arisen; but now it is to Derek Walcott that Nigerian poets have turned (I am not suggesting that Walcott was a Negritude poet, though his poetry definitely is tinctured). Senghor, of course, is still alive in Romeo Oriogun. Perhaps because in the Japa era poets are looking to form new roots for themselves.

4. On Craft

Christopher Okigbo belonged to the Mbari club in Ibadan and served as an editor on Black Orpheus before he left to join Transition as West African Editor in 1963. His view of the magazine was very critical. Ulli Beier, he felt, was patronising the “black mystique” instead of seeking out and printing good art.

Beier’s love for the exotic, premature, and unfinished was unremitting. It meant that he would publish work that was incredibly flawed on a craft level, so long as it felt Black. Anyone who has gone through the virtual issues of Black Orpheus archived by Olongo Africa would know how justified Christopher Okigbo’s criticism was. (Beier published a selection of drawings or paintings by imprisoned men who had no formal training, work that looked as though made by two-year-olds, and claimed that these were great.)

To Christopher Okigbo, who was a skilled craftsman, craft cannot be sidelined in making art. A painter must have “a sense of rhythm”. A work of art that is just constructed the right way will not stir the heart, because it is lacking in feeling—art is feeling (in Okigbo’s view). Yes. But the feeling cannot be genuine or lasting unless it is well-made. It matters very little whether a work is culturally significant, whether it is an experiment, whether it bears witness . . . is it beautiful?

Okigbo told Duerden, commenting on the paintings included in Black Orpheus No 12: “I just thought those reproductions were ugly”.

It should be noted that the first generation of Nigerian writers had a different conception of community from the one that is now orthodox. They criticised each other’s work very sharply. Okigbo said to Nkosi, who asked if he and his friends “approve of each other’s works”, “God forbid! Why should we? How can we approve of each other’s works? I mean . . . I am one of [J. P. Clark-Bekederemo’s] severe critics, and I think he is one of my greatest adversaries.”

(There was an audio at the British Library—not accessible at the moment—in which Soyinka offers a scalding criticism of a play by Athol Fugard, the South African playwright. Their generation took serious criticism as an act of love.)

5.

Much remains to be explored in Christopher Okigbo’s interviews. In a sense, these notes are meant to be gestures toward an exploration. For instance, his idea against intentionality in a work of art (“I can never really say what the intention [of a poem] is”, in the interview with Van Sertima), which sits so close to the Scottish poet W. S. Graham’s (“some intention risen up out of nothing”). But the matter demands a separate essay. One would break a leg if one tried to run the race at this moment.

One last word from the weaverbird is necessary. To Nkosi: “I mean if I have nothing to say, I just keep translating—keep playing with work because I have seen that a poet, apart from being a writer, is also a technician . . . you have to keep practising.”

The last five words, I hold close to my heart; but it should be clear that practice here does not mean writing; it means labouring for fecundity, an active waiting for it.

And when it comes and you make good art and no one is interested in taking it, or people do not recognise what you have brought about? Remember: “I don’t care for applause.” It will save you many headaches and sleepless nights.

Ernest Jésùyẹmí is the author of A Pocket of Genesis (Variant Lit, 2023). His work has appeared in AGNI, The Sun, Poetry London, The Republic, and Mooncalves: An Anthology of Weird Fiction. He holds a BA in history and international studies from Lagos State University, Nigeria, and is the poetry editor of EfikoMag.