The question is not whether Nollywood can build a star system. It’s whether it wants to.

By Joseph Jonathan

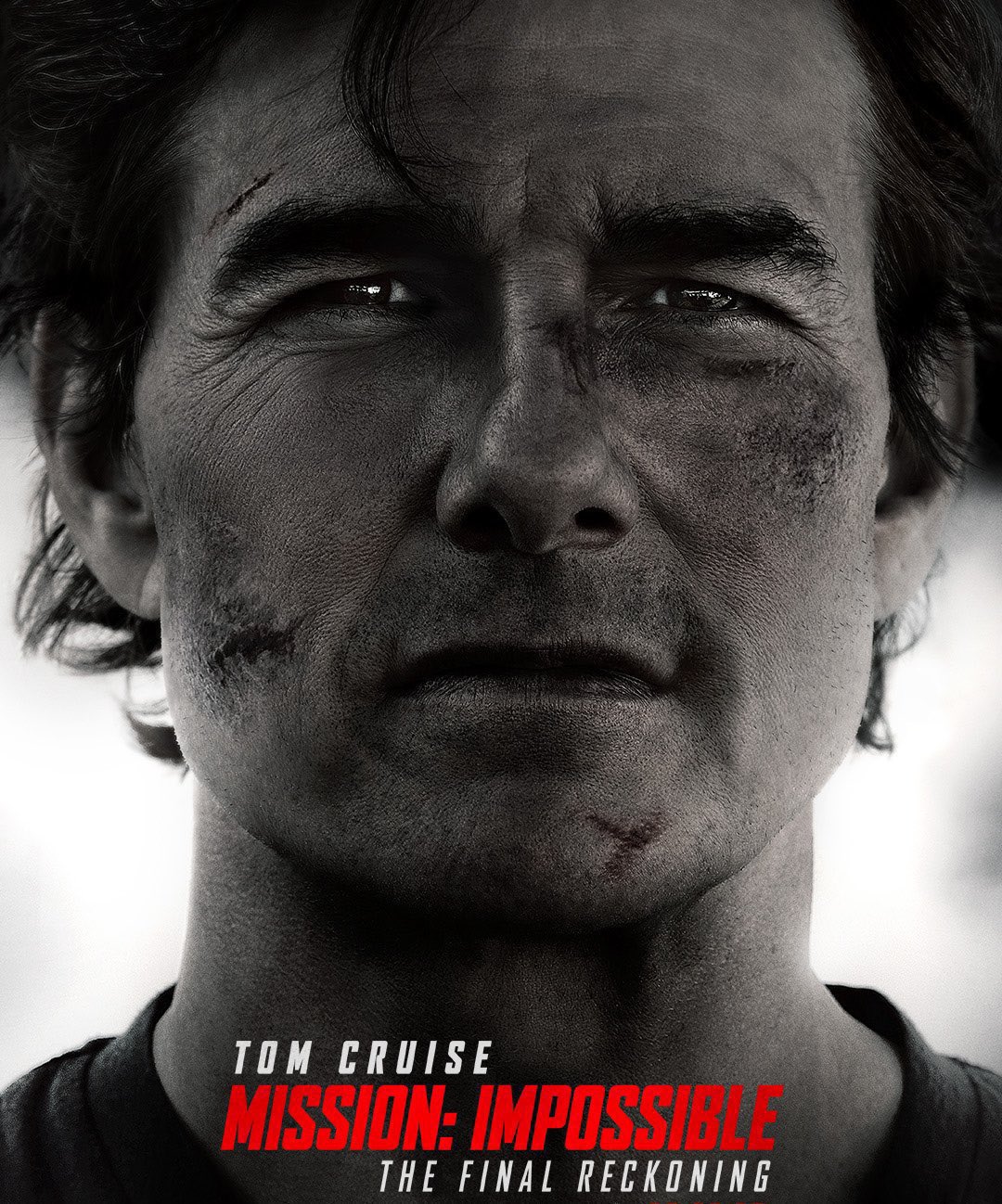

Imagine a Nollywood actor walking into a Lagos mall. They’re swarmed, photographed, asked about their latest endorsement deal, their skincare line, or the last meal they had. The crowd knows their face, their Instagram handle, their brand partnerships. Now imagine Shah Rukh Khan arriving in Mumbai, or Tom Cruise at Cannes. The reaction isn’t just recognition, it’s reverence. Fans don’t ask about endorsements; they recall specific scenes, gestures, the aura accumulated across decades. The difference isn’t fame. It’s myth.

Nollywood produces celebrities and recognisable faces at an industrial scale, but it rarely produces movie stars in the classical sense: figures whose persona alone sells films, structures genres, and accumulates symbolic capital across time. This isn’t a talent deficit. It’s a systemic condition, rooted in how Nollywood is organised, circulated, and culturally imagined. The industry optimises for celebrity circulation, not star accumulation. And the difference matters more than we’ve admitted.

Before we diagnose the problem, we need to define terms. Celebrity and stardom are not synonyms, though Nollywood often treats them as interchangeable. A celebrity is visibility-driven. They have social media presence, brand endorsements, tabloid coverage, and above all, familiarity. They are recognised. But recognition without distance produces accessibility, not aura. Celebrities are known. Stars are imagined.

A movie star is something structurally different. Their persona exists larger than any individual role. When they appear on screen, they bring accumulated associations: gestural signatures, thematic obsessions, a history of choices that feel consistent even when contradictory. Anticipation precedes the film. Narrative expectations are shaped by their presence. The star doesn’t just act in a story; they authorise it. Their face carries symbolic capital built across years, even decades.

Think of Tom Cruise. Before you know the plot of a Cruise film, you know what kind of experience it will be: high-octane, technically obsessive, physically committed. Think of Meryl Streep: you expect intelligence, transformation, a certain moral seriousness even in comedy. Think of Shah Rukh Khan: romantic longing, outsider charm, the myth of the self-made man who never quite belongs. These aren’t just actors playing roles. They are industrial infrastructures. Their names greenlight projects. Their presence shapes marketing. Their absence from a genre becomes newsworthy.

Nollywood has actors everyone knows. But can you name a Nollywood actor whose persona alone sells a film to an audience that knows nothing else about it? Can you name an actor whose thematic preoccupations have shaped how Nollywood writes women, or men, or moral ambiguity? Can you name an actor whose career has been a decades-long conversation with the audience about who they are, what they represent, and what they refuse to be?

The silence that follows those questions is not about talent. It’s about infrastructure.

The Speed Problem

Nollywood’s first structural impediment to stardom is pace. The industry runs on volume. A lead actor might shoot fifteen, twenty, sometimes thirty projects in a single year. They move from set to set, genre to genre, playing a betrayed wife on Monday, a corporate executive on Wednesday, a village priestess on Friday. The roles blur. The characters become interchangeable. The actor is everywhere, and therefore nowhere.

Classical stardom requires temporal gaps. Between films, a space opens—anticipation, speculation, myth-building. What has the star been doing? What will they do next? The absence creates hunger. The return feels like an event. This is why Tom Cruise’s appearance in Top Gun: Maverick (2022) felt like a cultural resurrection. He’d been away, not from public life, but from that persona (Capt. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell) for 36 years. More so, his last film appearance prior to that was in Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018). That gap made the return meaningful.

Nollywood allows no such gaps. An actor finishes one film and immediately begins another. Streaming platforms release their projects simultaneously. A viewer can watch the same actor play six different moral types in a single weekend. Familiarity is produced instantly, but reverence is never allowed to grow. The system mistakes ubiquity for loyalty.

Compare this to Bollywood’s pacing. Shah Rukh Khan, at the height of his powers, rarely released more than two or three films a year (excluding cameos and special appearances as himself). Each release was an occasion. The gap between My Name is Khan (2010) and Jab Tak Hai Jaan (2012) was two years. When he returned in Pathaan (2023) after a four-year hiatus from lead roles, it wasn’t just a comeback, it was a “resurrection”. The absence had done the work. Nollywood actors never disappear long enough for anyone to miss them.

South Korea’s star system engineers scarcity even more aggressively. Lee Min-ho’s career is a study in controlled output. Since his breakout role as Gu Jun-pyo in the acclaimed TV show Boys Over Flowers (2009), Min-ho has been in just 3 feature films and 9 TV shows. In between, there were endorsements, carefully curated public appearances. But never oversaturation. The agencies that manage Korean stars understand what Nollywood’s producer-driven system does not: absence is an investment.

Nollywood’s speed problem isn’t just about quantity. It’s about the collapse of anticipation. If a star is always present, always available, always performing, the audience never develops hunger. And hunger is the precondition for myth.

Producer-Dominated Logic

Nollywood’s second structural problem is who controls the industry. This is not a star system. It’s a producer system. And producer-driven models are fundamentally incompatible with star mythology.

In Nollywood, films are commissioned by producers (individuals or entities) chasing seasonal trends, cultural moments, and distributor demands. The producer is the auteur, the brand, the economic anchor. Actors are hired to execute a vision they rarely shape. Ensemble casts dilute individual presence. The system is designed to survive any actor’s absence. If one lead is unavailable, another is cast. If a star demands too much, a producer builds a project around someone cheaper. The model is economically rational, flexible, and highly productive. It is also hostile to stardom.

Take Behind The Scenes (2025), the highest-grossing Nollywood film to date. It’s a Funke Akindele film, but Akindele’s power comes from owning the means of production, not from star aura in the classical sense. She is a producer-star hybrid, closer to Tyler Perry than to Julia Roberts. The film’s success was built on her brand as a filmmaker, her distribution muscle, and her Christmas slot strategy. Remove her from the film and replace her with another capable actress; does the box office crater? Maybe. But the infrastructure that made the film possible was producer-driven, not star-driven.

Contrast this with Bollywood. Pathaan (2023) was sold as “Shah Rukh Khan is back”. The premise—spy thriller, patriotic action—was secondary. The hook was the star’s return. The film’s existence was justified by Khan’s mythology, not the producer’s vision. Yash Raj Films, the production house, provided infrastructure, but the reason audiences showed up was Khan. The star precedes the script.

Or consider Hollywood. Top Gun: Maverick exists because Tom Cruise willed it into existence. For years, he refused sequels to his iconic films. When he finally greenlit Maverick, it was because he believed he could deliver something worthy of the original. Paramount facilitated, but Cruise authorised. The film’s $1.4 billion global gross was a Tom Cruise event, not a studio product. Nollywood has no equivalent.

Why? Because Nollywood’s producer-dominated model is designed to minimise risk by spreading star labour across multiple projects. A producer who builds a film entirely around one actor’s persona takes on enormous financial exposure. If the star walks, the project collapses. If the star demands backend points, profit margins shrink. If the star’s mythology doesn’t resonate, there’s no fallback. Nollywood’s producers have instead built a system where actors are fungible. This is economically rational. But economic rationality and star-making are often incompatible. The result: Nollywood makes films with stars, not films for stars.

Typecasting Without Iconography

Nollywood has typecasting. It does not have iconography. And the difference is everything.

Typecasting is functional. An actor is repeatedly cast in similar roles because they reliably deliver a tonal or moral effect. The “good woman”. The “bad guy”. The “comic relief”. These are templates, narrative utilities designed to serve plot and theme. The actor becomes recognisable for playing a type, but the type is not imbued with gestural, physical, or thematic singularity. The roles are interchangeable. Another actor could play them with minimal disruption.

Iconography is mythic. It’s the unrepeatable signature: a way of moving, speaking, inhabiting space that becomes inseparable from the star’s persona. Clint Eastwood’s squint, slow-burn rage, and moral pragmatism weren’t just repeated roles; they were a philosophy communicated through gestures. Meryl Streep’s transformative precision, her ability to disappear into characters while somehow remaining unmistakably Streep, is iconographic. Shah Rukh Khan’s outstretched arms, his romantic longing performed with desperate sincerity, is a thematic obsession, not just a casting choice.

Nollywood has actors who play similar roles across films, but the repetition produces familiarity, not myth. Ask yourself: is there a gestural signature, a physicality, a thematic preoccupation that belongs uniquely to any current Nollywood actor? If you say “a Funke Akindele role,” are you describing a persona or a function? If you say “a Jim Iyke role,” are you invoking iconography, or just recalling that he often played the bad boy in 2000s films?

Compare this to Hollywood or Bollywood. A “Denzel Washington role” evokes moral authority, controlled intensity, and a certain kind of masculine dignity. A “Priyanka Chopra role” (in her Bollywood prime) evoked intelligence, sexual agency, and modernity—she played women who wanted things and pursued them unapologetically. A “Meryl Streep role” evokes transformation, yes, but also a particular kind of moral seriousness, even when she’s being funny.

Nollywood’s roles are not built around persona. They are built around moral function. The role dictates the actor, not the reverse. And so the actor never accumulates symbolic capital. They are recognised for being in many films, but not for meaning anything across those films.

Social Media and the Collapse of Distance

Classical stardom required distance. Not physical distance—though that helped—but mythological distance. The space between the star and the audience had to be carefully managed, curated, and protected. The star was seen, but not too much. Interviewed, but not too often. Available, but not accessible. The distance allowed the audience to project, to imagine, to fill the gaps with their own fantasies and interpretations.

Nollywood’s stars have no such distance. They are hyper-visible, relatable, constantly performing authenticity on Instagram Live, TikTok skits, product endorsements, reality TV guest spots. You know what they ate for breakfast. You’ve seen their brand partnerships for everything from hair extensions to betting apps. You’ve watched them beg for votes on Big Brother or dance in viral challenges. They are present; always, exhaustingly, intimately.

This is not inherently the problem. Social media is a tool. The problem is the absence of countervailing structures that might preserve mystery elsewhere. Hollywood stars are also on social media, but they operate within an ecosystem that includes other myth-making apparatuses: Vanity Fair cover profiles that treat them with high-gloss reverence, Oscars machinery that ritualises their cultural value, and controlled late-night talk show appearances that maintain the performance of glamour. The social media presence is one channel among many. The star is also seen in ways that reinforce distance.

Bollywood has similar structures. Karan Johar’s Koffee with Karan is a curated star-making apparatus where celebrities are made to seem accessible, but within a carefully controlled format that reinforces their status. The Filmfare Awards, the IIFA weekend, the brand campaigns shot like high-fashion editorials—all of these are institutions that say: This person is not like you. They are special.

South Korea’s system is even more explicit. Agencies restrict fan access by design, creating scarcity even in the age of ubiquity. A K-drama star’s Instagram might be updated sporadically, with images that feel aspirational rather than relatable. Fan meetings are ticketed, ritualised events. The star is kept distant even when they are present. The agencies understand that accessibility kills aura.

Nollywood has none of these countervailing structures. There are no glossy magazines that treat actors with mythological reverence. There are no institutional gatekeepers curating how stars appear. The few award shows that exist are not treated as sacred cultural rituals; they are often criticised for corruption and irrelevance. Nollywood’s stars are left to self-mythologise, and self-mythologising in real time, on Instagram, is nearly impossible. By the time the star has posted their tenth brand endorsement or their fifteenth “humbled and grateful” acceptance speech, the myth is dead.

What Nollywood lacks is not social media literacy. It lacks institutional myth infrastructure—the press machinery, the archives, the retrospectives, the critical apparatus that says: This career matters. This person is significant. This body of work is worth remembering. Without that, every Nollywood star is left alone with their phone, performing intimacy, killing the distance that might have made them mythic.

Morality, Ambivalence, and the Limits of Myth

Movie stars thrive on contradictions. Not moral simplicity, but unresolved tension. James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955)—alienated, beautiful, doomed—was compelling because the film never fully explained or redeemed him. Marlon Brando’s Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) was sexually magnetic and morally repellent, and the film let both truths coexist. The star becomes mythic not by resolving contradictions, but by embodying them.

Nollywood narratives demand moral clarity. Good is rewarded, evil is punished, ambiguity is temporary and eventually resolved. This is not unique to Nollywood, Bollywood and Hollywood also traffic in moralistic storytelling. But Nollywood’s Pentecostal and conservative gatekeeping structures go further. They demand not just moral resolution in the story, but moral purity in the star.

Bollywood, despite its formulaic morality, allows its stars moments of dangerous ambiguity. Shah Rukh Khan in Darr (1993) plays a psychotic stalker. The film condemns his actions, but it eroticises his obsession, lets the camera linger on his longing, and allows his final confrontation to feel tragic rather than triumphant. The star persona absorbs the contradiction. Khan became more interesting because he could hold both the romantic hero and the unhinged villain in the same body.

Nollywood rarely allows this. Its stars are morally typecast not just in individual films, but across careers. If an actor plays a villain, they are likely to play villains repeatedly, becoming identified with moral failure. If they play virtuous roles, they are expected to remain virtuous on-screen and off. The industry has little tolerance for stars who embody contradiction, who play morally ambiguous characters with empathy, who make audiences want something they should not want.

This is partly a function of audience expectation. Nollywood’s core audience includes religious conservatives who expect films to reinforce moral lessons — it’s the reason why kissing scenes still make Nigerian social media spaces go gaga. Or why audiences condemn (mostly females) actors who show skin.

But it’s also a function of risk aversion. A producer investing in a film does not want to alienate a segment of the audience by making the star too complicated, or too uncomfortable. And so the roles are sanitised. The contradictions are flattened. The star never becomes mythic because they never become dangerous.

Consider Hollywood’s most enduring stars. They are often defined by their moral ambiguity. Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name was not good—he was pragmatic, violent, self-interested. Meryl Streep’s Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada (2006) is monstrous and magnificent. Robert Downey Jr.’s Tony Stark is narcissistic, reckless, and emotionally stunted, and the franchise never fully “fixes” him. These contradictions are not problems. They are the point. The star becomes mythic because they cannot be reduced to a moral lesson.

Nollywood does not permit this. Its stars must be exemplars or cautionary tales. They cannot be both. And so they never accumulate the kind of contradictory, unresolved mythology that makes a star unforgettable.

What Would a Nollywood Star System Require?

This is where the analysis risks becoming wishful thinking. But let’s be realistic. If Nollywood wanted to build a star system—if it decided that cultivating mythological figures was worth the economic tradeoff—what would it require?

First, a provocation: What if Nollywood doesn’t want movie stars?

The producer-driven model is economically rational. Stars are expensive. They’re temperamental. They bottleneck production schedules. They demand creative control and backend points. Nollywood’s flexibility—its ability to churn out 200+ films a year, to respond to trends in real time, to survive any individual actor’s absence—depends on actors being fungible.

The system that produces speed, volume, and flexibility is fundamentally incompatible with the system that produces myth, scarcity, and reverence. So the real question isn’t “How does Nollywood build stars?”; it is, “Would stars even survive Nollywood’s economic logic?”

But let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that some faction within Nollywood—producers, distributors, or even actors themselves—wanted to shift toward a star-driven model. What would that transformation require?

Actors would need to do fewer projects. A star who appears in three carefully chosen films per year allows temporal gaps for anticipation. The audience misses them. Their return feels like an event. This requires paying actors enough per project that they can afford selectivity. Right now, most Nollywood actors take every available job because the per-project fees are low. To enable scarcity, the industry would need to consolidate budgets—fewer films, higher pay per film. This is a structural shift, not an individual choice. The economics must change before the aesthetics can.

Films would need to be built around a star’s established persona or designed to create a new one. This means screenwriters and directors working with the star to develop roles that extend, complicate, or reinterpret their mythology. Hollywood does this constantly. The Mission: Impossible franchise exists as a star vehicle for Tom Cruise’s obsession with practical stunts and physical risk. Erin Brockovich (2000) was tailored to Julia Roberts’ combination of sex appeal and moral seriousness. Nollywood rarely does this. Roles are written generically, then cast. To build stars, the process must reverse: casting creates the role. The star’s persona becomes the starting point, not an afterthought.

Nollywood needs institutions that treat stardom as culturally valuable. This means serious film criticism that analyses actors’ careers as bodies of work, not just individual performances. It means retrospectives and festivals that canonise certain actors, treating them as living archives. It means press machinery that produces long-form profiles, not just Instagram soundbites. It means awards shows that are taken seriously, that function as rituals of cultural validation rather than transactional PR events.

Classical star systems often involve long-term collaborations between directors and actors. Scorsese and De Niro. Tarantino and Samuel L. Jackson. Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. These partnerships build personas over time. Each film is a chapter in an ongoing conversation about who the star is, what they represent.

Nollywood has directors—talented ones—but few sustained partnerships. Biodun Stephen, Kunle Afolayan, and others have worked with actors multiple times, but not in ways that build mythology. For that to happen, the director would need to be seen as an auteur (rare in Nollywood’s producer-driven system), and the star would need to commit to fewer projects so they can sustain such partnerships. A star cannot build mythology with a dozen different directors in a single year. Mythology requires consistency, repetition, and deepening, not variety.

Stars need permission to be complicated. To play morally ambiguous characters. To make audiences uncomfortable. To embody contradictions that are never fully resolved. This requires producers willing to gamble on films that don’t deliver easy moral lessons. It requires audiences willing to engage with complexity. And it requires stars willing to risk their “brand” by playing against type. None of this is easy in an industry where the audience’s moral conservatism is a known commercial factor. But without risk, there is no myth. Safe stars are forgettable stars. The most enduring stars are the ones who made us feel conflicted, not the ones who made us feel righteous.

If Nollywood’s major players—FilmOne, Inkblot, EbonyLife—began functioning like mini-studios rather than project-based producers, they could build multi-year franchises around specific stars. Not just sequels, but universes where the star’s persona is the connective tissue.

Marvel did this with Robert Downey Jr.’s Tony Stark. For a decade, Stark was the anchor of the MCU. The character evolved, but the persona remained consistent. By the time Avengers: Endgame (2019) arrived, audiences were’t just invested in the story—they were invested in Downey’s mythology. Nollywood has nothing equivalent. But it could. Imagine a multi-year franchise built around a single star’s persona, with each instalment deepening the mythology. That would require producers willing to think beyond single-film profitability. It would require stars willing to commit years to a single character. And it would require audiences willing to follow that journey. All of this is possible. None of it is easy.

Patience as Infrastructure

Let’s return to where we began. Nollywood produces celebrities and recognisable faces at an industrial scale. It does not produce movie stars. And now we understand why.

It’s not about talent. It’s about infrastructure. Nollywood’s speed, producer-driven logic, social media saturation, moral conservatism, and lack of institutional myth-making all conspire to prevent the cultivation of stars in the classical sense. The system is optimised for visibility, not reverence. For ubiquity, not mythology. For celebrity, not stardom.

Hollywood, Bollywood, and South Korea did not stumble into stars. They engineered them. They built industries that valued scarcity over volume, persona over function, distance over accessibility. They created institutions—studios, agencies, press machinery, awards rituals—that treated stardom as something worth preserving. They gave their stars time. Time to disappear. Time to return. Time for the audience to miss them, imagine them, mythologise them.

Nollywood has none of this. And so it has no stars, not because it lacks talent, but because it lacks patience. Patience is not passivity. Patience is infrastructure. It’s the willingness to invest in long-term mythology rather than short-term visibility. It’s the discipline to let a star do fewer things so each thing matters more. It’s the courage to protect distance even in an age of total access. It’s the institutional commitment to say: This person is not just another actor. This person is significant. This career is a cultural text we will preserve, interpret, and remember.

Nollywood does not lack stars. It lacks patience. And patience is the hidden infrastructure of stardom. Until Nollywood builds that infrastructure—until it slows down, consolidates power around stars rather than producers, protects mythological distance, and tolerates moral complexity—it will continue producing celebrities everyone knows and movie stars no one remembers.

The question is not whether Nollywood can build a star system. It’s whether it wants to. And whether it’s willing to pay the price: fewer films, higher stakes, longer waits, and the uncomfortable admission that not every actor can be everywhere, all the time. Stardom requires sacrifice. Nollywood has not yet decided if the sacrifice is worth it.

Joseph Jonathan is a historian who seeks to understand how film shapes our cultural identity as a people. He believes that history is more about the future than the past. When he’s not writing about film, you can catch him listening to music or discussing politics. He tweets @Chukwu2big