To question prayer in Nigeria is to commit spiritual arrogance. Rational inquiry reads as rebellion. The idea that human effort alone produces results carries cultural suspicion; removing God from the equation means tempting disaster.

By Olumuyiwa Aderemi

It’s 5 am on December 1st, 2007; Harmattan season, when the Sahara Desert exhales across West Africa, cracking lips, shrivelling skin, turning body cream into currency. I was deep in a dream about the Christmas chicken I would be eating 2 weeks into the festive month and the Xbox360 console I’d been promised if my report card came back excellent. I’d aced my midterms. The gift was practically mine. I was already planning which friends I’d invite over to christen it, but something yanked me out of this pleasure.

“WAKE UP. IT’S TIME FOR MORNING DEVOTION”, the hostel warden’s voice, megaphoned and unforgiving, cut through the dormitory for the Christian students. Before I could get a bearing of my surroundings, the Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer, rose from the mosque over 100 feet away from the dormitory, somehow louder, more insistent. Though I wasn’t a Muslim, I was furious. Two competing soundtracks to sunrise. Two different calls to the same posture: prayer.

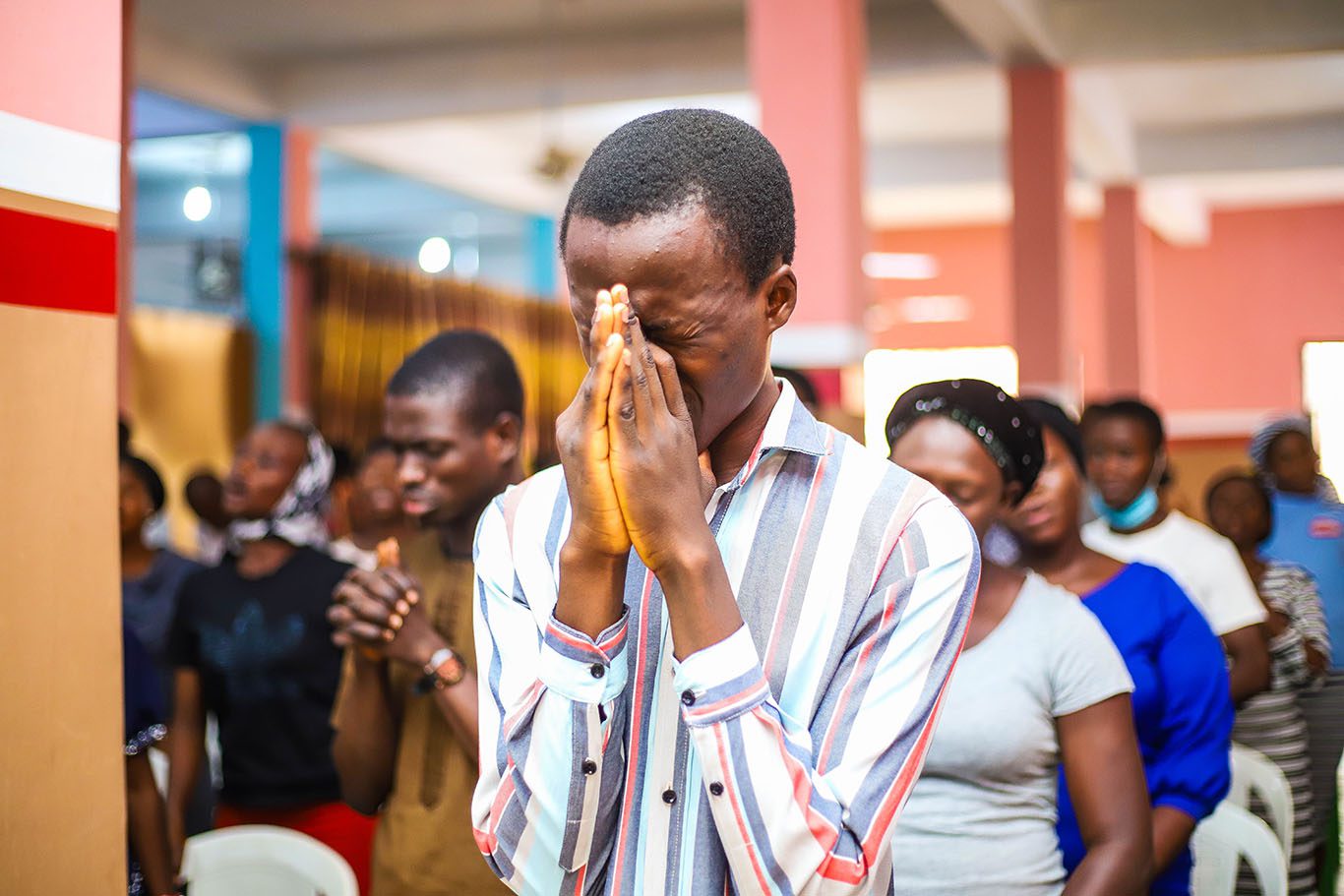

Fifteen minutes into morning devotion, we’d started binding and casting out evil spirits of forgetfulness, stealing, “bad boy behaviour”, and truancy, afflictions I didn’t know were disturbing me but were apparently obvious to the all-seeing eyes of the hostel warden. I looked around and saw that more than half the students that morning were taking part in this ritual through sleepy eyes, and the student the hostel warden had chosen to lead the praise portion was more or less ministering to himself. While this went on, I wondered: Why do we pray so much in Nigeria?

I’ve never left the country, but from what I’ve read online and seen in Hollywood films, Nigerians, Africans really, pray far more than people in the West. Yet, we consistently face socio-economic hardship. Every day, someone kills someone else. Men defile their daughters or someone else’s. Women are preaching financial stability above life itself. Politicians embezzle funds. A snake is thinking of how to take a bite out of the national treasury. Everything feels dog-eat-dog here. So what exactly do our prayers mean?

Eighteen years after that fateful December morning and after attending Christ Apostolic Church (CAC), Mountain of Fire and Miracle Ministries (MFM), Redeemed Christian Church of God and interacting with a lot of religious individuals, be it Christian or Muslim, I believe the Nigerian prayer culture is about more than faith. It’s about survival. It’s our complex response to historical trauma, systemic failure and a collective longing for control in a world that gives us so little. Prayer has become a coping system, political language, a survival instinct and a social performance, and maybe this is why we pray so much in this country. But how did we get this way? What are the reasons for this?

Historically, in Nigeria, religion has always been a part of daily life. Long before Christianity and Islam made their way to the continent, many African societies already believed in God, divinities, ancestors, and the unseen forces that governed existence. Faith wasn’t something separate from life; it was life itself. Every act, from birth to death, carried some spiritual significance. This deep spiritual devotion also shaped how Africans and their cosmology understood good and evil.

Traditional African religion wasn’t about prayer as we know it now; it was all about ritual and reverence, a way of communicating with spiritual forces whose full nature remained beyond human understanding. Then Islam arrived in the 11th century, particularly in Northern Nigeria, and brought with it five daily prayers as non-negotiable proof of faith. Prayer became rhythm, a heartbeat marking each day for every practitioner.

Christianity, as far back as the 14th century, made its way with colonialism, and the missionaries reframed everything. Prayer became a conversation with God, a direct line to access His power, a way to petition for divine intervention. But more than that, Christianity sanctified suffering as noble and sold prayer as the only weapon left to the powerless. The “prayer warrior” phenomenon was born.

What followed the introduction of these two religions was a flattening of indigenous understandings of spiritual communication via prayer. Then independence came in 1960, and the colonial masters left, and Nigeria lurched through military coup after military coup, searching for footing on ground that kept shifting. The churches and mosques grew rapidly, not despite the chaos but because of it. They became alternative structures offering hope where the country’s government offered corruption, providing governance where the state provided only violence and neglect. “God will do it” became the inherited resignation of a generation. And prayer? It became necessary for survival itself, a continuity of coping mechanisms passed down like heirlooms. When everything else fails, you pray.

Another reason why prayer is so popular with Nigerians is that it is seen as an emotional infrastructure in a society where control and stability barely exist. Nigeria’s unemployment rate climbs ever so often. Inflation devours savings. Steady income is elusive, and bank loans are nearly impossible to obtain. In this precarity, prayer becomes catharsis, a way to metabolise anxiety, process pain, and renew hope. It functions as cultural shorthand for what anyone might seek with therapy: emotional ventilation, mental reconstruction, and the chance to be heard.

When institutions fail systematically—healthcare collapses, education deteriorates, justice systems ignore the vulnerable—prayer becomes a way to reclaim agency. “I can still appeal to God, and he will fight my oppressors” transforms into an incantation by Nigerians to reassert their power as persons who are powerless, and the lack of good governance has left them in a financial, mental, and social vacuum. Prayer doesn’t just fill that space. It sanctifies it.

This cultural reason for Nigeria’s vigorous prayer culture is further reinforced by the prosperity gospel. Capitalist aspirations are deep-seated in Nigeria. The average person calculates their life in six-figure salaries: what they’d do with the money, who they become, how everything would change. But when the government fails, and the economy offers few legitimate paths to wealth, prayer becomes the strategy. Not spiritual practice but transaction.

The pattern repeats everywhere: pray to be chosen after your job interview, pray for your visa to be approved, pray for your bid to win a contract, pray for the business deal. Money needs prayer. Survival needs prayer. And while the intersection of spiritual and material life holds real meaning for many, there’s a darker reading here – a society that has substituted prayer for action. Hard work, consistency and tangible effort get sacrificed on the altar of divine intervention. What survives this is a population that looks less faithful than paralysed, outsourcing agency to God because taking control feels impossible, or perhaps too dangerous.

As conservative people, Nigerians place a premium on gestures of piety. Males must prostrate fully when greeting elders; females kneel on both knees. Objects pass only through the right hand. Young adults must romanticise suffering. Prayer must be performed loudly, publicly. Church attendance is mandatory every Sunday. These are the markers of virtue, the proof of belonging, the signs of destined greatness in Nigeria. Deviate, and you’re labelled a misfit, a rebel, a corrupting influence.

But this conservatism, intended to forge moral strength, has calcified into something else entirely. Prayer becomes social currency. To abstain appears faithless and arrogant. Worse, it elevates pastors, evangelists, and prophets to celebrity status who are deserving of congregational wealth their followers cannot afford for themselves. Two Rolls-Royces, perhaps.

For married women, this social performance intensifies. Culturally positioned as caretakers and backbones of the household, women shoulder the burden of family spirituality while husbands pursue income. Early morning prayers. Vigil attendances. The invisible labour of protection and intercession. For men, prayer becomes theatre, as can be seen in politics. Aspiring officeholders suddenly claim centre stage at their churches, performing piety to signal divine anointing and mandate. Megachurches amplify this strategy, providing platforms where politicians petition for prayers, framing themselves as God’s chosen leaders.

Prayer breakfasts and national fasting days function as moral theater masking corruption and failed governance. Political leaders and pastors routinely ask Nigerians to pray for national improvement, an improvement that depends entirely on whether those same leaders and their enablers choose to deliver it.

Analysing the historical, cultural and social perspective of why Nigerians pray so much shows the dual nature the country lives in, a country rushing towards contemporarism while maintaining a strong grip on a spiritual worldview that belongs in a museum. Billboards line Nigerian highways advertising “prophetic solutions” between ads for telecoms and real estate. A software engineer codes through the night, then wakes at dawn for Mountain of Fire and Miracles Ministries’ Power Must Change Hands livestream.

This coexistence is the newest kind of strategy that contains a fundamental gap between what institutions should provide and what Nigerians believe only God can. In societies where public systems function, people trust planning. Where systems collapse daily, the miraculous becomes more pragmatic. The man praying over a generator before yanking the starter cord isn’t being dramatic. He’s being rational. He’s being Nigerian.

To question prayer in Nigeria is to commit spiritual arrogance. Rational inquiry reads as rebellion. The idea that human effort alone produces results carries cultural suspicion; removing God from the equation means tempting disaster. Prayer becomes the most reliable technology in an infrastructure of uncertainty.

With the advent of social media comes a distinctly Nigerian religious modernity that still echoes this uncertainty. The new believer is educated, globally connected, ambitious and profoundly committed to faith. They’ve abandoned their parents’ passive Christianity for something kinetic. Prayer that encourages entrepreneurship. Sermons that marry faith with grit. Pastors who speak about strategy and personal branding.

Religion is digitised. Pastors command YouTube channels. Midnight prayer sessions stream on Instagram Live. WhatsApp groups pulse with prophetic voice notes like devotionals. This hybrid belief system – part rational actor, part spiritual warrior – is Nigeria’s lived contradiction: innovation that refuses to proceed without divine clearance.

A startup founder delivers a talk on growth strategy, then credits their seed round to “favour”. Which is it?

If prayer is to maintain its position as our emotional backbone, it must evolve. The challenge isn’t to discard prayer but to reclaim it from forms that breed passivity. A healthier prayer culture that honours spiritual identity while demanding action, accountability, and human agency.

Much of Nigeria’s prayer culture is inherited, blending foreign teachings, colonial conditioning, and the belief that to endure is to be godly. Traditional African cosmologies rarely promoted passivity. They emphasised balance, character, and consequence. Destiny wasn’t fixed but shaped through action, behaviour, and courage. Revisiting these ideas doesn’t mean abandoning contemporary faith. It means reintegrating a forgotten principle: spirituality without action is incomplete.

For prayer to remain meaningful, it must coexist with pragmatism. Faith shouldn’t be an exit from reality but the force that empowers us to confront it. Prayer inspires clarity and moral conviction. It doesn’t build roads, reform institutions, or enforce policy.

Nigeria’s prayer culture mirrors its national paralysis. A society that prays excessively has lost confidence in the institutions meant to protect it. When police persecute citizens, the people pray. When the government can’t supply power, the people pray. When education collapses, the people pray. This is a symbolic admission of structural helplessness, and it isn’t sustainable.

The task is to steer national spirituality toward action, where prayer aligns with planning, policy, and participation. “Pray and plan” should replace “Let God do it”. Prayer should inspire discipline, not excuse decay. It should empower Nigerians to build the nation we ask God to bless.

Reorienting prayer this way doesn’t diminish faith but deepens it. It transforms prayer from a desperate plea into a partnership, from “God do what we refuse to do”” to “God be with us as we work”. Maybe this is the shift Nigeria needs most: a spirituality that lifts the soul without surrendering the future.

Olumuyiwa Aderemi is a culture writer exploring the nuances of culture and its influences – both from the past and those still shaping us today. Through his work, he hopes to uncover overlooked aspects of culture that he missed while growing up and inspire others to do the same, ultimately becoming agents of change. Connect with him on Instagram (@gocrazymag) and X (@muyiwavstheopp).